Lajos Kossuth facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Noble

Lajos Kossuth

de Udvard et Kossuthfalva

|

|

|---|---|

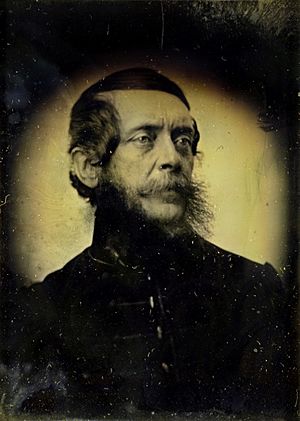

Daguerreotype portrait by Southworth & Hawes, May 1852

|

|

| Governor-President of Hungary | |

| In office 14 April 1849 – 11 August 1849 |

|

| Prime Minister | Bertalan Szemere |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Artúr Görgey (as acting civil and military authority) |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Hungary President of the Committee of National Defence |

|

| In office 2 October 1848 – 1 May 1849 |

|

| Preceded by | Lajos Batthyány (Prime Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Bertalan Szemere (Prime Minister) |

| Minister of Finance of Hungary | |

| In office 7 April 1848 – 12 September 1848 |

|

| Prime Minister | Lajos Batthyány |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Lajos Batthyány |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 September 1802 Monok, Kingdom of Hungary, Habsburg monarchy |

| Died | 20 March 1894 (aged 91) Turin, Kingdom of Italy |

| Resting place | Kerepesi Cemetery |

| Political party | Opposition Party (1847–1848) |

| Spouse | Terézia Meszlényi |

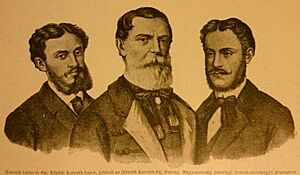

| Children | Ferenc Lajos Ákos Vilma Lajos Tódor Károly |

| Relatives | Juraj Košút (uncle) |

| Signature |  |

Lajos Kossuth (born September 19, 1802 – died March 20, 1894) was a very important Hungarian leader. He was a lawyer, a journalist, and a politician. He became the governor-president of the Kingdom of Hungary during the revolution of 1848–1849.

Kossuth was known for his amazing public speaking skills. He came from a family that wasn't very rich, but his talent helped him become a powerful leader. Many people, even in other countries like Great Britain and the United States, saw him as a freedom fighter. They believed he was a leader for democracy in Europe. There's even a statue of him in the United States Capitol that calls him the "Father of Hungarian Democracy."

Contents

Lajos Kossuth's Early Life

Lajos Kossuth was born in Monok, a small town in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was the oldest of five children in a noble family. His father, László Kossuth, was a lawyer with a small estate. His family had been noble since 1263. Lajos's mother, Karolina Weber, raised her children as strict Lutherans. Because of his family background, Lajos grew up speaking three languages: Hungarian, German, and Slovak.

He went to college in Sátoraljaújhely and Sárospatak, and later to the University of Pest. At 19, he started working in his father's law office. He quickly became a successful lawyer and later a judge and prosecutor. During this time, he also wrote historical notes and translated documents.

Becoming a Politician

In 1832, Kossuth became a deputy for a Hungarian count at the National Diet. This was like a parliament for Hungary. At that time, the Austrian government didn't allow reports from the Diet to be published. Kossuth started writing letters about the meetings, and these letters became very popular. People wanted to know what was happening.

He then started a newspaper called Országgyűlési tudósítások to share these reports. The Austrian government tried to stop him, but people kept sharing his news by hand. Kossuth strongly demanded freedom of the press and speech. Because of this, he was arrested in 1837 and accused of treason.

He spent a year in prison waiting for his trial and was then sentenced to four more years. While in prison, he read a lot and learned English by studying the King James Bible and Shakespeare. This helped him become an even better speaker. His arrest caused a big stir, and the Diet demanded his release. Eventually, he was freed in 1840.

Marriage and Family Life

On the day he was released from prison, Lajos Kossuth married Terézia Meszlényi. She was a strong supporter of his political ideas. Their marriage was unusual because she was Catholic and he was Protestant. At that time, it was rare for people of different religions to marry without one converting. Kossuth refused to convert, and Terézia also refused. This experience made Kossuth a strong supporter of mixed marriages. They had three children: Ferenc Lajos Ákos, Vilma, and Lajos Tódor Károly.

Kossuth as a Journalist and Leader

After his release, Kossuth became a national hero. In 1841, he became the editor of a newspaper called Pesti Hírlap. He wrote about important issues like the economy, social unfairness, and the unequal laws for common people. His articles were very popular, and the newspaper quickly reached a huge number of readers.

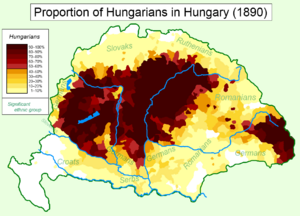

Kossuth believed that everyone born and living in Hungary should be considered "Hungarian," no matter what language they spoke. He wanted Hungarian to be the main language in public life. However, some people disagreed with his ideas, saying he was causing problems between different groups of people in Hungary.

In 1844, Kossuth left Pesti Hírlap. He then worked to make Hungary more independent in its economy and politics. He started a group called "Védegylet" which encouraged people to buy only Hungarian products. He also wanted Hungary to have its own port at Fiume (now Rijeka).

In 1847, Kossuth helped create the Opposition Party. He was elected to the Diet (parliament) for Pest and quickly became the main leader of the opposition.

Kossuth's Role in Government

Minister of Finance

In March 1848, news of a revolution in Paris reached Hungary. Kossuth gave a powerful speech, demanding that Hungary have its own government and that the rest of Austria also have a constitutional government. His speech was so inspiring that it was read in the streets of Vienna, leading to a revolution there.

On March 17, 1848, the Emperor agreed to Hungary's demands. Lajos Batthyány formed the first Hungarian government that was responsible to the elected parliament, not just the King. Kossuth was appointed as the Minister of Finance.

As Minister of Finance, he worked to strengthen Hungary's economy. He created a separate Hungarian currency, and the new banknotes even had his name on them. He also encouraged a strong sense of national pride.

When dangers from other groups and from Vienna grew, Kossuth became even more important. In a speech on July 11, he asked the nation to arm itself for defense and demanded 200,000 soldiers. The people enthusiastically agreed. He traveled around the country, inspiring people to join the army. He helped create the Honvéd (Hungarian army). When Prime Minister Batthyány resigned, Kossuth became the President of the Committee of National Defense.

Regent-President of Hungary

By December 1848, the Hungarian parliament refused to accept the new king, Franz Joseph, because he had not been approved by the Diet. From this point, Lajos Kossuth became the actual leader of Hungary, acting as the elected regent-president.

He had a lot of power and was in charge of the entire government, including the army. Even though he had no military experience, he tried to guide the army's movements. He had some disagreements with General Arthur Görgey, who was a very different person.

Minority Rights

Even though Kossuth mostly spoke to Hungarian nobles, he played a part in creating the first law in Europe that recognized minority rights in 1849. This law allowed minorities to use their own language in local government, courts, schools, and even in their local national guard.

However, Kossuth did not support creating separate regions in Hungary based on nationality. He accepted some demands from Romanians and Croats, but he didn't understand the needs of Slovaks. Even though his father had Slovak origins, Kossuth saw himself as Hungarian and didn't believe in a separate Slovak nation within Hungary. He feared that giving too much freedom to different ethnic groups might break up Hungary.

Russian Intervention and Defeat

During the winter of 1848, Kossuth encouraged the army to fight against the Austrians. After a defeat, he sent General Józef Bem to continue the war in Transylvania.

As the Austrians approached Pest, Kossuth and the government moved to Debrecen. Kossuth took the Crown of St Stephen, a very important symbol of Hungary, with him. In November 1848, Emperor Ferdinand stepped down, and Franz Joseph became the new Emperor. He canceled all the agreements made in March and declared Kossuth and the Hungarian government illegal.

By April 1849, the Hungarians had won many battles. Kossuth then issued the famous Hungarian Declaration of Independence. In it, he declared that the Habsburg family had lost their right to rule Hungary. This was a bold move, but it also caused disagreements among Hungarians. Some wanted only more freedom under the old rulers, while others thought Kossuth wanted to become king himself. This declaration also made it almost impossible to make peace with the Habsburgs.

Kossuth was appointed regent-president to please both those who wanted a king and those who wanted a republic. However, the hopes for success were crushed when Tsar Nicholas I of Russia sent his army to help Austria. All appeals to other European powers failed. On August 11, Kossuth gave up his power to General Görgey, hoping he could save the nation. Görgey then surrendered to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians. Many Hungarian leaders were executed, but Görgey was spared. Kossuth always believed that Görgey was responsible for the defeat.

Life in Exile: Europe and America

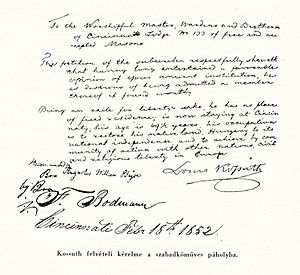

After the revolution, Kossuth became a fugitive and fled to the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman authorities, supported by the British, refused to hand him over to Austria or Russia. He was moved to different places in Turkey. In 1851, the United States Congress invited him to visit. On September 1, 1851, he boarded an American ship, the USS Mississippi, with his family and followers.

He tried to travel through France to England, but the French leader, Louis Napoleon, refused. Kossuth protested, which upset some American officials.

Visit to Great Britain

On October 23, 1851, Kossuth arrived in Southampton, England. He spent three weeks there and was celebrated like a king. Thousands of people greeted him in London, Southampton, and other cities. He gave many speeches in English, which he had learned in prison. His English was described as "wonderfully archaic" and dramatic. He spoke for hours, moving people with his words about the Hungarian cause.

Many British politicians tried to stop the "Kossuth mania," but it was too strong. When a newspaper, The Times, attacked him, copies were burned in public places. His visit even caused political problems for the British government. Kossuth's actions also helped create strong anti-Russian feelings in Britain, which played a part in the Crimean War.

Tour of the United States

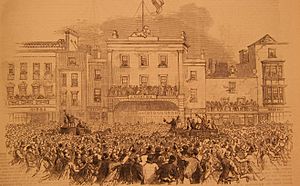

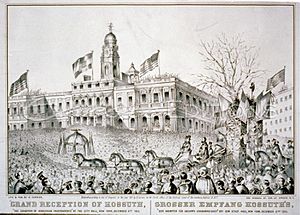

From Britain, Kossuth traveled to the United States. On December 6, 1851, he arrived in New York to a huge welcome, similar to what only George Washington and Marquis de Lafayette had received before. People saw him as a symbol of freedom and democracy.

President Millard Fillmore invited Kossuth to the White House. The US Congress also held a special banquet for him. Kossuth toured many states, giving speeches. In Ohio, he gave a speech that some believe influenced Abraham Lincoln's famous Gettysburg Address. He said, "The spirit of our age is Democracy. All for the people, and all by the people. Nothing about the people without the people - That is Democracy!"

Kossuth's popularity was so great that some babies were even named after him. Many books, poems, and articles were written about him. However, he faced challenges, especially regarding the issue of slavery in America. He tried to avoid taking a side, which upset both those who supported slavery and those who wanted to abolish it. He left the U.S. with less money than he had hoped for.

Later Years in Italy

After his travels, Kossuth lived in London for eight years. He made many important friends in British politics and journalism. He also connected with other exiles from different European countries. He continued to look for ways to free Hungary from Austria. He even tried to organize a Hungarian army during the Crimean War, but it didn't happen.

In 1859, he worked with Napoleon III of France and started to organize a Hungarian army in Italy. But a peace treaty ended these plans. Over time, Kossuth's strong leadership style caused some disagreements among other Hungarian exiles.

Kossuth later moved to Turin, Italy. He was very sad when Ferenc Deák led Hungary to make peace with the Austrian monarchy in 1867. Kossuth wrote an open letter, known as the "Cassandra letter," saying that this agreement would lead to Hungary's downfall. He believed Hungary should be truly independent.

Kossuth never returned to Hungary, even though he was elected to parliament in 1867. He remained a popular figure, but he didn't get involved in politics anymore. In 1879, a law took away citizenship from Hungarians who had been away for ten years. This was a hard blow for him.

In 1890, a recording was made of Lajos Kossuth giving a short speech. This is one of the earliest known sound recordings of a Hungarian speech.

Kossuth's Legacy

Kossuth died in Turin in 1894. His body was brought back to Budapest, where he was buried with great national mourning. A large bronze statue was built in his honor in the Kerepesi Cemetery. He is remembered as a great patriot and speaker.

Many places in Hungary are named after Kossuth, including the main square in Budapest where the Hungarian Parliament Building stands. Most cities in Hungary have streets named after him. Kossuth Rádió, a main radio station, is also named after him.

Even outside Hungary, there are memorials to Kossuth. In Slovakia, a statue of him in Rožňava has been restored twice. In Romania, one statue remains in Salonta. In the United Kingdom, there is a blue plaque on the house where he lived in London, and a street is named after him.

In the United States, Kossuth County, Iowa, is named in his honor, and there are statues and streets named after him in many cities. A bust of Kossuth is displayed in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., alongside busts of other freedom fighters.

Images for kids

-

Kossuth's funeral procession in Budapest in 1894

-

Kossuth statue in Pécs

-

Kossuth Memorial, originally in Budapest, moved to Orczy Park in 2014.

-

Kossuth blue plaque in London, UK

-

Kossuth Road in Cambridge, Canada

-

Kossuth Museum in Kütahya, Turkey

See also

In Spanish: Lajos Kossuth para niños

In Spanish: Lajos Kossuth para niños