Maria Theresa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Maria Theresa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Martin van Meytens, 1759

|

|||||

| Holy Roman Empress | |||||

| Tenure | 13 September 1745 – 18 August 1765 | ||||

| Queen of Bohemia | |||||

| Reign | 12 May 1743 – 29 November 1780 | ||||

| Coronation | 12 May 1743 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles Albert | ||||

| Successor | Joseph II | ||||

| Reign | 20 October 1740 – 19 December 1741 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles II | ||||

| Successor | Charles Albert | ||||

| Archduchess of Austria Queen of Hungary and Croatia Lady of the Netherlands |

|||||

| Reign | 20 October 1740 – 29 November 1780 | ||||

| Coronation | 25 June 1741 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles III | ||||

| Successor | Joseph II | ||||

| Born | 13 May 1717 Vienna, Austria |

||||

| Died | 29 November 1780 (aged 63) Vienna, Austria |

||||

| Burial | Imperial Crypt | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue more... |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Habsburg | ||||

| Father | Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (German: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was a powerful ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1740 until her death in 1780. She was the only woman to rule these lands in her own right. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, and many other territories. Through her marriage, she also became Duchess of Lorraine, Grand Duchess of Tuscany, and Holy Roman Empress.

Maria Theresa began her 40-year reign when her father, Emperor Charles VI, passed away on 20 October 1740. Her father had worked hard to ensure she could inherit his lands. He created a special rule called the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 to allow a woman to inherit. However, he didn't listen to advice to build a strong army and a full treasury. Because of this, he left behind a weak and poor country.

After his death, several countries like Saxony, Prussia, Bavaria, and France went back on their promise to accept Maria Theresa as ruler. Frederick II of Prussia, who became her biggest rival, quickly invaded and took the rich province of Silesia. This led to the War of the Austrian Succession, which lasted eight years. Despite the difficult situation, Maria Theresa gained important support from the Hungarians. She successfully defended most of her lands, losing only Silesia and a few small areas in Italy. Later, she tried to get Silesia back during the Seven Years' War, but she was not successful.

Even though her husband, Emperor Francis I, and her oldest son, Emperor Joseph II, were officially co-rulers, Maria Theresa was the true leader. She made all the important decisions with the help of her advisors. She introduced many important changes in government, money, medicine, and education. She also encouraged commerce (trade) and farming, and made Austria's army much stronger. These changes helped Austria become a more powerful country in Europe.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Maria Theresa was born on 13 May 1717 in Vienna. She was the second child of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Her older brother had died a year before she was born, making her the oldest surviving child. Her birth was a bit of a disappointment to her father, who had hoped for a son to continue his family line.

From the moment she was born, Maria Theresa was the next in line to rule the Habsburg lands. Her father had created the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 to make sure his own daughters would inherit before his nieces. He worked hard to get other European countries to agree to this rule. Many countries, including Great Britain and France, recognized the sanction. However, some of them, like France and Prussia, later broke their promises.

Maria Theresa had two younger sisters, Maria Anna and Maria Amalia. Portraits show that Maria Theresa looked like her mother and Maria Anna. She had large blue eyes, light hair with a hint of red, and a strong build.

Maria Theresa was a serious and quiet child. She loved singing and archery. Her father didn't let her ride horses, but she learned later for her Hungarian coronation. She also enjoyed participating in operas that her family put on. Jesuits taught her, and she was good at Latin. However, she didn't learn much else from them. She spoke Viennese German, which was unusual for a royal. She had a close relationship with her governess, Countess Marie Karoline von Fuchs-Mollard, who taught her manners. Her education focused on skills like drawing, painting, music, and dancing, which were important for a future queen. Her father allowed her to attend council meetings from age 14, but he never talked about state matters with her. He didn't really prepare her to be a ruler.

Marriage and Family Life

Maria Theresa's marriage was planned when she was very young. She was first considered for Leopold Clement of Lorraine, but he died. His younger brother, Francis Stephen, then came to Vienna. Maria Theresa liked Francis Stephen a lot.

Even though Francis Stephen was her father's favorite choice, the Emperor looked at other options. He couldn't arrange a marriage to the Protestant prince Frederick of Prussia because of religious differences. In 1725, he planned for Maria Theresa to marry Charles of Spain. But other European countries made him cancel this plan. Maria Theresa was happy about this, as she had grown close to Francis Stephen.

Francis Stephen stayed at the imperial court until 1729. He became the Duke of Lorraine. They were officially engaged on 31 January 1736, during the War of the Polish Succession. Louis XV of France wanted Francis Stephen to give up his home duchy of Lorraine. In return, Francis Stephen would receive the Grand Duchy of Tuscany when its childless ruler died. Maria Theresa's father insisted on this deal. The couple married on 12 February 1736.

Maria Theresa loved her husband very much. Her letters to him before their wedding showed how eager she was to see him. After the Duke of Tuscany died in 1737, Francis Stephen became Grand Duke of Tuscany. However, their stay in Florence was short because Maria Theresa's father worried he might die while she was far away.

Raising Many Children

Maria Theresa had sixteen children over twenty years. Thirteen of them lived past infancy. Her first child, Maria Elisabeth, was born less than a year after her wedding. The birth of a girl was a disappointment, as were the births of her next two daughters. While fighting to keep her lands, Maria Theresa gave birth to her first son, Joseph. She named him after Saint Joseph, to whom she had prayed for a male child.

Her favorite child, Maria Christina, was born on Maria Theresa's 25th birthday. Five more children were born during the war. Maria Theresa was always busy with pregnancies or new babies, even during wartime. She had her last child, Maximilian Francis, at age 39. She once said that if she hadn't been pregnant so often, she would have gone into battle herself.

Dealing with Illness and Loss

Four of Maria Theresa's children died before they became teenagers. Her oldest daughter, Maria Elisabeth, died at three. Her third child, Maria Carolina, died shortly after her first birthday.

Smallpox was a constant danger to the royal family. In 1761, it killed her second son, Charles, at age fifteen. In 1762, her twelve-year-old daughter Johanna also died from the disease. In 1763, Joseph's first wife, Isabella, died from smallpox. Joseph's second wife, Maria Josepha, also caught the disease in 1767 and died a week later. Maria Theresa didn't care about the risk and hugged her daughter-in-law before the sickroom was closed off.

Maria Theresa herself caught smallpox from her daughter-in-law. People across Vienna prayed for her recovery. Joseph stayed by her bedside. On 1 June, she was given the last rites. When news came that she had survived, there was great joy.

In October 1767, her fifteen-year-old daughter Josepha also showed signs of smallpox. It was thought she got it after visiting the tomb of Joseph's wife. Josepha died quickly. Maria Theresa blamed herself for her daughter's death for the rest of her life. The last in the family to get sick was Elisabeth. She recovered but was badly scarred. Because of these losses, Maria Theresa strongly supported inoculation (an early form of vaccination) and insisted her family members get it.

Arranging Royal Marriages

Maria Theresa had to arrange marriages for her older children. She used these marriages to help her country's power and influence. She loved her children but often put the needs of the state first. She wrote to all her children at least once a week and felt she had the right to guide them, no matter their age or rank.

In 1770, her youngest daughter, Maria Antonia, married Louis, the future King of France. Maria Antonia became Marie Antoinette. Maria Theresa made sure her daughter learned about the French court. She wrote to Marie Antoinette often, sometimes scolding her for being lazy or not having children yet.

Maria Theresa was strict with most of her children. She criticized Leopold for being too quiet and Maria Carolina for her political actions. The only child she didn't often scold was Maria Christina, who had her mother's full trust. Maria Theresa wanted many grandchildren, but she had only about two dozen when she died.

Becoming a Ruler

Charles VI died on 20 October 1740. He had ignored advice to build up the army and treasury. Austria was left poor and weak from recent wars. Maria Theresa found herself in a tough spot. She didn't know much about running the country and didn't realize how weak her father's advisors were. She decided to keep his advisors and let her husband, Francis Stephen, handle some matters. Both decisions later caused problems.

Maria Theresa later wrote about how she became ruler: "I found myself without money, without credit, without army, without experience and knowledge... and finally, also without any counsel."

She quickly worked to make her husband, Francis Stephen, the Holy Roman Emperor. A woman could not be elected empress. To make him eligible, Maria Theresa made Francis Stephen a co-ruler of Austria and Bohemia on 21 November 1740. Even though she loved him, Maria Theresa never let her husband make state decisions and often sent him out of meetings if they disagreed.

The first public show of her power was when the Lower Austrian nobles formally accepted her as their ruler on 22 November 1740. This event showed everyone that she was the rightful queen.

Wars and Challenges

War of the Austrian Succession

Right after Maria Theresa became ruler, several European leaders who had promised to support her broke their word. Queen Elisabeth of Spain and Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria wanted parts of her lands.

In December, Frederick II of Prussia invaded Silesia. He demanded Maria Theresa give it to him. She refused, deciding to fight for the rich province. Frederick offered a deal: he would support her if she gave him some of Silesia. Her husband thought this was a good idea, but Maria Theresa and her advisors disagreed. They feared that giving up any land would make her claim to all her lands weaker. Maria Theresa was determined to keep "the jewel of the House of Austria." This started the First Silesian War. Maria Theresa always called Frederick "that evil man."

Austria's army was not ready for war. They suffered a big defeat in April 1741. France then planned to divide Austria among Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Spain. Vienna was in a panic. Maria Theresa reluctantly agreed to talk about peace.

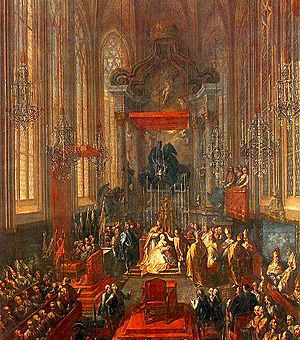

Against all odds, the young Queen gained strong support from Hungary. She was crowned Queen of Hungary in Pressburg on 25 June 1741. She had practiced horse riding for months for the ceremony. To please those who thought a woman couldn't rule, Maria Theresa used male titles, calling herself "archduke" and "king."

By July, peace talks failed. Maria Theresa needed troops from Hungary. On 11 September 1741, she appeared before the Hungarian Diet (assembly) wearing the crown of St. Stephen. She spoke in Latin, saying that the very existence of Hungary, herself, and her children was at stake. She dramatically held her baby son and heir, Joseph, and cried, asking the "brave Hungarians" to defend him. This act won their sympathy, and they declared they would die for her.

In 1741, Maria Theresa learned that the people of Bohemia preferred Charles Albert of Bavaria as their ruler. Maria Theresa, pregnant and desperate, vowed to defend her kingdom. On 26 October, Charles Albert captured Prague and declared himself King of Bohemia. Maria Theresa cried when she heard this. Charles Albert was elected Holy Roman Emperor in January 1742, the first non-Habsburg since 1440. The same day, Austrian troops captured Munich, Charles Albert's capital.

The Treaty of Breslau in June 1742 ended the fighting between Austria and Prussia. Maria Theresa then focused on getting Bohemia back. French troops left Bohemia that winter. On 12 May 1743, Maria Theresa was crowned Queen of Bohemia.

Prussia worried about Austria's gains. Frederick again invaded Bohemia, starting the Second Silesian War in 1744. French plans failed when Charles Albert died in January 1745. Francis Stephen was elected Holy Roman Emperor on 13 September 1745. Maria Theresa again accepted the loss of Silesia in December 1745. The larger war continued for three more years. The Treaty of Aachen ended the war, confirming Prussia's control of Silesia. Maria Theresa gave the Duchy of Parma to Philip of Spain. France had taken the Austrian Netherlands but returned them to Maria Theresa to avoid future wars.

The Seven Years' War

Frederick of Prussia's invasion of Saxony in August 1756 started the Third Silesian War and the larger Seven Years' War. Maria Theresa and her advisor Kaunitz wanted to get Silesia back. Kaunitz had worked to gain France's support. The British refused to help Maria Theresa get Silesia back, and Frederick II made a deal with them.

Maria Theresa then sent Georg Adam, Prince of Starhemberg to make a deal with France. This led to the First Treaty of Versailles in May 1756. Before this, France was Austria's enemy. Now, they were united against Prussia. This change in alliances was called the Diplomatic Revolution.

In May 1757, the Second Treaty of Versailles was signed. France promised to send 130,000 men and 12 million florins each year to Austria. They would fight until Prussia gave up Silesia. In return, Austria would give some towns in the Austrian Netherlands to the son-in-law of Louis XV.

Austrian troops fought bravely. The Battle of Kolín in 1757 was a big victory for Austria. Frederick lost many troops. Prussia was also defeated in other battles. Austrian and Russian troops even occupied Berlin for a few days in 1760. However, these wins did not help Austria win the war. Maria Theresa realized she couldn't get Silesia back without Russia's help, which ended when Tsaritsa Elizabeth died in 1762. France also reduced its financial help.

The war ended with the Treaty of Hubertusburg and Paris in 1763. Silesia remained with Prussia. However, a new balance of power was created in Europe, and Austria's position was stronger due to its alliances. Maria Theresa decided to focus on improving her own country and stopped fighting wars.

Reforms and Changes

Maria Theresa was traditional in her beliefs, but she made big changes to make Austria's army and government more efficient. She hired Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz, who created a standing army of 108,000 men. The government paid for the army by taxing the nobility, who had never paid taxes before. Haugwitz also centralized government offices, creating a class of about 10,000 government officials by 1760. However, some areas like Hungary were not affected by these changes, as Maria Theresa had promised to respect their special rights.

After failing to get Silesia back, the government was reformed again. In 1761, the main government office became the United Austrian and Bohemian Chancellery, with separate courts and financial groups. She also created a Council of State in 1760, made up of experienced advisors. This showed that Maria Theresa was not a ruler who did everything herself, unlike Frederick II of Prussia.

Maria Theresa doubled the government's income from 20 to 40 million florins between 1754 and 1764. Her financial changes greatly improved the economy. By 1775, the Habsburg monarchy had its first balanced budget. By 1780, the government's income reached 50 million florins.

Improving Medicine

Maria Theresa brought Gerard van Swieten from the Netherlands to improve medicine. He helped create the Viennese Medicine School. Maria Theresa also made rules about burials to improve hygiene.

After the smallpox outbreak in 1767, she promoted inoculation. She learned about it from other royals. Despite some doubts, she ordered trials on orphans, which were successful. She then ordered an inoculation center to be built and had herself and two of her children inoculated. She even hosted a dinner for the first 65 inoculated children at Schönbrunn Palace, serving them herself. Maria Theresa helped change doctors' negative views on inoculation in Austria.

In 1770, she made strict rules for selling poisons. In 1773, she banned the use of lead in eating or drinking containers, allowing only pure tin.

Law and Justice

To unite the Habsburg lands, Maria Theresa needed one legal system. She gathered all the different laws into a document called the Codex Theresianus. In 1769, she published the Constitutio Criminalis Theresiana, a criminal law code. This code still allowed torture to get the truth and made witchcraft a crime. This law was used in Austria and Bohemia but not in Hungary.

Maria Theresa is credited with ending witch hunts in Zagreb. She stepped in to help Magda Logomer, who was the last person accused of witchcraft there.

In 1776, Austria outlawed torture, mainly because her son Joseph II pushed for it. Maria Theresa, influenced by older traditions, was against ending torture at first. She found it hard to fully accept the new ideas of the Enlightenment. However, she did create the Supreme Judiciary in 1749, which was the highest court for all her lands.

Education for All

Maria Theresa made education a top priority throughout her reign. At first, she focused on wealthier classes. She allowed non-Catholics to attend university and introduced subjects like law, reducing the focus on theology. She also created schools to train government officials and diplomats.

In the 1770s, she reformed the school system for everyone. This was one of her most successful changes. A census in 1770–1771 showed that many people couldn't read or write. Maria Theresa asked a school reformer from Silesia, Johann Ignaz von Felbiger, to come to Austria. His ideas became law in 1774. Maria Theresa's reforms were based on Enlightenment ideas, but they also aimed to create better administrators and specialists for the state.

Her reforms created public primary schools that children aged six to twelve, both boys and girls, had to attend. The lessons focused on being responsible, disciplined, and using reason, not just memorizing facts. Education was multilingual, starting in the child's native language and then moving to German. Teachers' pay and status were improved, and training colleges were set up.

Many people opposed these changes. Some peasants wanted their children to work in the fields. Maria Theresa arrested those who strongly resisted. Many nobles also opposed the reforms, fearing they would lose power or that more education would spread new ideas. But Maria Theresa and her minister Franz Sales Greiner pushed the reforms through. School attendance greatly increased, especially in Vienna.

Economy and Peasant Life

Maria Theresa wanted to improve people's lives and living standards. She saw that happier, more productive peasants meant more income for the state. Her government also tried to strengthen industries by offering help and setting up trade barriers. After losing Silesia, she encouraged textile industries to move to northern Bohemia. She also reduced or removed internal trade taxes.

Later in her reign, Maria Theresa reformed the system of serfdom, which was how farming worked in many eastern parts of her lands. Peasants were forced to work for landlords. A census in 1770–1771 showed how poor peasants were because of the extreme demands for forced labor, called "robota." Some landlords made peasants work up to seven days a week on their land, leaving peasants only nights to work their own fields.

A severe famine in the early 1770s also pushed her to make changes. Maria Theresa was influenced by reformers who wanted big changes to the serf system so peasants could make a living. From 1771 to 1778, she issued "Robot Patents" (rules about forced labor) that limited peasant labor in German and Bohemian areas. The goal was to ensure peasants could support themselves and their families.

By 1772, Maria Theresa wanted more radical changes. In 1773, she put her minister Franz Anton von Raab in charge of a project on royal lands in Bohemia. He divided large estates into small farms, changed forced labor into leases, and allowed farmers to pass these leases to their children. This program, called Raabisation, was very successful. Maria Theresa then had it used on former Jesuit lands and other royal lands.

However, nobles strongly resisted Maria Theresa's attempts to extend this system to their large estates. They argued that the crown had no right to interfere. Surprisingly, her son Joseph II, who had earlier wanted to abolish serfdom, supported the nobles. He worried that landlords would lose too much income. Maria Theresa was unable to fully carry out her planned reform. Serfdom was only abolished after her death by Joseph II.

Later Years and Legacy

Emperor Francis, Maria Theresa's beloved husband, died on 18 August 1765. Maria Theresa was heartbroken. She stopped wearing bright clothes, cut her hair short, painted her rooms black, and wore mourning clothes for the rest of her life. She avoided court events and theater. Every August and on the 18th of each month, she spent the day alone. She said she felt like "an animal with no true life or reasoning power."

Her oldest son, Joseph, became Holy Roman Emperor. Maria Theresa made him her new co-ruler on 17 September 1765. From then on, mother and son often disagreed on how to rule. Joseph inherited a lot of money from his father, which went into the treasury. Maria Theresa gave Joseph full control over the military.

Maria Theresa was a very capable ruler. She had a warm heart, a practical mind, and strong determination. She was also willing to listen to her advisors, even if their ideas were different from her own. Joseph, however, found it harder to work with the same advisors.

Their relationship was complicated. Maria Theresa often admired Joseph's talents but also scolded him. She sometimes complained that he avoided her and that she was a "burden." She thought about giving up her throne but decided not to. Joseph often threatened to resign as co-ruler, but he also stayed. Maria Theresa believed her recovery from smallpox in 1767 was a sign that God wanted her to rule until she died.

Joseph and Prince Kaunitz arranged the First Partition of Poland despite Maria Theresa's objections. She felt it was wrong to take land from an innocent nation. But Joseph and Kaunitz argued it was too late to stop, and Maria Theresa agreed when she realized Prussia and Russia would do it with or without Austria. Austria gained Galicia and Lodomeria. Frederick of Prussia joked that "the more she cried, the more she took."

A few years later, Russia defeated the Ottoman Empire. In 1775, the Ottoman Empire gave the area of Bukovina to Austria. In 1777, the Elector of Bavaria died without children. Joseph tried to trade Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands. This worried Frederick II of Prussia, leading to the War of Bavarian Succession in 1778. Maria Theresa reluctantly agreed to occupy Bavaria. A year later, she made peace with Frederick II despite Joseph's objections. Austria gained the Innviertel area, but the war cost a lot of money.

Maria Theresa likely never fully recovered from her smallpox attack in 1767. She suffered from breathing problems, tiredness, coughing, and trouble sleeping. She also developed swelling.

Maria Theresa became very ill on 24 November 1780. On 28 November, her doctor told her it was time. She died on 29 November, surrounded by her children. She is buried in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna next to her husband in a coffin she had prepared.

Her old rival, Frederick the Great, said that she had honored her throne and her gender. Even though he fought her in three wars, he never saw her as an enemy. With her death, the House of Habsburg family line ended and was replaced by the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. Joseph II became the sole ruler and made many quick changes. Maria Theresa issued about 100 new rules each year, while Joseph issued almost 700!

Maria Theresa was very good at connecting with her people. She made them respect and like her. Her 40-year reign was very successful compared to other Habsburg rulers. Her reforms turned the empire into a modern state with a strong international standing. Her rule is seen as the start of "enlightened absolutism" in Austria, where rulers focused on the well-being of the state and its people. Even though some of her policies were not fully in line with the Enlightenment ideas (like her support for torture), her reforms were mostly centralizing and absolutist.

Memorials and Honors

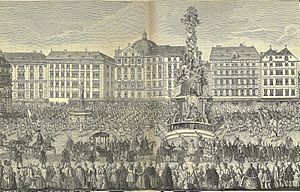

Many streets and squares were named after Maria Theresa throughout the empire. Statues and monuments were also built in her honor. A large bronze monument was built in Vienna's Maria-Theresien-Platz in 1888. The Maria Theresia Garden Square (Uzhhorod) was built in her memory in 2013.

Several of her descendants were named after her, including her granddaughter Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily, who also became Holy Roman Empress.

- The Imperial and Royal Navy ship SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia was built in 1891.

- The Military Order of Maria Theresa was founded by her in 1757.

- The Theresianum school was founded by her in 1746 and is one of Austria's best schools.

- The Maria Theresa thaler coin was first made during her reign and is still produced today.

- Asteroid 295 Theresia was named in her honor in 1890.

- The garrison town of Terezin (Theresienstadt) in Bohemia was built in 1780 and named after her.

- A type of crystal chandelier is known as the Marie Therese chandelier.

- The Maria Theresa Room in the Hofburg palace in Vienna is named after her. New Austrian governments take their oath of allegiance in this room.

- The Maria Theresa Room is also the most elegant room in the Sándor Palace, Budapest, the official residence of the president of Hungary.

In Media

Maria Theresa has been featured in films and TV series. These include the 1951 film Maria Theresa and the 2017 Austrian-Czech miniseries Maria Theresia. In the 2006 film Marie Antoinette, Marianne Faithfull played Maria Theresa.

Images for kids

-

Maria Theresa and her family celebrating Saint Nicholas, by Archduchess Maria Christina, in 1762

-

Hungarian President László Sólyom with U.S. President George W. Bush in the Maria Theresa Room of Sándor Palace (2006)

See also

In Spanish: María Teresa I de Austria para niños

In Spanish: María Teresa I de Austria para niños