Partitions of Poland facts for kids

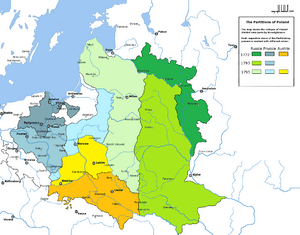

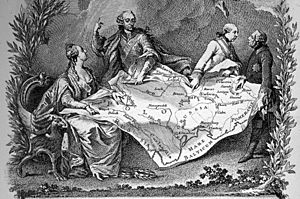

The Partitions of Poland are a big event in history. They describe a time when the independent country called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was divided up. Its powerful neighbors, Prussia, Imperial Russia, and the Habsburg Monarchy, took parts of its land.

There were three main partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth:

- The First Partition: August 5, 1772

- The Second Partition: January 23, 1793 (Austria did not take part in this one)

- The Third Partition: October 24, 1795

These events happened in the second half of the 18th century. They led to the end of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as an independent country. Sometimes, people also talk about a "Fourth Partition of Poland." This term refers to later divisions of Polish lands, like after the Napoleonic era in 1815, or in 1939 when Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Contents

How Poland Was Divided

Before the Divisions Began

For a long time, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had a special rule called the liberum veto. This rule meant that any member of the parliament (called the Sejm) could stop a new law. This made it very hard for Poland to make important decisions or change its laws.

By the mid-1700s, Poland was not fully independent. It was almost like a vassal state, meaning it was controlled by Russia. Russian rulers often chose who would be the Polish king. The last Polish king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, was even a close friend of the Russian Empress Catherine the Great.

Around 1730, Poland's neighbors – Prussia, Austria, and Russia – made a secret deal. They wanted to keep Poland weak and prevent it from changing its laws. This secret group was known as the "Alliance of the Three Black Eagles." All three countries used a black eagle as their symbol, unlike Poland's white eagle. Poland had to rely on Russia for protection, especially against the growing power of Prussia.

During the Seven Years' War, Poland stayed neutral. But it let Russian troops use its land to fight against Prussia. In return, Frederick II of Prussia ordered fake Polish money to be made. This caused big problems for Poland's economy.

Empress Catherine the Great of Russia used her power over Polish nobles. She forced Poland to accept a new constitution in 1767. This constitution was called the Repnin Sejm. It brought back the liberum veto and other old rules that kept Poland weak. Russia also demanded religious freedom for Protestants and Orthodox Christians in Poland. This angered many Polish Catholics and led to a war.

The Poles tried to fight back against foreign control in an uprising called the Bar Confederation (1768–1772). But their forces were not strong enough to beat the regular Russian army. There was also a peasant uprising in Ukraine, which added to the chaos.

The First Division (1772)

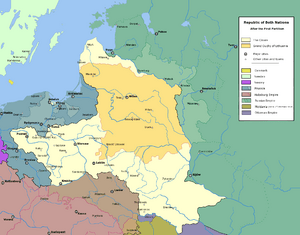

On February 19, 1772, Prussia, Russia, and Austria signed an agreement in Vienna. They decided to divide parts of Poland. In August, their armies marched into Poland and took over the agreed-upon areas. On August 5, 1772, they officially announced their takeover. Poland was too tired from the previous fighting to resist much.

Even though Poland was weak, some Polish forces kept fighting. Fortresses like Tyniec and Częstochowa held out for a long time. But eventually, they fell. The city of Kraków was captured by Russian general Alexander Suvorov.

The three countries officially approved the division on September 22, 1772.

- Frederick II of Prussia was very happy. He took good care of his new Polish subjects. He even made it a rule for Prussian princes to learn Polish.

- Kaunitz of Austria was proud of getting rich salt mines in Bochnia and Wieliczka.

- Catherine of Russia was also very pleased.

After this first division, Russia gained parts of Livonia and Belarus. Prussia took areas like Ermland and parts of Greater Poland. Austria received parts of Little Poland and all of Galicia.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth lost about 30% of its land. This was about 484,000 square kilometers, with four million people. Austria gained the most people and income from this division.

After taking their new lands, the three powers demanded that King Stanisław and the Polish parliament (Sejm) approve their actions. The King asked other European countries for help, but none came. The armies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria then occupied Warsaw. They forced the Polish parliament to meet and agree to the division. Any senators who spoke against it were arrested and sent away to Siberia by Russia.

By taking northwestern Poland, Prussia gained control over 80% of Poland's foreign trade. Prussia also charged very high taxes on goods, which made Poland's economy even weaker.

The Second Division (1793)

By 1790, Poland was in a very weak state. It was forced to make an alliance with its enemy, Prussia. This alliance, called the Polish-Prussian Pact of 1790, made the next divisions almost certain.

In 1791, Poland tried to reform itself with a new law called the May Constitution. This constitution gave more rights to regular citizens and separated the government into three parts. It also tried to fix the problems caused by the old rules. These changes worried Poland's neighbors. They feared Poland might become strong again.

Empress Catherine of Russia was angry. She claimed Poland was becoming too much like revolutionary France. So, Russian forces invaded Poland in 1792.

In the Polish-Russian War of 1792, some conservative Polish nobles, known as the Targowica Confederation, fought against the new constitution. They believed Russia would help them bring back the old ways. Poland's Prussian allies abandoned them. The Polish forces supporting the constitution were defeated by the Targowica group and the Russian army.

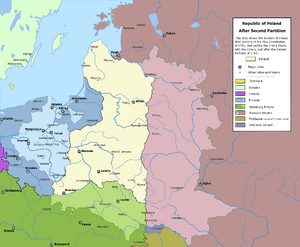

Prussia then signed a new treaty with Russia. They agreed to undo Poland's reforms and take more Polish land. In 1793, the last Polish parliament, the Grodno Sejm, met. With Russian soldiers watching, the members had to agree to Russia's demands. In this second division, Russia and Prussia took so much land that only one-third of Poland's 1772 population remained in the country.

The Targowica confederates and King Stanisław lost a lot of support. Many Poles now supported the reformers. This led to the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794.

The Third Division (1795)

The Polish uprising, led by Tadeusz Kościuszko, had some early victories. But his forces were eventually defeated by the stronger Russian army. The countries that had been dividing Poland saw the growing unrest. They decided to solve the "Polish problem" by completely removing Poland from the map.

On October 24, 1795, representatives from Russia, Prussia, and Austria signed a treaty. They divided the remaining parts of Poland among themselves.

- Russia took about 120,000 square kilometers and 1.2 million people, including the city of Wilno.

- Prussia took about 55,000 square kilometers and 1 million people, including Warsaw.

- Austria took about 47,000 square kilometers and 1.2 million people, including Lublin and Kraków.

What Happened Next

After these divisions, Poland no longer existed as an independent country. Later, Napoleon created a small Polish state called the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. But after Napoleon's defeat, things got even worse for Poles. Russia gained even more Polish land. After a Polish uprising in 1831, Russia took away Poland's self-rule. Poles faced losing their property, being sent away, forced military service, and their universities were closed.

Because of the Partitions, Poles had to fight for their freedom. Many Polish poets, politicians, and artists were forced to leave their homeland. They became revolutionaries in the 1800s. The desire for freedom became a key part of Polish romanticism. Polish revolutionaries fought alongside Napoleon and took part in other uprisings across Europe, like the Spring of Nations.

The "Fourth Partition"

The term "Fourth Partition of Poland" is sometimes used for later divisions of Polish lands. These include:

- The division of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna.

- When "Congress Poland" became part of Russia in 1832.

- When the Free City of Kraków became part of Austria in 1846.

- The division of Poland between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Particiones de Polonia para niños

In Spanish: Particiones de Polonia para niños