Lev Shestov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

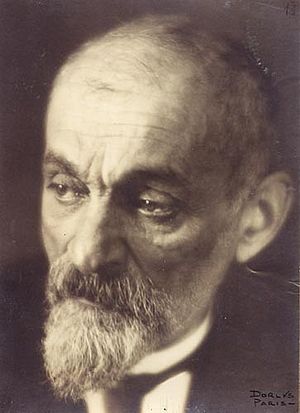

Lev Shestov

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | January 31, 1866 |

| Died | November 19, 1938 (aged 72) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy Western philosophy |

| School | Christian existentialism |

|

Main interests

|

Theology, nihilism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Philosophy of despair |

|

Influences

|

|

Lev Isaakovich Shestov (born Yehuda Leib Shvartsman; 31 January 1866 – 19 November 1938) was a Russian existentialist and religious philosopher. He is famous for questioning traditional rationalism and positivism in philosophy.

Shestov believed that pure reason and metaphysics (the study of basic reality) could not fully explain deep truths. These truths include the nature of God or why we exist. Some experts even call his work "anti-philosophy" because it challenged common ways of thinking.

He wrote a lot about other thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Søren Kierkegaard. He also studied Russian writers such as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Anton Chekhov. His well-known books include Apotheosis of Groundlessness (1905) and his most important work, Athens and Jerusalem (1930-37). After moving to France in 1921, he became friends with and influenced many important thinkers. He lived in Paris until he passed away in 1938.

Contents

Lev Shestov's Early Life

Lev Isaakovich Schwarzmann was born in Kiev, which was then part of the Russian Empire. His family was Jewish. He was a cousin of Nicholas Pritzker, a lawyer who moved to Chicago and started the well-known Pritzker family.

Lev Shestov had a challenging education because he often disagreed with authority figures. He studied law and mathematics at Moscow State University. However, after a disagreement with a student inspector, he had to return to Kiev to finish his studies.

His final paper for his law degree was rejected by the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. This happened because his ideas were seen as too revolutionary. This meant he could not become a doctor of law.

Developing His Ideas

In 1898, Shestov joined a group of important Russian thinkers and artists. This group included Nikolai Berdyaev and Sergei Diaghilev. Shestov wrote articles for their journal. During this time, he finished his first major philosophy book. It was called Good in the Teaching of Tolstoy and Nietzsche: Philosophy and Preaching. Both Tolstoy and Nietzsche greatly influenced Shestov's thoughts.

He continued to develop his ideas in a second book about Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche. This book made Shestov known as an original and sharp thinker.

The Idea That "Everything Is Possible"

In his 1905 book, All Things Are Possible (also called Apotheosis of Groundlessness), Shestov used a style similar to Nietzsche's, writing in short, powerful statements. He explored the differences between Russian and European literature.

This book is a deep look into existentialist philosophy. It questions and even makes fun of our basic attitudes toward life. The writer D.H. Lawrence summarized Shestov's main idea as: " 'Everything is possible' - this is his really central cry." Lawrence explained that this isn't about believing in nothing. Instead, it's about freeing the human mind from old rules. The main positive idea is that our inner self, or soul, truly believes in itself and nothing else.

Shestov discussed important topics like religion, reason, and science in this book. He explored these ideas further in later works, such as In Job's Balances. A key quote from All Things Are Possible is: "...we need to think that only one assertion has or can have any objective reality: that nothing on earth is impossible." He believed we should always resist anyone who tries to limit our understanding with fixed truths.

Not everyone, even his close friends, liked Shestov's ideas. Many thought he was giving up on reason and metaphysics, and some even saw his views as a form of nihilism (the belief that life has no meaning). However, writers like D.H. Lawrence and Georges Bataille admired his work.

Life in Exile

In 1908, Shestov moved to Freiburg, Germany, and then to a small Swiss village called Coppet in 1910. He wrote many books during this time, including Great Vigils and Penultimate Words.

He returned to Moscow in 1915, but sadly, his son Sergei died fighting the Germans that year. During his time in Moscow, his writings focused more on religion and theology.

Life became difficult for Shestov after the Bolsheviks took control of the government in 1917. The Marxists wanted him to write an introduction defending their ideas for his new book, Potestas Clavium. If he didn't, the book wouldn't be published. Shestov refused. However, he was allowed to teach about Greek philosophy at the University of Kiev.

Shestov disliked the Soviet government and eventually left Russia. He traveled a long way and finally settled in France. He became very popular in France, where people quickly recognized his unique ideas. In Paris, he soon became friends with and greatly influenced the young Georges Bataille. He was also close to Eugene and Olga Petit, who helped his family move to Paris and fit into French society.

His work was highly valued in France, and he was asked to write for a respected French philosophy journal. Between World War I and World War II, Shestov became a very important thinker. He spent this time studying great theologians like Blaise Pascal and Plotinus. He also lectured at the Sorbonne in 1925. In 1926, he met Edmund Husserl, another philosopher, and they remained friendly despite their different ideas. In 1929, during a visit to Freiburg, Husserl encouraged him to study the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

Discovering Kierkegaard

When Shestov discovered Kierkegaard, he realized their philosophies were very similar. Both rejected idealism (the idea that reality is based on ideas). Both believed that true knowledge comes from personal, subjective thought, not from objective reason or things that can be proven.

However, Shestov felt that Kierkegaard didn't take these ideas far enough. So, he continued where he thought Kierkegaard stopped. This led to his important book, Kierkegaard and Existential Philosophy: Vox Clamantis in Deserto, published in 1936. This book is a key work in Christian existentialism.

Despite his declining health, Shestov kept writing quickly. He finally finished his most important work, Athens and Jerusalem. This book explores the difference between freedom and reason. Shestov argued that reason should not be the main focus in philosophy. He also explained how the scientific method has made philosophy and science seem separate. Science focuses on what we can observe, but Shestov believed philosophy should deal with freedom, God, and immortality. These are topics that science cannot answer.

In 1938, Shestov became very ill while on vacation. During his final days, he continued his studies, focusing on Indian philosophy and the works of his friend Edmund Husserl, who had recently passed away. Shestov died at a clinic in Paris.

Shestov's Philosophy

Shestov's philosophy might seem unusual at first. It doesn't offer a clear, step-by-step system or a simple explanation for philosophical problems. Much of his work is made up of short, separate thoughts, often using aphorisms. His writing style is more like a web of ideas than a straight line of arguments.

He believed that life itself cannot be fully understood through logic or reason. Shestov argued that no deep philosophical thinking can truly solve life's mysteries. His philosophy wasn't about solving problems, but about highlighting how mysterious life is.

Questioning Reason

Shestov felt that philosophy often used reason to make humans and even God seem less important. He believed reason forced them to follow "necessities" – rules that are always true and unchangeable. Shestov didn't completely oppose reason or science. Instead, he challenged rationalism and scientism. These are the beliefs that reason is all-knowing and always right, like a god.

He pointed to philosophers like Aristotle, Spinoza, Kant, and Hegel. He felt they all believed in a fixed knowledge that could be found through reason. These included strict, logical rules like the law of non-contradiction, which Shestov thought would even limit God.

Shestov argued that this worship of reason comes from a fear of an unpredictable God. He believed it makes philosophers focus on what is unchanging or "dead," which goes against life and absolute freedom. Following Kierkegaard, Shestov argued that God means "nothing is impossible." This means absolute truth doesn't have to be limited by reason. So, we can't use reason to find final answers about how things *must* be.

By attacking these "obvious truths," Shestov suggested that we are often alone with our experiences and suffering. Philosophical systems cannot truly help us. Like Martin Luther, Dostoyevsky, and Kierkegaard, he believed true philosophy means thinking *against* the limits of reason. It only begins when "all possibilities have been exhausted" and "we run up against the wall of impossibility." His student, Benjamin Fondane, explained that real truth "begins beyond the limit of the logically impossible." This is why Shestov didn't have a neat, systematic philosophy. His ideas later influenced thinkers like Gilles Deleuze.

Despair as a Starting Point

Shestov's philosophy doesn't start with a theory or an idea. It begins with an experience: the feeling of despair. He described despair as losing certainty, losing freedom, and losing the meaning of life. This despair comes from what he called 'Necessity', 'Reason', 'Idealism', or 'Fate'. These are ways of thinking that force life to fit into ideas, general rules, and categories, which he felt killed its unique and living qualities.

However, despair is not the final answer for Shestov. It is only the "penultimate word" – the second-to-last word. The true final word cannot be put into human language or captured in a theory. His philosophy starts with despair, and his thinking is often desperate. But Shestov tried to point to something *beyond* despair, and beyond philosophy itself.

He called this 'faith'. For him, faith wasn't just a belief or a certainty. It was a different way of thinking that appears when we are in the deepest doubt and uncertainty.

Shestov, though a Jewish philosopher, saw the resurrection of Christ as a victory over these "necessities." He believed the incarnation (God becoming human) and resurrection of Jesus showed that life's purpose isn't to simply give up to an "absolute." Instead, it's about a difficult struggle:

"Why did He become man, suffer mistreatment, and die a painful death on the cross? Was it not to show us, through His example, that no decision is too hard? That it is worth bearing anything to avoid staying in the comfort of the 'One'? That any suffering for a living being is better than the 'happiness' of a perfectly still, 'ideal' being?"

Similarly, the last words of his final book, Athens and Jerusalem, are: "Philosophy is not thinking things over but struggle. And this struggle has no end and will have no end. The kingdom of God, as it is written, is attained through violence." (This refers to a verse in the Matthew 11:12).

Shestov's Influence

Shestov was highly respected by many thinkers. These included Nikolai Berdyaev and Sergei Bulgakov in Russia, Georges Bataille, Albert Camus, and Gilles Deleuze in France. In England, he influenced D.H. Lawrence, Isaiah Berlin, and John Middleton Murry. Among Jewish thinkers, he influenced Hillel Zeitlin.

Today, Shestov is not as well-known in English-speaking countries. This is partly because his books haven't always been easy to find. Also, the topics he discusses are sometimes seen as old-fashioned or "foreign." His writings have a serious yet exciting feeling. His ideas, which seem to question everything while also being religious, can appear confusing at first.

However, he did influence writers like Albert Camus, who wrote about him in The Myth of Sisyphus. He also influenced Benjamin Fondane (his student) and the poet Paul Celan. Notably, he influenced Emil Cioran, who said about Shestov:

"He was the philosopher of my generation, which didn't fully achieve its spiritual goals but still longed for them. Shestov [...] played an important role in my life. [...] He rightly thought that the true problems escape the philosophers. What else do they do but hide the real struggles of life?"

Shestov's work also appears in the writings of Gilles Deleuze, who mentions him in Nietzsche and Philosophy and Difference and Repetition.

Leo Strauss wrote "Jerusalem and Athens" partly as a response to Shestov's "Athens and Jerusalem."

More recently, many people have found comfort in Shestov's challenge to what seems rational and obvious, similar to Dostoyevsky's philosophy. For example, Bernard Martin of Case Western Reserve University translated Shestov's works, which are now available online. The scholar Liza Knapp also referred to Shestov in her book The Annihilation of Inertia: Dostoevsky and Metaphysics, which explored Dostoyevsky's struggle against fixed truths.

According to Michael Richardson's research on Georges Bataille, Shestov was an early influence on Bataille. Shestov introduced him to Nietzsche's ideas. Richardson believes Shestov's strong views on religion and interest in extreme human behavior likely shaped Bataille's own thoughts.

Main Works by Lev Shestov

Here are Shestov's most important works, with their English titles and the years they were written:

- The Good in the Teaching of Tolstoy and Nietzsche, 1899

- The Philosophy of Tragedy, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, 1903

- All Things are Possible (Apotheosis of Groundlessness), 1905

- Potestas Clavium, 1919

- In Job's Balances, 1923–29

- Kierkegaard and the Existential Philosophy, 1933–34

- Athens and Jerusalem, 1930–37

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Lev Shestov para niños

In Spanish: Lev Shestov para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |