Heinrich Heine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Heinrich Heine

|

|

|---|---|

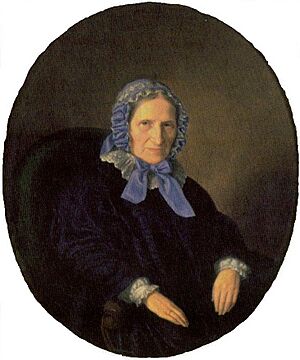

Painting of Heine by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim

|

|

| Born | Harry Heine 13 December 1797 Düsseldorf, Duchy of Berg, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 17 February 1856 (aged 58) Paris, Second French Empire |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist, journalist, literary critic |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | Bonn, Berlin, Göttingen |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was a famous German poet, writer, and literary critic. He is best known for his early poems, which were turned into songs called Lieder by composers like Robert Schumann and Franz Schubert.

Heine's later writings were known for their clever humor and irony. He was part of the "Young Germany" movement, a group of writers who wanted to see changes in German society. His strong political opinions caused many of his works to be banned in Germany. This ban, however, made him even more famous. He spent the last 25 years of his life living in Paris, France.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Youth

Heinrich Heine was born on December 13, 1797, in Düsseldorf, which was then part of the Duchy of Berg. He came from a Jewish family. As a child, he was called "Harry," but he became known as "Heinrich" after he converted to Lutheranism in 1825.

His father, Samson Heine, was a textile merchant. His mother, Peira (known as "Betty"), was the daughter of a doctor. Heinrich was the oldest of four children. He had a sister, Charlotte, and two brothers, Gustav and Maximilian. He was also a distant cousin of the famous thinker Karl Marx, with whom he later exchanged letters.

During Heine's childhood, Düsseldorf's political situation changed a lot. It was under French control when he was born. Then it became part of Napoleon's empire. After Napoleon's defeat in 1815, it became part of Prussia.

Because of this, Heine grew up with a strong French influence. He always admired the French for bringing new ideas like the Napoleonic Code (a set of laws) and trial by jury. He greatly respected Napoleon for promoting ideas of freedom and equality. Heine disliked the conservative politics in Germany after Napoleon's defeat.

Heine's parents were not very religious. He went to a Jewish school as a young child, where he learned some Hebrew. Later, he attended Catholic schools, where he learned French. French became his second language, and he always loved the local stories and traditions of the Rhineland.

In 1814, Heine went to a business school in Düsseldorf to learn English. The most successful person in his family was his uncle, Salomon Heine, a rich banker in Hamburg. In 1816, Heine moved to Hamburg to work for his uncle's bank. However, he was not good at business and disliked the city's focus on money.

When he was 18, Heine likely fell in love with his cousin Amalie, Salomon's daughter, but she did not return his feelings. His father's business struggled, and his family became dependent on his uncle Salomon.

University Life

Salomon realized that Heine was not suited for business. So, in 1819, Heine went to the University of Bonn to study law. At that time, Germany was divided between conservatives and liberals. Conservatives wanted to keep things as they were before the French Revolution. They were against a united Germany because they feared new, revolutionary ideas. Most German states were ruled by kings with strict censorship.

Liberals, on the other hand, wanted a government where people had a say, with a constitution, equal rights, and a free press. Heine was a strong liberal. At Bonn, he joined a student parade that went against strict government rules meant to stop liberal activities.

Heine was more interested in history and literature than law. He listened to lectures by the famous critic August Wilhelm Schlegel, who taught about German legends and Romanticism. Heine started to gain a reputation as a poet at Bonn. He also wrote two plays, Almansor and William Ratcliff, but they were not very successful.

After a year, Heine moved to the University of Göttingen to continue his law studies. He disliked Göttingen, partly because it was ruled by the United Kingdom, which he blamed for Napoleon's defeat. He also found the law studies boring and felt that the university had an unfriendly, snobby atmosphere. He was even suspended from the university for six months after challenging another student to a duel.

His uncle then sent him to the University of Berlin.

Heine arrived in Berlin in March 1821. It was a large, exciting city. At the university, he met important cultural figures. The philosopher Hegel was especially important, as he taught Heine and other young students that history had a progressive meaning. Heine also made friends with liberal thinkers like Karl August Varnhagen von Ense and his wife Rahel Varnhagen, who hosted popular gatherings.

Another friend was the writer Karl Immermann, who praised Heine's first collection of poems, Gedichte, published in December 1821. In Berlin, Heine also joined a society that tried to connect Jewish faith with modern ideas. Though not very religious, he became interested in Jewish history, especially the Spanish Jews of the Middle Ages. In 1824, he started a historical novel, Der Rabbi von Bacherach, but never finished it.

In May 1823, Heine left Berlin and joined his family in Lüneburg. There, he began writing poems for his collection Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming"). He returned to Göttingen but was still bored by law. In September 1824, he took a trip through the Harz mountains, which inspired his travel book, Die Harzreise.

On June 28, 1825, Heine converted to Protestantism. The Prussian government was making it harder for Jewish people to get certain jobs, including university positions, which Heine wanted. He said his conversion was "the ticket of admission into European culture." However, this reluctant conversion did not actually help his career much.

First Literary Successes

Heine needed to find a job, but it was hard to be a professional writer in Germany. The market for books was small, and writers had to work constantly to make a living. Heine found this difficult and often struggled financially. Before finding work, he visited the North Sea resort of Norderney, which inspired his poems in the cycle Die Nordsee.

In January 1826, Heine met Julius Campe in Hamburg, who would become his main publisher. Their relationship was often difficult. Campe was a liberal publisher who tried to publish authors who disagreed with the government. He had ways to get around censorship laws. For example, books under 320 pages had to be censored, so he would print books in large type to make them longer than 320 pages.

Censorship in Hamburg was not as strict, but Campe also had to worry about Prussia, which was the largest German state and the biggest market for books. Heine, however, hated all censorship, which caused arguments between them.

Despite their disagreements, their relationship started well. Campe published the first volume of Reisebilder ("Travel Pictures") in May 1826. This book included Die Harzreise, which introduced a new style of German travel writing, mixing beautiful descriptions of nature with satire.

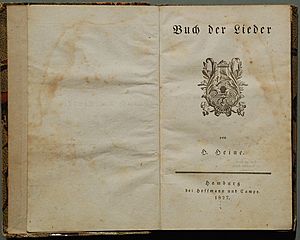

Heine's Buch der Lieder ("Book of Songs") followed in 1827. This was a collection of poems he had already published. It became one of the most popular German poetry books ever, especially as composers began setting Heine's poems to music as Lieder (art songs). For example, the poem "Allnächtlich im Traume" was set to music by Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn.

Allnächtlich im Traume seh ich dich,

Und sehe dich freundlich grüßen,

Und laut aufweinend stürz ich mich

Zu deinen süßen Füßen.

Du siehst mich an wehmütiglich,

Und schüttelst das blonde Köpfchen;

Aus deinen Augen schleichen sich

Die Perlentränentröpfchen.

Du sagst mir heimlich ein leises Wort,

Und gibst mir den Strauß von Zypressen.

Ich wache auf, und der Strauß ist fort,

Und das Wort hab ich vergessen.

Nightly I see you in dreams – you speak,

With kindliness sincerest,

I throw myself, weeping aloud and weak

At your sweet feet, my dearest.

You look at me with wistful woe,

And shake your golden curls;

And stealing from your eyes there flow

The teardrops like to pearls.

You breathe in my ear a secret word,

A garland of cypress for token.

I wake; it is gone; the dream is blurred,

And forgotten the word that was spoken.

(Poetic translation by Hal Draper)

From the mid-1820s, Heine started to move away from Romanticism. He added irony, sarcasm, and satire to his poems, often making fun of the overly emotional way nature was described in poetry. Here is an example:

Das Fräulein stand am Meere

Und seufzte lang und bang.

Es rührte sie so sehre

der Sonnenuntergang.

Mein Fräulein! Sein sie munter,

Das ist ein altes Stück;

Hier vorne geht sie unter

Und kehrt von hinten zurück.

A mistress stood by the sea

sighing long and anxiously.

She was so deeply stirred

By the setting sun

My Fräulein!, be gay,

This is an old play;

ahead of you it sets

And from behind it returns.

Heine became more and more critical of strict rulers and narrow-minded nationalism in Germany. He criticized the nobility, the clergy, and even ordinary people's limited views. He especially disliked the rising German nationalism when compared to the French and their revolution.

Travel and Disagreements

The first volume of his travel writings was so popular that Campe asked Heine for another. Reisebilder II came out in April 1827. It included more North Sea poems and an essay called Ideen: Das Buch Le Grand, which criticized German censorship.

Heine went to England to avoid the controversy he expected from this new book. He found the English people too focused on business and still blamed them for Napoleon's defeat.

When he returned to Germany, a liberal publisher named Johann Friedrich Cotta offered Heine a job editing a magazine in Munich. Heine didn't enjoy newspaper work and tried to get a professorship at Munich University, but he was unsuccessful. After a few months, he traveled to northern Italy, visiting Lucca, Florence, and Venice. He had to return when he heard his father had died. This trip inspired new works, including Die Reise von München nach Genua (Journey from Munich to Genoa) and Die Bäder von Lucca (The Baths of Lucca).

Die Bäder von Lucca caused a big argument. Another poet, August von Platen, had been upset by some poems Heine included in his second Reisebilder volume. Platen wrote a play that included anti-Jewish insults about Heine. Heine was hurt and responded by making fun of Platen in Die Bäder von Lucca. This back-and-forth literary fight became known as the Platen affair.

Life in Paris

Moving to France

Heine left Germany for France in 1831 and lived in Paris for the rest of his life. He moved because of the July Revolution of 1830 in France, which brought Louis-Philippe to power as the "Citizen King." Heine was excited by this revolution, believing it could change the conservative political system in Europe. He also wanted to escape German censorship and was interested in a new French political idea called Saint-Simonianism. This idea promoted a new society where talent, not family background or wealth, would determine a person's place. It also supported women's rights and a key role for artists and scientists. Heine attended some Saint-Simonian meetings but soon lost interest.

Heine quickly became well-known in France. Paris offered him a rich cultural life that was not available in smaller German cities. He met many famous people, including Gérard de Nerval and Hector Berlioz. However, he always felt a bit like an outsider. He wasn't very interested in French literature and wrote everything in German, then had it translated into French with help.

In Paris, Heine earned money as the French correspondent for one of Cotta's newspapers, the Allgemeine Zeitung. His articles were later collected in a book called Französische Zustände ("Conditions in France"). Heine saw himself as a bridge between Germany and France, believing that if the two countries understood each other, progress would happen. To help with this, he published De l'Allemagne ("On Germany") in French. In its German version, this book was divided into two parts: Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany") and Die romantische Schule ("The Romantic School"). Heine was deliberately challenging another book called De l'Allemagne (1813) by Madame de Staël, which he thought was too traditional and old-fashioned. He felt de Staël showed Germany as a land of "poets and thinkers" that was dreamy, religious, and separate from modern revolutionary ideas. Heine believed this image suited the strict German authorities.

Heine had not had many serious romantic relationships, but in late 1834, he met Crescence Eugénie Mirat, a 19-year-old shopgirl in Paris, whom he called "Mathilde." She couldn't read or write, knew no German, and wasn't interested in cultural or intellectual topics. Despite this, she moved in with Heine in 1836, and they lived together for the rest of his life. They married in 1841.

Young Germany and Political Views

Heine and another German writer living in Paris, Ludwig Börne, became role models for a younger group of writers called "Young Germany". This group included writers like Karl Gutzkow and Heinrich Laube. They were liberal thinkers, but not always directly involved in politics. Still, the authorities disliked them.

In 1835, Gutzkow published a novel that criticized marriage. In November of that year, the German government banned the works of the Young Germans in Germany. At the insistence of the Austrian chancellor Klemens von Metternich, Heine's name was added to the list of banned authors. However, Heine continued to write about German politics and society from Paris. His publisher found ways to get around the censors, and he was still free to publish in France.

Heine's relationship with Ludwig Börne was difficult. Börne was very popular among German immigrant workers in Paris and was a republican, while Heine was not. Heine saw Börne as too strict and avoided him in Paris, which upset Börne. Börne started to criticize Heine privately. Börne died in February 1837. When Heine heard that someone was writing a biography of Börne, he started writing his own very critical "memorial" about him.

When Heine's book about Börne was published in 1840, many people disliked it. Even Börne's enemies admitted he was an honest person, so Heine's personal attacks were seen as unfair. Heine had made personal attacks on Börne's close friend, which led to a duel. It was the last duel Heine ever fought, and he was wounded in the hip. Before the duel, he decided to marry Mathilde to make sure she would be taken care of if he died.

Heine continued to write for Cotta's newspaper. One event that deeply affected him was the 1840 Damascus Affair. In Damascus, Jewish people were falsely accused of murdering a monk, leading to a wave of anti-Jewish persecution.

Heine was upset that the French government did not strongly condemn this injustice. He felt that Austria, a more conservative country, had stood up for the Jews, while France had hesitated. In response, Heine published his unfinished novel about the persecution of Jews in the Middle Ages, Der Rabbi von Bacherach.

Political Poetry and Karl Marx

German poetry became more political when the new king, Frederick William IV, came to power in Prussia in 1840. At first, people thought he might be a more open-minded ruler, and censorship was relaxed for a short time (1840–42). This led to the rise of popular political poets, including Hoffmann von Fallersleben (who wrote the German national anthem). Heine didn't think these writers were very good poets, but his own poems in the 1840s also became more political.

Heine's style was satirical attack. He criticized the kings of Bavaria and Prussia, the lack of political action by the German people, and the greed of the ruling class. One of his most famous political poems was Die schlesischen Weber ("The Silesian Weavers"), which was about an uprising of weavers in 1844.

In October 1843, Heine's distant relative, the German revolutionary Karl Marx, arrived in Paris with his wife Jenny von Westphalen. The Prussian government had shut down Marx's radical newspaper. Marx admired Heine, and his early writings showed Heine's influence. In December, Heine met the Marxes and they got along well. Heine published several poems, including Die schlesischen Weber, in Marx's new journal Vorwärts ("Forwards").

Although their ideas about revolution were different, both writers shared a dislike for the middle class. Marx's friendship was a comfort to Heine, who didn't really like the other radical thinkers. However, Heine didn't share Marx's belief in the industrial working class and stayed somewhat separate from socialist groups. The Prussian government pressured France to deal with the authors of Vorwärts, and Marx was deported in January 1845. Heine could not be expelled because he had been born under French occupation, giving him the right to live in France. After this, Heine and Marx wrote to each other sometimes, but their admiration for each other faded. Heine always had mixed feelings about communism. He worried that its radical ideas might destroy much of the European culture he loved.

In the French edition of "Lutetia," written a year before he died, Heine wrote about his fear of the future if communists came to power. He worried they would destroy art and old traditions. Yet, he also felt a "magical appeal" to these ideas because of logic (everyone has a right to eat) and his hatred for German nationalists who disliked other countries, especially France.

In late 1843, Heine traveled to Hamburg to see his elderly mother and to make up with Campe, his publisher, after a quarrel. They reconciled, and Campe agreed to provide Mathilde with money for the rest of her life after Heine's death. Heine made another trip with his wife in 1844 to see his Uncle Salomon, but this visit did not go well. This was the last time Heine left France.

At this time, Heine was working on two related but opposite poems: Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen (Germany. A Winter's Tale) and Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum (Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream). Deutschland was based on his trip to Germany in 1843 and strongly criticized the political situation there. Atta Troll (started in 1841) made fun of the literary weaknesses Heine saw in other radical poets. It tells the story of hunting a runaway bear, Atta Troll, who represents ideas Heine disliked, such as simple equality and a religious view that makes God in one's own image.

Atta Troll was published in 1847, but Deutschland appeared in 1844 as part of a collection called Neue Gedichte ("New Poems"), which included all the poems Heine had written since 1831. In the same year, Uncle Salomon died. This stopped Heine's yearly payment of 4,800 francs. Salomon left Heine and his brothers 8,000 francs each in his will. Heine's cousin Carl, who inherited Salomon's business, offered to pay him 2,000 francs a year at his own choice. Heine was furious, expecting much more, and spent the next two years trying to get Carl to change the will.

Final Years and Legacy

The "Mattress-Grave"

In May 1848, Heine, who had been unwell, suddenly became paralyzed and had to stay in bed. He called this his "mattress-grave" (Matratzengruft), and he remained there until his death eight years later. He also had problems with his eyes. It was later suggested that he suffered from multiple sclerosis, though in 1997, analysis of his hair showed he had chronic lead poisoning. He bravely endured his suffering and gained much public sympathy. His illness meant he paid less attention to the revolutions that broke out in France and Germany in 1848. He was doubtful about the Frankfurt Parliament and continued to criticize the King of Prussia.

When the revolution failed, Heine continued his opposition. At first, he hoped Louis Napoleon might be a good leader in France, but he soon agreed with Marx that the new emperor was cracking down on liberal and socialist ideas. In 1848, Heine also returned to religious faith, though he remained skeptical of organized religion.

He continued to write from his sickbed. He produced the poetry collections Romanzero and Gedichte (1853 und 1854), the journalism collected in Lutezia, and his unfinished memoirs. During these last years, Heine had a close friendship with a young woman named Camille Selden, who visited him regularly. He died on February 17, 1856, and was buried in the Paris Cimetière de Montmartre.

His tomb was designed by the Danish sculptor Louis Hasselriis. It has Heine's poem Where? (German: Wo?) carved on three sides of the tombstone.

Wo wird einst des Wandermüden

Letzte Ruhestätte sein?

Unter Palmen in dem Süden?

Unter Linden an dem Rhein?

Werd ich wo in einer Wüste

Eingescharrt von fremder Hand?

Oder ruh ich an der Küste

Eines Meeres in dem Sand?

Immerhin! Mich wird umgeben

Gotteshimmel, dort wie hier,

Und als Totenlampen schweben

Nachts die Sterne über mir.

Where shall I, the wander-wearied,

Find my haven and my shrine?

Under palms will I be buried?

Under lindens on the Rhine?

Shall I lie in desert reaches,

Buried by a stranger's hand?

Or upon the well-loved beaches,

Covered by the friendly sand?

Well, what matter! God has given

Wider spaces there than here.

And the stars that swing in heaven

Shall be lamps above my bier.

(translation in verse by L.U.)

His wife Mathilde outlived him, dying in 1883. They did not have any children.

Heine's Enduring Influence

Heinrich Heine's works were among the thousands of books burned by the Nazis in Berlin in 1933. To remember this event, one of Heine's most famous lines from his 1821 play Almansor was engraved on the ground at the site: "Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen." This means: "That was just the beginning; where they burn books, they will eventually burn people as well."

The Nazis hated Heine's writings. They called his work "degenerate" and tried to hide his contributions to German art and culture. All monuments to Heine were removed or destroyed during Nazi Germany, and his books were banned from 1940 onwards. However, many songs based on Heine's poems were so popular that it was hard to stop people from enjoying them.

Music and Heine

Many composers have set Heine's poems to music. These include Robert Schumann (especially his song cycle Dichterliebe), Friedrich Silcher (who wrote a popular setting of "Die Lorelei," one of Heine's most famous poems), Franz Schubert, Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn, Fanny Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward MacDowell, Elise Schmezer, Sophie Seipt, Charlotte Sporleder, Maria Anna Stubenberg, Pauline Volkstein, Clara Schumann, and Richard Wagner. In the 20th century, composers like Nikolai Medtner, Lola Carrier Worrell, Hans Werner Henze, Carl Orff, and Marcel Tyberg also used his words.

Heine's play William Ratcliff was used for the stories of operas by César Cui (William Ratcliff) and Pietro Mascagni (Guglielmo Ratcliff).

In 1964, Gert Westphal and the Attila-Zoller Quartet released a vinyl record called "Heinrich Heine Lyrik und Jazz," combining his poetry with jazz music.

Composer Wilhelm Killmayer set 37 of Heine's poems in his songbook Heine-Lieder in 1994.

Morton Feldman's music piece I Met Heine on the Rue Fürstemberg was inspired by a vision he had of Heine while walking in Paris. Feldman felt a strong connection to Heine as a "Jewish exile."

Major Works

Here is a list of Heine's main publications in German:

- 1820: Die Romantik ("Romanticism," a short critical essay)

- 1821: Gedichte ("Poems")

- 1822: Briefe aus Berlin ("Letters from Berlin")

- 1823: Über Polen ("On Poland," a prose essay)

- 1823: Tragödien nebst einem lyrischen Intermezzo ("Tragedies with a Lyrical Intermezzo") which includes:

- Almansor (play, written 1821–1822)

- William Ratcliff (play, written January 1822)

- Lyrisches Intermezzo (a cycle of poems)

- 1826: Reisebilder. Erster Teil ("Travel Pictures I"), contains:

- Die Harzreise ("The Harz Journey," a prose travel work)

- Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming," poems)

- Die Nordsee. Erste Abteilung ("North Sea I," a cycle of poems)

- 1827: Reisebilder. Zweiter Teil ("Travel Pictures II"), contains:

- Die Nordsee. Zweite Abteilung ("The North Sea II," a cycle of poems)

- Die Nordsee. Dritte Abteilung ("The North Sea III," a prose essay)

- Ideen: das Buch le Grand ("Ideas: The Book of Le Grand")

- Briefe aus Berlin ("Letters from Berlin," a shorter version of the 1822 work)

- 1827: Buch der Lieder ("Book of Songs"); a collection of poems including:

- Junge Leiden ("Youthful Sorrows")

- Die Heimkehr ("The Homecoming," first published 1826)

- Lyrisches Intermezzo ("Lyrical Intermezzo," first published 1823)

- "Aus der Harzreise" (poems from Die Harzreise, first published 1826)

- Die Nordsee ("The North Sea: Cycles I and II," first published 1826/1827)

- 1829: Reisebilder. Dritter Teil ("Travel Pictures III"), contains:

- Die Reise von München nach Genua ("Journey from Munich to Genoa," a prose travel work)

- Die Bäder von Lucca ("The Baths of Lucca," a prose travel work)

- Anno 1829

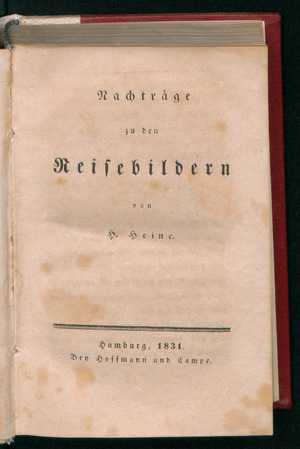

- 1831: Nachträge zu den Reisebildern ("Supplements to the Travel Pictures"), later called Reisebilder. Vierter Teil ("Travel Pictures IV"), contains:

- Die Stadt Lucca ("The Town of Lucca," a prose travel work)

- Englische Fragmente ("English Fragments," travel writings)

- 1831: Zu "Kahldorf über den Adel" (introduction to a book, uncensored version published in 1890)

- 1833: Französische Zustände ("Conditions in France," collected journalism)

- 1833: Der Salon. Erster Teil ("The Salon I"), contains:

- Französische Maler ("French Painters," criticism)

- Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski ("From the Memoirs of Herr Schnabelewopski," an unfinished novel)

- 1835: Der Salon. Zweiter Teil ("The Salon II"), contains:

- Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland ("On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany")

- Neuer Frühling ("New Spring," a cycle of poems)

- 1835: Die romantische Schule ("The Romantic School," criticism)

- 1837: Der Salon. Dritter Teil ("The Salon III"), contains:

- Florentinische Nächte ("Florentine Nights," an unfinished novel)

- Elementargeister ("Elemental Spirits," an essay on folklore)

- 1837: Über den Denunzianten. Eine Vorrede zum dritten Teil des Salons. ("On the Denouncer. A Preface to Salon III," a pamphlet)

- 1837: Einleitung zum "Don Quixote" ("Introduction to Don Quixote," a preface to a new German translation)

- 1838: Der Schwabenspiegel ("The Mirror of Swabia," a prose work criticizing poets of the Swabian School)

- 1838: Shakespeares Mädchen und Frauen ("Shakespeare's Girls and Women," essays on female characters in Shakespeare's plays)

- 1839: Anno 1839

- 1840: Ludwig Börne. Eine Denkschrift ("Ludwig Börne: A Memorial," a long prose work about the writer Ludwig Börne)

- 1840: Der Salon. Vierter Teil ("The Salon IV"), contains:

- Der Rabbi von Bacherach ("The Rabbi of Bacharach," an unfinished historical novel)

- Über die französische Bühne ("On the French Stage," prose criticism)

- 1844: Neue Gedichte ("New Poems"); contains:

- Neuer Frühling ("New Spring," first published in 1834)

- Verschiedene ("Sundry Women")

- Romanzen ("Ballads")

- Zur Ollea ("Olio")

- Zeitgedichte ("Poems for the Times")

- it also includes Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen (Germany. A Winter's Tale, a long poem)

- 1847: Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum (Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night's Dream, a long poem, written 1841–46)

- 1851: Romanzero; a collection of poems divided into three books:

- Erstes Buch: Historien ("First Book: Histories")

- Zweites Buch: Lamentationen ("Second Book: Lamentations")

- Drittes Buch: Hebräische Melodien ("Third Book: Hebrew Melodies")

- 1851: Der Doktor Faust. Tanzpoem ("Doctor Faust. Dance Poem," a ballet story, written 1846)

- 1854: Vermischte Schriften ("Miscellaneous Writings") in three volumes, contains:

- Volume One:

- Geständnisse ("Confessions," an autobiographical work)

- Die Götter im Exil ("The Gods in Exile," a prose essay)

- Die Göttin Diana ("The Goddess Diana," a ballet story, written 1846)

- Ludwig Marcus: Denkworte ("Ludwig Marcus: Recollections," a prose essay)

- Gedichte. 1853 und 1854 ("Poems. 1854 and 1854")

- Volume Two:

- Lutezia. Erster Teil ("Lutetia I," collected journalism about France)

- Volume Three:

- Lutezia. Zweiter Teil ("Lutetia II," collected journalism about France)

- Volume One:

Published After His Death

- Memoiren ("Memoirs," first published in 1884).

English Editions

- Poems of Heinrich Heine, Three hundred and Twenty-five Poems, Translated by Louis Untermeyer, Henry Holt, New York, 1917.

- The Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine: A Modern English Version by Hal Draper, Suhrkamp/Insel Publishers Boston, 1982. ISBN: 3-518-03048-5

- Religion and Philosophy in Germany, a fragment, Tr. James Snodgrass, 1959. Boston, MA (Beacon Press). Available online.

See Also

In Spanish: Heinrich Heine para niños

In Spanish: Heinrich Heine para niños

- Die Lotosblume

- On Wings of Song (poem and song)

- Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf

- Heinrich Heine Prize

- The Gaze of the Gorgon