Henri de Saint-Simon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henri de Saint-Simon

|

|

|---|---|

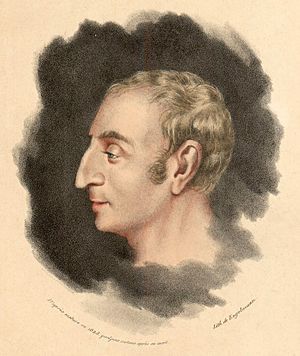

Posthumous portrait (1848);

after Adélaïde Labille-Guiard |

|

| Born |

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon

17 October 1760 |

| Died | 19 May 1825 (aged 64) Paris, France

|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Saint-Simonianism Socialism Utopian socialism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

The industrial class/idling class distinction |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (born October 17, 1760 – died May 19, 1825), often called Henri de Saint-Simon, was a French thinker. He focused on politics, economics, and society. His ideas greatly influenced how people thought about politics, money, and how society works. He was a distant relative of the famous writer, the Duc de Saint-Simon.

Saint-Simon developed an idea called Saint-Simonianism. He believed that society needed to recognize and support the "industrial class." He also called this the "working class." For him, this class included everyone who did productive work. This meant business people, scientists, bankers, and manual laborers.

He thought that the biggest problem for the industrial class was the "idling class." These were people who could work but chose to live off others. Saint-Simon believed that people should be rewarded based on their skills and hard work. He wanted society to be led by skilled managers and scientists. He also felt the government should not interfere too much in the economy. Its main job was to make sure people could work productively and to reduce laziness.

Saint-Simon's ideas inspired many later thinkers. These included utopian socialists, John Stuart Mill, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and even Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. His views also influenced the economist Thorstein Veblen in the 20th century.

Contents

About Henri de Saint-Simon

His Early Life

Henri de Saint-Simon was born in Paris, France. He came from a noble family. As a young man, he was very adventurous. He traveled to America and joined the American forces. He fought in the siege of Yorktown with George Washington.

Saint-Simon was very ambitious from a young age. He even told his servant to wake him up every morning with the reminder, "Remember, monsieur le comte, that you have great things to do." He had big plans, like digging a canal to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He also dreamed of a canal from Madrid to the sea.

During the American Revolution, Saint-Simon believed it was the start of a new era. He fought alongside the Marquis de Lafayette. He was captured by the British but later released. After this, he returned to France to study engineering.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, Saint-Simon supported its ideals of liberty, equality, and brotherhood. He tried to set up a large industrial system. He also wanted to create a scientific school. He raised money by buying and selling land. However, the political situation in France became very unstable. This made it hard for him to continue his business. He was even put in prison for a time. He was released in 1794. After his release, he became very wealthy due to changes in money value. But his business partner later stole his fortune. After this, he decided to focus on studying politics and research.

His Adult Life and Work

Around the age of 40, Saint-Simon studied many different subjects. He wanted to understand the world better. He even got married in 1801 to have a place for people to meet and discuss ideas. But the marriage ended after a year.

After his studies, he became very poor. He lived in poverty for the rest of his life. His first book, Lettres d'un habitant de Genève, came out in 1802. In this book, he suggested creating a "religion of science." He even thought Isaac Newton could be like a saint in this new religion. Around 1814, he wrote about rebuilding Europe. He suggested a European kingdom based on France and the United Kingdom.

In 1817, he started to share his socialist ideas in a book called L'Industrie. He continued to develop these ideas in a magazine called L'Organisateur. In this magazine, he worked with Augustin Thierry and Auguste Comte. One of Saint-Simon's main beliefs was that the world should be connected by canals.

L'Industrie caused a stir, but it didn't gain many followers. A few years later, Saint-Simon was broke again and had to work. He received some financial help from a former employee, Diard. This allowed him to publish his second book in 1807. After Diard died in 1810, Saint-Simon became poor and sick again. He was sent to a special hospital in 1813. But with help from his family, he got better. He also started to gain some recognition for his ideas in Europe. He published more works, including Du système industriel in 1821 and Catéchisme des industriels in 1823–1824.

His Death and Lasting Impact

Late in his life, he finally found a few dedicated followers. His most important work, Nouveau Christianisme (New Christianity), was published in 1825. He died before he could finish it.

He was buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France.

Saint-Simon's Main Ideas

Industrialism: A New Society

In 1817, Saint-Simon published a paper called the "Declaration of Principles." It was part of his work L'Industrie ("Industry"). This paper explained his idea of industrialism. He wanted to create an industrial society. This society would be led by people from what he called the "industrial class."

The industrial class, also known as the working class, included everyone who did useful work for society. He especially highlighted scientists and business owners. But it also included engineers, managers, bankers, and manual workers.

Saint-Simon believed the main threat to the industrial class was the "idling class." These were people who could work but chose to be lazy. They lived off the work of others. He thought this laziness was a natural human trait. He believed the government's main jobs were to make sure productive work was not stopped. It also needed to reduce idleness in society.

In his "Declaration," Saint-Simon strongly criticized too much government involvement in the economy. He said that if the government did more than these two main jobs, it would become a "tyrannical enemy of industry." He thought too much government control would make the economy worse. Saint-Simon emphasized that people should be recognized for their skills and hard work. He wanted society and the economy to have a system where the most skilled people were in charge. For example, he thought skilled managers and scientists should make government decisions. These ideas were very new for his time. He built on ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. These ideas challenged old church rules and the old system. They promoted progress through industry and science.

Saint-Simon was influenced by what he saw in the early United States. He noticed there was less social privilege there. He gave up his own noble title. He came to believe in a system where people gained power based on their abilities, called a meritocracy. He was convinced that science was the key to progress. He thought society could be built on fair, scientific rules. He argued that the old feudal society in France needed to change. It should become an industrial society. He was the first to use the idea of an "industrial society."

Saint-Simon's economic ideas were influenced by Adam Smith. Saint-Simon greatly admired Smith, calling him "the immortal Adam Smith." Like Smith, he believed taxes should be much lower for a fairer industrial system. Saint-Simon wanted the government to interfere as little as possible in the economy. He thought this would prevent problems for productive work. He stressed even more than Smith that government control of the economy was usually harmful. It was like a parasite and hurt production. Like Adam Smith, Saint-Simon's ideas for society were inspired by the scientific methods of astronomy. He said, "The astronomers only accepted those facts which were verified by observation; they chose the system which linked them best, and since that time, they have never led science astray."

Saint-Simon looked at the French Revolution. He saw it as a big change caused by economic shifts and class conflict. He believed the problems that led to the revolution could be solved by creating an industrial society. In this society, people would be respected for their skills and productive work. Old systems based on birth or military rank would become less important. This is because they were not good at leading a productive society.

Karl Marx called Saint-Simon one of the "utopian socialists." However, some historians believe Saint-Simon's followers, not Saint-Simon himself, were more responsible for the rise of utopian socialism. Saint-Simon's ideas were different from Marx's in some ways. Saint-Simon did not push for workers to organize on their own. He also didn't define the working class in the same way Marx did. Unlike Marx, Saint-Simon didn't see class struggles as the main driver of social change. Instead, he focused on how society was managed. He also saw business owners as an important part of the "industrial class." By the 1950s, it was clear that Saint-Simon had predicted the modern idea of an industrial society.

His Religious Views

Before his book Nouveau Christianisme (New Christianity), Saint-Simon didn't focus on religion. In this book, he starts by believing in God. His goal was to simplify Christianity to its basic ideas. He wanted to remove the complex rules and problems he saw in the Catholic and Protestant religions. He proposed a simple rule for his new Christianity: "The whole of society ought to strive towards the improvement of the moral and physical existence of the poorest class; society ought to organize itself in the way best adapted for attaining this end." This idea became very important for all of Saint-Simon's followers.

Saint-Simon's Influence

Philosophical Impact

During his lifetime, Saint-Simon's ideas didn't have much impact. He left behind only a few dedicated followers. They continued to spread his teachings. His most famous student was Auguste Comte. Other important followers included Olinde Rodrigues and Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin. These two received Saint-Simon's last instructions. They first started a journal, but it stopped in 1826.

The group of followers grew. By 1828, they held meetings in Paris and other towns. A big step for the group happened in 1828. Amand Bazard gave a full explanation of the Saint-Simonian beliefs in lectures in Paris. Many people attended. His book, Exposition de la doctrine de St Simon, gained more followers. The second part of the book was mostly by Enfantin. Enfantin and Bazard led the group. Enfantin was more philosophical and pushed ideas to their limits. The July Revolution of 1830 gave more freedom to social reformers. The group announced they wanted shared ownership of goods. They also wanted to end the right to inherit property and give women the right to vote.

The next year, the group took over a newspaper called Le Globe. Many smart and promising young people in France joined the movement. Many students from the École Polytechnique were excited by its ideas. The members formed a group with three levels. They lived together in a shared home in Paris. But soon, disagreements started within the group. Bazard could not work with Enfantin. Enfantin wanted to create a strange and proud religious system. Enfantin also said that the differences between men and women were too great. He believed this inequality would slow down society's progress. Enfantin called for women to be able to divorce and have legal rights. This was a very radical idea for the time.

Bazard left the group, and many strong supporters followed him. The group spent a lot of money on parties in the winter of 1832. This hurt their finances and their reputation. They moved to Enfantin's property, where they lived in a communal way. They even wore special clothes. Soon after, the leaders were put on trial. They were found guilty of actions that harmed social order. The group completely broke up in 1832. Many of its members later became famous engineers, economists, and business people. Enfantin later organized a trip for his followers to Constantinople and then to Egypt. There, he helped influence the creation of the Suez Canal.

The French feminist and socialist writer Flora Tristan (1803–1844) believed that Mary Wollstonecraft had similar ideas to Saint-Simon a generation earlier.

Literary Impact

In Fyodor Dostoyevsky's novel The Possessed, the terms 'Saint-Simonist' and 'Fourierist' are used as insults. Characters use them against others who are politically active.

According to Fr. Cyril Martindale, Robert Hugh Benson got the idea for his novel Lord of the World from his friend Frederick Rolfe. Rolfe introduced Benson to Saint-Simon's writings. As Benson read Saint-Simon, he imagined a world without Christianity. This world came from the collapse of the old system. Rolfe suggested Benson write a book about the Antichrist.

Saint-Simon's Writings

Saint-Simon wrote several books and essays explaining his ideas:

- Lettres d'un habitant de Genève à ses contemporains (1803)

- L'Industrie (1816–1817)

- Le Politique (1819)

- L'Organisateur (1819–1820)

- Du système industriel (1822)

- Catéchisme des industriels (1823–1824)

- Nouveau Christianisme (1825)

- A collection of the works of Saint-Simon and Enfantin was published by the followers (47 volumes, Paris, 1865–1878).

See also

In Spanish: Henri de Saint-Simon para niños

In Spanish: Henri de Saint-Simon para niños

- French Revolution

- Meritocracy

- Positivism

- Scientism

- Society of the Friends of Truth

- Utopian socialism

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |