Bourbon Restoration in France facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of France

Royaume de France (French)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814–1815 1815–1830 |

|||||||||||

|

Motto: Montjoie Saint Denis!

"Montjoy Saint Denis!" |

|||||||||||

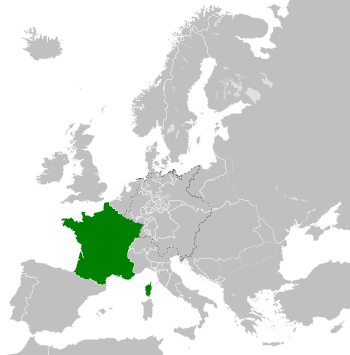

The Kingdom of France in 1818

|

|||||||||||

| Capital | Paris | ||||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (State religion) Calvinism Lutheranism Judaism |

||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | French | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• 1814–1824

|

Louis XVIII | ||||||||||

|

• 1824–1830

|

Charles X | ||||||||||

|

• 1830

|

Louis XIX (disputed) |

||||||||||

| President of the Council of Ministers | |||||||||||

|

• 1815 (first)

|

Charles de Talleyrand-Périgord | ||||||||||

|

• 1829–1830 (last)

|

Jules de Polignac | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||||

| Chamber of Peers | |||||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 3 May 1814 | |||||||||||

| 30 May 1814 | |||||||||||

| 4 June 1814 | |||||||||||

| 20 Mar – 7 Jul 1815 | |||||||||||

| 6 April 1823 | |||||||||||

| 26 July 1830 | |||||||||||

| Currency | French franc | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FR | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

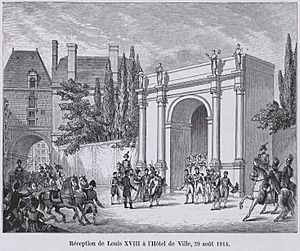

The Bourbon Restoration was a time in French history when the House of Bourbon royal family returned to power. This happened after Napoleon was first defeated on May 3, 1814. The Restoration was briefly stopped in 1815 by the "Hundred Days" when Napoleon came back. But it continued until the July Revolution on July 26, 1830.

During this period, Louis XVIII and Charles X, who were brothers of the king Louis XVI (who had been executed), became kings. They tried to bring back some of the old traditions and ways of the monarchy, though not everything from before the French Revolution. Many people who had supported the monarchy and left France during the Revolution came back. However, they couldn't undo most of the big changes the Revolution had made. After many years of fighting in the Napoleonic Wars, France finally had a time of peace, a strong economy, and the beginnings of new industries.

Contents

- How the Monarchy Returned

- France's New Government: A Constitutional Monarchy

- Big Changes That Stayed in France

- Political Scene During the Restoration

- Louis XVIII's Reign (1814–1824)

- Charles X's Reign (1824–1830)

- Louis-Philippe and the Orléans Family

- Political Groups During the Restoration

- Religion in France

- Economy During the Restoration

- Art and Literature of the Time

- Paris During the Restoration

- How History Views the Restoration

- The Restoration in Recent Pop Culture

- See also

- Images for kids

How the Monarchy Returned

After the French Revolution (1789–1799), Napoleon Bonaparte became the powerful ruler of France. His French Empire grew through many military victories. But in 1814, a group of European countries defeated him in the War of the Sixth Coalition. This ended Napoleon's empire and brought the royal family back to power.

The Bourbon Restoration officially began around April 6, 1814. It lasted until the July Revolution in 1830. There was a short break in spring 1815, called the "Hundred Days". During this time, Napoleon escaped and returned, forcing the Bourbons to flee France. But after Napoleon was defeated again by the Seventh Coalition, the Bourbons came back to power in July.

At the Congress of Vienna, a big meeting where European powers decided on peace terms, the Bourbons were treated with respect. However, they had to give up almost all the land France had gained during the Revolution and Napoleon's rule since 1789.

France's New Government: A Constitutional Monarchy

Unlike the old absolute monarchy, where the king had all the power, the Bourbon Restoration brought a constitutional monarchy. This meant the king's power had some limits. The new king, Louis XVIII, accepted most of the changes that had happened in France between 1792 and 1814. His main goal was to keep things stable. He didn't try to take back land or property that had been taken from royal supporters who had left France.

The period was mostly conservative, meaning it favored traditional ways. There were some small but ongoing protests. However, the government was quite stable until Charles X became king. The Catholic Church also became very powerful in French politics again. During the Bourbon Restoration, France enjoyed a time of economic growth and the start of industrialization.

Big Changes That Stayed in France

The French Revolution and Napoleon's time brought huge changes to France. The Bourbon Restoration didn't reverse most of them.

- Centralized Power: France became very centralized. All important decisions were made in Paris. The country was divided into more than 80 départements (like states or provinces), which still exist today. Each department had the same government structure and was controlled by a leader appointed by Paris.

- New Laws: The old confusing legal systems were gone. Now, there was one standard set of laws, the Napoleonic Code. Judges were appointed by Paris, and the police were controlled by the national government.

- The Church and Land: The Revolutionary governments had taken all the land and buildings belonging to the Catholic Church. These were sold to many middle-class buyers. It was impossible for the new kings to give them back. Bishops still led their church areas (called dioceses), which matched the new department borders. They communicated with the pope through the government in Paris. Priests, nuns, and other religious people were paid by the state.

- Education: Public education was also centralized. A "Grand Master" in Paris controlled every part of the national education system. New technical universities were opened in Paris. These schools are still important today for training future leaders.

- New Elites: The conservative group was split. There were the old noble families who had returned, and the new wealthy people who had become important under Napoleon. The old nobles wanted their land back but didn't feel loyal to the new government. The new elite made fun of the old group, calling them outdated. Both groups feared social disorder, but they didn't trust each other enough to work together.

- Peasants and Workers: The old aristocracy had lost their special rights over farmland. Peasants were no longer under their control. Many peasants eagerly bought land, often taking out loans to do so. City workers were a small group, freed from old rules set by medieval guilds. However, France was slow to industrialize, so much work was still done by hand.

- National Identity: France was still divided by local customs and languages. But a new sense of French nationalism began to grow, focusing national pride on the Army and foreign affairs.

Political Scene During the Restoration

In April 1814, the armies that defeated Napoleon brought Louis XVIII of France back to the throne. He was the brother of the executed King Louis XVI. A new set of rules for the government, called the Charter of 1814, was created. It said all French people were equal before the law. However, the king and nobles still had a lot of power. Only men who paid a certain amount in taxes could vote, which was a very small number of people.

The king was the most powerful person in the state. He controlled the army and navy, declared war, made peace treaties, appointed all government officials, and made rules to carry out laws and keep the country safe. Louis XVIII was fairly open-minded and chose many moderate government leaders.

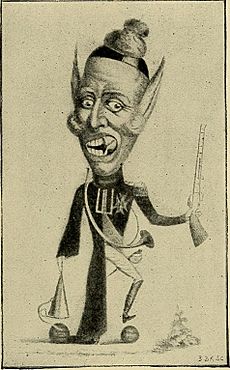

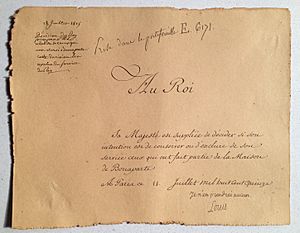

Louis XVIII died in September 1824. His brother, Charles X, became the new king. Charles X was much more conservative than Louis. He passed stricter laws, like the Anti-Sacrilege Act (1825–1830). Because people resisted and showed disrespect, the king and his ministers tried to control the 1830 election through special orders called the July Ordinances. This caused a revolution in Paris. Charles gave up his throne, and on August 9, 1830, the Chamber of Deputies declared Louis Phillipe d'Orleans the new King of the French. This began the July Monarchy.

Louis XVIII's Reign (1814–1824)

The First Restoration (1814)

Louis XVIII became king in 1814 largely thanks to Talleyrand. Talleyrand was Napoleon's former foreign minister. He convinced the winning Allied Powers that bringing the Bourbons back was a good idea. The Allies weren't sure who should be king at first. Britain wanted the Bourbons, Austria thought about Napoleon's son, and Russia was open to other options. Napoleon was offered to keep the throne in February 1814 if France returned to its 1792 borders, but he said no. The idea of restoring the monarchy seemed risky. However, the French people were tired of war and wanted peace. Also, there were demonstrations supporting the Bourbons in cities like Paris and Bordeaux, which helped convince the Allies.

Louis XVIII agreed to a written constitution called the Charter of 1814. This Charter set up a two-house parliament: a Chamber of Peers (whose members inherited their positions or were appointed) and an elected Chamber of Deputies. Their role was to advise the king, except on taxes. Only the king could suggest or approve laws, and appoint or remove ministers. Very few people could vote, only about 1% of men who owned a lot of property. Many of the legal, administrative, and economic changes from the Revolution were kept. The Napoleonic Code, which guaranteed legal equality, and the new system of dividing the country into départments were not changed.

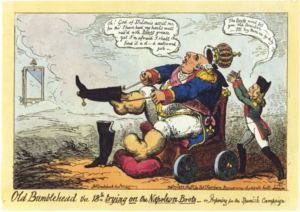

At first, Louis was popular. But his attempts to undo some results of the French Revolution quickly made him lose support. For example, he replaced the tricolore flag with the white flag. He called himself "Louis XVIII" (as if Louis XVII had actually ruled) and "King of France" instead of "King of the French." He also recognized the anniversaries of the deaths of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. More seriously, the Catholic Church and returning nobles tried to get back their old lands that had been taken during the Revolution. The army, non-Catholics, and workers affected by a post-war economic slowdown also disliked Louis.

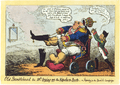

The Hundred Days (1815)

Napoleon heard about the unhappiness in France. On March 20, 1815, he returned to Paris from Elba. As he marched, most soldiers sent to stop him, even those who were supposed to be loyal to the king, chose to join Napoleon instead. Louis XVIII fled from Paris to Ghent on March 19.

After Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and sent away again, Louis XVIII returned. During his absence, there was a small revolt in a pro-royalist area called Vendée, but it was stopped. There weren't many other acts against the monarchy, even though Napoleon's popularity was starting to fade.

The Second Restoration (1815)

Talleyrand was again important in bringing the Bourbons back to power. So was Joseph Fouché, Napoleon's police minister. This Second Restoration began with the Second White Terror. This was a time, mostly in the south of France, when unofficial groups supporting the monarchy sought revenge against those who had helped Napoleon. About 200–300 people were killed, and thousands fled. Around 70,000 government officials were fired. The pro-Bourbon attackers were often called Verdets because of their green ribbons, the color of the comte d'Artois (who later became Charles X). After a period of violence, the King and his ministers sent officials to restore order.

A new Treaty of Paris was signed on November 20, 1815. It was stricter than the 1814 treaty. France had to pay 700 million francs in damages. The country's borders were reduced to their 1790 size, not 1792 as in the earlier treaty. Until 1818, France was occupied by 1.2 million foreign soldiers, and France had to pay for their housing and food, on top of the damages. The promise of tax cuts from 1814 couldn't happen because of these payments. These events, along with the White Terror, created strong opposition for Louis XVIII.

Louis's main ministers were moderate at first, like Talleyrand and the Duc de Richelieu. Louis himself followed a careful policy. The parliament elected in 1815, called the chambre introuvable (meaning "unobtainable" by Louis because it was so extremely royalist), was dominated by ultra-royalists. They quickly became known for being "more royalist than the king." This parliament removed the Talleyrand-Fouché government. It tried to make the White Terror legal, judging enemies of the state, firing many civil servants, and dismissing army officers. Richelieu, who had left France in 1789, became Prime Minister. The ultra-royalist parliament continued to strongly support the monarchy and the church.

In September 1816, Louis dissolved the parliament because of its extreme actions. New elections in 1816 resulted in a more liberal parliament. Richelieu served until 1818, followed by other ministers. This was a time when a group called the Doctrinaires influenced policy. They hoped to combine the monarchy with the ideas of the French Revolution. The government changed election laws to allow some rich business people to vote, trying to prevent the ultra-royalists from winning too many seats. Press censorship was eased, and some military positions were opened to competition. New schools were set up, challenging the Catholic Church's control over primary education.

By 1820, the liberal opposition in parliament became difficult to manage. The assassination of the Duc de Berry (the son of Louis's brother and future king Charles X) in February 1820 led to the fall of the moderate government and the rise of the ultra-royalists.

Richelieu returned to power for a short time (1820-1821). The press was censored more strictly, and people could be detained without trial again. After a big victory in the November 1820 election, a new ultra-royalist government was formed, led by Jean-Baptiste de Villèle. The ultra-royalists were back in power at a good time: Berry's wife gave birth to a "miracle child," Henri, after his death. Napoleon died in 1821, and his son was held in Austria. Famous writers like Chateaubriand supported the ultra-royalists. However, Villèle proved to be cautious, and as long as Louis XVIII was alive, very extreme policies were kept to a minimum.

The ultra-royalists gained more support. In 1823, France intervened in Spain to support the Spanish Bourbon King Ferdinand VII against the liberal Spanish government. This action, called the Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, made many French people feel patriotic. French troops marched to Madrid and Cádiz, easily removing the liberals. This intervention was seen as a way to regain influence in Spain. Support for the ultra-royalists grew, and they won another large majority in the 1824 election.

Louis XVIII died on September 16, 1824. His brother, the Comte d'Artois, became king as Charles X.

Charles X's Reign (1824–1830)

A More Conservative Turn (1824–1830)

When Charles X became king, the ultra-royalists, whom he led, were already in control of the parliament. So, the government led by comte de Villèle continued. The careful approach that Louis XVIII had used with the ultra-royalists was now gone.

After the Revolution, there was a renewed interest in Christianity in France. The ultra-royalists worked to make the Catholic Church powerful again. In 1825, they passed the Anti-Sacrilege Act, which made stealing consecrated religious items punishable by death. This law caused a lot of anger, even though it was mostly symbolic and not really enforced. More controversial was the return of the Jesuits, a Catholic order. They set up schools for elite youth outside the official university system. The Jesuits were very loyal to the Pope, which many people disliked. The king ended their official role in 1828.

New laws were passed to pay money to royalists whose lands had been taken during the Revolution. This law, called le milliard des émigrés, set aside 988 million francs for compensation. This was paid for by government bonds. Surprisingly, this law also helped the one million owners of the old confiscated lands, as their property rights were now confirmed, making their land more valuable.

In 1826, Villèle tried to bring back the law of primogeniture, which meant the oldest son would inherit all the family's land. This was for large estates. Liberals and the press, along with some royalists like Chateaubriand, strongly opposed this. Their loud criticism made the government try to pass a law to restrict the press in December. This only made the opposition angrier, and the bill was withdrawn.

The Villèle government faced growing pressure from liberal newspapers. Chateaubriand wrote articles criticizing the government. Other groups formed to oppose press censorship and work within the law to support liberal candidates in elections.

In April 1827, the King and Villèle faced an unruly National Guard. During a review, soldiers shouted anti-Jesuit remarks at the king's niece. Villèle faced even worse treatment. In response, the Guard was disbanded. Pamphlets continued to spread, accusing Charles of working with the Pope and planning to bring back old taxes.

By the 1827 election, moderate royalists and the business community also began to turn against Charles. A financial crisis in 1825, which they blamed on the government, contributed to this. Writers like Victor Hugo also started to criticize the government. Opposition groups worked hard to register as many voters as possible, countering government efforts to remove some voters.

The new parliament didn't have a clear majority for any side. Villèle's successor, the vicomte de Martignac, tried to find a middle ground. He eased press controls, expelled Jesuits, and limited Catholic schools. Charles, however, was unhappy with this new government. He surrounded himself with extreme royalists. Martignac was removed when his government lost a vote on local government. Charles chose Polignac as his chief minister in November 1829. Polignac was disliked by liberals and even by Chateaubriand. This political stalemate led some royalists to call for a coup (a sudden takeover of power), and prominent liberals called for a tax strike.

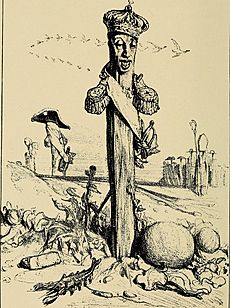

In March 1830, the King gave a speech that hinted at threats to the opposition. In response, 221 members of parliament (a majority) condemned the government. Charles then suspended and later dissolved parliament. Charles believed he was popular with the common people, who couldn't vote. He and Polignac decided to pursue an ambitious foreign policy of taking over new lands. France had already intervened in the Mediterranean. Now, expeditions were sent to Greece and Madagascar. Polignac also started the French conquest of Algeria. Victory was announced in early July. However, foreign policy wasn't enough to distract from problems at home.

Charles's decision to dissolve parliament, his "July Ordinances" (which strictly controlled the press), and his limits on voting rights led to the July Revolution of 1830. The main reason for the government's fall was that, while it kept the support of the nobles, the Catholic Church, and many peasants, the ultra-royalist cause was very unpopular outside of parliament. This was especially true for industrial workers and the middle class. A big reason for this was a sharp rise in food prices from 1827–1830, caused by bad harvests. Workers struggled greatly and were angry that the government didn't seem to care about their urgent needs.

Charles gave up his throne in favor of his grandson, the Comte de Chambord. He then left for England. However, the liberal-controlled parliament refused to accept the Comte de Chambord as Henry V. In a vote mostly boycotted by conservative members, the parliament declared the French throne empty. On August 9, they made Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the new king. This began the July Monarchy.

Tensions Leading to Revolution (1827–1830)

Historians still debate the exact reasons for Charles X's downfall. However, it's generally agreed that between 1820 and 1830, economic problems combined with a growing liberal opposition in parliament eventually brought down the conservative Bourbons.

From 1827 to 1830, France faced an economic slowdown in both industry and farming. Several bad grain harvests in the late 1820s pushed up the prices of basic foods. Farmers wanted the government to lower taxes on imported grain to reduce prices and help their situation. However, Charles X, influenced by wealthy landowners, kept the taxes in place. He did this because Louis XVIII had lowered taxes during famines in 1816, which angered wealthy landowners who were important supporters of the monarchy. So, from 1827 to 1830, peasants faced economic hardship and rising prices.

At the same time, international pressures and less buying power from rural areas led to less economic activity in cities. This industrial slowdown contributed to rising poverty among Parisian workers. By 1830, many different groups of people were suffering from Charles X's economic policies.

While the French economy struggled, a series of elections brought a strong liberal group into parliament. This liberal majority grew more and more unhappy with the policies of the moderate Martignac and the ultra-royalist Polignac. They wanted to protect the limited freedoms of the Charter of 1814. They also wanted more people to be able to vote and more liberal economic policies. They demanded the right, as the majority group, to choose the Prime Minister and the government leaders.

Also, as the liberal group grew in parliament, a liberal press grew in France, mainly in Paris. These newspapers offered a different view from the government's news and conservative papers. They became very important in sharing political opinions with the Parisian public. They were a key link between the rising liberals and the increasingly angry and struggling French people.

By 1830, Charles X's government faced problems from all sides. The new liberal majority clearly wouldn't give in to Polignac's strict policies. The growth of a liberal press in Paris, which sold more copies than the official government newspaper, showed a shift in Parisian politics towards more liberal ideas. Yet, Charles's main support came from the right side of politics, and his own views were conservative. He simply couldn't give in to the growing demands from parliament. The situation was about to reach a breaking point.

The July Revolution (1830)

The Charter of 1814 had made France a constitutional monarchy. While the king had a lot of power over making policies and was the head of the government, he still needed parliament to approve his laws. The Charter also set rules for how members of parliament were elected and their rights. So, in 1830, Charles X faced a big problem. He couldn't go beyond his constitutional limits, but he also couldn't carry out his policies with a liberal majority in parliament. He decided to take strong action after parliament voted against his government in March 1830. He decided to change the Charter of 1814 by special orders. These orders, known as the "Four Ordinances," dissolved parliament, stopped freedom of the press, prevented the more liberal middle class from voting in future elections, and called for new elections.

People were outraged. On July 10, 1830, even before the king made his announcements, a group of wealthy, liberal journalists and newspaper owners, led by Adolphe Thiers, met in Paris. They decided that if Charles made his expected announcements, the Parisian journalists would publish strong criticisms of the king's actions to get the public to act. So, when Charles X made his announcements on July 25, 1830, the liberal newspapers published articles and complaints criticizing the king's unfair actions.

The crowds in Paris also took action. Driven by patriotism and economic hardship, they built barricades and attacked government buildings. Within days, the situation got out of the monarchy's control. As the government tried to shut down liberal newspapers, the people defended them. They also attacked pro-Bourbon presses and stopped the monarchy's ability to enforce its will. Seeing this chance, the liberals in parliament began writing resolutions and complaints against the king. The king finally gave up his throne on July 30, 1830. Twenty minutes later, his son, Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême, who had briefly become Louis XIX, also gave up his throne. The crown then technically passed to Charles X's grandson, who would have been Henry V. However, the newly powerful parliament declared the throne empty. On August 9, they made Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the new king. This marked the start of the July Monarchy.

Louis-Philippe and the Orléans Family

Louis-Philippe became king because of the July Revolution of 1830. He ruled not as "King of France" but as "King of the French." This showed a shift towards the idea that the people, not just the king, held power. The Orléanist family stayed in power until 1848. After the last king to rule France was removed during the February 1848 Revolution, the French Second Republic was formed. Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was elected as President (1848–1852). In 1851, Napoleon declared himself Emperor Napoleon III of the Second Empire, which lasted from 1852 to 1870.

Political Groups During the Restoration

Political groups changed a lot during the Restoration. The parliament often switched between periods of strict ultra-royalist rule and more open liberal rule. The harshness of the White Terror pushed opponents of the monarchy out of politics. However, influential people with different ideas for France's constitutional monarchy still argued.

All groups were afraid of the common people, who couldn't vote. Their political goals were focused on favoring certain classes. Changes in parliament happened because the majority group would go too far, leading to the parliament being dissolved and a new majority forming. Important events, like the assassination of the Duc de Berry in 1820, also caused shifts.

The main arguments were power struggles between the powerful (the king against parliament members), rather than fights between the monarchy and the common people. Even though parliament members claimed to defend the people's interests, most were very afraid of common people, new ideas, and even simple changes like allowing more people to vote.

Here are the main political groups during the Restoration:

Ultra-royalists

The Ultra-royalists wanted to go back to the Ancien Régime, the old system that existed before 1789. This meant an absolute monarchy (where the king had total power), control by the nobility, and politics being only for "devoted Christians." They were against republics and against democracy. They believed in "Government on High," meaning power should come from above. While they accepted a limited form of democracy where only wealthy people could vote, they felt the Charter of 1814 was too revolutionary. They wanted to bring back old privileges, give the Catholic Church a major political role, and have a king who was actively involved in politics, not just a figurehead, like Charles X.

Important ultra-royalist thinkers were Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre. Their leaders in parliament included François Régis de La Bourdonnaye and, in 1829, Jules de Polignac. Their main newspapers were La Quotidienne and La Gazette, along with the Drapeau Blanc (named after the Bourbon white flag) and the Oriflamme.

Doctrinaires

The Doctrinaires were mostly wealthy and educated middle-class men. They were lawyers, high-ranking officials from Napoleon's time, and university professors. They feared the nobility becoming too powerful, as much as they feared the democrats. They accepted the Royal Charter because it guaranteed freedom and equality for citizens. However, they believed it also kept the "ignorant masses" in check. They were classical liberals and were in the center-right of the Restoration's political groups. They supported both capitalism and Catholicism. They tried to combine a parliament (where only wealthy people voted) with a monarchy (where the king had a symbolic role). They rejected the absolute power and clericalism (church influence) of the Ultra-Royalists, as well as the idea of everyone voting, which was supported by the liberal left and republicans. Important figures were Pierre Paul Royer-Collard, François Guizot, and the count of Serre. Their newspapers were Le Courrier français and Le Censeur.

Liberal Left

The Liberals were mostly from the petite-bourgeoisie (small business owners and professionals). They included doctors, lawyers, and in rural areas, merchants. They benefited from the slow growth of a new middle-class elite as the Industrial Revolution began.

Some of them accepted the idea of a monarchy, but only if it was strictly symbolic and parliament had the real power. Others were moderate republicans. Beyond government structure, they agreed on wanting to bring back the democratic ideas of the French Revolution. This included reducing the power of the church and nobles. They felt the constitutional Charter wasn't democratic enough. They disliked the peace treaties of 1815, the White Terror, and the return of the clergy and nobility to power. They wanted to lower the amount of taxes needed to vote, to include more of the middle class, and eventually supported universal suffrage (everyone voting) or at least a much wider voting system for ordinary middle-class people like farmers and craftspeople. Important figures were the parliamentary monarchist Benjamin Constant, the army officer Maximilien Sebastien Foy, the republican lawyer Jacques-Antoine Manuel, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Their newspapers were La Minerve, Le Constitutionnel, and Le Globe.

Republicans and Socialists

The only active Republicans were on the left to far-left, mainly among workers. Workers had no vote and their voices weren't heard. Their protests were stopped or ignored. For some, like Blanqui, revolution seemed to be the only way to make changes. Garnier-Pagès, and Louis-Eugène and Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac considered themselves Republicans. Cabet and Raspail were active as socialists. Saint-Simon was also active during this time and even appealed directly to Louis XVIII before his death in 1824.

Religion in France

By 1800, the Catholic Church was poor, damaged, and disorganized. Its clergy (priests and religious leaders) were few and old. Younger people had received little religious education and weren't familiar with traditional worship. However, because of the stress of foreign wars, religious devotion was strong, especially among women. Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 brought stability and stopped attacks on the Church.

With the Restoration, the Catholic Church again became the official state religion. The government supported it financially and politically. The Church's lands and money were not returned, but the government paid salaries and covered costs for normal church activities. Bishops regained control of Catholic affairs. Before the Revolution, the nobility wasn't very religious. But decades of exile created a strong alliance between the monarchy and the Church. The royalists who returned were much more devout and knew they needed a close alliance with the Church. They had given up their doubts and now promoted a wave of Catholic religious feeling that was spreading across Europe. This included a new respect for the Virgin Mary, saints, and popular religious practices like praying the rosary. Religious devotion was much stronger and more visible in rural areas than in Paris and other cities. France had about 32 million people, including about 680,000 Protestants and 60,000 Jews, who were allowed to practice their religions. The anti-clerical ideas of the Enlightenment had not disappeared, but they were less obvious.

Among educated people, there was a big change in thinking from classical ideas to passionate romanticism. A book from 1802 by François-René de Chateaubriand called Génie du christianisme ("The Genius of Christianity") greatly influenced French literature and intellectual life. It stressed how important religion was in creating European culture. Chateaubriand's book "did more than any other single work to restore the credibility and prestige of Christianity in intellectual circles and launched a fashionable rediscovery of the Middle Ages and their Christian civilisation." This religious revival wasn't just for educated people; it was also seen in the real, though uneven, re-Christianization of the French countryside.

Economy During the Restoration

When the Bourbons returned in 1814, the traditional aristocracy, who didn't value business, came back to power. British goods flooded the French market. France responded by putting high taxes (tariffs) on imports to protect its own businesses, especially small-scale manufacturing like textiles. The tariff on iron goods reached 120%. Farming had never needed protection before, but now demanded it because imported foods, like Russian grain, were cheaper. French winemakers strongly supported tariffs. Their wines didn't need protection, but they insisted on high tariffs on imported tea. One farmer in parliament explained: "Tea breaks down our national character by converting those who use it often into cold and stuffy Nordic types, while wine arouses in the soul that gentle gaiety that gives Frenchmen their amiable and witty national character." The French government made up official statistics to claim that exports and imports were growing. In reality, there was stagnation. The economic crisis of 1826-29 disappointed the business community and made them ready to support the revolution in 1830.

Art and Literature of the Time

Romanticism greatly changed art and literature during this period. It helped create a large new audience from the middle class. Some of the most famous works from this time include:

- Les Misérables, a novel by Victor Hugo that takes place in the 20 years after Napoleon's Hundred Days.

- The Red and the Black, a novel by Stendhal set in the final years of the Bourbon Restoration.

- La Comédie humaine, a series of almost 100 novels and plays by Honoré de Balzac, set during the Restoration and the July Monarchy.

Paris During the Restoration

Paris slowly grew in population from 714,000 people in 1817 to 786,000 in 1831. During this time, Parisians saw the first public transport system, the first gas street lights, and the first uniformed Paris police officers. In July 1830, a popular uprising in the streets of Paris brought down the Bourbon monarchy.

How History Views the Restoration

After two decades of war and revolution, the Restoration brought peace, quiet, and general prosperity. Historian Gordon Wright says, "Frenchmen were, on the whole, well governed, prosperous, contented during the 15-year period; one historian even describes the restoration era as 'one of the happiest periods in [France's] history.'"

France had recovered from the stress, disorganization, wars, killings, and horrors of two decades of disruption. It was peaceful throughout this time. France paid a large war debt to the winners but managed to do so without much trouble. The occupying soldiers left peacefully. France's population grew by three million, and the economy was strong from 1815 to 1825. The economic downturn of 1825 was caused by bad harvests. The national credit was strong, public wealth increased significantly, and the national budget had a surplus every year. In the private sector, banking grew dramatically, making Paris a world financial center, along with London. The Rothschild family became world-famous, with the French branch led by James Mayer de Rothschild (1792–1868). The transportation system improved, with better roads, longer canals, and common steamboat traffic. Industrialization was slower compared to Britain and Belgium. The railway system hadn't appeared yet. Industry was heavily protected by tariffs, so there wasn't much demand for new businesses or ideas.

Culture thrived with new romantic ideas. Public speaking was highly valued, and sophisticated debates were common. Châteaubriand and Madame de Stael (1766-1817) were famous across Europe for their new romantic literature. Madame de Staël made important contributions to understanding society and literature. History writing flourished; François Guizot, Benjamin Constant, and Madame de Staël learned from the past to guide the future. The paintings of Eugène Delacroix set the standards for romantic art. Music, theater, science, and philosophy all thrived. Higher education flourished at the Sorbonne. Important new institutions gave France world leadership in many advanced fields. Examples include the École Nationale des Chartes (1821) for studying history, the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in 1829 for innovative engineering, and the École des Beaux-Arts for fine arts, which was re-established in 1830.

Charles X often made internal tensions worse and tried to stop his opponents with harsh measures. These failed completely and forced him into exile for the third time. However, the government's handling of foreign affairs was a success. France kept a low profile, and Europe forgot its past disagreements. Louis and Charles had little interest in foreign affairs, so France played only small roles. For example, it helped other powers deal with Greece and Turkey. Charles X wrongly thought that success abroad would make up for problems at home. So, he made a huge effort to conquer Algiers in 1830. He sent a massive force of 38,000 soldiers and 4,500 horses on 103 warships and 469 merchant ships. The expedition was a big military success. It even paid for itself with captured treasures. This event started the second French colonial empire, but it didn't give the King the political support he desperately needed at home.

The Restoration in Recent Pop Culture

The 2007 French historical film Jacquou le Croquant, directed by Laurent Boutonnat and starring Gaspard Ulliel and Marie-Josée Croze, is based on the Bourbon Restoration period.

See also

- French Restoration style

- Pierre Louis Jean Casimir de Blacas

- Mathieu de Montmorency

- French Empire mantel clock

- French monarchs family tree

- France in the long nineteenth century

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |