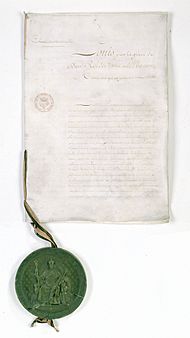

Charter of 1814 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Charter of 1814 |

|

|

The French Charter of 1814 was an important document given by King Louis XVIII of France. This happened right after the Bourbon family returned to power in France. It was like a set of rules for how the country would be governed.

The Congress of Vienna, a big meeting of European leaders, said that King Louis XVIII needed to create some kind of constitution before he could become king again. At first, he didn't like the constitution suggested by the government at the time. So, on July 4, 1814, he gave France his own set of rules, called the Charter. Once he did this, he was officially crowned King Louis XVIII, and the monarchy was back.

The Charter was a way to find a middle ground. It kept many of the good changes from the French Revolution and the time of the French Empire. But it also brought back the Bourbon royal family. The name "constitutional Charter" shows this mix. "Charter" reminded people of the old ways before the Revolution, while "constitutional" showed it had new, revolutionary ideas. However, it created a limited monarchy, meaning the King still had a lot of power and was the main leader of the country.

Contents

What Was the Charter of 1814?

The Charter of 1814 was a document that explained the jobs and powers of the different parts of the French government. This included the King and the two groups of lawmakers, called chambers.

It wasn't meant to be a completely new basic law for France. Instead, it was more about changing how the government worked. It replaced the old "Estates General" and "Parliaments" with two new chambers. It also set out what these new chambers could do.

Who Wrote the Charter?

King Louis XVIII set up a special group to write the Charter on May 18, 1814. He chose twenty-two people for this committee. He didn't include some important figures like Talleyrand, even though Talleyrand had helped with an earlier constitution idea.

The committee was led by Charles Dambray, who was a high-ranking official. It included:

- Three special representatives from the King.

- Nine members from the "Conservative Senate," an important government body.

- Nine members from the "Legislative Body," another group of lawmakers.

This group had its first meeting on May 22 and worked for six days. By May 26, they had a draft ready, which the King's private advisors approved.

Rights for the French People

The first twelve articles of the Charter were like a "Bill of Rights" for the French people. They included important ideas such as:

- Everyone was equal before the law.

- People had rights to fair legal processes.

- People could practice their own religion.

- There was freedom of the press (though this was later limited).

- Private property was protected.

- People no longer had to join the army by force (conscription was ended).

These ideas, along with keeping the Napoleonic Code (a set of laws created by Napoleon), were big achievements from the French Revolution.

However, it was up to the lawmakers, not the courts, to protect these rights. Also, while there was religious freedom, the Catholic Church was named the official state religion.

Main Points of the Charter

The Charter covered many important areas of how France would be run:

- Individual Rights: It protected personal rights, property, freedom of the press, and religious freedom. However, Catholicism was declared the official state religion.

- Military Service: The forced joining of the army (conscription) was stopped.

- Property: The sale of national goods from the Revolution was not changed. Only remaining goods were given back to people who had left France during the Revolution.

- King's Power: The King had executive power. This meant he could decide on peace and war, make alliances, and appoint officials. He could also make laws by special orders for the country's security. He was the head of the armies. The King started and approved laws. He appointed ministers, who reported only to him.

- Lawmaking Power: The power to make laws was shared between the King and two chambers.

- The Chamber of Peers was made up of nobles chosen by the King. They served for life, and their positions could be passed down.

- The Chamber of Deputies was elected. However, only wealthy men who paid a lot in taxes could vote or be elected. The King could also dissolve this chamber and call for new elections.

- Judicial Power: Judges were appointed by the King and could not be removed easily. The system of juries was kept. The King still had a lot of power over the courts.

- Nobility: The old noble titles from before the Revolution were brought back. Noble titles from the Empire (under Napoleon) were also kept. Being a noble did not mean you were free from the duties of society.

- Voting Rights: Only men aged 30 or older who paid a certain amount in direct taxes could vote. Even fewer, older men who paid even more taxes could be elected. This meant only a small number of wealthy men could participate in politics.

- Administration: The ways the country was managed by the Revolution and Empire were mostly kept. Power was kept very centralized, meaning the government or state representatives appointed local officials.

The King and His Ministers

The King was at the very center of power under the Charter of 1814.

The Charter said the King was the Head of State and the chief executive. This meant he:

- Appointed public officials.

- Issued rules needed to carry out laws and keep the country safe.

- Commanded the army and navy.

- Declared war.

- Made peace treaties and alliances with other countries.

The King also had a lot of say in making laws. He was the only one who could suggest new laws to the Parliament. He also had the right to approve or reject laws passed by Parliament. The King could call Parliament together or send them home. He could even dissolve the Chamber of Deputies and call for new elections. He also chose the members of the House of Peers.

In the legal system, the King appointed judges and had the power to pardon people.

The Two Chambers

Like the British system, the Charter of 1814 created a two-part legislature. This included a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Peers.

The Chamber of Deputies was elected, but only by people who paid a lot of taxes. Voting happened in two steps. Voters chose members of "Electoral Colleges," and these colleges then elected the Deputies. To be in an Electoral College, you had to pay 300 francs a year in direct taxes. To be a Deputy, you had to pay 1000 francs a year. Since taxes were mostly on land, this meant only a very small group of the richest landowners could be Deputies. The King also appointed the leaders of the Electoral Colleges, which gave the government influence over elections.

The King appointed the members of the Chamber of Peers. These could be nobles who inherited their titles or people given titles for their public service. There was no limit to how many peers the King could appoint. This meant the King could always add more members. Besides making laws, the Chamber of Peers also acted as a special court. They could try officials who were accused of serious crimes or attacks against the state.

Members of both Chambers had special protections, like not being arrested easily. The King chose the leader of the Chamber of Deputies from a list of five members. The Chancellor of France, an official appointed by the King, led the Chamber of Peers.

Both Chambers had to agree for a law to pass. New laws could be started by the King in either Chamber. However, laws about taxes had to start in the Chamber of Deputies.

A Constitutional, Not Parliamentary, Monarchy

The King's powers were mostly carried out by his Ministers. The King chose these Ministers. The Charter said that "Ministers are responsible," but it wasn't very clear what this meant. It mainly meant they could be charged with serious crimes like treason. This responsibility could only be enforced by the Chamber of Deputies accusing them and the Chamber of Peers putting them on trial.

The Charter did not have the modern idea of parliamentary government. In a modern system, Ministers are responsible to the Parliament, not just the King. If Parliament loses trust in the Ministers, they can be removed without a trial.

This system was similar to other constitutional documents of that time. Even in Britain, the idea of Ministers being responsible to Parliament was based on tradition, not written law. So, the challenge for liberal politicians in France was to develop a system where:

- The King would only act on the advice of his Ministers.

- The Ministers, even though chosen by the King, would be leaders from the main group in Parliament.

- Ministers would have to resign if Parliament lost confidence in them.

Because only a few wealthy people could vote, and a very traditional group called the "Ultras" had a lot of power, these ideas didn't fully develop between 1814 and 1830. So, while the monarchy under the Charter had a constitution, it never became a truly parliamentary system of government.

How the Charter Could Be Changed

The Charter was presented as a gift from the King to the people. It wasn't seen as something the people created themselves. It ended with the words "Given at Paris, in the year of grace 1814, and of our reign the nineteenth." This meant King Louis XVIII considered his reign to have started in 1795, after the death of his nephew, Louis XVII. The King and future kings had to promise to uphold the Charter.

The Charter didn't have any rules for how it could be changed in the future. Some thought this meant it was a very basic law that everyone, including the King, had to follow. However, the July Revolution in 1830 showed that the Charter could be changed. It was then reissued in an updated form, showing it could be changed like any other law by the King and the Chambers working together.

Images for kids

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |