History of France facts for kids

The story of France begins a very long time ago, in the Iron Age. Back then, the land we now call France was mostly known as Gaul by the Romans. Ancient Greek writers described three main groups of people living there: the Gauls, the Aquitani, and the Belgae. The Gauls were the largest group. They were Celtic people and spoke a language called Gaulish.

Around 1000 BC, Greeks, Romans, and Carthaginians started building settlements along the Mediterranean coast. The Roman Republic took control of southern Gaul in the late 2nd century BC. Later, Julius Caesar and his Roman armies conquered the rest of Gaul in the Gallic Wars (58–51 BC). After this, a mix of Roman and Gaulish cultures grew, and Gaul became a big part of the Roman Empire.

As the Roman Empire weakened, Germanic tribes, especially the Franks, moved into Gaul. The Frankish king Clovis I united most of Gaul in the late 5th century. This set the stage for the Franks to rule the region for hundreds of years. Frankish power was strongest under Charlemagne. The Kingdom of France later grew out of the western part of Charlemagne's empire, called West Francia. It became more important under the House of Capet, started by Hugh Capet in 987.

A problem with who would be king next happened in 1328. This led to the Hundred Years' War between the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet. The war began in 1337 when Philip VI tried to take the Duchy of Aquitaine from Edward III of England. Edward also claimed the French throne. Even though the Plantagenets won early battles, like capturing John II of France, the Valois side eventually gained the upper hand. A famous hero from this war was Joan of Arc, a French peasant girl who led French forces against the English. The war ended with a Valois victory in 1453.

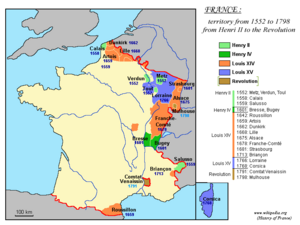

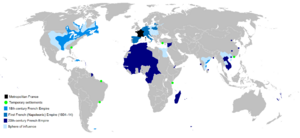

Winning the Hundred Years' War made French national pride stronger and greatly increased the power of the French kings. During the Ancien Régime (Old Rule) period, France became a powerful, centralized absolute monarchy. This happened through the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. During the French Wars of Religion, there was another crisis over who would be king. The last Valois king, Henry III, fought against the House of Bourbon and the House of Guise. Henry, the Bourbon King of Navarre, won and started the Bourbon family's rule. France also began building a worldwide colonial empire in the 16th century. The French king's power reached its peak under Louis XIV, known as "The Sun King."

In the late 1700s, the king and his system were overthrown in the French Revolution. France became a Republic for a while, until Napoleon Bonaparte created the French Empire. After Napoleon's defeat in the Napoleonic Wars, France had many changes in government. It was a monarchy, then a Second Republic, and then a Second Empire. Finally, a more stable French Third Republic was set up in 1870.

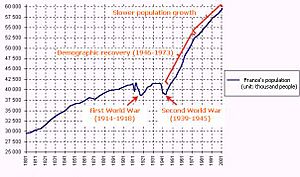

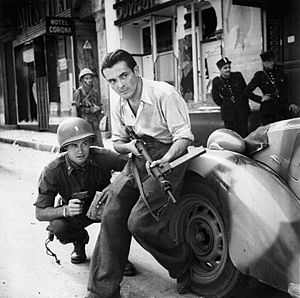

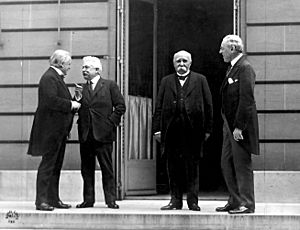

France was one of the Triple Entente powers in World War I against Germany. In World War II, France was one of the Allied Powers, but Nazi Germany conquered it in 1940. The Third Republic ended. Germany directly controlled most of the country, while the south was controlled by the Vichy government until 1942. Life was very hard, as Germany took food and people. Many Jewish people were killed. The Free France movement took over the colonial empire and led the Resistance during the war. After France was liberated in 1944, the Fourth Republic was created. France slowly recovered and had a baby boom. Long wars in Indochina and Algeria used up French resources and ended in defeat. After the 1958 Algerian Crisis, Charles de Gaulle started the French Fifth Republic. In the 1960s, most of the French colonial empire became independent. Smaller parts became overseas departments and collectivities of France. Since World War II, France has been a permanent member of the UN Security Council and NATO. It played a key role in creating the European Union. Even with slow economic growth recently, France is still a strong country in the 21st century.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Early People and Roman Rule

- Frankish Kingdoms: From Clovis to Charlemagne

- Building the Kingdom of France (987–1453)

- Early Modern France (1453–1789)

- Life in Early Modern France

- France Grows Stronger (15th and 16th Centuries)

- Religious Wars: Protestants and Catholics (1562–1629)

- Thirty Years' War (1618–1648)

- French Colonies (16th and 17th Centuries)

- Louis XIV: The Sun King (1643–1715)

- Changes in France and the World (1718–1783)

- The French Enlightenment

- Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

- Why the French Revolution Started

- The National Assembly and the Bastille (January – July 1789)

- Changes to the Church (October 1789 – December 1790)

- Creating a Constitutional Monarchy (June–September 1791)

- War and Uprisings (October 1791 – August 1792)

- Bloodshed and the Republic (September 1792)

- War and Civil War (November 1792 – Spring 1793)

- Political Showdown (May–June 1793)

- Counter-Revolution Suppressed (July 1793 – April 1794)

- Executing Politicians (February–July 1794)

- Ignoring the Working Classes (August 1794 – October 1795)

- Fighting Catholicism and Royalism (October 1795 – November 1799)

- Napoleonic France (1799–1815)

- The Long 19th Century (1815–1914)

- French Colonial Empire

- France in the World Wars (1914–1945)

- France Since 1945

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times: Early People and Roman Rule

Stone tools found in France show that early human ancestors might have lived there at least 1.6 million years ago. Neanderthals lived in Europe from about 400,000 BC but disappeared around 40,000 years ago. Modern humans, Homo sapiens, arrived in Europe about 43,000 years ago.

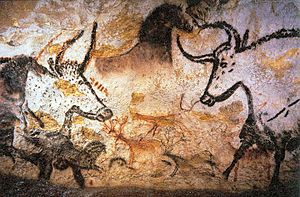

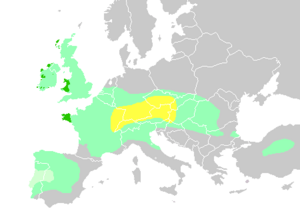

Ancient cave paintings in Gargas (around 25,000 BC) and Lascaux (around 15,000 BC) are examples of early human activity. Later, during the Neolithic period, people built the Carnac stones (around 4500 BC). The Iron Age saw the rise of the Hallstatt culture and then the La Tène culture. These were the last major cultures before the Romans expanded into Gaul.

Greek Settlements in Gaul

Around 600 BC, Greek people from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (today's Marseille) on the Mediterranean coast. This makes Marseille one of the oldest cities in France. Around the same time, some Celtic tribes arrived in the eastern parts of France. Their presence spread across the rest of France between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC.

The Gauls and Roman Conquest

Gaul covered large parts of modern France, Belgium, and Germany. It was home to many Celtic and Belgae tribes. The Romans called these people Gauls. They spoke the Gaulish language. Important cities like Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris) and Burdigala (Bordeaux) were founded by the Celts.

Long before the Romans, Greek sailors settled in what is now Provence. They founded important cities like Massalia (Marseille) and Nikaia (Nice). The Celts often fought with other tribes and with Germans. A Gaulish group led by Brennus even attacked Rome around 393 or 388 BC.

However, the Gauls' tribal society was not as organized as the Roman state. The Romans defeated the Gaulish tribes in battles like Sentinum and Telamon in the 3rd century BC. When Carthaginian commander Hannibal Barca fought the Romans, he hired many Gaulish fighters. This led to the Romans taking over Provence in 122 BC.

Later, Julius Caesar conquered all of Gaul. Despite strong Gaulish resistance led by Vercingetorix, the Gauls were defeated. They had some success at Gergovia, but were finally defeated at Alesia in 52 BC. The Romans then founded cities like Lugdunum (Lyon) and Narbonensis (Narbonne).

Roman Gaul: A New Culture

Gaul was divided into several Roman provinces. The Romans moved people around to prevent local groups from becoming a threat. Many Celts were moved or enslaved. Gaul saw a big cultural change under Roman rule. The Gaulish language was slowly replaced by Vulgar Latin. This was easier because Gaulish and Latin had some similarities. Gaul remained under Roman control for centuries, and Celtic culture gradually became Gallo-Roman culture.

Gauls became more integrated into the Roman Empire. Generals like Marcus Antonius Primus and Gnaeus Julius Agricola were born in Gaul, as were emperors Claudius and Caracalla. In 260 AD, Postumus created a short-lived Gallic Empire that included Gaul, Spain, and Britain. Germanic tribes, the Franks and the Alamanni, also entered Gaul around this time. The Gallic Empire ended in 274 AD.

In the 4th century, Celts from Britain, led by Conan Meriadoc, settled in Armorica. They spoke a language that later became Breton. In 418 AD, the Aquitanian province was given to the Goths to help fight the Vandals. These Goths had sacked Rome in 410 AD and set up their capital in Toulouse.

The Roman Empire struggled to deal with all the barbarian raids. Flavius Aëtius used different tribes against each other to keep some Roman control. He used the Huns against the Burgundians, forcing the Burgundians westward. The Burgundians were resettled near Lugdunum in 443 AD. The Huns, led by Attila, became a bigger threat. Aëtius then used the Visigoths against the Huns. The big battle was in 451 AD at Châlons, where Romans and Goths defeated Attila.

The Roman Empire was collapsing. Aquitania was given to the Visigoths, who soon took over much of southern Gaul and Spain. The Burgundians formed their own kingdom. Northern Gaul was left to the Franks. Besides the Germanic peoples, the Vascones entered Wasconia from the Pyrenees, and the Bretons formed three kingdoms in Armorica.

Frankish Kingdoms: From Clovis to Charlemagne

In 486 AD, Clovis I, leader of the Salian Franks, defeated Syagrius at Soissons. He then united most of northern and central Gaul under his rule. Clovis also won battles against other Germanic tribes like the Alamanni. In 496 AD, Clovis became Catholic. This gave him more power and support from his Christian subjects against the Arian Visigoths. He defeated Alaric II at Vouillé in 507 AD and added Aquitaine to his Frankish kingdom.

Clovis made Paris his capital and started the Merovingian dynasty. But his kingdom did not stay united after his death in 511 AD. According to Frankish traditions, all sons inherited part of the land. So, four kingdoms appeared, centered around Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims. Over time, the borders and number of Frankish kingdoms changed often. During this period, the Mayors of the Palace, who were originally the king's chief advisors, became the real rulers. The Merovingian kings became mostly figureheads.

By this time, Muslims had conquered Spain. Septimania became part of Al-Andalus, which threatened the Frankish kingdoms. Duke Odo the Great defeated a large invading force at Toulouse in 721 AD. However, he failed to stop a raiding party in 732 AD. The mayor of the palace, Charles Martel, defeated that raiding party at the Battle of Tours. This earned him great respect and power. In 751 AD, Pepin the Short (Charles Martel's son) became king, starting the Carolingian dynasty.

Carolingian power reached its peak under Pepin's son, Charlemagne. In 771 AD, Charlemagne reunited the Frankish lands. He then conquered the Lombards in northern Italy (774 AD), added Bavaria (788 AD), defeated the Avars (796 AD), pushed the border with Al-Andalus to Barcelona (801 AD), and took control of Lower Saxony (804 AD).

Because of his successes and support for the papacy, Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III in 800 AD. Charlemagne's son, Louis the Pious (ruled 814–840 AD), kept the empire united. However, this Carolingian Empire did not last after Louis I's death. Two of his sons, Charles the Bald and Louis the German, swore loyalty to each other against their brother, Lothair I, in the Oaths of Strasbourg. The empire was then divided among Louis's three sons in the Treaty of Verdun (843 AD). After a brief reunion (884–887 AD), the imperial title was no longer held in the western part, which became the basis for the future French kingdom.

Under the Carolingians, the kingdom was attacked by Viking raiders. Important figures like Count Odo of Paris and his brother King Robert became famous and even kings. This new family, called the Robertines, were the ancestors of the Capetian dynasty. Some Vikings, led by Rollo, settled in Normandy. King Charles the Simple gave them this land to protect against other raiders. The people who came from the mix of Viking leaders and the Franks and Gallo-Romans became known as the Normans.

Building the Kingdom of France (987–1453)

Powerful Local Rulers

France was very decentralized during the Middle Ages. The king's power was more about religion than administration. In the 11th century, local princes became very powerful. Regions like Normandy, Flanders, or Languedoc had power similar to kingdoms. The Capetians, who came from the Robertians, were powerful princes themselves. They had successfully replaced the weak Carolingian kings.

The Capetians held a dual role: King and Prince. As king, they held the Crown of Charlemagne. As Count of Paris, they held their personal lands, known as Île-de-France.

This dual status made their position complex. They were involved in power struggles within France as princes. But they also had religious authority over Roman Catholicism in France as King. The Capetian kings often treated other princes as enemies or allies, rather than as subjects. Their royal title was recognized but often ignored. In some remote areas, the king's authority was so weak that bandits were the real power.

Some of the king's vassals became very strong rulers in Western Europe. The Normans, Plantagenets, Lusignans, Hautevilles, Ramnulfids, and the House of Toulouse gained lands outside France. The most important conquest for French history was the Norman Conquest by William the Conqueror. After the Battle of Hastings, this linked England to France through Normandy. Even though the Normans were vassals of the French kings, they were also equals as kings of England. Their main political activity stayed in France.

Many French nobles also joined the crusades. French knights founded and ruled the Crusader states. An example of their legacy in the Middle East is the expansion of the Krak des Chevaliers by the Counts of Tripoli and Toulouse.

The Monarchy Grows Stronger

Over the next centuries, the French monarchy gained power over the strong barons. By the 16th century, they had absolute rule over France. Several things helped the French monarchy grow. The Capetian family ruled without interruption until 1328. Laws of primogeniture (eldest son inherits) made sure power passed smoothly. Also, the Capetians were seen as part of an old and famous royal family, making them socially superior to their rivals. Third, the Church supported the Capetians, favoring a strong central government in France. This alliance with the Church was a lasting legacy. The First Crusade was almost entirely made up of French princes. Over time, the King's power grew through conquests, seizures of land, and successful feudal battles.

The history of France as a kingdom truly begins with the election of Hugh Capet (940–996) in Reims in 987. Capet was "Duke of the Franks" and then became "King of the Franks." His lands were small, mostly around Paris. His lack of political importance helped him get elected by powerful barons. Many of his vassals (including the kings of England for a long time) ruled much larger territories than his own. He was recognized as king by many groups, including the Gauls, Bretons, Danes, Aquitanians, Goths, Spanish, and Gascons.

Count Borell of Barcelona asked Hugh for help against Islamic raids. But Hugh was busy fighting Charles of Lorraine. Other Spanish areas then became more independent. Hugh Capet, the first Capetian king, is not well-documented. His greatest achievement was surviving as king and defeating the Carolingian claimant. This allowed him to start what would become one of Europe's most powerful royal families.

Hugh's son, Robert the Pious, was crowned King of the Franks before his father died. Hugh Capet did this to secure his succession. Robert II met Emperor Henry II in 1023. They agreed to stop claiming each other's lands, setting a new stage for Capetian and Ottonian relations. Though a king with limited power, Robert II made significant efforts. His surviving documents show he relied heavily on the Church, like his father. He was known for his piety, even though he was excommunicated for living with a mistress. Robert II's reign was important for the Peace and Truce of God and the Cluniac Reforms.

Under King Philip I, the kingdom slowly recovered during his long reign (1060–1108). His reign also saw the start of the First Crusade to regain the Holy Land. His family was heavily involved, though he did not personally support it.

From Louis VI (ruled 1108–37) onward, royal authority became more accepted. Louis VI was more a soldier than a scholar. He raised money from his vassals in ways that made him unpopular. His attacks on his vassals, though damaging his image, strengthened royal power. From 1127, Louis had help from a skilled statesman, Abbot Suger. The abbot's advice was very valuable. Louis VI successfully defeated many robber barons. He often called his vassals to court. Those who didn't show up often had their lands taken and faced military campaigns. This policy clearly established royal authority around Paris. By Louis VI's death in 1137, Capetian authority was much stronger.

Thanks to Abbot Suger, King Louis VII (ruled 1137–80) had greater moral authority in France. Powerful vassals paid respect to the French king. Abbot Suger arranged Louis VII's marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1137. This made Louis VII Duke of Aquitaine and gave him much power. However, the couple disagreed over the burning of over a thousand people in Vitry.

King Louis VII was horrified by this and went to the Holy Land for forgiveness. He later involved France in the Second Crusade, but his relationship with Eleanor did not improve. Their marriage was annulled by the pope. Eleanor soon married Henry Fitzempress, Duke of Normandy, who became King of England two years later. Louis VII, once a powerful monarch, now faced a much stronger vassal. Henry was his equal as King of England and his strongest prince as Duke of Normandy and Aquitaine.

Abbot Suger's building ideas led to what is now known as Gothic architecture. This style became common for most European cathedrals built in the late Middle Ages.

Later Capetian Kings (1165–1328)

The later Capetian kings were much more powerful than the earlier ones. While Philip I could barely control his barons in Paris, Philip IV could influence popes and emperors. This period also saw complex international alliances and conflicts between the kings of France, England, and the Holy Roman Emperor.

Philip II Augustus Expands France

The reign of Philip II Augustus (ruled 1180–1223) was a key time for the French monarchy. His rule greatly expanded the French royal lands and influence. He set the stage for powerful kings like Saint Louis and Philip the Fair.

Philip II spent much of his reign fighting the Angevin Empire, which was a big threat to the King of France. Early in his reign, Philip II used Henry II of England's son against him. He allied with Richard Lionheart, Duke of Aquitaine and Henry II's son. Together, they attacked Henry's castle at Chinon and removed him from power.

Richard became King of England. The two kings then went on the Third Crusade. However, their alliance broke during the crusade. They fought each other in France, and Richard was close to defeating Philip II.

Besides their battles in France, the kings of France and England tried to put their allies in charge of the Holy Roman Empire. Philip II Augustus supported Philip of Swabia. Richard Lionheart supported Otto IV. Otto IV became the Holy Roman Emperor. The French crown was saved when Richard died from a wound he got fighting his own vassals.

John Lackland, Richard's successor, refused to come to the French court for a trial. Philip II then took John's lands in France, just as Louis VI had done to rebellious vassals. John's attempt to win back his French lands at the Battle of Bouvines (1214) failed completely. Philip II added Normandy and Anjou to his lands. He also captured the Counts of Boulogne and Flanders. Aquitaine and Gascony remained loyal to the English king. After the Battle of Bouvines, John's ally, Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV, was overthrown by Frederick II, who was Philip's ally. Philip II of France was very important in shaping politics in England and France.

Philip Augustus founded the Sorbonne and made Paris a city for scholars.

Prince Louis (the future Louis VIII, ruled 1223–26) was involved in the English civil war. This was because French and English nobles, once united, were now split. While French kings fought the Plantagenets, the Church called for the Albigensian Crusade. Southern France was then largely absorbed into the royal lands.

Saint Louis IX (1226–1270)

France truly became a centralized kingdom under Louis IX (ruled 1226–70). Saint Louis is often seen as a perfect example of faith and a good ruler. However, his reign was not perfect for everyone. He led unsuccessful crusades, and his growing government faced opposition. He also ordered the burning of Jewish books. Louis had a strong sense of justice and wanted to judge people himself.

Louis IX was only twelve when he became King of France. His mother, Blanche of Castile, was the real power as regent. Blanche's authority was strongly opposed by French barons, but she kept her position until Louis was old enough to rule.

In 1229, the King had to deal with a long strike at the University of Paris. The kingdom was vulnerable. War continued in the County of Toulouse, and the royal army was busy fighting resistance in Languedoc. Count Raymond VII of Toulouse finally signed the Treaty of Paris in 1229. He kept much of his land for life, but his daughter had no heir. So, the County of Toulouse went to the King of France.

King Henry III of England had not accepted the French king's rule over Aquitaine. He still hoped to get back Normandy and Anjou and rebuild the Angevin Empire. In 1230, he landed in Saint-Malo with a large force. Henry III's allies in Brittany and Normandy did not dare fight their own king, who led the counterattack himself. This led to the Saintonge War (1242).

Henry III was defeated and had to accept Louis IX's rule. Louis IX did not take Aquitaine from Henry III. Louis IX was now the most important landowner in France, in addition to being king. There was some opposition in Normandy, but it was easy to rule compared to Toulouse. The Conseil du Roi, which later became the Parlement, was founded during this time. After his conflict with King Henry III, Louis built a friendly relationship with the English king.

Saint Louis also supported new art forms like Gothic architecture. His Sainte-Chapelle became a famous Gothic building. He is also known for the Morgan Bible. France was involved in two crusades under Saint Louis: the Seventh Crusade and the Eighth Crusade. Both were failures for the French King.

Philip III and Philip IV (1270–1314)

Philip III became king when Saint Louis died in 1270 during the Eighth Crusade. Philip III was called "the Bold" because of his fighting skills, not his personality. Philip III took part in another failed crusade, the Aragonese Crusade, which cost him his life in 1285.

More government changes were made by Philip IV, also called Philip the Fair (ruled 1285–1314). This king was responsible for ending the Knights Templar. He signed the Auld Alliance and established the Parlement of Paris. Philip IV was so powerful that he could name popes and emperors. The papacy was moved to Avignon, and all popes at that time were French, like Philip IV's puppet Bertrand de Goth.

Early Valois Kings and the Hundred Years' War (1328–1453)

Tensions between the Plantagenet and Capet families exploded during the Hundred Years' War (1337 to 1453). The Plantagenets claimed the French throne from the Valois. This was also the time of the Black Death and several civil wars. The French people suffered greatly. In 1420, the Treaty of Troyes made Henry V heir to Charles VI. Henry V died before Charles, so Henry VI of England became king of both England and France.

Some say the hard times during the Hundred Years' War sparked French nationalism, led by Joan of Arc (1412–1431). The Hundred Years' War is remembered more as a war between France and England than as feudal struggles. During this war, France changed politically and militarily.

A French-Scottish army won at the Battle of Baugé (1421). But the defeats at Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415) made French nobles realize they needed an organized army, not just knights. Charles VII (ruled 1422–61) created the first French standing army. He defeated the Plantagenets at Patay (1429) and again, using cannons, at Formigny (1450). The Battle of Castillon (1453) was the last battle of this war. Only Calais and the Channel Islands remained under English rule.

Early Modern France (1453–1789)

Life in Early Modern France

France in the Ancien Régime was about 520,000 square kilometers. It had 13 million people in 1484 and 20 million in 1700. France had the second-largest population in Europe around 1700. This lead slowly faded after 1700 as other countries grew faster.

In 1500, people didn't really feel "French"; they felt more connected to their local areas. By 1600, however, people started calling themselves "good Frenchmen."

Power and Society

Political power was spread out. The law courts (Parlements) were powerful, especially in Paris. But the king had only about 10,000 officials for such a large country with slow communication. Travel was faster by sea or river. The different estates of the realm—the clergy, the nobility, and commoners—sometimes met in the "Estates General." But this group had no real power; it could only ask the king for things, not make laws.

The Catholic Church controlled about 40% of the wealth. The king, not the pope, chose bishops. However, he usually had to negotiate with noble families linked to local churches.

The nobility was second in wealth, but they were not united. Each noble had their own lands, local connections, and military force.

Cities had a semi-independent status, controlled by leading merchants and guilds. Paris was the largest city, with 220,000 people in 1547. Lyon and Rouen each had about 40,000 people. Lyon had strong banking and culture.

Peasants made up most of the population. In 1484, about 97% of France's 13 million people lived in rural villages. In 1700, at least 80% of the 20 million people were peasants.

In the 17th century, peasants were connected to the market economy. They invested in farming and often moved between villages or towns. Moving for work was the main way to improve one's social standing.

Language and Culture

Most peasants spoke local dialects. But an official language grew in Paris, and French became the language of Europe's nobles and diplomacy. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V joked, "I speak Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to my horse."

Because of its international status, there was a desire to standardize French. Several reforms made it more uniform. The Renaissance writer François Rabelais helped shape French as a literary language, bringing back Greek and Latin words. Jacques Peletier du Mans also reformed French, improving the number system.

France Grows Stronger (15th and 16th Centuries)

After the death of Charles the Bold in 1477, France and the Habsburgs began a long process of dividing his rich Burgundian lands, leading to many wars. In 1532, Brittany became part of the Kingdom of France.

France fought in the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the start of early modern France. Francis I faced powerful enemies and was captured at Pavia. The French king then sought allies and found one in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Admiral Barbarossa captured Nice in 1543 and gave it to Francis I.

In the 16th century, the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs were the strongest power in Europe. The many lands of Charles V surrounded France. The Spanish Tercio (a type of military unit) was very successful against French knights. Finally, in 1558, the Duke of Guise took Calais from the English.

The "Beautiful 16th Century"

Historians call the period from about 1475 to 1630 the "beautiful 16th century." This was a time of peace, prosperity, and hope across the nation, with steady population growth. Paris, for example, grew to 200,000 people by 1550. In Toulouse, the Renaissance brought wealth that changed the city's architecture. In 1559, Henry II of France signed peace treaties with Elizabeth I of England and Philip II of Spain. This ended long conflicts between France, England, and Spain.

Religious Wars: Protestants and Catholics (1562–1629)

The Protestant Reformation, mainly inspired by John Calvin in France, began to challenge the Catholic Church. Calvin, from Geneva, Switzerland, was dedicated to reforming his homeland. He provided the ideas, worship style, and social rules for the new religion. He also created church and political structures.

Between 1555 and 1562, over 100 ministers were sent to France. However, French King Henry II severely punished Protestants under the Edict of Chateaubriand (1551). The two main Calvinist (Huguenot) strongholds were southwest France and Normandy, but Catholics were still the majority there. A renewed Catholic reaction, led by the powerful Francis, Duke of Guise, led to a massacre of Huguenots at Vassy in 1562. This started the first of the French Wars of Religion. English, German, and Spanish forces got involved, supporting either Protestants or Catholics.

King Henry II died in 1559. He was followed by his three sons, who were either too young or weak rulers. Henry's widow, Catherine de' Medici, became a key figure in the early Wars of Religion. She is often blamed for the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed in Paris and other parts of France.

The Wars of Religion ended with the War of the Three Henrys (1584–98). During this war, King Henry III's bodyguards killed Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic league. In revenge, a priest killed Henry III in 1589. This led to the Huguenot Henry IV becoming king. To bring peace, he converted to Catholicism, famously saying, "Paris is worth a Mass." He issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which gave Protestants religious freedom and ended the civil war. Huguenots could hold services in certain towns, control and fortify eight cities, and had equal civil rights with Catholics.

Henry IV was killed in 1610 by a fanatical Catholic.

In 1620, the Huguenots declared a constitution for the 'Republic of the Reformed Churches of France'. The chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), used the full power of the state to stop this. Religious conflicts continued under Louis XIII. Richelieu forced Protestants to give up their army and fortresses. This conflict ended with the Siege of La Rochelle (1627–28), where Protestants and their English supporters were defeated. The following Peace of Alais (1629) confirmed religious freedom but removed Protestant military defenses.

Many Huguenots fled France due to persecution, going to Protestant countries in Europe and America.

Thirty Years' War (1618–1648)

The religious conflicts in France also affected the Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire. The Thirty Years' War weakened the Catholic Habsburgs. Even though Cardinal Richelieu had fought Protestants in France, he joined the war on their side in 1636 because it was in France's national interest. Habsburg forces invaded France, attacked Champagne, and almost reached Paris.

Richelieu died in 1642 and was replaced by Cardinal Mazarin. Louis XIII died a year later and was replaced by Louis XIV. France had skilled commanders like Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé and Henri de la Tour d'Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne. French forces won a key victory at Rocroi (1643), destroying the Spanish army. The Truce of Ulm (1647) and the Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the war.

Some challenges remained. France faced civil unrest called The Fronde. This turned into the Franco-Spanish War in 1653. Louis II de Bourbon joined the Spanish army but was defeated at Dunkirk (1658). The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) forced harsh terms on Spain, and France gained Northern Catalonia.

During this time, René Descartes used logic and reason to answer philosophical questions, creating what is called Cartesian Dualism in 1641.

French Colonies (16th and 17th Centuries)

In the 16th century, the king began claiming North American lands and established several colonies. Jacques Cartier was a great explorer who traveled deep into American territories.

The early 17th century saw the first successful French settlements in the New World with the voyages of Samuel de Champlain. The largest settlement was New France, with towns like Quebec City (1608) and Montreal (founded in 1642).

Louis XIV: The Sun King (1643–1715)

Louis XIV, known as the "Sun King," ruled France from 1643 to 1715. His strong personal rule began in 1661 after his chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, died. Louis believed in the divine right of kings, meaning a king is above everyone but God. He continued to create a centralized state ruled from Paris, trying to remove old feudal ways and weaken the nobles. He built a system of absolute rule that lasted until the French Revolution. However, Louis XIV's long reign involved many wars that cost a lot of money.

His reign started during the Thirty Years' War and the Franco-Spanish war. His military architect, Vauban, became famous for his pentagonal fortresses. Jean-Baptiste Colbert managed the royal spending. French forces fought the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Saint Gotthard in 1664, winning with the help of 6,000 French troops.

France fought the War of Devolution against Spain in 1667. France's victory worried England and Sweden. With the Dutch Republic, they formed the Triple Alliance to stop Louis XIV's expansion. Louis II de Bourbon had captured Franche-Comté, but Louis XIV agreed to the peace of Aachen. He did not annex Franche-Comté but gained Lille.

Peace was short-lived. War broke out again between France and the Dutch Republic in the Franco-Dutch War (1672–78). France attacked the Dutch Republic, joined by England. The Dutch stopped the French invasion by flooding their lands. The Dutch Admiral Michiel de Ruyter defeated the Anglo-French navy, forcing England to leave the war in 1674. The Netherlands eventually agreed to peace in the Treaties of Nijmegen, where France gained Franche-Comté and more land in the Spanish Netherlands.

In 1682, the royal court moved to the grand Palace of Versailles, which Louis XIV had greatly expanded. Louis XIV made many nobles live at Versailles. He controlled them with pensions and privileges, replacing their power with his own.

War between France and Spain started again. The War of the Reunions (1683–84) saw Spain and the Holy Roman Empire defeated again. In October 1685, Louis signed the Edict of Fontainebleau, ordering the destruction of all Protestant churches and schools in France. This led to many Protestants leaving France. Over two million people died in famines in 1693 and 1710.

France was soon in another war, the War of the Grand Alliance. This war was fought in Europe and North America. It was long and difficult (also called the Nine Years' War), but the results were unclear. The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 confirmed French rule over Alsace but rejected its claims to Luxembourg. Louis also had to leave Catalonia and the Palatinate. This peace was seen as a temporary break, and war was expected to start again.

In 1701, the War of the Spanish Succession began. The Bourbon Philip of Anjou was named heir to the Spanish throne. The Habsburg Emperor Leopold opposed this, fearing it would give too much power to the French Bourbons and upset the balance of power in Europe. England and the Dutch Republic joined Leopold against Louis XIV and Philip of Anjou. The allied forces, led by John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy, defeated the French army several times. The Battle of Blenheim in 1704 was France's first major land defeat since Rocroi in 1643. However, the very bloody battles of Ramillies (1706) and Malplaquet (1709) were Pyrrhic victories for the allies, meaning they lost too many men to continue. Led by Villars, French forces regained much lost ground in battles like Denain (1712). Finally, a compromise was reached with the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Philip of Anjou was confirmed as Philip V, king of Spain, but he was forbidden from inheriting the French throne.

Louis XIV wanted to be remembered as a supporter of the arts, like Louis IX. He invited Jean-Baptiste Lully to create the French opera. Jules Hardouin Mansart became France's most important architect, bringing the best of French Baroque architecture.

The wars were very expensive and did not lead to clear victories. France gained some land to the east, but its enemies grew stronger. Vauban, France's top military strategist, warned the King in 1689 that a hostile "Alliance" was too strong at sea. He suggested that France should allow its merchant ships to attack enemy merchant ships, avoiding their navies.

Changes in France and the World (1718–1783)

Louis XIV died in 1715. His five-year-old great-grandson, Louis XV, became king and ruled until 1774. In 1718, France was at war again, as Philip II of Orléans's regency joined the War of the Quadruple Alliance against Spain. King Philip V of Spain had to withdraw, realizing Spain was no longer a great power. Under Cardinal Fleury's rule, peace was kept as long as possible.

However, in 1733, another war started in central Europe over the Polish succession. France joined against the Austrian Empire. This time, there was no invasion of the Netherlands, and Britain stayed neutral. Austria was left alone against a French-Spanish alliance and suffered a military disaster. Peace was made in the Treaty of Vienna (1738), where France gained the Duchy of Lorraine through inheritance.

Two years later, in 1740, war broke out over the Austrian succession, and France joined. The war was fought in North America and India, as well as Europe. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) ended it with unclear terms. Everyone saw this as a temporary truce. Prussia was becoming a new threat, gaining much land from Austria. This led to the Diplomatic Revolution of 1756, where alliances changed. France was now allied with Austria and Russia, while Britain was allied with Prussia.

In North America, France allied with Native American peoples during the Seven Years' War. Despite early successes, French forces were defeated at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. In Europe, French attempts to take Hanover failed. In 1762, Russia, France, and Austria were close to defeating Prussia. But the Anglo-Prussian Alliance was saved by the "Miracle of the House of Brandenburg." At sea, naval defeats against British fleets in 1759 forced France to keep its ships in port. Finally, peace was made in the Treaty of Paris (1763), and France lost its North American empire.

Britain's success in the Seven Years' War made it the leading colonial power, surpassing France. France sought revenge and, under Choiseul, began to rebuild. In 1766, France annexed Lorraine. The next year, it bought Corsica from Genoa.

Having lost its colonies, France saw a chance for revenge against Britain. It allied with the Americans in 1778, sending an army and navy that turned the American Revolution into a world war. Spain and the Dutch Republic also joined France. Admiral de Grasse defeated a British fleet at Chesapeake Bay. Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette joined American forces to defeat the British at Yorktown. The war ended with the Treaty of Paris (1783), making the United States independent. The British Royal Navy won a major victory over France in 1782 at the Battle of the Saintes. France ended the war with huge debts and only gained the island of Tobago.

The French Enlightenment

The "Philosophes" were French thinkers in the 18th century who led the French Enlightenment. They were influential across Europe. They studied science, literature, philosophy, and society. Their main goal was human progress. They believed that a rational society would come from free and reasoned thinking. They also supported Deism and religious tolerance. Many thought religion had caused conflict for too long, and that logical thought was the way forward.

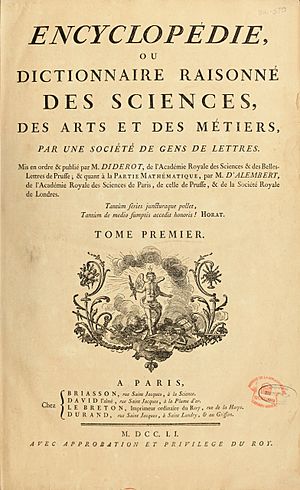

The philosopher Denis Diderot was the chief editor of the famous Enlightenment work, the 72,000-article Encyclopédie (1751–72). It greatly influenced learning worldwide.

Early in the 18th century, Voltaire and Montesquieu led the movement. It grew stronger as the century went on. Opposition was weakened by disagreements within the Catholic Church, the weakening of the absolute monarchy, and many expensive wars. So, the Philosophes' influence spread. Around 1750, they were most influential. Montesquieu published Spirit of Laws (1748), and Jean Jacques Rousseau published Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences (1750).

The leader of the French Enlightenment and a very influential writer was Voltaire (1694–1778). His many books included poems, plays, satires (like Candide), history, science, and philosophy. He also wrote many articles for the Encyclopédie. He was a witty opponent of the alliance between the French state and the church, and was exiled from France several times. In England, he learned about British thought and helped make Isaac Newton famous in Europe.

Astronomy, chemistry, mathematics, and technology thrived. French chemists like Antoine Lavoisier worked to replace old units of measurement with a scientific system. Lavoisier also discovered oxygen and hydrogen.

Revolutionary France (1789–1799)

Why the French Revolution Started

When King Louis XV died in 1774, he left his grandson, Louis XVI, with "ruined finances, unhappy subjects, and a faulty government." Still, people had faith in the king, and Louis XVI's arrival was welcomed.

A decade later, recent wars, especially the Seven Years' War (1756–63) and the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), had left the country bankrupt. The tax system was very inefficient. Several years of bad harvests and poor transportation caused food prices to rise, leading to hunger. The country became more unstable as the lower classes felt the royal court didn't care about their hardships.

In February 1787, the king's finance minister, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, called an Assembly of Notables. This group of nobles, clergy, and wealthy citizens was chosen to bypass local parliaments. They were asked to approve a new land tax that would include nobles and clergy for the first time. The assembly did not approve the tax. Instead, they demanded that Louis XVI call the Estates-General.

The National Assembly and the Bastille (January – July 1789)

In August 1788, the King agreed to call the Estates-General in May 1789. The Third Estate (commoners) demanded and got "double representation" to balance the First (clergy) and Second (nobles) Estates. However, voting was "by orders," meaning each estate had one vote, which canceled the double representation. This led the Third Estate to break away and, joined by some from other estates, declare the National Assembly. This was an assembly of "the People," not just estates.

To keep control, Louis XVI ordered the Salle des États, where the Assembly met, to be locked. The Assembly then met on a tennis court and took the Tennis Court Oath on 20 June 1789. They promised not to separate until a constitution was made. Some sympathetic nobles and clergy joined them. After the king fired his finance minister, Jacques Necker, fears grew that royalists might threaten the new Assembly.

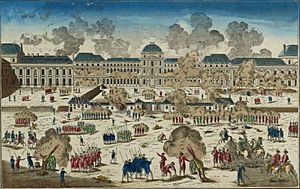

Paris soon saw riots and looting. The royal leadership left the city, and mobs gained support from the French Guard, including weapons. On 14 July 1789, the rebels targeted the Bastille fortress, a symbol of royal tyranny. Insurgents seized the Bastille prison. France now celebrates 14 July as 'Bastille day' or Quatorze Juillet, symbolizing the move from the Ancien Régime to a modern, democratic state.

Changes to the Church (October 1789 – December 1790)

In October 1789, a mob from Paris attacked the royal palace at Versailles. They were seeking help for their poverty. The royal family was forced to move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris.

Under the Ancien Régime, the Roman Catholic Church owned the most land in France. In November 1789, the Assembly decided to take over and sell all church property. This helped with the financial crisis.

In July 1790, the Assembly passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This law reorganized the French Catholic Church. Priests' salaries would now be paid by the state. The Church's right to tax crops was removed, and some clergy privileges were canceled. In October, 30 bishops said they could not accept the law. This increased public opposition. In late November 1790, the Assembly ordered all clergy to swear loyalty to the Civil Constitution. This made resistance stronger, especially in western France (Normandy, Brittany, and the Vendée). Few priests took the oath, and people turned against the revolution. Priests who swore the oath were called 'constitutional'; those who didn't were 'non-juring' or 'refractory'.

Creating a Constitutional Monarchy (June–September 1791)

In June 1791, the royal family secretly fled Paris in disguise to Varennes, near France's northeastern border. They hoped to find royalist support. But they were discovered and brought back to Paris. They were then kept under house arrest at the Tuileries.

In August 1791, Emperor Leopold II of Austria and King Frederick William II of Prussia issued the Declaration of Pillnitz. They said they wanted to help the French king "consolidate a monarchical government." They were preparing their troops. This angered the French, who militarized their borders.

Most of the Assembly still wanted a constitutional monarchy. They reached a compromise. Under the Constitution of 3 September 1791, France would be a constitutional monarchy. Louis XVI would be mostly a figurehead. The King had to share power with the elected Legislative Assembly. He still had his royal veto and could choose ministers. He had to swear an oath to the constitution. A decree said that breaking the oath or leading an army against the nation would mean he was no longer king.

War and Uprisings (October 1791 – August 1792)

On 1 October 1791, the Legislative Assembly was formed. Its members were elected by 4 million men (out of 25 million) who paid a certain amount of taxes. A group of Assembly members who wanted war against Austria and Prussia were called 'Girondins'. A group around Maximilien Robespierre, later called 'Montagnards' or 'Jacobins', argued against war. This disagreement grew stronger.

In response to the threat from Austria and Prussia in August 1791, Assembly leaders saw war as a way to strengthen their government. On 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria. In late April 1792, France invaded and conquered the Austrian Netherlands (today's Belgium and Luxembourg).

In summer 1792, Paris turned against the king. People hoped the Assembly would remove him, but the Assembly hesitated. On 10 August 1792, a large crowd of Parisians and soldiers marched on the Tuileries Palace. The king decided to leave and seek safety with his family in the Assembly. The Assembly 'temporarily relieved the king from his task'. On 19 August, a Prussian army invaded France and attacked Longwy. In late August 1792, elections were held for the new National Convention, with all men allowed to vote. On 26 August, the Assembly ordered the deportation of 'refractory priests' from western France, calling them "dangers to the fatherland." In response, peasants in the Vendée took over a town, moving closer to civil war.

Bloodshed and the Republic (September 1792)

On 2, 3, and 4 September 1792, about 300 volunteers and supporters of the revolution, angered by Verdun being captured by the Prussians, raided Parisian prisons. Rumors spread that foreign enemies were conspiring with prisoners. The Assembly and the Paris city council seemed unable to stop the bloodshed.

On 20 September 1792, the French won a battle against Prussian troops near Valmy. The new National Convention replaced the Legislative Assembly. From the start, the Convention was divided between the 'Montagnards' (or 'Jacobins') led by Robespierre, Danton, and Marat, and the 'Girondins'. Most representatives, called 'la Plaine', were neutral and kept debates moving. On 21 September, the Convention abolished the monarchy, making France the French First Republic. A new French Republican Calendar was introduced, renaming 1792 as year 1 of the Republic.

War and Civil War (November 1792 – Spring 1793)

Wars against Prussia and Austria had started in 1792. In November, France also declared war on Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. Former king Louis XVI was tried, convicted, and guillotined in January 1793.

In February 1793, a nationwide conscription (draft) for the army was introduced. This sparked a civil war in the Vendée in March. This region had been rebellious since 1790 due to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Meanwhile, France also declared war on Spain in March. That month, Vendée rebels won some victories. The French army was defeated in Belgium by Austria, and French general Dumouriez defected to the Austrians. The French Republic's survival was in danger.

On 6 April 1793, the Committee of Public Safety was created. This group of nine (later twelve) members acted as the executive government, accountable to the Convention. That month, the 'Girondins' accused Jean-Paul Marat of trying to destroy the people's power and encouraging violence. Marat was quickly found innocent, but this made the conflict between 'Girondins' and 'Montagnards' worse. In spring 1793, Austrian, British, Dutch, and Spanish troops invaded France.

Political Showdown (May–June 1793)

The rivalry between 'Montagnards' and 'Girondins' in the National Convention had been growing since late 1791. On 24 May 1793, Jacques Hébert, a Montagnard supporter, called on the sans-culottes (working-class Parisians) to revolt against the "henchmen of Capet and Dumouriez." Hébert was immediately arrested. The anger of the sans-culottes was aimed at the Girondins. On 25 May, a delegation from the Paris city council protested Hébert's arrest. The Convention's President, a Girondin, warned them: "If something happens to the nation's representatives, I declare that Paris will be totally destroyed."

On 29 May 1793, an uprising in Lyon overthrew the Montagnard rulers. Marseille, Toulon, and other cities saw similar events.

On 2 June 1793, the Convention's session in the Tuileries Palace became chaotic. Crowds, including 80,000 armed soldiers, surrounded the palace. Constant shouting from the public galleries, always favoring the Montagnards, made it seem like all of Paris was against the Girondins. Petitions were passed, accusing 22 Girondins. Barère, from the Committee of Public Safety, suggested that the Girondin leaders should resign to end the division. A decree was passed, expelling 22 leading Girondins from the Convention. That night, dozens of Girondins resigned and left.

In 1793, the Holy Roman Empire, the kings of Portugal and Naples, and the Grand-Duke of Tuscany declared war against France.

Counter-Revolution Suppressed (July 1793 – April 1794)

By summer 1793, most French departments opposed the central Paris government. Often, 'Girondins' who had fled Paris after June led these revolts. In Brittany, people who rejected the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790 started a guerrilla war called Chouannerie. But generally, the opposition against Paris became a struggle for power against the 'Montagnards' (Robespierre and Marat) who now controlled Paris.

In June–July 1793, Bordeaux, Marseilles, Brittany, Caen, and the rest of Normandy gathered armies to march on Paris. In July, Lyon guillotined the Montagnard head of its city council. Barère, from the Committee of Public Safety, urged tougher measures against the Vendée on 1 August: "We'll have peace only when no Vendée remains... we'll have to exterminate that rebellious people." In August, Convention troops besieged Lyon.

In August–September 1793, activists urged the Convention to do more to stop the counter-revolution. A delegation from the Paris city council suggested forming revolutionary armies to arrest hoarders and conspirators. Bertrand Barère, from the Committee of Public Safety, agreed on 5 September, saying: let's "make terror the order of the day!" On 17 September, the National Convention passed the Law of Suspects. This law ordered the arrest of all opponents of the government and suspected "enemies of freedom." This led to 17,000 death sentences by July 1794, a period historians call 'the (Reign of) Terror'.

On 19 September, the Vendée rebels again defeated a Republican army. On 1 October, Barère repeated his call to subdue the Vendée, calling it a "refuge of fanaticism." In October, Convention troops captured Lyon and restored a Montagnard government.

Rules for bringing someone before the Revolutionary Tribunal (created March 1793) were always broad. By August, political disagreement was enough to be summoned. There was no appeal against a Tribunal verdict. In late August 1793, an army general was guillotined for choosing timid strategies. In mid-October, former queen Marie Antoinette was tried and guillotined. In October, 21 former 'Girondins' Convention members were executed for supporting an uprising in Caen.

On 17 October 1793, the Republican army defeated the Vendéan army near Cholet. All surviving Vendée residents, tens of thousands, fled north into Brittany. A Convention representative was sent to Nantes to calm the region. By November 1793, revolts in Normandy, Bordeaux, and Lyon were crushed. Toulon was also defeated in December. Two representatives sent to punish Lyon executed 2,000 people. The Vendéan army in Brittany was defeated on 12 December 1793, with 10,000 rebels dying. Some historians say that after this defeat, Republican armies massacred 117,000 Vendéan civilians in 1794. Others disagree. Some historians believe the civil war lasted until 1796, with 450,000 deaths.

Executing Politicians (February–July 1794)

Maximilien Robespierre, a member of the Committee of Public Safety since July 1793, said in a speech on 5 February 1794 that Jacques Hébert and his group were "internal enemies." After a questionable trial, Hébert and some allies were guillotined in March. On 5 April, again at Robespierre's urging, Danton and 13 other politicians were executed. A week later, 19 more politicians were killed. This silenced the Convention members; they hardly dared to speak against Robespierre. A law passed on 10 June 1794 made trials even faster: if the Revolutionary Tribunal found enough proof of someone being an "enemy of the people," a defense lawyer was not allowed. The number of guillotine executions in Paris rose from about three a day to 29 a day.

Meanwhile, France's wars abroad were going well. Victories over Austrian and British troops in May and June 1794 opened Belgium for French conquest. However, cooperation within the Committee of Public Safety began to break down. On 29 June 1794, three of Robespierre's colleagues called him a dictator. Robespierre, shocked, left the meeting. This encouraged other Convention members to defy him. On 26 July, Robespierre's long speech was met with hostility instead of applause.

In the Convention session of 27 July 1794, Robespierre and his allies could barely speak due to constant interruptions. Finally, Robespierre's voice failed him. A decree was passed to arrest Robespierre, Saint-Just, and Couthon. On 28 July, they and 19 others were executed. On 29 July, 70 more Parisians were guillotined. The Law of 22 Prairial was then canceled. The 'Girondins' who had been expelled in June 1793 were brought back as Convention deputies if they were still alive.

Ignoring the Working Classes (August 1794 – October 1795)

After July 1794, most people ignored the Republican calendar and went back to the traditional seven-day weeks. A law on 21 February 1795 allowed freedom of religion and reconciliation with the refractory Catholic priests. But religious symbols outside churches or private homes, like crosses or bell ringing, were still forbidden. When church attendance grew, the government changed its mind. In October 1795, it again required all priests to swear oaths to the Republic.

In the very cold winter of 1794–95, with the French army needing more bread, food became scarce in Paris. Wood for heating was also rare. On 1 April 1795, a mostly female crowd marched on the Convention, demanding bread. But no Convention member sympathized; they told the women to go home. In May, a crowd of 20,000 men and 40,000 women invaded the Convention again. Still, they failed to make the Convention address the needs of the lower classes. Instead, the Convention banned women from all political meetings. Deputies who supported the uprising were sentenced to death.

In late 1794, France conquered present-day Belgium. In January 1795, they took over the Dutch Republic with the help of the Dutch 'patriots' movement, creating the Batavian Republic, a French satellite state. In April 1795, France made a peace agreement with Prussia. Later that year, peace was agreed with Spain.

Fighting Catholicism and Royalism (October 1795 – November 1799)

In October 1795, the Republic was reorganized. The one-chamber parliament (the National Convention) was replaced by a two-chamber system. The 'Council of 500' started laws, and the 'Council of Elders' reviewed them. Each year, one-third of the chambers were renewed. The executive power was held by five directors—giving the government its name, 'Directory'—with five-year terms. Each year, one director was replaced. The early directors did not understand the nation well. They saw Catholicism as counter-revolutionary and royalist. Local officials had a better sense of people's needs. One wrote to the interior minister: "Give back the crosses, the church bells, the Sundays, and everyone will cry: 'Long live the Republic!'"

French armies in 1796 advanced into Germany, Austria, and Italy. In 1797, France conquered the Rhineland, Belgium, and much of Italy.

Parliamentary elections in spring 1797 showed big gains for royalists. This scared the republican directors. They staged a coup d'état on 4 September 1797 (Coup of 18 Fructidor V) to remove two supposedly pro-royalist directors and some royalists from both Councils. The new government, still believing Catholicism and royalism were dangerous, started a new campaign to promote the Republican calendar (introduced in 1792) with its ten-day week. They tried to make the tenth day, décadi, a substitute for the Christian Sunday. Citizens opposed and mocked these decrees, and local officials refused to enforce them.

France was still fighting wars. In 1798, in Egypt, Switzerland, Rome, Ireland, Belgium, and against the U.S.A.. In 1799, in Baden-Württemberg. In 1799, when French armies abroad faced setbacks, the newly chosen director Sieyes thought the Directory needed a stronger executive. With general Napoleon Bonaparte, who had just returned, Sieyes prepared another coup d'état. It happened on 9–10 November 1799, replacing the five directors with three "consuls:" Napoleon, Sieyes, and Roger Ducos.

Napoleonic France (1799–1815)

During the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797), the Directory ruled France. Great Britain was still at war with France. A plan was made to take Egypt from the Ottoman Empire, a British ally. This was Napoleon's idea, and the Directory agreed to send the popular general away from France. Napoleon defeated the Ottoman forces at the Battle of the Pyramids (21 July 1798). He also sent scientists to explore Egypt. But a few weeks later, the British fleet under Admiral Horatio Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile (1–3 August 1798). Napoleon planned to move into Syria but was defeated at the Siege of Acre. He returned to France without his army.

The Directory was threatened by the Second Coalition (1798–1802). Royalists still wanted to restore the monarchy. Prussia and Austria did not accept their land losses from the previous war. In 1799, the Russian army drove the French from Italy. The Austrian army defeated the French in Switzerland. Napoleon then took power in a coup and created the Consulate in 1799. The Austrian army was defeated at the Battle of Marengo (1800) and again at the Battle of Hohenlinden (1800).

At sea, the French had some success at Boulogne. But Nelson's Royal Navy destroyed a Danish and Norwegian fleet at the Battle of Copenhagen (1801). The Second Coalition was defeated. Peace was made in the Treaty of Lunéville and the Treaty of Amiens. A short period of peace followed in 1802–03. During this time, Napoleon sold French Louisiana to the United States because it was hard to defend.

In 1801, Napoleon made a "Concordat" with Pope Pius VII. This started peaceful relations between church and state in France. Revolutionary policies were reversed, but the Church did not get its lands back. Bishops and clergy received state salaries, and the government paid for church buildings. Napoleon reorganized higher education.

In 1804, the senate named Napoleon Emperor, starting the First French Empire. Napoleon's rule was constitutional and, though autocratic, more modern than traditional European monarchies. The French Empire's creation led to the War of the Third Coalition. The French army was renamed La Grande Armée in 1805. Napoleon used propaganda and nationalism to control the French people. The French army won a big victory at Ulm (16–19 October 1805), capturing an entire Austrian army.

A French-Spanish fleet was defeated at Trafalgar (21 October 1805). This made plans to invade Britain impossible. Despite this naval defeat, the war was won on land. Napoleon inflicted one of their greatest defeats on the Austrian and Russian Empires at Austerlitz (2 December 1805), destroying the Third Coalition. Peace was made in the Treaty of Pressburg. The Austrian Empire lost the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Napoleon created the Confederation of the Rhine from former Austrian lands.

Alliances Against Napoleon

Prussia joined Britain and Russia, forming the Fourth Coalition. The French Empire also had many allies and subject states. The French army, though outnumbered, crushed the Prussian army at Jena-Auerstedt in 1806. Napoleon captured Berlin and went to Eastern Prussia. There, the Russian Empire was defeated at the Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807). Peace was made in the Treaties of Tilsit. Russia had to join the Continental System, and Prussia gave half its lands to France. The Duchy of Warsaw was formed from these lands, and many Polish troops joined the Grande Armée.

To harm the British economy, Napoleon set up the Continental System in 1807. He tried to stop European merchants from trading with Britain. A lot of smuggling frustrated Napoleon, and it hurt his economy more than his enemies'.

Free from the east, Napoleon turned west. The French Empire was still at war with Britain. Only Sweden and Portugal remained neutral. Napoleon then looked at Portugal. In the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1807), France and Spain allied against Portugal. French armies entered Spain to attack Portugal, but then took Spanish fortresses and the kingdom by surprise. Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother, became King of Spain after Charles IV gave up the throne.

This occupation of Spain and Portugal sparked local nationalism. Soon, the Spanish and Portuguese fought the French using guerilla tactics. They defeated French forces at the Battle of Bailén (June and July 1808). Britain sent ground support to Portugal, and French forces left Portugal after the Allied victory at Vimeiro (21 August 1808). France only controlled Catalonia and Navarre.

Another French attack was launched on Spain, led by Napoleon himself. However, the French Empire was no longer seen as unbeatable. In 1808, Austria formed the Fifth Coalition to break the French Empire. The Austrian Empire defeated the French at Aspern-Essling, but was beaten at Wagram. Polish allies defeated the Austrian Empire at Raszyn (April 1809). Though not as decisive as earlier defeats, the peace treaty in October 1809 took much land from Austria, weakening it further.

In 1812, war broke out with Russia, leading to Napoleon's disastrous French invasion of Russia (1812). Napoleon gathered the largest army Europe had ever seen to invade Russia. After a long march and the bloody Battle of Borodino, the Grande Armée entered Moscow. But they found it burning, part of Russia's scorched earth tactics. The Napoleonic army left Russia in late 1812, mostly destroyed by the Russian winter, exhaustion, and scorched earth. On the Spanish front, French troops were defeated at Vitoria (June 1813) and then at the Battle of the Pyrenees (July–August 1813). The Spanish guerrillas were uncontrollable, so French troops eventually left Spain.

Since France was defeated on two fronts, states conquered by Napoleon saw a chance to fight back. The Sixth Coalition formed under British leadership. German states joined against Napoleon. Napoleon was largely defeated at the Battle of the Nations in October 1813. His forces were outnumbered and overwhelmed during the Six Days Campaign (February 1814). Napoleon gave up his throne on 6 April 1814 and was exiled to Elba.

The conservative Congress of Vienna reversed the political changes from the wars. Napoleon suddenly returned, took control of France, raised an army, and marched on his enemies in the Hundred Days. It ended with his final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He was exiled to St. Helena, a remote island.

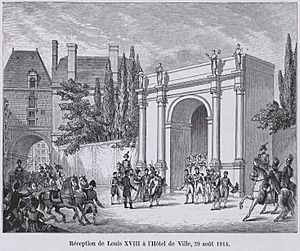

The monarchy was restored, and Louis XVIII, Louis XVI's younger brother, became king. Many exiles returned. However, many Revolutionary and Napoleonic reforms stayed in place.

Napoleon's Lasting Impact on France

Napoleon centralized power in Paris. All provinces were governed by powerful prefects he chose. These prefects were stronger than the royal officials of the ancien régime. They helped unite the nation, reduce regional differences, and shift all decisions to Paris.

Religion was a big issue during the Revolution. Napoleon solved most problems. He turned the clergy and many devout Catholics from being against the government to supporting him. The Catholic system was reestablished by the Concordat of 1801 (signed with Pope Pius VII). Church life returned to normal, though church lands were not given back. Priests and other religious people received state salaries. Napoleon reorganized higher education, focusing on technology.

The French tax system had collapsed in the 1780s. In the 1790s, the government took and sold church lands and lands of exiled nobles. Napoleon created a modern, efficient tax system. This ensured steady money for the government and made long-term financing possible.

Napoleon kept the conscription system from the 1790s. Every young man served in the army. Before the Revolution, nobles were officers. Now, promotion was based on merit.

The modern era of French education began in the 1790s. The Revolution abolished traditional universities. Napoleon replaced them with new institutions, like the École Polytechnique, focused on technology. Elementary schools received less attention.

The Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code, created under Napoleon's guidance, was very important. It was praised for its clarity and quickly spread across Europe and the world. It ended feudalism and freed serfs where it was adopted. The Code recognized civil liberty, equality before the law, and the state's non-religious nature. It ended the old right of primogeniture (only the eldest son inherited) and required inheritances to be divided equally among all children. The court system was standardized, with all judges appointed by the national government in Paris.

The Long 19th Century (1815–1914)

The century after Napoleon I was politically unstable. Every French leader from 1814 to 1873 spent time in exile. Governments changed often. Political deaths, imprisonments, and deportations were common.

France was no longer the dominant power it was before 1814. But it played a major role in European economics, culture, and diplomacy. The Bourbons were restored but had a weak rule. One branch was overthrown in 1830, and another in 1848. Napoleon's nephew was elected president and later made himself Emperor Napoleon III. He was overthrown after being defeated and captured by Prussians in 1870. This war humiliated France and made the new nation of Germany dominant. The Third Republic was established, but a return to monarchy was possible until the 1880s. France built an empire, especially in Africa and Indochina. The economy was strong, with a good railway system. The Rothschild banking family of France made Paris a major financial center alongside London.

Lasting Changes in French Society

The French Revolution and Napoleon brought big changes that the Bourbon restoration did not reverse. France became very centralized, with all decisions made in Paris. The country's political map was completely redrawn and made uniform. France was divided into over 80 departments, which still exist today. Each department had the same government structure and was controlled by a prefect appointed by Paris. The old, complex legal systems were abolished. There was now one standard legal code, managed by judges appointed by Paris, and supported by national police. Education was centralized, with the Grand Master of the University of France controlling everything from Paris. New technical universities opened in Paris, which still train the elite.

Conservatives were split between the old nobles who returned and the new elites who rose after 1796. The old nobles wanted their land back but felt no loyalty to the new government. The new elite mocked the old nobles as outdated. Both groups feared social disorder. But their distrust and cultural differences were too great for political cooperation.

The old nobles returned and got back much of their land. However, they lost all their old feudal rights over farmland. Peasants were no longer under their control. The old nobles had once liked Enlightenment ideas. Now, they were more conservative and supported the Catholic Church more. For top jobs, meritocracy (based on ability) was the new policy. Nobles had to compete with the growing business and professional class. Anti-church feelings became stronger, especially among some middle-class people and peasants.

In France, wealth was concentrated. The richest 10 percent of families owned 80-90 percent of the wealth from 1810 to 1914. This share then fell to about 60 percent. The top one percent's share grew from 45 percent in 1810 to 60 percent in 1914, then fell to 20 percent by 1970.

The "200 families" controlled much of the nation's wealth after 1815. This refers to the 200 shareholders of the Bank of France who could attend the annual meeting and cast all votes. Out of 27 million people, only 80,000 to 90,000 could vote in 1820.

Most French people were peasants or poor city workers. They gained new rights and a sense of possibility. Though freed from old burdens and taxes, peasants were still traditional. Many took out loans to buy land for their children. City workers were a small group, freed from medieval guild rules. However, France was slow to industrialize with large factories. Much work remained manual. This helped create small-scale, expensive luxury crafts for an international market. France was still localized, especially in language. But a new French nationalism emerged, showing pride in the Army and foreign affairs.

Religion in the 19th Century

The Catholic Church lost all its lands and buildings during the Revolution. These were sold or came under local government control. Bishops still ruled their dioceses (matching new department borders), but could only talk to the pope through the Paris government. Bishops, priests, and nuns were paid by the state. Old religious rites continued, and the government maintained religious buildings. The Church could run its own seminaries and some local schools, though this became a political issue later. Bishops were less powerful and had no political voice. However, the Catholic Church changed, focusing on personal faith, which helped it keep influence.

France remained mostly Catholic. The 1872 census counted 35.4 million Catholics out of 36 million people. The Revolution failed to destroy the Church, and Napoleon's 1801 agreement restored its status. The return of the Bourbons in 1814 brought back rich nobles who supported the Church, seeing it as a symbol of conservatism. But monasteries with vast lands and political power were gone. Much land was sold to city business owners who had no historical ties to the land or peasants.

Few new priests were trained from 1790–1814, and many left the church. The number of parish clergy fell from 60,000 in 1790 to 25,000 in 1815. Some regions, especially around Paris, had few priests. But some traditional regions held strongly to their faith, led by local nobles.

The Church's comeback was slow in larger cities and industrial areas. With missionary work, a new focus on worship, and support from Napoleon III, there was a revival. By 1870, there were 56,500 priests, a younger and more active force in villages and towns, with many schools and charities. Conservative Catholics controlled the government from 1820 to 1830, but often played smaller political roles or fought against republicans, liberals, and socialists.

Economic Changes

French economic history since the late 18th century was shaped by three things: the Napoleonic Era, competition with Britain in industrialization, and the "total wars" of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. France's per person growth was slightly less than Britain's. However, Britain's population tripled, while France's grew by only a third. So, Britain's overall economy grew much faster.

For 1870–1913, France's per person growth was about average among 12 advanced countries. But its population growth was very slow. So, in terms of total economic size, France was almost last, just ahead of Italy. The 12 countries averaged 2.7% total output growth per year, but France averaged only 1.6%.

The average size of factories was smaller in France. Machinery was often older, productivity lower, and costs higher. Old ways of making things by hand lasted longer. Big modern factories were rare. France did not catch up with Britain and was overtaken by Belgium, Germany, and the United States.

Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830)

This period was called the Bourbon Restoration. It was marked by conflicts between extreme royalists, who wanted to bring back the absolute monarchy, and liberals, who wanted a stronger constitutional monarchy. Louis XVIII was the younger brother of Louis XVI. He ruled from 1814 to 1824. When he became king, Louis issued a constitution called the Charter. It kept many freedoms gained during the French Revolution. It also created a parliament with an elected Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Peers chosen by the king.

Review of the Restoration

After two decades of war and revolution, the restoration brought peace and prosperity. Many historians describe this time as "one of the happiest periods in [France's] history."

France recovered from the disruption of wars and killings. It was peaceful. It paid a large war debt to the winners without trouble. The occupation soldiers left peacefully. The population grew by 3 million. Prosperity was strong from 1815 to 1825. National credit was strong, public wealth increased, and the national budget had a surplus every year. In the private sector, banking grew greatly, making Paris a world financial center. The Rothschild family became famous. Communication improved with better roads, longer canals, and steamboat traffic. Industrialization was slower than in Britain and Belgium. The railway system had not yet appeared. Industry was heavily protected by tariffs, so there was little demand for new ideas.

Culture flourished with new romantic ideas. Debates were of high quality. Châteaubriand and Madame de Staël were famous for romantic literature. De Staël contributed to political and literary sociology. History thrived, with François Guizot and Benjamin Constant learning from the past. The paintings of Eugène Delacroix set standards for romantic art. Music, theater, science, and philosophy also flourished. Higher education thrived at the Sorbonne. New institutions made France a leader in many fields.