History of the papacy facts for kids

The history of the papacy tells the story of the popes, who are the leaders of the Catholic Church. This story goes all the way back to Saint Peter, who Catholics believe was the first pope, and continues to today.

For the first 300 years, many of Peter's successors, the bishops of Rome, were not well-known. Most of them faced great danger and were even killed for their faith during times when Christians were persecuted. During the early days of Christianity, the bishops of Rome did not have any political power. This changed around the time of Emperor Constantine I.

After the Western Roman Empire fell around 476 AD, the popes in the Middle Ages were often influenced by the rulers of Italy. These times are known as the Ostrogothic, Byzantine, and Frankish Papacies. Over many years, the popes gained control over a part of Italy known as the Papal States. Later, powerful Roman families took over the influence that kings once had.

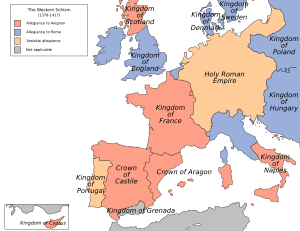

From 1048 to 1257, the popes often had disagreements with the leaders and churches of the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire). A big split, called the East–West Schism, happened, dividing the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. From 1257 to 1377, even though the pope was the bishop of Rome, he lived in other cities like Viterbo, Orvieto, Perugia, and finally Avignon. When the popes returned to Rome after the Avignon period, another big division happened called the Western Schism. During this time, there were two, and sometimes even three, people claiming to be the rightful pope.

The Renaissance Papacy is famous for supporting art and architecture. Popes were also very involved in European politics and faced challenges to their authority. After the Protestant Reformation began, the popes led the Catholic Church through the Counter-Reformation. During the Age of Revolution, the popes saw the Church lose a lot of its wealth, especially during the French Revolution. The Roman Question, which came from Italian unification, led to the loss of the Papal States and the creation of Vatican City.

Contents

- Popes in the Roman Empire (until 493 AD)

- The Middle Ages (493–1417 AD)

- Modern Era (1417–present)

- See also

Popes in the Roman Empire (until 493 AD)

Early Christian Leaders

Catholics believe the pope is the successor to Saint Peter and the first bishop of Rome. The Church teaches that popes hold a special place among all bishops, similar to how Peter was special among the Apostles.

Pope Clement I, one of the earliest Church leaders, wrote a letter to the Corinthians. This letter is seen as the first example of the pope using his authority over other churches. Clement told the Corinthians to stay united and end their disagreements. This letter was so respected that some even thought it should be part of the New Testament.

Some people disagree that Peter and his early successors had complete authority over all early churches. They believe the bishop of Rome was simply "first among equals." However, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches were one church for a long time, until a formal split over the pope's authority in 1054 AD.

Many of the bishops of Rome in the first three centuries are not well-known. But it is said that most of Peter's early successors faced great suffering and were killed for their faith during times of persecution.

From Constantine's Time (312–493 AD)

The story of Emperor Constantine I's victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312 AD) says he saw a vision of a Christian symbol in the sky. The next year, Constantine allowed Christians to practice their faith freely. In 325 AD, he called the First Council of Nicaea, which was the first big meeting of Christian leaders. The pope did not even attend this council. The first bishop of Rome to be called "Pope" was Pope Damasus I (366–84 AD). Also, between 324 and 330 AD, Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to a new city, which became Constantinople.

There was a famous story called the "Donation of Constantine," which was a fake document from the 8th century. It claimed that Constantine gave his crown to Pope Sylvester I and that Sylvester baptized him. In reality, Constantine was baptized by a different bishop just before he died. Even though the "Donation" was fake, Constantine did give the Lateran Palace to the bishop of Rome. He also started building the Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, where St. Peter was believed to be buried.

Pope Leo I (440–461 AD), also known as Leo the Great, was very important. He was later called a "Doctor of the Church." During his time, the word "Pope" began to mean only the Bishop of Rome.

The Middle Ages (493–1417 AD)

Ostrogothic Influence (493–537 AD)

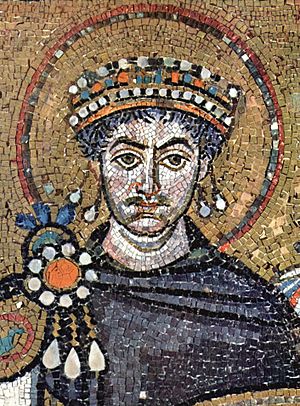

The Ostrogothic Papacy lasted from 493 to 537 AD. During this time, the popes were heavily influenced by the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy. The Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great and his successors had a big say in who became pope. This period ended when Emperor Justinian I re-conquered Italy, starting the Byzantine Papacy.

The Ostrogoths' influence was clear when two men were elected pope in 498 AD. Pope Symmachus won, but it was the first time money was used to influence a papal election. Symmachus also started the practice of popes naming their own successors.

Theodoric was generally fair to the Catholic Church and did not interfere with its beliefs. Ostrogothic influence ended when Justinian took Rome. He even removed Pope Silverius and put his own choice, Pope Vigilius, in power.

Byzantine Influence (537–752 AD)

The Byzantine Papacy was a time from 537 to 752 AD when the popes needed the approval of the Byzantine Emperors to be officially recognized. Many popes during this time were chosen from people who had worked closely with the emperor or were from Greek, Syrian, or Sicilian backgrounds. Justinian I brought back Roman rule to Italy and chose the next three popes. This practice continued for a long time.

Most popes during this period accepted the emperor's right to confirm their election. However, there were often disagreements between the pope and the emperor over religious beliefs, like whether Jesus had one will or two, or whether religious images should be used. Rome became a mix of Western and Eastern Christian traditions during this time.

Pope Gregory I (590–604 AD) was a key figure. He worked to strengthen the pope's authority in Rome and encouraged missionary work in northern Europe, including England.

The Duchy of Rome was a Byzantine area ruled by an imperial official. The pope became the main leader of the people in this area, especially against the Lombards. In 728 AD, the Lombard King Liutprand gave the Castle of Sutri back to Pope Gregory II as a gift. Popes continued to recognize the emperor's rule.

Frankish Influence (756–857 AD)

In 751 AD, the Lombards took Ravenna and threatened Rome. To get help, Pope Stephen II traveled to visit the Frankish king, Pepin III. The pope crowned Pepin as king. Pepin then invaded Italy twice, driving the Lombards away from Ravenna's territory. Instead of giving the land back to the Byzantine emperor, Pepin gave large parts of central Italy to the pope.

This land, given in the "Donation of Pepin" in 756 AD, made the papacy a political power. This was the start of the Papal States, which the popes ruled until 1870. For the next 11 centuries, the story of Rome was closely tied to the story of the papacy.

After being attacked in Rome, Pope Leo III visited Charlemagne in 799 AD. In 800 AD, Charlemagne came to Rome. During a ceremony on Christmas Day, the pope unexpectedly crowned Charlemagne as emperor. Charlemagne accepted the honor.

Charlemagne's successor, Louis the Pious, also got involved in papal elections. Popes then had to promise loyalty to the Frankish Emperor. The election of Pope Gregory IV was delayed for six months to get Louis's approval.

Influence of Powerful Roman Families (904–1048 AD)

The period from 904 to 964 AD is sometimes called the "dark age" of the papacy. During this time, the popes were controlled by a powerful and sometimes corrupt noble family called the Theophylacti.

Conflicts with Emperors and the East (1048–1257 AD)

The title of Holy Roman Emperor was often fought over. Italy became part of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 AD. When Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor visited Rome in 1048, he found three rival popes. He removed all three and put his own choice, Pope Clement II, in power.

From 1048 to 1257, the popes often clashed with the Holy Roman Emperors. A major dispute was the Investiture Controversy, about who could appoint bishops. Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor famously walked to Canossa in 1077 to meet Pope Gregory VII. Even though the emperor later gave up the right to appoint bishops in 1122, the issue came up again.

Long-standing differences between the East and West also led to the East–West Schism. Both Western and Eastern Church leaders had attended the first seven big Church councils. But growing differences in beliefs, language, and politics finally led to them separating. Pope Urban II (1088–99) called a council in 1095, hoping to reunite the Churches and help the Byzantines against the Seljuk Turks. His speech encouraged the First Crusade.

During this time, the way popes were chosen became more organized. In 1059, Pope Nicholas II said that only the College of Cardinals could vote in papal elections. These rules developed into the modern papal conclave.

The Wandering Popes (1257–1309 AD)

The pope is the bishop of Rome, but he doesn't always have to stay there. In the 13th century, political problems in Italy forced the pope and his court to move to different cities like Viterbo, Orvieto, and Perugia. The cardinals would meet in the city where the last pope died to elect a new one. These host cities gained prestige and economic benefits, but they also risked being taken over by the Papal States if the pope stayed too long.

Rome itself was unstable, with noble families building many fortified towers. Popes increasingly spent their time in palaces outside Rome.

Avignon Papacy (1309–1377 AD)

During this period, seven popes, all French, lived in Avignon, France, starting in 1309. These popes included Pope Clement V and Pope Gregory XI. The French King had a lot of control over the papacy at this time. In 1378, Gregory XI moved the pope's home back to Rome and died there.

Western Schism (1378–1417 AD)

After Pope Gregory XI died in Rome, French cardinals elected their own pope, Robert of Geneva, who took the name Clement VII. This started the "Western Schism," a difficult time from 1378 to 1417. During this period, the Catholic Church was divided, with different groups supporting different people who claimed to be the pope.

A big meeting called the Council of Constance finally solved the problem in 1417. In 1415, one of the rival popes, John XXIII, fled but was brought back and removed from office. The Roman pope, Gregory XII, willingly resigned. The council then elected Pope Martin V as the one true pope, ending the schism.

Modern Era (1417–present)

Renaissance Papacy (1417–1534 AD)

From the election of Pope Martin V in 1417 until the Reformation, Western Christianity was mostly united. Martin V brought the papacy back to Rome in 1420. Although there were disagreements, they were usually settled through the established process of electing a pope.

Unlike kings, popes were not born into their roles. So, they often promoted their family members to important positions, a practice called nepotism. This led to a wealthy group of cardinals, many of whom were relatives of popes or representatives of European kingdoms. These rich popes and cardinals supported Renaissance art and architecture, rebuilding many famous landmarks in Rome.

The Papal States began to act more like a modern country during this time. The popes became very involved in European wars and diplomacy. Pope Julius II was even known as "the Warrior Pope" because he used military force to expand the papacy's land and wealth. Popes used their armies not just for their families, but also to protect the Church's long-held territories. Before the Western Schism, the papacy earned money from its spiritual duties. But during this period, popes relied more on income from the Papal States. With expensive wars and building projects, popes also raised money by selling indulgences and Church offices.

Popes were often asked to settle arguments between powerful countries. For example, after Columbus discovered America in 1492, Pope Alexander VI issued special orders that gave Spain the right to colonize most of the New World.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation (1517–1580 AD)

This period saw major changes in the Church. The Protestant Reformation challenged the pope's authority, and the Catholic Church responded with its own reforms, known as the Counter-Reformation.

Baroque Papacy (1585–1689 AD)

The time of Pope Sixtus V (1585–1590) marked the final stage of the Catholic Reformation. His main goal was to rebuild Rome into a grand European capital, making it a visual symbol of the Catholic Church.

During the Age of Revolution (1775–1848 AD)

Popes during this time saw the Church lose a lot of its property and wealth. This happened during the French Revolution and other revolutions across Europe.

The Roman Question (1870–1929 AD)

The last eight years of Pope Pius IX's long time as pope were spent as a "prisoner of the Vatican." Catholics were not allowed to vote in national elections. However, they could vote in local elections and had some success there. Pius IX worked to create new dioceses and appoint bishops. He believed his successor should continue his love for the Church.

Pope Leo XIII was known as a great diplomat. He improved relations with many countries. However, he continued Pius IX's policies toward Italy because of strong anti-Catholic feelings there. He had to defend the Church's freedom against attacks on education, property, and even physical attacks. At one point, people tried to throw the body of the deceased Pope Pius IX into the Tiber river. The pope even thought about moving the papacy to cities in Austria.

Leo XIII's writings changed the Church's views on its relationship with governments. In his 1891 writing, Rerum novarum, he spoke for the first time about social inequality and justice, especially for workers. Later popes, like Pope Pius XI, Pope Pius XII, Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI, and Pope John Paul II, continued to expand on these teachings about workers' rights, private property, and social issues.

From the Creation of Vatican City (1929 AD) to Today

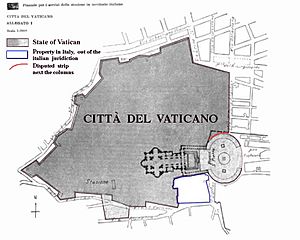

The time of Pope Pius XI was marked by a lot of diplomatic work. His Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, helped create the Lateran Treaty in 1929. This treaty was signed by Benito Mussolini for Italy and Cardinal Gasparri for the pope.

The Lateran Treaty created the state of Vatican City and gave the Holy See full independence. The pope promised to remain neutral in international conflicts unless asked to help. The treaty also made Catholicism the official religion of Italy and settled all financial claims the Holy See had against Italy for losing the Papal States in 1870.

Another goal for the Vatican was a treaty with Germany. In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. He sent his vice chancellor, Franz von Papen, to Rome to negotiate. The treaty, called the Reichskonkordat, was signed in July 1933.

Between 1933 and 1939, the Vatican sent 55 protests about Germany breaking the Reichskonkordat. In 1937, Pope Pius XI issued a strong letter called Mit brennender Sorge, written in German. It condemned the Nazi view that "exalts race, or the people, or the State... above their standard value."

World War II (1939–1945 AD)

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, the Vatican declared neutrality to avoid being drawn into the war. After World War II, Pope Pius XII focused on helping war-torn Europe, especially the millions of displaced people. He also worked to make the Catholic Church more international. His writings encouraged local Catholic missions to become independent dioceses. Pius XII insisted that local cultures were just as important as European culture. He made the College of Cardinals more international by appointing cardinals from Asia, South America, and Australia.

While the Church grew in the West, it faced severe persecution in Eastern Europe. Millions of Catholics came under Soviet rule, and many priests and religious people were killed or sent to labor camps. Communist governments in some countries almost completely destroyed the Catholic Church there.

From Vatican II (1962–1965 AD) to Today

On October 11, 1962, Pope John XXIII opened the Second Vatican Council. This important meeting brought many changes to Catholic practices. In 1965, Pope Paul VI and the Orthodox leader lifted the mutual excommunications that had been in place since the Great Schism of 1054.

The bishops at the council agreed that the pope has supreme authority over the Church. But they also defined "collegiality," meaning that all bishops share in this authority. Local bishops have authority as successors of the Apostles and as members of the larger Church. The pope acts as a symbol of unity and has extra authority to ensure that unity continues. During the council, Catholic bishops were careful to use language that would not upset Christians of other faiths.

Pope Paul VI (1963–1978) continued the efforts to unite Christians. He faced criticism from both traditional and liberal Catholics for trying to find a middle path during and after Vatican II. He was very passionate about peace during the Vietnam War. He also worked hard to fight world poverty. This pope was firm on basic Church teachings. He was the first pope to visit all five continents. Paul VI worked to make the Church less focused on Europe and more global, by including bishops from all over the world in its leadership.

When Pope John Paul II became pope in 1978, he was the first non-Italian pope in centuries. He is often credited with helping to end communism in Eastern Europe, especially in his home country of Poland. Lech Wałęsa, a leader of the Solidarity worker movement, said that John Paul II gave Poles the courage to stand up. Even Mikhail Gorbachev, the former Soviet leader, recognized the pope's role in the fall of communism.

John Paul II also continued to defend the human person and warned about the dangers of capitalism, especially in his writing Centesimus annus. He said that not everything the West offers reflects Christian values.

John Paul II's long time as pope brought a sense of stability back to the Catholic Church. He was firm on issues like women becoming priests and priestly celibacy. His strong style reminded some of Pope Pius XII. He warned against "viruses" of capitalism like secularism and consumerism.

After a long papacy, a new chapter began with the election of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005. In his first speech, he explained his view of a relationship with Christ:

Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way? If we let Christ enter fully into our lives, if we open ourselves totally to Him, are we not afraid that He might take something away from us? […] No! If we let Christ into our lives, we lose nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful and great. No! Only in this friendship do we experience beauty and liberation […] When we give ourselves to Him, we receive a hundredfold in return. Yes, open, open wide the doors to Christ – and you will find true life.

On February 11, 2013, Pope Benedict XVI announced he would resign. This was a very rare event. On March 13, 2013, Pope Francis was elected. He is the first Jesuit pope and the first pope from the Americas.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del papado para niños

In Spanish: Historia del papado para niños

- List of popes

- Papal States

- Papal Zouaves

- Index of Vatican City-related articles

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |