Papal conclave facts for kids

A papal conclave is a special meeting where cardinals of the Catholic Church gather to choose a new pope. The pope is the leader of the Catholic Church and Catholics believe he is the successor of Saint Peter. This way of electing a leader is the oldest still used today for a head of state, specifically for Vatican City.

The word "conclave" comes from the Latin words cum clave, meaning "with a key" or "locked". This is because the cardinals are locked away until they elect a new pope. This rule started after a very long election from 1268 to 1271. Pope Gregory X made a rule in 1274 that cardinals must be kept in seclusion until a pope is chosen. Today, conclaves are held in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City.

For a long time, the pope was chosen by the local clergy and people. But in 1059, the College of Cardinals became the only group allowed to elect the pope. Over time, other rules were added. In 1970, Pope Paul VI decided that only cardinals under 80 years old could vote. To be elected, a candidate needs a two-thirds majority vote. The most recent papal conclave happened in 2013, when Pope Francis was elected.

How Popes Were Chosen Over Time

The way popes are elected has changed a lot over nearly 2,000 years. Before 1059, popes were chosen by the local clergy and people, much like other bishops. The system we know today started to take shape in 1274. This was when Pope Gregory X issued a rule called Ubi periculum, after a very long election in Viterbo.

Another important rule was set in 1621 by Pope Gregory XV in his document Aeterni Patris Filius. This rule made it clear that a new pope needed a two-thirds majority vote from the cardinal electors. This two-thirds rule had actually been set earlier, in 1179, but it had changed a few times. Aeterni Patris Filius also stopped cardinals from voting for themselves in a way that would make them the deciding vote.

Who Can Vote?

In early Christian times, bishops were chosen by the clergy and regular church members. They often used a general agreement instead of formal votes. This sometimes led to disagreements and even rival popes.

In 769, a meeting in Rome removed the right of regular church members to reject the chosen pope. However, this right was given back to Roman noblemen in 862. A big change came in 1059 when Pope Nicholas II declared that cardinals would elect the pope. The cardinal bishops would meet first, then include the other cardinals for the actual vote. Later, in 1139, the need for approval from lower clergy and regular church members was removed. In 1179, all cardinals were given equal rights in the election.

For a long time, there were only a few cardinals, sometimes as few as seven. This small number meant that each vote was very important, and elections could last for months or even years. To speed things up, Gregory X's 1274 rule not only locked the cardinals in but also limited their servants to two and gradually reduced their food.

Cardinals didn't like these strict rules. They were temporarily stopped in 1276 and then fully removed later that year. Long elections started again until 1294, when Pope Celestine V brought back the 1274 rules.

Until 1899, some cardinals were not priests. But in 1917, a new rule said all cardinals must be priests. Since 1962, almost all cardinals have been bishops.

In 1587, Pope Sixtus V set the number of cardinals at 70. This was based on the idea of Moses having 70 elders to help him. However, this number has increased since Pope John XXIII started to include cardinals from more countries. In 1970, Paul VI ruled that cardinals who turn 80 before a conclave starts cannot vote. In 1975, he limited the number of voting cardinals to 120. While this is the official limit, popes have sometimes appointed more for short periods.

Who Can Be Chosen?

Originally, a person didn't have to be a priest to become pope. For example, St. Ambrose became Bishop of Milan even though he was still learning about Christianity. However, after a dispute in 767, a rule was made that only a cardinal priest or deacon could be elected. This rule was often ignored, and in 1059, it was formally changed to allow cardinals to choose a cleric from anywhere. In 1179, all restrictions on who could be elected were removed. In 1559, Pope Paul IV made it clear that only Catholics could be elected pope.

The last pope elected who was not already a cardinal was Pope Urban VI in 1378. The last person elected pope who was not already a priest was Pope Leo X in 1513. While the pope is the Bishop of Rome, he doesn't have to be Italian. Since 1978, the popes have been from Poland, Germany, and Argentina.

Popes were once elected by everyone agreeing (unanimously). But in 1179, the Third Council of the Lateran allowed a two-thirds majority. After 1621, cardinals were not allowed to vote for themselves. In 1945, Pope Pius XII removed this rule, requiring a two-thirds plus one majority. However, Pope John Paul II later changed it to a simple majority if there was a deadlock after many votes. In 2007, Pope Benedict XVI brought back the strict two-thirds majority rule.

In the past, cardinals used different ways to vote:

- Accessus: Cardinals could change their vote to help a candidate reach the two-thirds majority. This was stopped in 1945.

- Acclamation: All cardinals would agree on a pope as if inspired by the Holy Spirit. This was stopped in 1621.

- Compromise: If cardinals were stuck, they could let a small group of cardinals choose the pope for them.

- Scrutiny: This is voting by secret ballot.

The last election by compromise was in 1316, and the last by acclamation was in 1676. Today, scrutiny (secret ballot) is the only way to elect a new pope.

Outside Influence

For much of history, powerful rulers tried to influence who became pope. Roman emperors, then Ostrogothic kings, and later Byzantine emperors, had a say. For example, Byzantine emperors had to approve the election before a pope could take office. This caused long delays. Eventually, emperors only needed to be notified, not to approve.

In the 9th century, the Holy Roman Empire gained control over papal elections. Later, the Roman nobility also had a lot of influence. In 1059, the papal rule that limited voting to cardinals also recognized the Holy Roman Emperor's authority, but only as a favor from the pope. This meant the emperor couldn't just interfere.

From about 1600, some Catholic monarchs claimed a "right of exclusion" (jus exclusivae). This meant they could veto a candidate they didn't like. This was done through a special cardinal called a "crown-cardinal." This veto could only be used once per conclave. The last time this veto was used was in 1903, when Austria opposed a candidate. After this, Pope Pius X declared that any cardinal who used a government's veto in the future would be excommunicated (kicked out of the Church).

Seclusion and Rules

To solve long deadlocks in elections, local authorities sometimes forced cardinals to stay secluded. For example, in 1269, the people of Viterbo removed the roof of the building where the cardinals were meeting to make them hurry up!

To prevent long elections, Gregory X introduced strict rules in 1274. Cardinals had to be locked in a closed area without individual rooms. Food was given through a window, and after a few days, the amount of food was reduced. Cardinals also couldn't receive any church income during the conclave.

These rules were changed and brought back several times. In 1562, Pope Pius IV added more rules about the conclave's enclosure. Later, Gregory XV made very detailed rules about the election process and ceremonies. Many of these rules are still used today.

Since 1417, conclaves have usually taken place in Rome, mostly in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. Popes often updated the rules for electing their successors. The rules used today come from Pope John Paul II's 1996 document Universi Dominici gregis, with some small changes by Pope Benedict XVI.

Modern Practice

Today, the cardinals stay in a special building in Vatican City called the Domus Sanctae Marthae. They still vote in the Sistine Chapel.

The dean of the College of Cardinals has several important duties. If the dean is too old to vote, the vice-dean takes his place. If the vice-dean also cannot participate, the oldest cardinal bishop present takes over.

Some people have suggested that more people should be involved in electing the pope, perhaps by including more church leaders than just cardinals. However, the current rules state that only the College of Cardinals can elect the pope.

When a Pope Dies

When a pope dies, the cardinal camerlengo (chamberlain) confirms his death. Traditionally, he does this by calling out the pope's baptismal name. After confirming the death, the camerlengo says "sede vacante" ("The throne is empty"). He then takes the Ring of the Fisherman (the pope's ring) and the papal seal. These are later destroyed to show the end of the pope's reign and to prevent anyone from forging documents.

During the sede vacante (the time when there is no pope), the College of Cardinals takes on some limited powers. All cardinals are expected to attend meetings, except those who are ill or over 80 years old. Older cardinals can attend as non-voting members if they wish.

A smaller group of cardinals, including the camerlengo and three assistants, handle the Church's daily matters. New assistants are chosen every three days. These cardinals are responsible for keeping the election a secret.

The cardinals also arrange the pope's burial, which usually happens within four to six days after his death. There is also a nine-day period of mourning. The cardinals then set the date for the conclave, usually 15 days after the pope's death, but it can be extended to 20 days to allow all cardinals to arrive.

When a Pope Resigns

A pope can also leave office by resigning. Before Pope Benedict XVI resigned in 2013, no pope had resigned since Pope Gregory XII in 1415. Pope John Paul II's rules already covered the possibility of a pope resigning.

If a pope resigns, the Ring of the Fisherman is given to the cardinal camerlengo. In front of the cardinals, the camerlengo marks an "X" on the ring with a small hammer and chisel. This damages the ring so it cannot be used for official documents anymore.

Before the Sistine Chapel is Sealed

Before the election, cardinals listen to two sermons. These talks describe the current state of the Church and what qualities the new pope should have.

On the morning of the conclave, the cardinal electors attend a special Mass in Saint Peter's Basilica. In the afternoon, they gather in the Pauline Chapel and walk in a procession to the Sistine Chapel, singing a hymn to the Holy Spirit. They then take an oath to follow the rules, to protect the Church's freedom if elected, to keep everything secret, and to ignore any instructions from outside governments. The senior cardinal reads the oath, and the others repeat it while touching the Gospels.

"Outside, All of You!"

After all cardinals have taken the oath, the master of papal liturgical celebrations orders everyone else to leave the chapel. He traditionally calls out: ["Extra omnes!"] Error: {{Language with name/for}}: text has italic markup (help) (Latin for 'Outside, all [of you]'). Then he closes the door.

Only the cardinal electors and a few approved staff members can stay. These staff include a nurse (if a cardinal is ill), the secretary of the College of Cardinals, masters of ceremonies, and doctors. Priests are also available for confessions. A small number of servants prepare meals and clean. All staff must be approved by the camerlengo.

Secrecy is very important during the conclave. Cardinals and staff are forbidden from sharing any information about the election. They cannot communicate with anyone outside. Breaking this oath, or trying to listen in, results in excommunication (being removed from the Church). Electronic devices like phones and Wi-Fi are blocked in the Sistine Chapel.

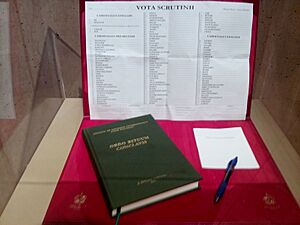

How Voting Works

On the first afternoon, one vote (called a "scrutiny") may be held. After that, a maximum of four votes are held each day: two in the morning and two in the afternoon. Before each voting session, the cardinals take an oath to follow the conclave rules.

If no one is elected after three days of voting, the process pauses for a day of prayer. If still no result after more votes, there are more pauses for prayer and reflection. Eventually, if there's a deadlock, only the two candidates with the most votes in the last ballot can be chosen in a runoff election. A two-thirds majority is still needed, and these two candidates cannot vote for themselves.

The voting process has three parts: "pre-scrutiny," "scrutiny," and "post-scrutiny."

Before Voting

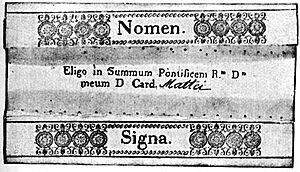

The masters of ceremonies prepare ballot papers that say Eligo in Summum Pontificem ('I elect as Supreme Pontiff'). Each cardinal gets at least two. Once cardinals start writing their votes, the secretary of the College of Cardinals and masters of ceremonies leave. The junior cardinal deacon then closes the door.

Nine cardinals are chosen by drawing lots: three are scrutineers (who count votes), three are infirmarii (who collect votes from sick cardinals), and three are revisers (who check the counts). These nine cardinals serve for the first two votes. New ones are chosen for the next two votes after lunch.

Casting Votes

Cardinals, in order of importance, bring their completed ballots to the altar where the scrutineers stand. Before placing their ballot, each cardinal takes an oath in Latin:

Testor Christum Dominum, qui me iudicaturus est, me eum eligere, quem secundum Deum iudico eligi debere.

I call as my witness Christ the Lord, who is to judge me, that I choose him whom according to God I judge ought to be elected.

If a cardinal is too sick to go to the altar, a scrutineer or infirmarii will collect their vote. All cardinals take this oath as they cast their ballots. If no one is chosen on the first vote, a second vote happens right away.

In the past, ballots were more complex and signed, but now they are simple cards. Since 1945, a cardinal can vote for himself. The two-thirds majority rule has been kept, except for a brief period under John Paul II.

After Voting

The scrutineers count all the votes. The revisers then check the ballots and lists to make sure there are no mistakes. After the count, the ballots are burned. If the first vote of a session doesn't result in an election, the cardinals immediately proceed to the next vote. The papers from both votes are burned together at the end of the second vote.

Smoke Signals

Since the early 1800s, the smoke from burning the ballots tells the world what's happening.

- Black smoke (fumata nera) means no pope has been elected yet.

- White smoke (fumata bianca) means a new pope has been chosen!

Before 1945, the type of wax on the ballots affected the smoke color. Since 1963, chemicals are added to make the smoke clearly black or white. Since 2005, church bells also ring when white smoke appears to confirm the election.

In 2013, the Vatican even shared the chemicals used: black smoke is made with potassium perchlorate, anthracene, and sulfur. White smoke is made with potassium chlorate, lactose, and pine rosin.

Acceptance and Announcement

Once a pope is elected, the cardinal dean asks him in Latin: Acceptasne electionem de te canonice factam in Summum Pontificem? ('Do you accept your canonical election as Supreme Pontiff?') The person is free to say no.

If he accepts, and he is already a bishop, he immediately becomes pope. If he is not a bishop, he must first be made a bishop before he can take office.

Since 533, the new pope also chooses a new name, called a papal name. Pope John II was the first to do this because his original name, Mercurius, was also the name of a Roman god. Most popes choose a new name. The last pope to keep his baptismal name was Pope Marcellus II (1555). The dean asks the new pope: Quo nomine vis vocari? ('By what name do you wish to be called?').

In the past, cardinals sat on special thrones with canopies. When a new pope accepted, all other cardinals would pull a cord to lower their canopies, showing that the period of shared leadership was over. This tradition ended in 1963 due to the increasing number of cardinals.

After accepting, the new pope goes to the "Room of Tears," a small room next to the Sistine Chapel. It's called this because of the strong emotions the new pope feels. He then puts on his new papal robes, which are provided in three sizes.

Next, the senior cardinal deacon appears on the balcony of Saint Peter's Basilica to announce the new pope. He uses a traditional Latin formula:

|

Annuntio vobis gaudium magnum; |

I announce to you a great joy; |

After the announcement, the new pope comes out onto the balcony to greet the crowd. A band plays the Pontifical Anthem. The pope then gives his first blessing, called the Urbi et Orbi blessing, which means "to the city and the world." Since Pope John Paul II, the last three popes have chosen to speak to the crowds first before giving the blessing. Pope Francis also led prayers for his predecessor and asked for prayers for himself.

In the past, popes were crowned with a special triple crown called the triregnum. However, all popes since Pope John Paul I have chosen a simpler inauguration ceremony instead of a coronation.

Important Papal Documents

Here are some of the key documents that have shaped the rules for electing a pope:

- In nomine Domini (1059)

- Ubi periculum (1274)

- Aeterni Patris Filius (1621)

- Ingravescentem aetatem (1970)

- Romano Pontifici eligendo (1975)

- Universi Dominici gregis (1996)

- De aliquis mutationibus in normis de electione Romani Pontificis (2007)

- Normas nonnullas (2013)

See Also

In Spanish: Cónclave para niños

In Spanish: Cónclave para niños

- Elective monarchy

- List of papal elections

- Politics of Vatican City

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |