Pope Paul IV facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pope Paul IV |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

Portrait by an unknown artist close to Jacopino del Conte, c. 1556 – c. 1560

|

|

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 23 May 1555 |

| Papacy ended | 18 August 1559 |

| Predecessor | Marcellus II |

| Successor | Pius IV |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 18 September 1505 by Oliviero Carafa |

| Created Cardinal | 22 December 1536 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Gian Pietro Carafa |

| Born | 28 June 1476 Capriglia Irpina, Kingdom of Naples |

| Died | 18 August 1559 (aged 83) Rome, Papal States |

| Previous post | Cardinal-Priest of San Pancrazio fouri le Mura (1536–55) |

| Motto | Dominus mihi adjutor ("The Lord is my helper") |

| Other Popes named Paul | |

| Papal styles of Pope Paul IV |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Pope Paul IV, whose birth name was Gian Pietro Carafa, was the leader of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States (a historical territory in Italy) from May 23, 1555, until his death in August 1559. He was born on June 28, 1476, and died on August 18, 1559.

Before becoming pope, he served as a special representative of the pope in Spain. During his time as pope, he faced an invasion of parts of the Papal States by Spain. He asked France for military help. After France was defeated and Spanish troops neared Rome, the Pope and Spain made a deal. Both French and Spanish forces left the Papal States, and the Pope decided to stay neutral between France and Spain.

Gian Pietro Carafa was made a bishop but later left that role in 1524. He then helped start a new religious group called the Theatines. He was later called back to Rome and became the Archbishop of Naples. He worked to improve the Inquisition, which was a system to deal with people who disagreed with Catholic teachings. He was against talking with the new Protestant movement in Europe.

In 1555, Carafa was chosen as pope. His time as pope was known for his strong desire to protect his homeland from the influence of Philip II of Spain and the Habsburg family. He appointed his nephew, Carlo Carafa, to an important position, but this caused problems. Scandals eventually forced Pope Paul IV to remove his nephew from office. He tried to fix some bad practices among church leaders in Rome, but his methods were seen as very strict. Even though he was old, he worked hard to make changes every day. He was determined to keep Protestants and Jewish people who had recently moved to the Papal States from gaining influence. He also issued a special rule called a Papal bull named Cum nimis absurdum. This rule allowed Jewish people to live in Rome but forced them to live in a specific area called the claustro degli Ebrei, which later became known as the Roman Ghetto. He became very unpopular by the time he died.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Gian Pietro Carafa was born in Capriglia Irpina, a town near Avellino in Italy. He came from the important Carafa family in Naples. His father, Giovanni Antonio Carafa, passed away in 1516. His mother, Vittoria Camponeschi, was from a noble family in Naples and had some Portuguese family connections.

Church Career

Becoming a Bishop

Gian Pietro Carafa was guided by his relative, Cardinal Oliviero Carafa. Oliviero gave up his position as bishop of Chieti so Gian Pietro could take it. With the approval of Pope Leo X, Gian Pietro became an ambassador to England. Then, he served as the pope's representative in Spain. While in Spain, he developed a strong dislike for Spanish rule, which later influenced his decisions as pope.

In 1524, Pope Clement VII allowed Carafa to leave his church positions. He joined a new religious group called the Theatines, known for their simple and strict way of life. After Rome was attacked in 1527, the Theatines moved to Venice. However, Pope Paul III (who wanted to make reforms) called Carafa back to Rome. He was asked to join a committee that was working to improve the papal court. This showed that the church was moving towards a more traditional way of thinking, as Carafa was a strong follower of Thomas Aquinas.

Becoming a Cardinal

In December 1536, Gian Pietro Carafa was made a Cardinal-Priest. He later became the Archbishop of Naples.

In 1541, a meeting called the Regensburg Colloquy tried to bring Catholics and Protestants in Europe back together, but it failed. Instead, some important Italians switched to the Protestant side. Because of this, Carafa convinced Pope Paul III to create a Roman Inquisition. This system was based on the Spanish Inquisition and was designed to find and punish people who were seen as heretics (those who went against church teachings). Carafa himself became one of the main leaders of the Inquisition. He was very strict and once said that he would even help punish his own father if he were a heretic.

Election as Pope

It was a surprise when Carafa was chosen to be the next pope after Pope Marcellus II died in 1555. He was known for being very strict and unyielding, and he was also quite old. Normally, he might have refused the honor. However, he accepted, perhaps because Emperor Charles V was against him becoming pope.

Carafa was elected on May 23, 1555. He chose the name "Paul IV" to honor Pope Paul III, who had made him a cardinal. He was officially crowned as pope on May 26, 1555. He took control of the Basilica of Saint John Lateran on October 28, 1555.

Papacy

As pope, Paul IV was very focused on protecting his homeland and its freedoms from foreign control. Like Pope Paul III, he was an enemy of the powerful Colonna family.

Paul IV was not happy when France signed a peace agreement with Spain in February 1556. He urged the French King Henry II to join the Papal States in attacking Spanish Naples. On September 1, 1556, King Philip II of Spain responded by invading the Papal States with 12,000 soldiers. French forces coming from the north were defeated and had to leave. The pope's armies were left alone and were also defeated. Spanish troops reached the edge of Rome. Fearing another attack on Rome, Paul IV agreed to declare the Papal States neutral. He signed a peace treaty on September 12, 1557.

His nephew, Carlo Carafa, became his main political advisor. Carlo worked to create an alliance with France. Carlo's older brother, Giovanni, was made the commander of the pope's army. Another nephew, Antonio, was put in charge of the papal guard. Their actions became well-known in Rome, and not in a good way. After the difficult war with Spain and many scandals, Paul IV publicly shamed his nephews and sent them away from Rome in 1559.

During the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church expected all Catholic rulers to see Protestant rulers as heretics. This meant their kingdoms were not considered legitimate. Paul IV issued a papal bull in 1555, recognizing Philip and Mary as King and Queen of England and Ireland. He also upset people in England by demanding that property taken during the dissolution of monasteries be returned. He also did not accept Elizabeth I of England as the rightful queen.

Paul IV strongly disliked Cardinal Giovanni Morone, believing he was secretly a Protestant. He even had him imprisoned. To prevent Morone from becoming pope and possibly changing the Church, Pope Paul IV made a rule. This rule stated that heretics and non-Catholics could not become pope.

Paul IV was very strict in his beliefs and lived a simple life. He was also very bossy. He believed that there was no salvation outside the Catholic Church. He used the Holy Office (the Inquisition) to stop groups he considered heretical. The Inquisition became even stronger under Paul IV. Few people, no matter how important, felt safe from his efforts to reform the Church. Even cardinals he disliked could be put in prison. He appointed Michele Ghislieri, who later became Pope Pius V, as the head of the Inquisition.

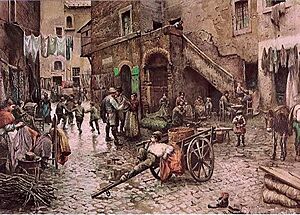

On July 17, 1555, Paul IV issued a very famous and controversial papal bull called Cum nimis absurdum. This rule ordered the creation of a Jewish ghetto in Rome. The pope set its boundaries near an area where many Jewish people already lived. He ordered walls to be built around it, separating it from the rest of the city. There was only one gate, which was locked every day at sunset. Jewish people had to pay for all the costs of building these walls.

The bull also limited Jewish people in other ways. They were only allowed to have one synagogue per city. In Rome, this meant seven places of worship were destroyed. All Jewish people were forced to wear special yellow hats, especially outside the ghetto. They were also forbidden from trading in anything except food and used clothes. Christians were encouraged to treat Jewish people as second-class citizens. If a Jewish person challenged a Christian, they could face harsh punishment. By the end of Paul IV's time as pope, the number of Jewish people in Rome had dropped by half. The ghetto he created lasted for over 300 years, until the Papal States ended in 1870. Its walls were torn down in 1888.

Paul IV was known for his strictness and his desire to bring back older traditions. Monks who had left their monasteries were forced to leave Rome and the Papal States. He stopped the practice where one person could collect money from a church job without doing the work.

All begging was forbidden. Even collecting money for Masses, which clergy used to do, was stopped. Paul IV reformed the way the papal government was run. He wanted to stop people from buying important positions. All government jobs, from the highest to the lowest, were given based on skill. He also saved a lot of money and reduced taxes. Paul IV created a special box, which only he had the key to, where people could leave complaints.

During his time as pope, censorship became very strict. One of his first actions was to stop paying Michelangelo a pension. He also ordered that the nude figures in The Last Judgment painting in the Sistine Chapel be covered more modestly. Paul IV also introduced the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, or "Index of Prohibited Books," to Venice. This was done to stop the spread of Protestant ideas. Under his rule, all books written by Protestants were banned, along with Italian and German translations of the Latin Bible.

In the Papal States, there were many Jewish people who had converted to Christianity but secretly kept their Jewish faith (called Marranos). In Rome and the port city of Ancona, they had done well under previous popes. They even had a promise that if they were accused of going back to their old faith, only the pope could judge them. But Paul IV, who was a strong leader of the Counter-Reformation, took away these protections. He started a campaign against them. As a result, 25 of them were burned at the stake in the spring of 1556.

Creating Cardinals

During his time as pope, Paul IV appointed 46 new cardinals in four different ceremonies. One of these was Michele Ghislieri, who later became Pope Pius V.

Death

Paul IV's health started to get worse in May 1559. He felt better in July, holding public meetings and attending Inquisition meetings. But he often fasted, and the summer heat made him weak again. He became bedridden, and by August 17, it was clear he would not live. Cardinals and other officials gathered by his bedside on August 18. Paul IV asked them to choose a "righteous and holy" successor and to keep the Inquisition, calling it "the very basis" of the Catholic Church's power. He died at 5 pm.

The people of Rome had not forgotten the suffering caused by the war he had started. Crowds gathered in the Piazza del Campidoglio and began rioting even before Paul IV died. His statue, which had been put up just months before, had a yellow hat placed on it. This was like the yellow hat Paul IV had forced Jewish people to wear in public. After a fake trial, the statue was thrown into the Tiber River.

The crowd broke into three city jails and freed over 400 prisoners. Then, they broke into the Inquisition offices near the Church of San Rocco. They killed the Inquisitor, Tommaso Scotti, and freed 72 prisoners. One of those freed was John Craig, who later worked with John Knox. The people ransacked the palace and then set it on fire, destroying the Inquisition's records. On the third day of rioting, the crowd removed the Carafa family symbol from all churches, monuments, and other buildings in the city.

Four or five hours after his death, Paul IV's body was taken to the Cappella Paolina in the Apostolic Palace. It lay there for people to see, and a choir sang a special service on the morning of August 19. Cardinals and many others then paid their respects to Paul IV. The priests of St. Peter's Basilica refused to take his body into the basilica unless they were paid the usual fees. Instead, they sang the service in a different chapel. Paul IV's body was then taken to the Sistine Chapel in the Apostolic Palace at 6 pm.

Paul IV's nephew, Cardinal-nephew Carlo Carafa, arrived in Rome late on August 19. Worried that the rioters might break in, Cardinal Carafa had Pope Paul IV buried quickly and without a ceremony. He was buried next to a chapel in St. Peter's. His remains stayed there until October 1566, when the next pope, Pius V, had them moved to Santa Maria sopra Minerva. In a chapel founded by Paul IV's uncle and mentor, Cardinal Oliviero Carafa, a tomb was built, and Paul IV's remains were placed there.

In Fiction

Paul IV appears as a character in the play The White Devil (1612).

In the novel Q, Gian Pietro Carafa is mentioned many times as a cardinal whose spy causes many problems for Protestants during the Reformation.

In Alison MacLeod's novel "The Hireling," Cardinal Caraffa was friends with Cardinal Reginald Pole. However, after Caraffa became pope, he turned against Pole and accused him of heresy. This happened even as Pole was trying to bring England back to the Catholic Church.

Pope Paul IV is a main villain in Sholem Asch's 1921 novel The Witch of Castile. The book shows a young Jewish woman in Rome being wrongly accused of witchcraft and burned at the stake. This story is set against the real persecution of Jewish people by Paul IV.

See also

In Spanish: Paulo IV para niños

In Spanish: Paulo IV para niños

- Cardinals created by Paul IV