John Knox facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Knox

|

|

|---|---|

19th-century engraving of Knox

|

|

| Born | c. 1514 Giffordgate, Haddington, Scotland

|

| Died | 24 November 1572 (aged 58 or 59) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Alma mater | University of St. Andrews |

| Occupation | Pastor, author, reformer |

| Spouse(s) | Margery Bowes Margaret Stewart |

| Children | with Bowes: Nathaniel Knox Eleazar Knox with Stewart: Martha Knox Margaret Knox Elizabeth Knox |

| Theological work | |

| Tradition or movement | Presbyterianism |

John Knox (Scottish Gaelic: Iain Cnocc) (born c. 1514 – 24 November 1572) was an important Scottish minister, theologian, and writer. He led the Reformation in Scotland. He also founded the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Knox was born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lothian. He likely studied at the University of St Andrews. He worked as a notary-priest. He was inspired by early church reformers like George Wishart. Knox joined the movement to change the Scottish church.

He became involved in big church and political events. These included the killing of Cardinal David Beaton in 1546. It also involved the actions of the regent Mary of Guise. French forces captured Knox in 1547. He was then sent away to England in 1549.

While in England, Knox worked for the Church of England. He became a royal chaplain to King Edward VI. He helped change the Book of Common Prayer. In England, he married his first wife, Margery Bowes. When Mary I became Queen of England, she brought back Catholicism. Knox had to leave his job and the country.

Knox moved to Geneva and then to Frankfurt. In Geneva, he met John Calvin. Calvin taught him a lot about Reformed theology and how to organize a church (Presbyterian polity). Knox created a new church service. This service was later used by the reformed church in Scotland. He then led the English refugee church in Frankfurt. But he had to leave due to disagreements about church services. This ended his connection with the Church of England. The University of Edinburgh has a copy of Knox's church service book. It was translated into Scots Gaelic and was the first book printed in any Gaelic language.

When Knox returned to Scotland, he led the Protestant Reformation. He worked with Scottish Protestant nobles. This movement was like a revolution. It led to Mary of Guise being removed from power. She governed Scotland for her young daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots. Knox helped write a new statement of faith. He also helped create the rules for the new reformed church, called the Kirk. He wrote his five-volume book, The History of the Reformation in Scotland, between 1559 and 1566. He remained the main religious leader for Protestants during Mary's reign. Knox spoke with the Queen several times. He warned her about supporting Catholic practices. After she was imprisoned for her husband Lord Darnley's death, and King James VI became king, Knox openly called for her execution. He continued preaching until his last days.

Contents

- John Knox's Early Life (1505–1546)

- Becoming a Protestant (1546–1547)

- Prisoner in French Galleys (1547–1549)

- Life in England (1549–1554)

- From Geneva to Frankfurt and Scotland (1554–1556)

- Return to Geneva (1556–1559)

- Revolution and End of the Regency (1559–1560)

- Reformation in Scotland (1560–1561)

- Knox and Queen Mary (1561–1564)

- Final Years in Edinburgh (1564–1572)

- John Knox's Legacy

- Selected Works by John Knox

- See also

John Knox's Early Life (1505–1546)

John Knox was born between 1505 and 1515. He was born in or near Haddington, East Lothian, Scotland. His father, William Knox, was a merchant. His mother's maiden name was Sinclair. She died when John was a child. His older brother, William, continued their father's business. This helped Knox with his international messages later on.

Knox probably went to the grammar school in Haddington. Back then, becoming a priest was often the only choice for those who liked to study. He then went to the University of St Andrews or maybe the University of Glasgow. He studied with John Major, a very famous scholar. Knox became a Catholic priest in Edinburgh in 1536.

Knox first appeared in public records as a priest and a notary in 1540. He was still doing this in 1543. He described himself as a "minister of the sacred altar" and a "notary by apostolic authority." Instead of working in a parish, he became a tutor for the sons of two lairds. These were Hugh Douglas of Longniddry and John Cockburn of Ormiston. Both of these landowners had started to follow the new ideas of the Reformation.

Becoming a Protestant (1546–1547)

Knox did not write down when or how he became a Protestant. But Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart likely influenced him greatly. Wishart was a reformer who left Scotland in 1538 to avoid punishment for heresy. He went to England, Germany, and Switzerland. While in Europe, he translated an important Protestant statement into English.

Wishart returned to Scotland in 1544. At this time, the regent, James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault, and Mary of Guise, along with Cardinal David Beaton, began to persecute Protestants. Wishart traveled Scotland, preaching about the Reformation. When he came to East Lothian, Knox became one of his closest friends. Knox even acted as his bodyguard, carrying a large sword to protect him.

In December 1545, Cardinal Beaton ordered Wishart's capture. Wishart was taken to St Andrews Castle. Knox was there when Wishart was arrested. He wanted to go with him, but Wishart told him, "No, go back to your children, and God bless you. One is enough for a sacrifice." Wishart was then put on trial by Beaton's accuser. On March 1, 1546, he was burned at the stake in front of Beaton.

Knox avoided arrest by following Wishart's advice to return to tutoring. He stayed with Douglas in Longniddry. Months later, he was still teaching Douglas's and Cockburn's sons. He thought about going to Germany with his students. While Knox was still a fugitive, Cardinal Beaton was killed on May 29, 1546. This happened inside St Andrews Castle. It was revenge for Wishart's execution. The attackers took over the castle. Their families and friends, about 150 men, joined them there. Among them was Henry Balnaves, a former government secretary. He arranged for England to financially support the rebels. Douglas and Cockburn suggested Knox take their sons to the castle for safety. They wanted him to continue teaching them reformed ideas. Knox arrived at the castle on April 10, 1547.

Knox's powerful preaching caught the attention of John Rough, the castle's chaplain. Rough preached about how a pastor should be chosen by the people. He then suggested Knox for the job. Knox was very emotional about this idea. He cried and ran to his room. But within a week, he gave his first sermon. His old teacher, John Major, was in the audience. Knox spoke about the Book of Daniel. He compared the Pope to the Antichrist. His sermon showed that he believed the Bible was the only authority. He also believed in "justification by faith alone." These ideas stayed with him his whole life. A few days later, a debate was held. Knox used it to state more of his beliefs. These included rejecting the Mass, Purgatory, and prayers for the dead.

Prisoner in French Galleys (1547–1549)

John Knox's time as a castle chaplain did not last long. The regent, Hamilton, wanted to make a deal with England to stop their support for the rebels. He also wanted to get the castle back. But Mary of Guise decided it could only be taken by force. She asked the king of France, Henry II, for help. On June 29, 1547, 21 French galleys arrived at St Andrews. They were led by Leone Strozzi. The French attacked the castle. They forced the defenders to surrender on July 31.

Protestant nobles and others, including Knox, were taken prisoner. They were forced to row in the French galleys. These galley slaves were chained to benches. They rowed all day without changing position. An officer watched them with a whip. They sailed to France and up the Seine River to Rouen. The nobles, like William Kirkcaldy and Henry Balnaves, were sent to different prisons in France. Knox and the other galley slaves went to Nantes. They stayed on the Loire through the winter. They were threatened with torture if they did not show respect during Mass on the ship.

In summer 1548, the galleys returned to Scotland. They were looking for English ships. Knox's health was very bad because of his harsh imprisonment. He had a fever, and others on the ship feared he would die. Even in this state, Knox remembered, his mind was clear. He comforted his fellow prisoners with hopes of being freed. While the ships were near the coast between St Andrews and Dundee, the church spires where he had preached came into view. James Balfour, another prisoner, asked Knox if he recognized the place. Knox replied that he knew it well. He recognized the steeple of the church where he first preached. He declared that he would not die until he had preached there again.

In February 1549, Knox was released. He had spent 19 months in the galley-prison. It is not clear how he gained his freedom. Later that year, Henry II of France and Edward VI of England arranged for the release of all remaining prisoners.

Life in England (1549–1554)

After his release, Knox went to England. The Reformation in England was less extreme than in other parts of Europe. But it had clearly broken away from Rome. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, and King Edward VI's regent, the Duke of Somerset, were strong Protestants. However, much work was still needed to bring reformed ideas to the church leaders and the people.

On April 7, 1549, Knox was allowed to work in the Church of England. His first job was in Berwick-upon-Tweed. He had to use the new 1549 Book of Common Prayer. This book kept the structure of old church services but changed the content to fit the reformed Church of England. Knox, however, changed how he used it. He made it fit the ideas of the European reformers. From the pulpit, he preached Protestant beliefs very effectively. His church grew larger.

In England, Knox met his wife, Margery Bowes (died c. 1560). Her father, Richard Bowes, was from an old Durham family. Her mother, Elizabeth Aske, was from a rich Yorkshire family. Elizabeth likely met Knox when he worked in Berwick. Letters show they had a close friendship. It is not known when Knox married Margery Bowes. Knox tried to get the Bowes family's approval. But her father and brother, Robert Bowes, were against the marriage.

By late 1550, Knox was a preacher at St Nicholas' Church in Newcastle upon Tyne. The next year, he became one of the King's six royal chaplains. On October 16, 1551, John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, took over from the Duke of Somerset as the young King's new regent. Knox spoke out against this change in a sermon. When Dudley visited Newcastle in June 1552, he heard Knox preach. He had mixed feelings about the fiery preacher. But he saw Knox as someone who could be useful.

Knox was asked to come to London to preach before the King's Court. In his first sermon, he asked for a change to the 1552 Book of Common Prayer. The service required people to kneel during communion. Knox and the other chaplains thought this was idolatry (worshipping idols). This led to a debate. Archbishop Cranmer had to defend the practice. The result was a compromise. The famous Black Rubric was added to the second edition. It stated that kneeling did not mean worshipping the bread and wine.

Soon after, Dudley offered Knox the bishopric of Rochester. Knox refused and went back to Newcastle. On February 2, 1553, Cranmer was told to make Knox the vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street, in London. This put him under the authority of the Bishop of London, Nicholas Ridley. Knox returned to London to preach before the King during Lent. He again refused the assigned job. Knox was then told to preach in Buckinghamshire. He stayed there until King Edward died on July 6. Edward's successor, Mary Tudor, brought back Roman Catholicism in England. She restored the Mass in all churches. England was no longer safe for Protestant preachers. Knox left for Europe in January 1554, following his friends' advice.

From Geneva to Frankfurt and Scotland (1554–1556)

Knox arrived in Dieppe, France. He then went to Geneva, where John Calvin was a powerful leader. When Knox arrived, Calvin was in a difficult situation. He had recently overseen the trial of a scholar named Michael Servetus for heresy. Knox asked Calvin four tough political questions. These included whether a minor could rule by divine right. He also asked if a woman could rule and give her power to her husband. And if people should obey ungodly rulers. Calvin gave careful answers. He sent Knox to another reformer, Heinrich Bullinger, in Zürich. Bullinger's answers were also careful. But Knox had already made up his mind. On July 20, 1554, he published a pamphlet. It attacked Mary Tudor and the bishops who helped her become queen. He also attacked the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

On September 24, 1554, Knox was invited to be a minister for English exiles in Frankfurt. He accepted the offer with Calvin's blessing. But as soon as he arrived, he faced conflict. The first refugees in Frankfurt used a changed version of the Book of Common Prayer. But newer refugees, like Edmund Grindal, wanted to follow the book more strictly. Knox and a friend, William Whittingham, wrote to Calvin for advice. Calvin told them to avoid arguments. So Knox agreed to a temporary service that was a compromise.

This balance was broken when new refugees arrived. They included Richard Cox, who helped write the Book of Common Prayer. Cox told the Frankfurt authorities about Knox's pamphlet attacking the emperor. The authorities advised Knox to leave. His departure from Frankfurt on March 26, 1555, was his final break with the Church of England.

After returning to Geneva, Knox was chosen to be a minister at a new church. He influenced French Protestants living in Geneva and France. Meanwhile, Elizabeth Bowes wrote to Knox. She asked him to return to Margery in Scotland. He did so in late August. Knox had doubts about the Reformation in Scotland. But he found the country had changed a lot since he was taken prisoner in 1547. He traveled Scotland, preaching reformed ideas and services. Many nobles welcomed him. These included two future regents of Scotland, the Earl of Moray and the Earl of Mar.

The Queen Regent, Mary of Guise, did not act against Knox. But his activities worried church leaders. The Scottish bishops saw him as a threat. They ordered him to appear in Edinburgh on May 15, 1556. So many important people went with him to the trial that the bishops canceled it. Knox was now free to preach openly in Edinburgh. William Keith, the Earl Marischal, was impressed. He urged Knox to write to the Queen Regent. Knox's letter respectfully asked her to support the Reformation and remove the church leaders. Queen Mary saw the letter as a joke and ignored it.

Return to Geneva (1556–1559)

Soon after sending the letter to the Queen Regent, Knox suddenly announced he felt he should return to Geneva. On November 1, 1555, the church in Geneva had chosen Knox as their minister. He decided to take the job. He wrote a final letter of advice to his supporters. He left Scotland with his wife and mother-in-law. He arrived in Geneva on September 13, 1556.

For the next two years, he lived happily in Geneva. He told his friends in England that Geneva was the best place for Protestants to find safety.

Knox was very busy in Geneva. He preached three sermons a week. Each sermon lasted more than two hours. The services used a church order created by Knox and other ministers. The church where he preached, the Église de Notre Dame la Neuve (now called the Auditoire de Calvin), was given by the city for English and Italian churches. Knox's two sons, Nathaniel and Eleazar, were born in Geneva.

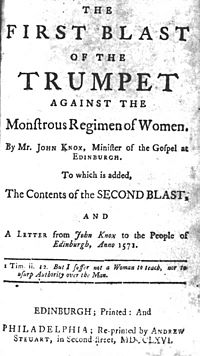

In summer 1558, Knox published his most famous pamphlet. It was called The first blast of the trumpet against the monstruous regiment of women. When he called the rule of women "monstruous," he meant it was "unnatural." The women rulers Knox was thinking of were Queen Mary I of England and Mary of Guise, the Queen Mother of Scotland. This idea was not unusual then. But even Knox knew the pamphlet was dangerous. So he published it without his name. He did not tell Calvin, who denied knowing about it until a year later, that he had written it. In England, the pamphlet was officially banned by the Queen. The pamphlet's impact became complicated later that year. Elizabeth Tudor became Queen of England. Even though Knox had not targeted Elizabeth, he had deeply offended her. She never forgave him.

With a Protestant queen on the throne, the English refugees in Geneva prepared to go home. Knox himself decided to return to Scotland. Before he left, he received many honors. These included being made a free citizen of Geneva. Knox left in January 1559. But he did not arrive in Scotland until May 2, 1559. This was because Elizabeth refused to give him a passport through England.

Revolution and End of the Regency (1559–1560)

Two days after Knox arrived in Edinburgh, he went to Dundee. Many Protestant supporters had gathered there. Knox was declared an outlaw. The Queen Regent called the Protestants to Stirling. Fearing a quick trial and execution, the Protestants went to Perth instead. Perth was a walled town that could be defended. At the church of St John the Baptist, Knox gave a powerful sermon. A small event quickly turned into a riot. A mob poured into the church and destroyed it. The mob then attacked two friaries (Blackfriars and Greyfriars) in the town. They stole gold and silver and smashed religious images.

Mary of Guise gathered loyal nobles and a small French army. She sent the Earl of Argyll and Lord Moray to offer terms and avoid war. She promised not to send French troops into Perth if Protestants left the town. The Protestants agreed. But when the Queen Regent entered Perth, she put Scottish soldiers (paid by the French) there. Lord Argyll and Lord Moray saw this as a betrayal. They both joined Knox, who was now in St Andrews. Knox's return to St Andrews fulfilled his prophecy from the galleys. He had said he would preach in its church again. When he gave a sermon there, the result was the same as in Perth. People engaged in destruction and looting. In June 1559, a Protestant mob, stirred by John Knox's preaching, ransacked the cathedral. The inside of the building was destroyed. The cathedral then fell into disrepair. By 1561, it was abandoned and became a source of building materials for the town.

More Protestant fighters arrived from nearby areas. The Queen Regent retreated to Dunbar. By now, the mob's anger had spread across central Scotland. Her own troops were almost rebelling. On June 30, the Protestant Lords of the Congregation took over Edinburgh. But they could only hold it for a month. Even before they arrived, the mob had already attacked churches and friaries. On July 1, Knox preached from the pulpit of St Giles', the most important church in the capital. The Lords of the Congregation negotiated their withdrawal from Edinburgh. This was done through the Articles of Leith signed on July 25, 1559. Mary of Guise promised freedom of religion.

Knox knew the Queen Regent would ask France for help. So he secretly wrote to William Cecil, Elizabeth's main advisor, asking for English support. Knox secretly sailed to Lindisfarne, off England's northeast coast, in late July. He met with English officials there. Knox was not careful, and news of his mission soon reached Mary of Guise. He returned to Edinburgh. He told the English official he had to go back to his people. He suggested that Henry Balnaves should go to Cecil instead.

When more French troops arrived in Leith, Edinburgh's port, the Protestants responded by taking Edinburgh back. This time, on October 24, 1559, the Scottish nobles officially removed Mary of Guise from her regency. Her secretary, William Maitland of Lethington, joined the Protestant side. He brought his administrative skills. From then on, Maitland handled the political tasks. This freed Knox to focus on being a religious leader. For the last part of the revolution, Maitland appealed to Scottish patriotism. He urged them to fight French control. After the Treaty of Berwick, England finally sent support. By the end of March, a large English army joined the Scottish Protestant forces. Mary of Guise's sudden death in Edinburgh Castle on June 10, 1560, led to the end of fighting. The Treaty of Edinburgh was signed, and French and English troops left Scotland. On July 19, Knox held a National Thanksgiving Service at St Giles'.

Reformation in Scotland (1560–1561)

On August 1, the Scottish Parliament met to decide on religious matters. Knox and five other ministers, all named John, were asked to write a new statement of faith. Within four days, the Scots Confession was given to Parliament. It was voted on and approved. A week later, Parliament passed three laws in one day. The first ended the Pope's power in Scotland. The second condemned all beliefs and practices against the reformed faith. The third banned the celebration of Mass in Scotland. Before Parliament ended, Knox and the other ministers were given the job of organizing the new reformed church, or the Kirk. They worked for several months on the Book of Discipline. This document described how the new church would be organized. During this time, in December 1560, Knox's wife, Margery, died. Knox was left to care for their two sons, who were three and a half and two years old. John Calvin, who had lost his own wife in 1549, sent a letter of sympathy.

Parliament met again on January 15, 1561, to look at the Book of Discipline. The Kirk was to be run democratically. Each church group could choose or reject its own pastor. But once chosen, the pastor could not be fired. Each local church was to support itself as much as possible. Bishops were replaced by ten to twelve "superintendents." The plan also included a national education system. It was based on the idea that everyone should get an education. Some areas of law were placed under church authority. However, Parliament did not approve the plan. This was mainly because of money. The Kirk was to be paid for using the wealth of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. Much of this wealth was now held by the nobles. They did not want to give up their possessions. A final decision on the plan was delayed because Mary, Queen of Scots was about to return.

Knox and Queen Mary (1561–1564)

On August 19, 1561, cannons were fired in Leith to announce Queen Mary's arrival in Scotland. Five days later, she attended Mass in the royal chapel at Holyrood Palace. This led to a protest where one of her servants was pushed. The next day, she announced that religion would not change. She also said her servants should not be attacked. Many nobles accepted this, but not Knox. The next Sunday, he protested from the pulpit of St Giles'.

As a result, just two weeks after her return, Mary called Knox to meet her. She accused him of starting a rebellion against her mother. She also accused him of writing a book against her own power. Knox replied that as long as her people found her rule useful, he would accept her leadership. He noted that Paul the Apostle had lived under Nero's rule. Mary pointed out that he had written against the idea of women ruling at all. He answered that she should not worry about something that had never harmed her. When Mary asked if people had a right to resist their ruler, he said that if rulers went beyond their legal limits, they could be resisted, even with force.

On December 13, 1562, Mary sent for Knox again. This was after he gave a sermon criticizing certain celebrations. Knox thought these celebrations were mocking the Reformation. She said Knox spoke disrespectfully of the Queen to make her seem bad to her people. After Knox explained his sermon, Mary said she did not blame him for different opinions. She asked that in the future, he come to her directly if he heard anything about her he disliked. Despite her friendly gesture, Knox replied that he would keep speaking his beliefs in his sermons. He would not wait to be called by her.

During Easter in 1563, some priests in Ayrshire celebrated Mass. This went against the law. Some Protestants tried to enforce the law themselves by catching these priests. This led Mary to call Knox for the third time. She asked Knox to use his influence to promote religious tolerance. He defended the Protestants' actions. He noted that she was bound to uphold the laws. If she did not, others would. Mary surprised Knox by agreeing that the priests would be brought to justice.

The most dramatic meeting between Mary and Knox happened on June 24, 1563. Mary called Knox to Holyrood. She had heard he was preaching against her planned marriage to Don Carlos, the son of Philip II of Spain. Mary began by scolding Knox. Then she started to cry. "What do you have to do with my marriage?" she asked. And "What are you in this country?" "A subject born within the same, Madam," Knox replied. He said that even though he was not born noble, he had the same duty as any subject to warn of dangers to the country. When Mary started to cry again, he said, "Madam, in God's presence I speak: I never delighted in the weeping of any of God's creatures; yes, I can hardly stand the tears of my own boys whom my own hand corrects, much less can I rejoice in your Majesty's weeping." He added that he would rather endure her tears than stay silent and "betray my Commonwealth." At this, Mary ordered him out of the room.

Knox's last meeting with Mary was caused by an event at Holyrood. While Mary was away from Edinburgh in summer 1563, a crowd forced its way into her private chapel during Mass. During the fight, the priest's life was threatened. As a result, two of the leaders, citizens of Edinburgh, were set for trial on October 24, 1563. To defend these men, Knox sent letters calling the nobles to gather. Mary got one of these letters. She asked her advisors if this was an act of treason. Stewart and Maitland wanted to stay on good terms with both the Kirk and the Queen. They asked Knox to admit he was wrong and settle the matter quietly. Knox refused. He defended himself in front of Mary and the Privy Council. He argued that he had called a legal meeting, not an illegal one. This was part of his duties as a minister of the Kirk. After he left, the council members voted not to charge him with treason.

Final Years in Edinburgh (1564–1572)

On March 26, 1564, Knox married Margaret Stewart. She was the daughter of an old friend, Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord Ochiltree. She was also a distant relative of Queen Mary. Very few details are known about their home life. They had three daughters: Martha, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

When the General Assembly met in June 1564, Knox and Maitland argued about the power of the government. Maitland told Knox to stop causing trouble over Mary's insistence on having Mass. He quoted Martin Luther and John Calvin about obeying rulers. Knox replied that the Bible shows Israel was punished when it followed an unfaithful king. He also said that the European reformers were arguing against Anabaptists who rejected all forms of government. The debate showed that Knox's influence on political events was decreasing. The nobles continued to support Mary.

On July 29, 1565, Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Some Protestant nobles, including James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, rebelled. Knox showed his disapproval while preaching in front of the new King Consort on August 19, 1565. He made comments about ungodly rulers. This caused Darnley to walk out. Knox was then called and forbidden from preaching while the court was in Edinburgh.

On March 9, 1566, Mary's secretary, David Rizzio, was killed by plotters loyal to Darnley. Mary escaped from Edinburgh to Dunbar. By March 18, she returned with a strong force. Knox fled to Kyle in Ayrshire. There, he finished most of his main work, History of the Reformation in Scotland. When he returned to Edinburgh, he found the Protestant nobles divided about what to do with Mary. Lord Darnley had been killed. The Queen almost immediately married the main suspect, the Earl of Bothwell. Because of the suspicion of murder, she was forced to step down and was imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle. Lord Moray became the regent for King James VI. Other old friends of Knox, Lord Argyll and William Kirkcaldy, supported Mary. On July 29, 1567, Knox preached James VI's coronation sermon in Stirling. During this time, Knox strongly spoke against her in his sermons. He even called for her death. However, Mary's life was spared, and she escaped on May 2, 1568.

The fighting in Scotland continued as a civil war. Lord Moray was killed on January 23, 1570. The regent who followed him, the Earl of Lennox, also died violently. On April 30, 1571, the controller of Edinburgh Castle, Kirkcaldy of Grange, ordered all enemies of the Queen to leave the city. But for Knox, his former friend and fellow galley slave, he made an exception. If Knox did not leave, he could stay in Edinburgh, but only as a prisoner in the castle. Knox chose to leave. On May 5, he went to St Andrews. He continued to preach, spoke to students, and worked on his History. In late July 1572, after a truce was called, he returned to Edinburgh. Although very weak and with a faint voice, he continued to preach at St Giles'.

After introducing his successor, James Lawson of Aberdeen, as minister of St Giles' on November 9, Knox returned home for the last time. With his friends and some of the greatest Scottish nobles around him, he asked for the Bible to be read aloud. On his last day, November 24, 1572, his young wife read from Paul's first letter to the Corinthians. A tribute to Knox was given at his grave by James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, the newly elected regent of Scotland: "Here lies one who never feared any flesh." After the churchyard was destroyed in 1633, the exact spot of Knox's grave cannot be found.

John Knox's Legacy

In his will, Knox stated: "None have I corrupted, none have I defrauded; merchandise have I not made." The small amount of money Knox left to his family showed he had not profited from his work in the Kirk. The regent, Lord Morton, asked the General Assembly to keep paying his stipend to his widow for one year after his death. The regent made sure Knox's family was well supported.

Knox was survived by his five children and his second wife. Nathaniel and Eleazar, his two sons by his first wife, went to St John's College, Cambridge. Nathaniel became a Fellow there but died early in 1580. Eleazar became a minister in the Church of England. He served in the parish of Clacton Magna. He also died young and was buried in the chapel of St John's College in 1591. Knox's second wife, Margaret Knox, remarried to Andrew Ker. Knox's three daughters also married: Martha to Alexander Fairlie; Margaret to Zachary Pont; and Elizabeth to John Welsh, a minister of the Kirk.

Knox's death was hardly noticed at the time. Although nobles attended his funeral, no major politician or diplomat mentioned his death in their letters. Mary, Queen of Scots, only mentioned him briefly twice in her letters. However, rulers feared Knox's ideas more than Knox himself. He was a successful reformer. His ideas about reformation greatly influenced the English Puritans. He is also seen as someone who helped the fight for true human freedom. He taught that people had a duty to oppose unfair government to bring about moral and spiritual change. His epitaph reads: "Here lies one who feared God so much that he never feared the face of any man." This refers to Matthew 10:28 in the Bible.

Knox was important not just for ending Roman Catholicism in Scotland. He was also important for making sure that Presbyterianism replaced the old Christian religion, rather than Anglicanism. Thanks to Knox, the Presbyterian church structure was established. However, it took 120 years after his death for this to happen in 1689. Meanwhile, he accepted the situation and was happy to see his friends become bishops and archbishops. He even preached at the inauguration of the Protestant Archbishop of St Andrews John Douglas in 1571. Because of this, Knox is considered the founder of the Presbyterian church. Millions of its members live worldwide today.

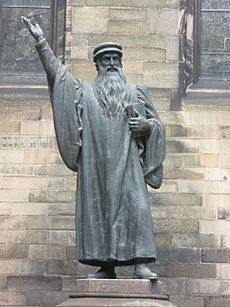

A statue of Knox, by David Watson Stevenson, is in the Hall of Heroes at the National Wallace Monument in Stirling.

Selected Works by John Knox

- An Epistle to the Congregation of the Castle of St Andrews; with a Brief Summary of Balnaves on Justification by Faith (1548)

- A Vindication of the Doctrine that the Sacrifice of the Mass is Idolatry (1550)

- A Godly Letter of Warning or Admonition to the Faithful in London, Newcastle, and Berwick (1554)

- Certain Questions Concerning Obedience to Lawful Magistrates with Answers by Henry Bullinger (1554)

- A Faithful Admonition to the Professors of God's Truth in England (1554)

- A Narrative of the Proceedings and Troubles of the English Congregation at Frankfurt on the Maine (1554–1555)

- A Letter to the Queen Dowager, Regent of Scotland (1556)

- A Letter of Wholesome Counsel Addressed to his Brethren in Scotland (1556)

- The Form of Prayers and Ministration of the Sacraments Used in the English Congregation at Geneva (1556)

- The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women (1558)

- A Letter to the Queen Dowager, Regent of Scotland: Augmented and Explained by the Author (1558)

- The Appellation from the Sentence Pronounced by the Bishops and Clergy: Addressed to the Nobility and Estates of Scotland (1558)

- A Letter Addressed to the Commonalty of Scotland (1558)

- On Predestination in Answer to the Cavillations by an Anabaptist (1560)

- The History of the Reformation in Scotland (1586–1587)

See also

In Spanish: John Knox para niños

In Spanish: John Knox para niños