Scottish Reformation facts for kids

The Scottish Reformation was a huge change in Scotland during the 1500s. It was when Scotland moved away from the Catholic Church and created its own Protestant church, called the Church of Scotland. This was part of a bigger movement happening across Europe at the time.

Starting in the early 1500s, Scottish thinkers and religious leaders began to be inspired by the ideas of Martin Luther, a famous Protestant reformer. In 1560, a powerful group of Scottish nobles, known as the Lords of the Congregation, took charge of the government. They helped pass new laws in the Scottish Reformation Parliament. These laws set up a Protestant belief system and said that the Pope no longer had authority in Scotland. These changes were officially confirmed by James VI a few years later in 1567.

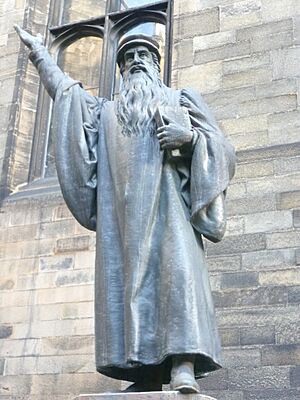

Under the guidance of John Knox, the new Church of Scotland adopted a Presbyterian way of organizing itself. It followed many of the teachings of John Calvin. The Reformation brought big changes to Scottish schools, art, and how people practiced their faith. The Church of Scotland became a source of great national pride. Many Scots even saw their country as a "new Israel," chosen by God.

Contents

- Scotland Before the Reformation

- The Church in Medieval Scotland

- Calls for Change

- Political Changes Leading to Reform

- The Reformation Crisis of 1559-1560

- The Reformation Parliament

- The First Book of Discipline

- The New Church of Scotland

- The Second Reformation Crisis (1567)

- King James VI's Rule

- Catholics in Scotland After the Reformation

- How the Reformation Changed Scotland

- See also

Scotland Before the Reformation

The Church in Medieval Scotland

Christianity first came to Scotland around the 500s. Missionaries from Ireland and, later, from Rome and England helped it spread. By 1192, the Scottish Church became independent from English control. It was seen as a "special daughter" of the Pope in Rome.

The church was organized into different areas called bishoprics. The Bishop of St Andrews became the most important leader. Many local churches, called parishes, were managed by monasteries. By the mid-1500s, about 80% of Scottish parishes were run this way. This often meant less money and support for the local priests.

In 1472, St Andrews became the first archdiocese in Scotland, followed by Glasgow in 1492. During a time when the Pope's power was weaker (1378–1418), Scottish kings gained more control over who became church leaders. Kings often appointed their friends or family members to important church jobs. For example, King James IV made his young son, Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St. Andrews when he was only 11. This gave the king more power but also led to complaints that church leaders were chosen for wealth or family connections, not for their faith.

Everyday Religion in Medieval Scotland

Some historians used to think the church in Scotland before the Reformation was very corrupt and unpopular. However, newer research shows that it met the spiritual needs of many people. Monasteries became less strict, with fewer monks living together. But in towns, new groups of friars, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, became very popular. They focused on preaching and helping people in the community.

Most Scottish towns had only one main church. People believed in Purgatory, a place where souls went after death to be purified before going to Heaven. To help souls get to Heaven faster, people built many small chapels and altars dedicated to saints. They also paid for special prayers and masses. For example, St. Mary's in Dundee had about 48 altars, and St Giles' in Edinburgh had over 50. New ways of showing devotion to Jesus and the Virgin Mary also became popular in the 1400s.

However, there were problems. Many priests held several church jobs at once, which meant some parishes didn't have a dedicated priest. After the Black Death, there was a shortage of clergy. This led to complaints about priests not being well-educated. Also, new ideas challenging the church, called Lollardry, arrived from England and Bohemia in the early 1400s. These followers of John Wycliffe and Jan Hus wanted to reform the church. While some people supported these ideas, it remained a small movement.

Calls for Change

New Ideas: Humanism

In the 1400s, a new way of thinking called Renaissance humanism became popular. Humanists encouraged people to think critically about religion and called for the church to improve. Scottish scholars connected with famous European humanists like Desiderius Erasmus and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples. These thinkers believed the Catholic Church needed to get rid of corruption.

Many Scottish students studied in other European countries. When they returned, they brought these new ideas with them. Humanist scholars were hired to teach at Scotland's new universities in St Andrews, Glasgow, and Aberdeen. This helped Scotland join the wider world of European learning. For example, Hector Boece, who studied in Paris, became the first head of the new University of Aberdeen in 1497.

Important Scottish thinkers like John Mair and Robert Reid also played a role. Reid, for instance, helped bring an Italian humanist, Giovanni Ferrario, to teach in Scotland. These scholars and their ideas helped create a desire for change within the church and society.

Lutheranism Arrives

From the 1520s, the ideas of Martin Luther began to reach Scotland. Books with Lutheran teachings were shared in towns along the east coast. In 1525, the Scottish Parliament tried to stop these books from coming into the country. However, in 1527, English officials noted that Scottish merchants were bringing William Tyndale's new English translation of the Bible to Scotland.

In 1528, a nobleman named Patrick Hamilton became the first Protestant to face severe punishment in Scotland. He had learned about Lutheran ideas while studying in Germany. He was put to death for his beliefs outside St Salvator's College in Saint Andrews. His death, however, made more people interested in these new ideas. Church leaders were even warned that "the smoke of Maister Patrik Hammyltoun has infected as many as it blew upon," meaning his death only spread his ideas further.

Political Changes Leading to Reform

King James V's Reign

When King James V began his personal rule in 1528, he chose not to make big changes to the church like Henry VIII was doing in England. Instead, James stayed loyal to Rome. He also heavily taxed the church, collecting a lot of money. These actions weakened the church's standing and its finances.

The church itself faced disagreements between powerful archbishops. In 1536, a church council met but failed to make big reforms or unite against the new Protestant ideas. After Patrick Hamilton's death, some other people were also put to death for their beliefs. However, King James V didn't want widespread violence.

More and more nobles and landowners, especially in areas like Fife, started to support church reform. Important leaders included Alexander Cunningham, 5th Earl of Glencairn and John Erskine of Dun. In 1541, Parliament passed laws to protect traditional Catholic practices, like the Mass and prayers to the Virgin Mary.

The "Rough Wooing" and French Influence

King James V died in 1542, leaving his baby daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, as queen. This meant Scotland would be ruled by others for many years. At first, the country was divided. Some nobles favored an alliance with France, led by Cardinal Beaton and Mary's mother, Mary of Guise. Others wanted to be closer to England.

Initially, Earl of Arran became regent and supported religious reform. In 1543, a law was passed allowing people to read the Bible in their own language. There was a plan for Mary to marry Edward, the son of England's King Henry VIII. But this led to anger in Scotland, and Cardinal Beaton took power. He stopped the reforms and the English marriage plan, which made the English very angry.

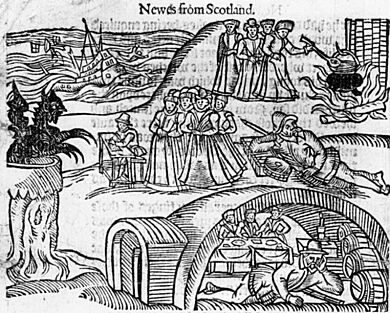

England then invaded Scotland to force the marriage, an event known as the "rough wooing." This caused a lot of damage in southeastern Scotland. In 1546, a preacher named George Wishart was put to death for his Protestant beliefs. His supporters then assassinated Cardinal Beaton and took over St Andrews Castle. They were eventually defeated with help from French forces. Survivors, including John Knox, were forced to become galley slaves, which increased Scottish dislike for the French.

In 1547, the English invaded again and defeated the Scots at Pinkie. They occupied parts of southeastern Scotland. This English presence encouraged the Protestant cause, as they distributed Bibles and Protestant books. To fight back, Scotland sought help from France. The price was that young Queen Mary was betrothed to the French prince, Francis II. She left for France in 1548 to be raised there. By 1554, Mary's mother, Mary of Guise, became regent, strengthening French control.

Mary of Guise's Leadership

As regent (1554–1560), Mary of Guise made sure France had a strong influence in Scotland. She placed Frenchmen in important government roles. At first, she allowed some religious freedom for Protestants, hoping to gain their support against England. England was then ruled by the Catholic Queen Mary Tudor.

However, when Mary Queen of Scots married the French prince in 1558, many Scots feared Scotland would become a French province. The arrival of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth to the English throne in 1558 gave Scottish reformers new hope. It created a clear religious divide between Protestant England and Catholic-leaning Scotland.

Church Councils Try to Reform

The Catholic Church in Scotland tried to address some of the criticisms against it. Archbishop John Hamilton held several church councils between 1549 and 1559. These councils admitted that the spread of Protestant ideas was due to "corruption of morals" and "ignorance" among church leaders.

They tried to stop priests from having multiple jobs or living immoral lives. They also ordered bishops and priests to preach more often and for monks to attend university. But by 1552, it was clear that little had changed. Many priests still lacked knowledge of the Bible, and church attendance remained low.

Protestantism Grows Stronger

Protestantism continued to grow during this time. Protestants began to form "privy kirks" (secret churches) where they met for worship, moving away from the official Catholic Church. Their organization was strong enough that John Knox returned to Scotland in 1555. He led Protestant services and preached to these secret groups.

Knox urged Protestants to openly declare their faith and not pretend to be Catholic. Even though he was offered protection, he returned to Geneva in 1556. In his absence, the movement was led by nobles who had become Protestant. These included Lord Lorne and Lord James Stewart, who was King James V's illegitimate son.

In 1557, these nobles signed a "first bond," promising to support each other against anyone who tried to stop their religious freedom. This group became known as the Lords of the Congregation. They directly challenged the existing government and the Catholic Church.

The Reformation Crisis of 1559-1560

On January 1, 1559, a message called the Beggars' Summons appeared on church doors. It warned friars that their property should go to the poor. This message was popular with townspeople who had complaints against the friars. John Knox returned to Scotland and preached in Perth on May 11. His sermon inspired the people to remove religious statues and altars from the church. They also raided local monasteries.

The regent, Mary of Guise, sent soldiers to restore order. But the Lords of the Congregation gathered their own forces. After some tense negotiations, key nobles like Argyll and James Stuart switched sides to support the Protestant cause. This led to armed conflict.

Protestants began to take control in many towns and regions. They removed Catholic symbols from churches and appointed Protestant preachers. This happened even in places like Aberdeen and St. Andrews. In June, Mary of Guise sent a French army, but it was forced to retreat. Edinburgh then fell to the Lords of the Congregation.

The Lords asked England for help, while Mary of Guise asked France. English agents helped Earl of Arran return safely to Scotland to lead the Lords. In October, the regent was temporarily removed from power. Mary of Guise's forces continued to advance, but the arrival of the English fleet in January 1560 changed everything. The French retreated to Leith near Edinburgh.

England and the Lords agreed to work together in February 1560. An English army then besieged the French in Leith. Mary of Guise became ill and died in June. With no more help coming, the French began talks. The Treaty of Edinburgh (July 5, 1560) meant both French and English troops left Scotland. This left the Protestant Lords in control. They recognized Mary Queen of Scots and her husband, Francis II of France, as monarchs. They were also allowed to hold a parliament, but it was not supposed to discuss religion.

The Reformation Parliament

The Parliament of Scotland met in Edinburgh on August 1, 1560. Many nobles, bishops, and landowners attended. Even though the Treaty of Edinburgh said they shouldn't discuss religion, on August 17, Parliament approved a new Protestant statement of faith called the Scots Confession. On August 24, they passed three laws that officially ended the old Catholic faith in Scotland.

These laws cancelled all previous acts that didn't agree with the new Protestant beliefs. They also said that only two sacraments (Baptism and Communion) could be performed by Protestant preachers. Celebrating the Catholic Mass became illegal, with severe penalties, and the Pope's authority in Scotland was rejected. However, Queen Mary refused to officially approve these laws, so the new church existed in a state of legal uncertainty for a while.

The First Book of Discipline

The Lords of the Congregation wanted Parliament to consider a "Book of Reformation," mostly written by John Knox. They weren't completely happy with it, so a committee of "six Johns" (including Knox) was formed to revise it. This revised document, known as the First Book of Discipline, was discussed by a smaller group of nobles and landowners in January 1561. It was approved by individuals, but not as a whole.

The Book suggested a plan for a reformed church in every parish. It proposed using the wealth of the old Catholic Church to pay for ministers, a school system, university education, and help for the poor. However, this idea for using church wealth was rejected. Instead, a new law kept two-thirds of the church's money with its current owners. The remaining third was split between the Crown and the new church's needs. As a result, the education plan was abandoned, ministers were poorly paid, and the church didn't have enough money.

The New Church of Scotland

What People Believed: The Scots Confession

John Knox and five other ministers wrote the Scots Confession in just four days. It had 25 chapters, similar to the Apostles' Creed, focusing on God the Father, Jesus Christ, the Church, and the end times. This Confession was the main statement of belief for the Church of Scotland until 1647.

The Confession was strongly Calvinist. It emphasized God's "inscrutable providence," meaning God had planned everything. It also stressed that humanity was deeply flawed and deserved eternal punishment, but God mercifully chose some for salvation through grace alone. It rejected the Catholic belief of transubstantiation (that bread and wine literally become the body and blood of Christ) but still believed in the real presence of Christ in Communion. It focused on explaining the new faith simply, rather than harshly criticizing Catholicism. It saw the Church of Scotland as a worldwide community of God's chosen people.

How People Worshipped: New Services

The Reformation completely changed how people worshipped. Instead of many Catholic holy days and Masses, Sunday became the main day of worship. People were expected to attend regularly. Latin was replaced by the local language. Congregational psalm singing took the place of complex music sung by trained choirs.

There was a strong focus on the Bible and sermons, which often lasted over an hour. Many parishes without a minister had "readers services" with psalms, prayers, and Bible readings. The Geneva Bible was widely used. John Knox wrote his own Book of Common Order, which became the standard for services in 1562. It was reprinted with the Confession and psalms in 1564 and used until 1643. A Gaelic translation of the Book of Common Order was printed in 1563, the first book ever printed in Gaelic.

How the Church Was Organized

The First Book of Discipline planned for about 1,080 parishes to have reformed ministers. By 1561, 240 positions were filled, growing to over 1,000 by 1574. Most were in the south and east. The Highlands had few ministers, and even fewer spoke Gaelic. Universities couldn't train enough ministers, so many (over three-quarters in 1574) were "readers" rather than fully qualified ministers. Most of these were former Catholic clergy.

The old system of thirteen dioceses was meant to be replaced by ten new districts, each led by a superintendent. This plan was complicated because three Catholic bishops became Protestant and kept their jobs. Few superintendents were appointed, and temporary commissioners filled the gaps. By 1576, the General Assembly recognized five types of church leaders: archbishops, bishops, superintendents, commissioners, and visitors.

Alongside these leaders, there was a system of church courts called kirk sessions and presbyteries. These courts handled discipline and administration. By the 1590s, Scotland had about 50 presbyteries, each with about 20 ministers. Above them were synods, and at the top was the General Assembly. The kirk sessions gave local landowners significant power as church elders.

Continuing Changes

In the 1560s, most people were likely still Catholic. The new church found it hard to reach the Highlands and Islands. However, the change to Protestantism was gradual and involved little violence compared to other countries. Monasteries were not immediately shut down but were allowed to slowly fade away. Before 1573, no church leaders lost their jobs just for not converting.

The focus on the parish church meant many chapels, monasteries, and cathedrals were no longer used. Many fell into ruin, or their stones were taken to build local houses, like at St Andrews Cathedral.

The Second Reformation Crisis (1567)

When her husband, Francis II, died in 1560, Mary, then 19, returned to Scotland to rule. She was allowed to practice her Catholic faith privately and didn't try to force Catholicism on her subjects. However, her six-year reign was full of problems caused by rivalries among nobles.

After the murder of her secretary, David Riccio, her unpopular husband, Lord Darnley, was also killed. Mary then married the Earl of Bothwell, who was suspected in Darnley's murder. Opposition to Bothwell led to a group of nobles forming the Confederate Lords. Historians call the events of 1567 a "second Reformation crisis."

Mary and Bothwell faced the Lords at Carberry Hill on June 15, 1567, but their forces abandoned them. Bothwell fled, and Mary was imprisoned. Ten days later, the General Assembly met to remove "superstition and idolatry." The Reformation settlement of 1567 was much more strongly Calvinist than the one in 1560. The Assembly planned reforms, including confirming the 1560 laws, better support for ministers, and a closer relationship with Parliament. A Parliament in December officially approved the laws passed by the Reformation Parliament. The new religious system was developed further throughout the 1570s during a time of civil war and changing regents.

King James VI's Rule

In July 1567, Mary was forced to give up her throne to her 13-month-old son, James VI. James was raised as a Protestant. Scotland was ruled by a series of regents, starting with Moray, until James began to rule on his own in 1581. Mary later escaped and tried to regain her throne by force. After her defeat in 1568, she fled to England, leaving her son in the care of his Protestant supporters.

In Scotland, the King's Party fought a civil war against Mary's supporters. This ended in 1573. In 1578, a Second Book of Discipline was adopted, which made the church structure even more clearly Presbyterian.

In England, Mary became a focus for Catholic plots and was eventually put to death for treason in 1587. King James VI believed in Calvinist teachings but strongly supported having bishops in the church. He resisted the idea that the Church of Scotland should be completely independent or interfere in government. He used his power to control when and where the General Assembly met, limiting the influence of more radical clergy. By 1600, he had appointed three bishops, and by the end of his reign, there were 11 bishops. This restored the system of bishops, though many in the church still preferred Presbyterianism.

Catholics in Scotland After the Reformation

Even though it was officially illegal, the Catholic faith survived in some parts of Scotland. Church leaders played a smaller role, and local nobles or landowners often protected Catholic communities. In places like South Uist and the northeast, where the Earl of Huntly was powerful, Catholic practices continued openly. Nobles were often hesitant to persecute each other over religion due to strong personal connections. An English report in 1600 suggested that about a third of nobles and gentry still had Catholic sympathies.

In most of Scotland, Catholicism became a private faith, practiced secretly in homes and connected by family ties. Women often played a key role in keeping the faith alive, transforming their homes into centers of religious activity and offering safe places for priests.

Because the Reformation took over the existing church buildings and wealth, it was very difficult for the Catholic Church to recover. After Mary's cause failed in the civil wars of the 1570s, the Catholic hierarchy began to treat Scotland as a mission area. The Jesuits, a leading order of the Counter-Reformation, initially showed little interest in Scotland. Their efforts were also limited by rivalries among different religious orders. A small group of Scots, often from the Crichton family, joined the Jesuit order and returned to Scotland to try and convert people. They mainly focused on the royal court, which led them into political plots, often ignoring the majority of ordinary Scottish Catholics.

How the Reformation Changed Scotland

Education for All

Humanists and Protestant reformers both wanted to expand education. The First Book of Discipline proposed a school in every parish, but this was too expensive. In towns, old schools continued, and new ones became reformed grammar schools or parish schools. Schools were supported by church funds, local landowners, town councils, and parents who could pay. Kirk sessions (church courts) inspected schools to check teaching quality and religious beliefs.

Many "adventure schools" also existed, sometimes filling a local need. Teachers often held other jobs, like church clerks. At their best, schools taught religious instruction, Latin, French, classical literature, and sports.

Scotland's universities were reformed by Andrew Melville, who returned from Geneva to lead the University of Glasgow in 1574. He was a brilliant scholar who had studied in Paris and Geneva. Influenced by new ideas, he emphasized simpler logic and gave languages and sciences the same importance as philosophy. He introduced specialist teachers, replacing the old system where one tutor taught everything. Greek became compulsory in the first year, followed by other ancient languages. Glasgow, which had been struggling, saw a large increase in students.

Melville also helped rebuild Marischal College, Aberdeen, and became Principal of St Mary's College, St Andrews, in 1580. The University of Edinburgh grew out of public lectures started in the 1540s and became a university in 1582. These changes revitalized all Scottish universities, offering an education as good as anywhere in Europe.

Literature and Plays

Medieval Scotland likely had its own religious plays, often performed by craft guilds, but no texts survive. Laws were passed against folk plays in 1555 and against religious plays based on the Bible in 1575 by the General Assembly. However, attempts to ban folk plays were less successful than once thought, and they continued into the 1600s. The church did allow some plays, especially in schools, if they served educational purposes, like a comedy about the Parable of the Prodigal Son in St. Andrews in 1574.

More formal plays included those by James Wedderburn, who wrote anti-Catholic plays around 1540. David Lyndsay (c. 1486–1555), a diplomat and poet, wrote The Thrie Estaitis in 1540, which criticized corruption in the church and state. This is the only complete play from before the Reformation that still exists. George Buchanan (1506–1582) had a big influence on European theater with his Latin plays, but his impact in Scotland was limited because he wrote in Latin.

Unlike England, Scotland didn't develop a system of professional theater companies. However, James VI showed interest in drama by arranging for an English company to perform in 1599. The church also discouraged poetry that wasn't religious. Still, poets like Richard Maitland and Alexander Hume wrote various types of verses. Alexander Scott's short songs paved the way for the Castalian Band poets during James VI's reign.

Art and Creativity

The Reformation had a huge impact on church art. Many medieval stained glass windows, religious sculptures, and paintings were destroyed. The only significant pre-Reformation stained glass left in Scotland is a window in the Magdalen Chapel in Edinburgh, completed in 1544. Wood carvings can still be seen at King's College, Aberdeen and Dunblane Cathedral. In the West Highlands, where there were skilled stone carvers, the Reformation led to a decline in their craft.

Historians suggest the Scottish Reformation may have limited public displays of art, pushing creativity towards more simple forms. With the loss of church support, artists and craftsmen turned to wealthy individuals for work. This led to a flourishing of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls. Many private homes of merchants, landowners, and lords were decorated with detailed and colorful patterns and scenes. Over 100 examples still exist today. These were created by Scottish artists using European design books, often including symbols from mythology, heraldry, and moral lessons. Early examples include Kinneil House (1550s) and Pinkie House (1621).

Church Buildings Changed

The Reformation completely changed church architecture in Scotland. Protestants rejected fancy decorations in places of worship, believing elaborate buildings were unnecessary for their services. This led to the widespread destruction of medieval church furnishings and ornaments. New churches were built, and old ones were changed to suit reformed services. The pulpit became the central point, as preaching was key to worship.

Many early churches were simple rectangular buildings, a style that continued into the 1600s, like at Dunnottar Castle (1580s) and Greenock's Old West Kirk (1591). These churches often had windows only on the south wall. Some churches used local stone, and a few added wooden steeples, like at Burntisland (1592). Greyfriars, Edinburgh (1602–1620) used a rectangular layout with a Gothic style.

A common design for adapting existing churches was the T-shaped plan. This allowed the most people to be close to the pulpit. Examples include Kemback and Prestonpans after 1595. This plan was used into the 1600s, as seen at Weem (1600) and New Cumnock, Ayreshire (1657). Later, some churches used a Greek cross plan, like Cawdor (1619), but often one arm was closed off, making them effectively T-plan churches.

Music in the Church

The Reformation severely impacted church music. Song schools in abbeys and cathedrals closed, choirs were disbanded, music books destroyed, and organs removed from churches. Early Scottish reformers, influenced by Lutheranism, tried to include some Catholic music traditions, using Latin hymns and local songs. The most famous example was The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567), spiritual versions of popular songs. Though not officially adopted by the church, they remained popular.

Later, the Calvinist ideas that dominated the Scottish Reformation were much stricter about music. They focused on biblical texts, especially the Psalms. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 was created by the Church Assembly. It used works by French and English musicians. The goal was to have a unique tune for each psalm, but eventually, common tunes were used for psalms with the same rhythm. Since entire congregations sang these psalms, the music was kept simple.

During his reign, James VI tried to bring back song schools. A 1579 law required large towns to set up "ane sang scuill" (a song school). Five new schools opened within four years, and by 1633, there were at least 25. Polyphony (music with multiple independent melodies) was included in Psalter editions from 1625, but usually, the congregation sang the main melody while trained singers sang other parts. The triumph of the Presbyterians in 1638 ended polyphony, and a new, simpler psalter was published in 1650. By the late 1600s, these works formed the basic music sung in the Church of Scotland.

Women's Roles and Lives

Early modern Scotland was a patriarchal society, meaning men held most of the authority. After the 1560s, the new marriage service emphasized that a wife was "in subjection and under governance of her husband." In politics, this idea was challenged by female regents like Margaret Tudor and Mary of Guise, and by Mary, Queen of Scots ruling as queen from 1561. John Knox even wrote a book, The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women (1558), arguing against female rulers. Most nobles accepted Mary as queen, but these tensions may have contributed to the difficulties of her reign.

Before the Reformation, getting married to a relative often required special permission from the Pope. This permission could sometimes be used to end a marriage later. Divorce, as we know it, didn't exist, though separations were allowed in extreme cases. Under the reformed Church of Scotland, divorce became possible for reasons like unfaithfulness or a spouse leaving the family. Scotland was one of the first countries to allow desertion as a legal reason for divorce, and divorce cases were pursued by people from different social classes.

After the Reformation, there was a stronger focus on women taking personal moral responsibility, especially as wives and mothers. Protestantism encouraged women to learn and understand religious teachings and even to read the Bible themselves. However, most people still believed girls shouldn't receive the same academic education as boys. In lower social classes, girls benefited from the expansion of parish schools, but they were often fewer in number, taught separately, for shorter periods, and to a lower level. They usually learned reading, sewing, and knitting, but not writing. Illiteracy rates for women remained high, around 85% by 1750, compared to 35% for men. Among noble families, many women were well-educated, with Queen Mary being a prime example.

Church attendance was important for many women. While women were largely excluded from church administration, in some parishes, female heads of households could vote on new ministers. In the post-Reformation period, the church courts (kirk sessions) disciplined women for various behaviors. These changing attitudes might partly explain the witch hunts that happened after the Reformation, where women were the main victims.

Everyday Faith and Beliefs

Scottish Protestantism centered on the Bible, seen as God's perfect word and the main source of moral guidance. Many Bibles were large, illustrated, and valuable. The Geneva Bible was commonly used until the Kirk adopted the Authorised King James Version in 1611. The first Scottish version was printed in 1633, but the Geneva Bible remained popular. Bibles sometimes became objects of superstition, used for telling the future.

Church discipline was very important in Reformed Protestantism, especially in the 1600s. Kirk sessions could use religious punishments, like excommunication or refusing baptism, to enforce good behavior. For more serious moral issues, they worked with local magistrates, similar to a system used in Geneva. Public celebrations were viewed with suspicion. From the late 1600s, kirk sessions tried to stop activities like well-dressing, bonfires, guising (dressing up), and dancing.

In the late Middle Ages, there were a few cases of people being accused of witchcraft. But the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft a crime punishable by death. The first major trials under this new law were the North Berwick witch trials, starting in 1589. King James VI was very involved as a "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and wrote a book defending witch-hunting in 1597. However, he later became more doubtful and took steps to limit prosecutions. An estimated 4,000 to 6,000 people, mostly from the Scottish Lowlands, were tried for witchcraft during this period, a much higher rate than in England. About 75% of those accused were women, and over 1,500 people were put to death.

A New Scottish Identity

The Church of Scotland that developed after 1560 came to represent all of Scotland. It became a source of national pride, often compared favorably to the less reformed church in England. Some historians suggest that because Scotland had lost some of its international standing, Scots emphasized their religious achievements. A new idea developed that Scotland had a special agreement, or covenant, with God.

Many Scots saw their country as a "new Israel" and themselves as a holy people fighting against evil, which they identified with the Pope and the Catholic Church. Events like the 1572 Massacre of St Bartholomew in France and the Spanish Armada in 1588 reinforced these views, showing that Protestantism was under threat. These ideas were spread through the first Protestant histories, like Knox's History of the Reformation and George Buchanan's Rerum Scoticarum Historia. This period also saw a rise in patriotic literature, helped by popular printing. Old Scottish poems and plays found new audiences.

See also

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |