Music in early modern Scotland facts for kids

Music in early modern Scotland covers all kinds of music made in Scotland from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. During this time, Scottish kings and queens loved music. They supported both religious and everyday music. Some rulers were even good musicians themselves!

In the 1500s, playing an instrument and singing became important skills for noble men and women. But when King James VI moved to London in 1603 to rule England too, Scotland lost a big supporter of music. The Chapel Royal, Stirling Castle fell apart, and there was less money for musicians.

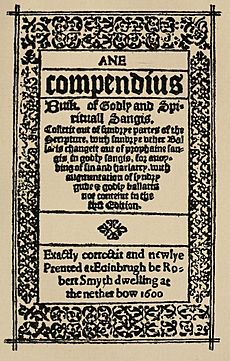

Important composers of this time included Robert Carver and David Peebles. The early Reformation (a big change in religion) was okay with using old Catholic songs and local tunes in church. The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567) is a good example of this. However, a stricter form of Protestantism called Calvinism later took over. This led to song schools closing, choirs being broken up, organs being removed from churches, and music books being destroyed. People then focused on singing Psalms (religious songs from the Bible) without instruments.

Even though the Kirk (the Scottish church) tried to stop popular everyday music, it kept going. This period saw the rise of the highland bagpipes and the fiddle. Old Ballads (story-songs), some from the Middle Ages, were passed down by word of mouth.

Later, people like Allan Ramsay wanted to create a special Scottish musical style. He worked with an Italian musician, Lorenzo Bocchi, on Scotland's first opera, the Gentle Shepherd. Edinburgh became a center for music. Composers started mixing Scottish tunes with Italian music styles. By the mid-1700s, many Italian musicians lived in Scotland. Scottish composers also began to become famous.

Contents

Music for Kings, Queens, and Nobles

During this time, Scotland's royal court, like other European courts, enjoyed music with instruments. King James V loved church music. He was also a skilled lute player. He brought French songs and groups of viol players to his court. Sadly, most of this everyday court music is now lost.

When Mary, Queen of Scots returned from France in 1561, she was Catholic. This gave new life to the Chapel Royal choir. But because church organs were destroyed in Scotland, musicians had to use trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes, and tabors to play for church services. Mary, like her father, played the lute and virginals. She was also a great singer. She brought French musicians, like lute and viol players, with her.

King James VI (who ruled from 1566 to 1625) was a big supporter of all arts. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594. The choir sang for important events, like the baptism of his son Henry. He also had lute players for his own fun, just like other members of his family.

When James moved to England in 1603 to become King of England, Scotland lost a major source of music support. The Chapel Royal in Scotland began to fall apart. The royal court in London became the main place for royal music. Holyrood Abbey was fixed up for King Charles I's visit in 1633. It became a church again when King Charles II returned to power. It was also a worship center when James VII lived there in the early 1680s. But a mob attacked it in 1688 during the Glorious Revolution.

These musical trends spread to noble families. They hired musicians, including viol and lute players. Like in other parts of Europe, being able to play music became an important skill for noble men and women. Musicians taught the children of the household, both boys and girls. Records from the late 1500s and early 1600s show lessons in various instruments and singing. Families also bought sheet music and instruments like virginals and harpsichords.

In the Highlands, clan chiefs still hired harpists and, more and more, pipers. These musicians were like poets and storytellers. Their skill in praising ancestors was key to showing a clan's importance. The first printed collection of everyday music in Scotland was by John Forbes in Aberdeen in 1662. It was called Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols, also known as Forbes' Cantus. It was printed three times in 20 years and had 77 songs, with 25 of them being Scottish.

Church Music in Scotland

The most important Scottish composer in the early 1500s was Robert Carver (around 1488–1558). He was a priest at Scone Abbey. His complex music could only be performed by a large, well-trained choir, like the one at the Scottish Chapel Royal. King James V also supported other musicians, including David Peebles (around 1510–1579?). His most famous work is "Si quis diligit me," a song for four voices. These were likely just two of many talented composers from this time whose music is mostly lost today. Much of the church music that survived from the early 1500s is thanks to Thomas Wode (died 1590). He was a church official who copied music from sources that are now lost. Others continued his work after he died.

The Scottish Reformation greatly changed church music. Song schools in churches were closed. Choirs were broken up. Music books were destroyed, and organs were taken out of churches. The early Scottish Reformation, influenced by Lutheranism, tried to keep some Catholic music traditions. It used Latin hymns and local songs. The most important example of this in Scotland was The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567). These were spiritual versions of popular songs, written by the brothers James, John, and Robert Wedderburn. The church never officially used them, but they stayed popular and were reprinted from the 1540s to the 1620s.

Later, Calvinism became the main form of Protestantism in Scotland. It wanted to replace Catholic music and popular songs with versions of the Psalms that were set to a rhythm. The church believed these were more biblical. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 was created by the Church Assembly. It used ideas from French musician Clément Marot and English writers. The goal was to have a unique tune for each psalm. But out of 150 psalms, only 105 had their own tunes. In the 1600s, common tunes that could be used for psalms with the same rhythm became more popular. Since whole groups of people would now sing these psalms, not just trained choirs, the music needed to be simple. Most church songs were written in a homophonic style, meaning all parts sang the same rhythm.

During his rule, James VI tried to bring back song schools. A law was passed in 1579, telling big towns to set up "a song school with a master good enough to teach young people the science of music." Five new schools opened within four years. By 1633, there were at least 25. Most towns without song schools taught music in their regular schools.

More complex music was added to new versions of the Psalter from 1625. But in the few places where these were used, the church group sang the main tune. Trained singers sang the other parts. However, when the Presbyterians gained power in 1638, complex music ended. A new psalter with common rhythms, but without tunes, was published in 1650. In 1666, The Twelve Tunes for the Church of Scotland, composed in Four Parts (which actually had 14 tunes) was first published in Aberdeen. It was made to be used with the 1650 Psalter. This book was printed five times by 1720. By the late 1600s, these two books were the main source of psalm songs sung in the Scottish church.

Popular Music in Scotland

Everyday popular music continued, even though the Kirk, especially in the Lowlands, tried to stop dancing and events like penny weddings where music was played. Many musicians kept performing, including the fiddler Pattie Birnie and the piper Habbie Simpson (1550–1620).

The first clear mention of the Highland bagpipes is from a French history book. It talks about them being used at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547. George Buchanan said that bagpipes had replaced trumpets on the battlefield. This period saw the creation of ceòl mór (the great music) for the bagpipe. This music showed its military roots, with battle tunes, marches, gathering calls, salutes, and sad laments. In the early 1600s, piping families grew in the Highlands. These included the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors, and the Mackays of Gairloch. There is also proof that the fiddle was used in the Highlands. Martin Martin wrote in his book A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland (1703) that he knew of 18 fiddle players in Lewis alone.

There is evidence of ballads from this time. Some might be from the late Middle Ages. They tell stories about events and people from as far back as the 1200s. Examples include "Sir Patrick Spens" and "Thomas the Rhymer". However, we don't have written proof of them until the 1700s. Scottish ballads are special because they include old, pre-Christian ideas, like fairies in the Scottish ballad "Tam Lin". They were passed down by word of mouth.

Interest in folk songs grew in the 1700s. This led collectors like Bishop Thomas Percy to publish books of popular ballads. The strict rules against everyday music and dancing began to relax between about 1715 and 1725. This led to many new music publications. These included broadsheets (single sheets of paper with songs) and music collections. Examples are the poet Allan Ramsay's song collection The Tea Table Miscellany (1723) and William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius (1725).

Classical Music in Scotland

From the late 1600s, music became less of a hobby for rich people. It became more of a job for professional musicians. People enjoyed music in quiet concert halls, not just as background entertainment in royal homes. The German flute likely came to Scotland around the end of the 1600s.

The Italian style of classical music probably first arrived in Scotland with Lorenzo Bocchi. He was an Italian cellist and composer who came to Scotland in the 1720s. He introduced the cello to the country. He also created music for Lowland Scots songs. He might have helped with Scotland's first opera, The Gentle Shepherd, which had words by Allan Ramsay.

Music in Edinburgh grew thanks to people like Sir John Clerk of Penicuik. He was a merchant, but also a famous composer, violinist, and harpsichord player. The growth of music in the capital city was marked by the creation of the Musical Society of Edinburgh in 1728.

A group of Scottish composers started to follow Allan Ramsay's idea to "own and refine" their own music. They created what is called the "Scots drawing room style." They took mostly Lowland Scottish tunes and added simple bass lines and other features from Italian music. This made the music popular with middle-class audiences. This style became more popular when major Scottish composers like James Oswald and William McGibbon joined in around 1740. Oswald's Curious Collection of Scottish Songs (1740) was one of the first to include Gaelic tunes alongside Lowland ones. This became a common trend by the mid-1700s and helped create a single Scottish musical identity.

However, as styles changed, fewer collections of only Scottish tunes were published. Instead, Scottish tunes were included in bigger British collections. By the mid-1700s, Italian musicians lived in Scotland as composers and performers. These included Nicolò Pasquali, Giusto Tenducci, and Fransesco Barsanti. Thomas Erskine, 6th Earl of Kellie (1732–81) was one of the most important British composers of his time. He was also the first Scot known to have written a symphony.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |