Battle of Pinkie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Pinkie |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Rough Wooing | |||||||

River Esk and Inveresk Church at Musselburgh |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 16,800 30 warships |

18,000 to 22,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200–600 killed | 5,000 to 6,000 killed 2,000 captured |

||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL15 | ||||||

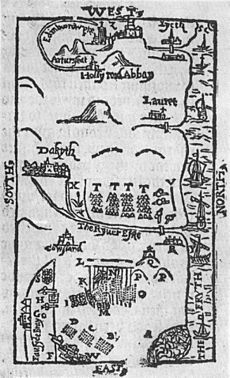

The Battle of Pinkie, also called the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh, happened on September 10, 1547. It took place near Musselburgh, Scotland, by the River Esk. This was the last big battle fought between Scotland and England. It was part of a conflict known as the Rough Wooing. Many people consider it the first modern battle in the British Isles. It was a terrible defeat for Scotland, where it became known as "Black Saturday." An English soldier named William Patten wrote a detailed book about the battle. He was there and saw everything.

Contents

Why the Battle of Pinkie Happened

In the last years of his rule, King Henry VIII of England wanted Scotland to join his country. He hoped to do this by marrying his young son, Edward VI, to the infant Scottish Queen, Mary, Queen of Scots. When peaceful talks failed, and Scotland planned to team up with France, Henry VIII started a war. This war is known as the Rough Wooing.

The war also had a religious side. Some Scots did not want to join England if it meant changing their church beliefs. During the battle, Scottish soldiers insulted the English. They called them "heretics," meaning people with different religious beliefs.

When Henry VIII died in 1547, Edward Seymour became a powerful leader in England. He was the uncle of the new young king, Edward VI. Seymour continued the plan to force Scotland into an alliance. He wanted Mary to marry Edward. He also wanted Scotland to accept the English Church's new ways. In early September, he led a strong English army into Scotland. A large fleet of ships supported his army.

The Scottish leader, the Earl of Arran, knew the English were coming. His representative in London had warned him.

The Armies and Their Plans

Somerset's English army had different types of soldiers. Some were traditional county soldiers with longbows and bills. These were like the soldiers from 30 years before. But Somerset also had hundreds of German soldiers who used arquebuses (early firearms). He also had many cannons and 6,000 cavalry (soldiers on horseback). This included Spanish and Italian horsemen.

William Patten, an English officer, wrote that the army had 16,800 fighters. It also had 1,400 "pioneers" or workers. Somerset moved his army along the east coast of Scotland. This way, his ships could easily bring supplies. Scottish Border Reivers (raiders) bothered his troops but could not stop them.

The Earl of Arran gathered a large Scottish army to stop the English. Most of his soldiers were pikemen (soldiers with long spears). He also had archers from the Highlands. Arran had many cannons, but they were not as easy to move as the English ones.

The Scottish cavalry had only 2,000 lightly armed riders. Many of these were Borderers, who were not always reliable. The Earl of Arran, the Earl of Angus, and the Earl of Huntly led the Scottish foot soldiers. The Scottish army had about 22,000 to 23,000 men.

Arran placed his army on the west side of the River Esk. This blocked Somerset's path. The Firth of Forth (a sea inlet) was on his left side. A large swamp protected his right side. They built some defenses and placed cannons there. Some guns pointed towards the sea to keep English warships away.

Events Before the Battle

On September 9, part of Somerset's army took Falside Hill. Falside Castle nearby offered little resistance. It was about 3 miles (5 km) east of Arran's main position.

In an old-fashioned move, the Earl of Home led 1,500 Scottish horsemen near the English camp. He challenged an equal number of English cavalry to fight. Lord Grey of Wilton accepted the challenge. He led 1,000 heavily armored English horsemen and 500 lighter ones. The Scottish horsemen were badly beaten. They were chased for 3 miles (5 km) to the west. This fight cost Arran most of his cavalry. The Scots lost about 800 men. Lord Home was badly hurt, and his sons were taken prisoner.

Later that day, Somerset sent soldiers with guns to take the Inveresk Slopes. These hills overlooked the Scottish position. During the night, Arran sent two more old-fashioned challenges to Somerset. One was for Somerset and Arran to fight each other to decide the battle. The other was for 20 champions from each side to fight. Somerset said no to both ideas.

The Battle Begins

On the morning of Saturday, September 10, Somerset moved his army forward. He wanted to place his cannons at Inveresk. In response, Arran moved his army across the Esk using the "Roman bridge." He advanced quickly to meet the English. Arran might have thought the English were trying to retreat to their ships. He knew his army had fewer good cannons. So, he tried to force a close fight before the English could use their artillery.

Arran's left side came under fire from English ships in the sea. Their advance meant their old gun positions could no longer protect them. This caused confusion and pushed them into Arran's main group in the center.

On the other side, Somerset sent his cavalry to slow down the Scots. The English cavalry were at a disadvantage. They had left their horses' armor at the camp. The Scottish pikemen pushed them back, causing many injuries. Lord Grey himself was wounded in the throat and mouth by a pike. At one point, Scottish pikemen surrounded the soldier carrying the King's Standard (flag). He was saved, and he held onto the flag, even though its pole broke.

The Scottish army was now stuck. They were under heavy fire from three sides: ships, land cannons, early firearms, and archers. They had no way to fight back. When they finally broke and ran, the English cavalry rejoined the fight. Many retreating Scots were killed or drowned. They tried to swim the fast-flowing Esk or cross the swamps.

What Others Said About the Battle

The ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire, François van der Delft, heard the news of the battle. He wrote to the Queen Dowager, Mary of Hungary, on September 19. He described the cavalry fight the day before the battle. He heard that during the main battle, Scottish horsemen got off their horses. They held their lances like pikes in a tight group.

Van der Delft was told that the Earl of Warwick tried to attack the Scots from behind. He used smoke from fires to hide his movements. When they attacked the Scottish rear, the Scots ran away. It seemed some Scots had already agreed to help the English leader, Somerset. The rest of the Scottish army then tried to escape.

Another letter about the battle was sent by John Hooper to a reformer in Switzerland. Hooper mentioned that the Scots had to leave their cannons. This was because of the archers led by the Earl of Warwick. He also said that when the Scots moved, the sun was in their eyes. He was told there were 15,000 Scottish deaths and 2,000 prisoners. These letters, written by people who were not in the battle, still help historians understand what happened.

What Happened After the Battle

Even though they lost badly, the Scottish government refused to give up. The baby Queen Mary was secretly sent to France. There, she was promised in marriage to the young French prince, Francis. Somerset took control of several Scottish castles and large parts of the Lowlands. But without peace, keeping these garrisons became a waste of money for England.

Scottish Cannons

The Scottish cannons were made ready at Edinburgh Castle. Extra gunners were hired. Many workers were used to move the guns. On September 2, carts were rented to take the guns and Scottish tents towards Musselburgh. There were horses and oxen to pull them.

After the battle, English officers found 30 Scottish cannons. They were left lying in different places. They found one large brass cannon, three smaller brass cannons, nine even smaller brass pieces, and 17 iron guns on carriages. Some of these guns later appeared in the English royal inventory at the Tower of London.

The Battle Site Today

The battle site is now in East Lothian. The battle likely happened in the fields southeast of Inveresk Church. This is just south of the main East Coast railway line. You can see the area from two good spots. Fa'side Castle was behind the English position. From there, you can get a good view of the battle area. The Scottish position is now covered by buildings.

The best way to see the Scottish position is from the golf course west of the River Esk. The Scottish center was a few yards west of the clubhouse. The Inveresk hill, which was important in the battle, is now built over. But you can walk down to the Esk and along its bank. This gives you an idea of part of the Scottish position. However, the town of Musselburgh now covers the left side of the Scottish line. The battlefield was added to the Inventory of Historic Battlefields in Scotland in 2011.

A stone monument marks the battle. It is southwest of Wallyford village. The stone has the St. Andrew's Cross, the English rose, and the Scottish thistle carved on it. It also has the battle's name and date.

In September 2017, the Scottish Battlefields Trust held the first big re-enactment of the battle. It took place at Newhailes House. These re-enactments are planned to happen every three years.

Who Was Lost in the Battle

Some injured soldiers were treated by Lockhart, a surgeon from Dunbar. Historian David H. Caldwell said that English reports claimed up to 15,000 Scots were killed. They also said 2,000 were captured. But the Earl of Huntly said about 6,000 Scots died, which is probably closer to the truth. Few of the Scottish prisoners were nobles or gentlemen. It was said they looked like common soldiers, so they were not recognized as important enough to ransom.

Caldwell also said that English losses were officially reported as only 200. But rumors and private letters from soldiers suggested that 500 or 600 English soldiers were killed.

William Patten listed some important people who died. The English he named were horsemen. They were forced onto Scottish pikes in a field east of the English position.

English Casualties

- Edward Shelley

- Sir Walter Hawksworth

- The Lord Fitzwalter's brother

- Sir John Clere's son

- Thomas Wodehouse

Scottish Casualties

- Malcolm, Lord Fleming

- David Forrester of Garden and Torwood

- Sir James Forrester of Corstorphine

- Robert, Master of Graham (killed by naval bombardment)

- Robert, Master of Erskine

- James, Master of Ogilvy

- The Master of Avondale

- The Master of Ruthven

- John Stewart, Master of Buchan

- The Master of Methven

- George Henderson of Fordell, and his oldest son William.

Many other Scottish casualties are known from old records:

- William Adamson of Craigcrook Castle.

- Andrew Agnew of Lochnaw Leswalt, Wigtownshire

- Gilbert Agnew, Wigtownshire

- James Allardice, who fell under the royal banner.

- Andrew Anstruther of that Ilk

- James Blair, Middle Auchindraine

- Thomas Brodie of Brodie

- Alan Cathcart, 3rd Lord Cathcart

- Thomas Corry of Kelwod

- William Cunninghame of Glengarnock Glengarnock Castle

- Gabriel Cunyngham, Laird of Craigends

- John Crawfurd of Auchinames Clan Crawford

- William Dishington of Ardross Clan Dishington

- Robert Douglas of Lochleven, father of William Douglas, 6th Earl of Morton.

- Thomas Dumbreck of that Ilk

- Archibald Dunbar of Baldoon, Kirkinner, Wigtownshire

- Alexander Dundas of Fingask

- Alexander Elphinstone, 2nd Lord Elphinstone

- Finla Mor, Findlay of Clan Farquharson, said to have carried the royal banner

- Sir James Gordon of Lochinvar

- John Gordon of Pitlurg

- David Hamilton of Broomhill, son-in-law of Robert, Lord Semple.

- Cuthbert Hamilton of Canir, brother-in-law of David Hamilton of Broomhill.

- Kentigern "Mungo" Huntar of Hunterston Castle

- George Home of Wedderburn.

- James Innes of Cromy.

- Alexander Irvine, Master of Drum

- William Johnston, younger of Caskieben

- John Kennedy of Kirkmichael

- Thomas Kennedy, Vicar of Penpont, a son of Gilbert Kennedy, 2nd Earl of Cassilis

- James Learmonth of Dairsie and Balcomie

- John Leckie of Leckie, Dumbartonshire.

- John, Master of Livingston, son of Alexander Livingston, 5th Lord Livingston

- John MacDowall of Garthland

- John MacDowall of Corswall, Kirkcolm, Wigtownshire

- Fergus McDouall of Freugh, Stoneykirk, Wigtownshire

- Richard Melville, father of Andrew Melville

- James Montfode of Montfode.

- Hugh Montgomerie, son of Earl of Eglinton

- Mungo Muir of Rowallan

- Robert Munro, 14th Baron of Foulis

- Bernard Mure of Park

- Alexander Napier of Merchiston

- Laurence Rankyne of Sheild Ochiltree

- William Rankyne of Sheild Ochiltree

- John Vans of Barnbarroch, Kirkinner, Wigtownshire

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Pinkie Cleugh para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Pinkie Cleugh para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |