Arquebus facts for kids

An arquebus (pronounced AR-kwuh-bus) was an early type of long gun. It first appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 1400s. A soldier who used an arquebus was called an arquebusier.

The word arquebus comes from the Dutch word Haakbus, meaning "hook gun." This name was used for many different firearms from the 1400s to the 1600s. Originally, it meant a hand cannon with a hook on its bottom. This hook helped steady the gun against walls or other objects when firing. These "hook guns" were first used as defensive weapons on German city walls in the early 1400s. Later, a shoulder stock, a priming pan, and a special firing system called a matchlock were added. This turned the arquebus into a handheld gun and the first firearm with a trigger.

Historians aren't sure exactly when the matchlock system first appeared. It might have been in the Ottoman Empire as early as 1465. In Europe, it appeared a little before 1475. A heavier version of the arquebus, later called a musket, was made to shoot through plate armor. This happened in Europe around 1521. Very heavy arquebuses used on war wagons were known as arquebus à croc. These could fire a lead ball weighing about 3.5 ounces.

A standard arquebus, called the caliver, was introduced in the late 1500s. The name "caliver" comes from the French word calibre, which means the gun's standard size. The caliver made it easier for soldiers to load bullets quickly. Before this, soldiers often had to change their bullets to fit their guns, or even make their own before a battle. The matchlock arquebus is seen as an early version of the flintlock musket.

Contents

What is an Arquebus?

The word arquebus comes from the Dutch word Haakbus (meaning "hook gun"). This term was used for many different firearms from the 1400s to the 1600s. At first, it described a hand cannon with a hook-like part on its underside. This hook helped steady the gun when firing it from battlements or other objects. The word arquebus was first definitely used in 1364. At that time, the lord of Milan, Bernabò Visconti, hired 70 archibuxoli. However, this probably meant a hand cannon then.

The arquebus has been called by many names over time. These include harquebus, hackbut, archibugio, haakbus, tüfenk, and matchlock.

Musket: A Bigger Arquebus

The musket was basically a larger arquebus. It was introduced around 1521. However, it became less popular by the mid-1500s because armor was used less often. But the name stuck around. Musket became a general term for smoothbore gunpowder weapons fired from the shoulder until the mid-1800s. Sometimes, musket and arquebus were even used to mean the same weapon. A commander in the 1560s once called muskets "double arquebuses." The matchlock firing system also became a common name for the arquebus once it was added. Later flintlock firearms were sometimes called fusils.

How the Arquebus Worked and Was Used

Before the matchlock system appeared around 1475, early handguns were fired differently. People held them against their chest or tucked them under one arm. With the other hand, they used a hot poker to light the gunpowder through a small hole. The matchlock changed this. It had two main parts: the match and the lock. The lock held a burning rope, about 2 to 3 feet long, soaked in saltpeter. This was the match. A trigger was connected to the lock lever. When squeezed, the trigger lowered the match into a small pan of priming powder. This powder would ignite, sending a flash through a touch hole. This flash then lit the main gunpowder inside the barrel, pushing the bullet out.

While matchlocks allowed soldiers to aim with both hands, they were tricky to use. To avoid accidentally setting off the gunpowder, the burning match had to be removed while loading the gun. Sometimes, the match would also go out, so both ends were kept lit. This was hard to handle, as both hands were needed to hold the match when removing it. The process was so complex that a 1607 training manual listed 28 steps just to fire and load the gun! In 1584, a Chinese general named Qi Jiguang created an 11-step song to help soldiers practice. Reloading an arquebus in the 1500s took anywhere from 20 seconds to a minute, even in perfect conditions.

The invention of volley fire made the arquebus much more useful for armies. This technique was used by the Ottomans, Chinese, Japanese, and Dutch. Volley fire turned soldiers with firearms into organized firing squads. Each row of soldiers would fire in turn, then reload in a systematic way. This method was first used with cannons by Chinese artillerists in 1388. But volley fire with matchlocks was first used in 1526 by the Ottoman Janissaries at the Battle of Mohács. It was later seen in China in the mid-1500s, thanks to Qi Jiguang, and in Japan in the late 1500s.

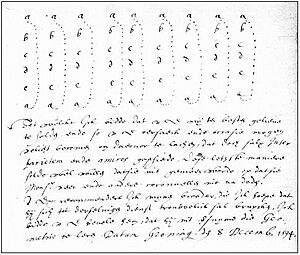

In Europe, William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg thought that matchlocks could fire without stopping. He suggested using the same Roman counter-march technique described by Aelianus Tacticus. In a letter from 1594, he wrote that as soon as the first row fired, they would march to the back to reload. The next row would then fire, and so on. This way, there would always be a row ready to shoot.

Once volley firing was developed, the arquebus became much faster and more effective. It changed from being a support weapon to the main weapon for most armies in the early modern period.

Another firing system, the wheellock, was used as early as 1505. But it was three times more expensive than a matchlock and often broke down. So, it was mainly used for special firearms and pistols. The snaphance flintlock was invented by the mid-1500s, and the "true" flintlock in the early 1600s. By this time, the general name for firearms had changed to musket. Flintlocks are usually not linked with arquebuses.

- Firing sequence

History of the Arquebus

Early Beginnings

The first known "arquebuses" appeared in Europe in 1411 and in the Ottoman Empire by 1425. These early guns were hand cannons with a lever to hold matches. However, they didn't have the full matchlock system we usually think of. The exact date the matchlock was added is debated. Some sources say the Ottoman Janissary corps used arquebuses (tüfek) as early as 1394 to 1465.

In Europe, a shoulder stock, possibly inspired by crossbows, was added to the arquebus around 1470. The matchlock system appeared a little before 1475. The matchlock arquebus was the first firearm with a trigger. It's also considered the first portable shoulder-fired gun.

Use by Different Empires

The Ottomans used arquebuses early on. During the Ottoman–Hungarian wars of 1443–1444, Ottoman defenders in Vidin had arquebuses. In the 1440s, Sultan Murad II's army had 400 arquebusiers. Arquebuses were also used in battle by the Ottomans at the second battle of Kosovo in 1448. The Ottomans also used "Wagon Fortresses," like the Hussites, placing arquebusiers in protective wagons.

In Europe, the arquebus was first used in large numbers during the reign of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (1458–1490). About one in four soldiers in his infantry used an arquebus. However, King Mathias preferred shielded men because the arquebus fired slowly. Even so, by the early 1500s, only about 10% of Western European infantry used firearms. The effectiveness of the arquebus became clear at the Battle of Cerignola in 1503. This was the first recorded battle where arquebuses played a key role in the outcome.

In Russia, a small arquebus called pishchal appeared in 1478. Russian arquebusiers, or pishchal'niki, were important parts of the army. Two thousand pishchal'niki were raised in 1545. They even used mounted troops, which was unusual at the time.

The Mamluks were initially against using gunpowder weapons. They criticized the Ottomans for using cannons and arquebuses. However, after being defeated by the Ottomans in 1514, the Mamluks were ordered to train with arquebuses. By the 1500s, the arquebus became a common infantry weapon because it was relatively cheap. An arquebus cost a little over one ducat, while a helmet, breastplate, and pike cost about three and a quarter ducats. Another big advantage was that soldiers could be trained to use an arquebus in just two weeks, while mastering a bow could take years.

Spread to Asia

The arquebus spread to India by 1500, Southeast Asia by 1540, and China between 1523 and 1548. In Japan, Portuguese traders accidentally introduced them in 1543 on the island of Tanegashima. By 1550, arquebuses, known as tanegashima or teppō, were being made in large numbers in Japan. Within ten years, over 300,000 tanegashima were reportedly made. Oda Nobunaga changed musket tactics in Japan. At the Battle of Nagashino in 1575, he may have used volley fire. Both Korean and Chinese sources note that Japanese gunners used volley fire during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598).

In Iran, Shah Ismail I began using arquebuses widely after being defeated by the Ottoman army in 1514. Less than 10 years later, he had an estimated 12,000 arquebusiers. However, firearms were not as widely adopted in Iran due to their reliance on light cavalry. Riding a horse and firing an arquebus was very difficult. Iran also used elephant-mounted arquebusiers, which gave them a better view and more mobility.

Southeast Asian powers started using arquebuses by 1540. The Ming dynasty in China considered Đại Việt (Vietnam) to have very advanced matchlocks in the 1500s and 1600s. These were said to be better than Ottoman, Japanese, and European firearms. Vietnamese matchlocks could reportedly pierce several layers of iron armor and kill multiple men with one shot.

The arquebus was introduced to the Ming dynasty in China in the early 1500s. It was used in small numbers to fight pirates by 1548. Around 10,000 muskets were ordered in 1558 to fight pirates. Qi Jiguang developed military formations for arquebus troops. These formations used counter-march volley fire. He also stressed practicing the reloading procedure to avoid accidents and keep a steady rate of fire. Qi Jiguang praised the gun in 1560, saying it could pierce armor and hit targets accurately, even the eye of a coin. He believed nothing was strong enough to defend against it.

European Arquebus Formations

In Europe, Maurice of Nassau developed the counter-march volley fire technique. In 1599, he equipped his entire army with new, standard weapons. At the Battle of Nieuwpoort in 1600, he used these new methods for the first time. The Dutch marched in a block formation, using volley fire to keep a steady stream of shots. This resulted in a big victory for the Dutch, with far fewer casualties than the Spanish. This battle was a major step in the development of early modern warfare, where firearms became much more important in Europe.

Eventually, "musket" became the main term for similar firearms starting in the 1550s. Arquebuses are most often linked with matchlocks.

Using Arquebuses with Other Weapons

The arquebus had many benefits but also some big weaknesses on the battlefield. Because of this, it was often used with other weapons to make up for its flaws. Qi Jiguang from China created systems where soldiers with traditional weapons stayed right behind the arquebusiers. This protected them if enemy infantry got too close. The English used pikemen to protect their arquebusiers. The Venetians often used archers to provide cover fire during the long reloading process. The Ottomans supported their arquebusiers with artillery fire or placed them in fortified wagons.

Arquebus vs. Bows

Some military writers in the 1500s debated whether an arquebus was better than a bow. An arquebus could shoot a bullet up to 1,000 meters or more, much farther than any archer could shoot. An arquebus shot was considered deadly up to 360 meters. The heavier Spanish musket was deadly up to 550 meters. During the Japanese Invasions of Korea, Korean officials said they were at a big disadvantage because Japanese arquebuses "could reach beyond several hundred paces."

Perhaps the most important advantage of the arquebus was its sheer power. A shot from a typical 16th-century arquebus had between 1300 to 1750 Joules of kinetic energy. A longbow arrow, in contrast, had about 80 Joules. Crossbows ranged from 100 to 200 Joules. This meant arquebuses could easily defeat armor that would stop arrows or bolts. They also caused much greater wounds.

Most skilled archers could shoot much faster than a matchlock arquebus, which took 30–60 seconds to reload. However, the arquebus fired faster than the most powerful crossbow. It also had a shorter learning curve than a longbow and was more powerful than both. The arquebus didn't need the user's physical strength to fire. This made it easier to find suitable recruits. It also meant an arquebusier lost less effectiveness due to tiredness or sickness. The arquebusier also had the advantage of scaring enemies (and horses) with its loud noise. Wind could affect archery accuracy, but had less effect on an arquebus. During a siege, it was also easier to fire an arquebus from loopholes than a bow and arrow.

An arquebus also had better penetrating power than a bow or crossbow. Some plate armors were bulletproof, but these were rare, heavy, and expensive. Most common armor had little protection against musket fire.

Training an effective arquebusier took much less time than training a skilled bowman. Most archers spent their whole lives training for accuracy. But with practice, an arquebusier could learn their job in months, not years. This made it much easier to equip an army quickly and increase the number of soldiers with small arms. This idea of less skilled, lightly armored units led to a big change in infantry warfare in the 1500s and 1600s.

An arquebusier could carry more ammunition and powder than a crossbowman or longbowman could carry bolts or arrows. Once the methods were developed, powder and shot were relatively easy to mass-produce. Making arrows, however, was a skilled craft.

However, the arquebus was more sensitive to rain, wind, and humid weather. At the Battle of Villalar, rebel troops lost partly because many of their arquebuses became useless in a rainstorm. Gunpowder also spoiled faster than a bolt or arrow, especially if not stored properly. Finding and reusing arrows or bolts was easier than doing the same with arquebus bullets. A bullet had to fit a barrel very precisely. This meant arquebuses needed more standardization, making it harder to resupply by looting fallen soldiers. Making gunpowder was also much more dangerous than making arrows or bolts.

An arquebus was also more dangerous to its user. The arquebusier carried a lot of gunpowder and had a lit match. In the confusion of battle, arquebusiers could be a danger to themselves. Early arquebuses often had a strong recoil. They took a long time to load, making soldiers vulnerable while reloading unless using the 'continuous fire' tactic. Guns could also overheat and explode during repeated firing, which was dangerous.

Also, black-powder weapons produced a lot of smoke. This made it hard to see the enemy after a few shots, unless there was enough wind to clear the smoke quickly. (But this smoke cloud also made it hard for archers to target the soldiers using firearms.) Before the wheellock, the need for a lit match made stealth almost impossible, especially at night. Even if hidden, the smoke from one arquebus shot would show where it came from. While a soldier could kill silently with a bow or crossbow, this was impossible with an explosion-driven weapon like the arquebus. The loud noise of arquebuses could also make it hard to hear shouted commands. Over time, the weapon could cause permanent hearing loss.

See Also

- Blunderbuss

- Tanegashima

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |