Ismail I facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ismail Iاسماعیل یکم |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||

| Shah of Iran | |||||||||

| Reign | 22 December 1501 – 23 May 1524 | ||||||||

| Successor | Tahmasp I | ||||||||

| Viziers |

See list

Amir Zakariya

Mahmud Jan Daylami Najm-e Sani Abd al-Baqi Yazdi Mirza Shah Hossein Jalal al-Din Mohammad Tabrizi |

||||||||

| Born | 17 July 1487 Ardabil, Aq Qoyunlu |

||||||||

| Died | 23 May 1524 (aged 36) Near Tabriz, Safavid Iran |

||||||||

| Burial | Sheikh Safi Shrine Ensemble, Ardabil, Iran | ||||||||

| Spouse | Tajlu Khanum Behruzeh Khanum |

||||||||

| Issue Among others |

Tahmasp I Sam Mirza Alqas Mirza Bahram Mirza Parikhan Khanum Mahinbanu Khanum |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Dynasty | Safavid | ||||||||

| Father | Shaykh Haydar | ||||||||

| Mother | Halima Begum | ||||||||

| Religion | Twelver Shia Islam | ||||||||

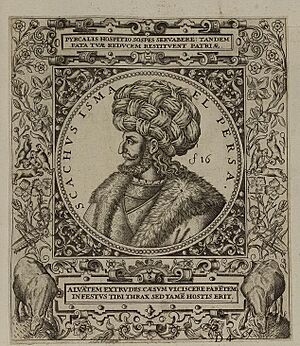

Ismail I (Persian: اسماعیل, romanized: Esmāʿīl; born July 17, 1487 – died May 23, 1524), also known as Shah Ismail, was the person who started the Safavid dynasty in Iran. He ruled as its King of Kings (Shahanshah) from 1501 to 1524. His time as ruler is often seen as the start of modern Iranian history. It was also part of the "gunpowder empires," which were powerful states that used new weapons like cannons and muskets.

Ismail I's rule was very important for the history of Iran. Before he became ruler in 1501, Iran had not been a united country under Iranian rule for a long time. It had been controlled by different groups like Arab caliphs, Turkic sultans, and Mongol khans.

The Safavid dynasty that Ismail I founded would rule for over 200 years. It became one of the greatest Iranian empires. At its strongest, it was one of the most powerful empires of its time. It controlled all of present-day Iran, Azerbaijan Republic, Armenia, most of Georgia, parts of the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan. It also ruled parts of modern-day Syria, Turkey, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. The Safavid Empire also helped bring back the Iranian identity in many areas. It made Iran a strong economic center between the East and West. It also set up a good government system and supported art and architecture.

One of Ismail's first big decisions was to make Twelver Shia Islam the official religion of his new Persian Empire. This was a major turning point in the history of Islam. It had big effects on Iran's future. This change caused some disagreements in the Middle East. It also helped separate the growing Safavid Empire from its Sunni neighbors, like the Ottoman Empire to the west and the Uzbeks to the east.

Ismail I was also a talented poet. He wrote under the name Khataʾi. He wrote many poems in the Azerbaijani language, which helped it grow as a literary language. He also wrote some poems in Persian.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Ismail I was born on July 17, 1487, in Ardabil. His father, Shaykh Haydar, was a leader of the Safavid order, a Sufi group. His family was directly related to the founder of this order, Safi-ad-din Ardabili. Ismail was the last leader of this religious order before it became a ruling family.

His mother, Martha, was also known as Alemshah Halime Begum. She was the daughter of Uzun Hasan, who ruled the Aq Qoyunlu dynasty. Her mother was Theodora Megale Komnene, a Greek princess. She had married Uzun Hassan to protect her empire from the Ottoman Turks. Ismail was related to several royal families, including emperors of Trebizond and kings of Georgia.

Ismail grew up speaking two languages: Persian and Azerbaijani. His family background was a mix of different groups, including Georgians, Greeks, Kurds, and Turkomans. Most experts agree that his empire was an Iranian one.

The Safavid order was founded by Safi al-Din. Some people believed that Sheikh Safi was a direct descendant of Ali, an important figure in Islam. Ismail also said he was the Mahdi, a spiritual leader, and a new form of Ali.

Rise to Power

In 1488, Ismail's father was killed in a battle against the forces of the Shirvanshah Farrukh Yassar and the Aq Qoyunlu. The Aq Qoyunlu was a group of Turkic tribes that controlled most of Iran. In 1494, the Aq Qoyunlu captured Ardabil and killed Ismail's older brother. This forced 7-year-old Ismail to hide in Gilan. There, he was taught by scholars under the ruler Soltan-Ali Mirza.

When Ismail was 12, he came out of hiding. He returned to what is now Iranian Azerbaijan with his followers. Ismail became powerful thanks to the Turkoman tribes from Anatolia and Azerbaijan. These tribes were a very important part of the Qizilbash movement, which supported him.

Ruling as Shah

Conquering Lands

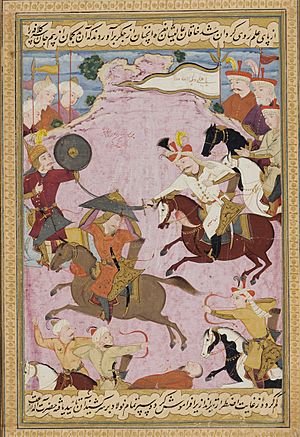

In the summer of 1500, Ismail gathered about 7,000 Qizilbash soldiers. They crossed the Kura River in December 1500 and marched towards the Shirvanshah's state. They defeated the Shirvanshah's forces and took over Baku. This meant Shirvan and its surrounding areas were now under Ismail's control.

This success worried Alvand, the ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu. He came north from Tabriz to fight Ismail's forces. They met at the battle of Sharur. Ismail's army won, even though they were outnumbered. Before attacking Shirvan, Ismail had promised the Georgian kings that he would stop their tribute payments if they helped him against the Ottomans. After taking Tabriz and Nakhchivan, Ismail did not keep his promise. Instead, he made the Georgian kingdoms his vassals, meaning they had to obey him.

In July 1501, Ismail became the Shah of Iran and made Tabriz his capital. He appointed his former teacher, Husayn Beg Shamlu, as the empire's vakil (a high official) and the leader of the Qizilbash army. He also made Amir Zakariya, an Iranian official, his vizier (another high-ranking minister). After becoming Shah, Ismail declared that Twelver Shi'ism was the official and required religion of Iran. He made sure this new rule was followed strictly.

A poet and official from that time, Qāsim Beg Ḥayātī Tabrīzī, wrote that Shah Ismail became ruler in Tabriz on December 22, 1501. This was right after the battle of Sharur.

After defeating another Aq Qoyunlu army in 1502, Ismail took the title "Shah of Iran." In the same year, he gained control of Erzincan and Erzurum. A year later, in 1503, he conquered Eraq-e Ajam and Fars. In 1504, he took Mazandaran, Gorgan, and Yazd. In 1507, he conquered Diyarbakır. During this time, Ismail started to trust Iranians more than the Qizilbash. The Qizilbash had helped him a lot, but they had too much power.

A year later, Ismail made the rulers of Khuzestan, Lorestan, and Kurdistan his vassals. In the same year, Ismail and Husayn Beg Shamlu captured Baghdad, ending the Aq Qoyunlu rule. Ismail then began to remove Sunni religious sites in Baghdad.

By 1510, he had conquered all of Iran, southern Dagestan, Mesopotamia, Armenia, Khorasan, and Eastern Anatolia. He also made the Georgian kingdoms his vassals. In the same year, Husayn Beg Shamlu lost his position as army chief. Ismail appointed Mohammad Beg Ustajlu, a man from a humble background, instead.

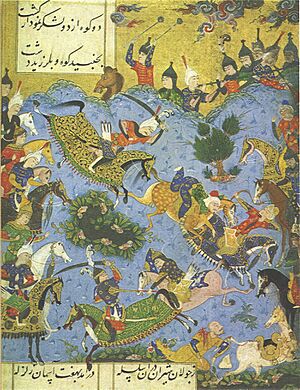

Ismail I then moved against the Uzbeks. In a battle near the city of Merv, about 17,000 Qizilbash warriors surprised and defeated an Uzbek army of 28,000. The Uzbek ruler, Muhammad Shaybani, was killed trying to escape.

Conflict with the Ottomans

Ismail's efforts to get support from Turkoman tribes in Eastern Anatolia caused problems with the neighboring Ottoman Empire. These tribes were Ottoman subjects. The Ottomans, who followed Sunni Islam, were worried about the spread of Shia ideas in their lands. They also feared that the Safavids might take over large areas in Asia Minor. By the early 1510s, Ismail's fast expansion had moved the Safavid border further west.

In 1511, there was a large rebellion in southern Anatolia by a Qizilbash tribe. An Ottoman army sent to stop it was defeated. A major attack into Eastern Anatolia by Safavid fighters happened when Sultan Selim I became the Ottoman ruler in 1512. This led Selim to decide to invade Safavid Iran two years later. Selim and Ismail had exchanged angry letters before the attack.

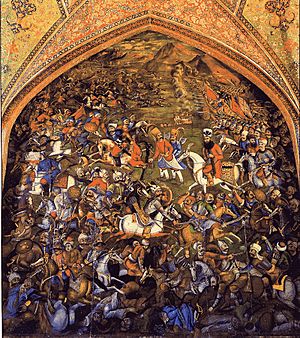

Selim I eventually defeated Ismail at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. Ismail's army was faster and his soldiers were well-prepared. However, the Ottomans won because they had a modern army with artillery, gunpowder, and muskets. Ismail was hurt and almost captured in the battle. Selim entered the Iranian capital of Tabriz in triumph. But he did not stay long. His troops worried about a counterattack and being trapped. This forced the Ottomans to leave early. This allowed Ismail to recover. The Ottomans did take Eastern Anatolia and parts of Mesopotamia, and briefly northwestern Iran.

Later Years and Death

After the Battle of Chaldiran, Shah Ismail felt very sad and depressed. He lost his feeling of being unbeatable. He stayed in his palace and never led a military campaign again. He also stopped being actively involved in running the state. He left these duties to his vizier, Mirza Shah Husayn. Mirza Shah Husayn gained a lot of power over Ismail. Mirza Shah Husayn was killed in 1523 by some Qizilbash officers. After this, Ismail appointed Jalal al-Din Mohammad Tabrizi as his new vizier.

Ismail died on May 23, 1524, when he was 36 years old. He was buried in Ardabil. His son, Tahmasp I, became the next ruler.

The defeat at Chaldiran also affected Ismail deeply. His relationship with his Qizilbash followers changed. The rivalries between the Qizilbash tribes, which had stopped before the battle, started again strongly after Ismail's death. This led to ten years of civil war until Shah Tahmasp took full control of the state.

During Ismail's rule, especially in the late 1510s, there were early talks about an alliance between the Safavids and European powers. Charles V and Ludwig II of Hungary talked about working together against their common enemy, the Ottoman Turks.

Royal Ideas

From a young age, Ismail knew a lot about Iranian culture and history. He even had a copy of the famous Persian epic, Shahnameh (Book of Kings), with many illustrations. Because he loved Iranian legends, Ismail named three of his four sons after legendary kings and heroes from the Shahnameh. His oldest son was named Tahmasp, after an ancient king. His third son, Sam, was named after a hero. His youngest son, Bahram, was named after a Sasanian king known for his romantic life.

Ismail's knowledge of Persian stories like the Shahnameh helped him present himself as a true Iranian king. He wanted to be seen as a great Iranian ruler, like the legendary king Kaykhosrow. This king defeated the Turanian king Afrasiyab, who was Iran's enemy. In Iran, Turan was often linked to the land of the Turks, especially the Uzbeks. After Ismail defeated the Uzbeks, his victory was shown as a win over the mythical Turanians.

The Safavids also used Turkic and Mongol ideas in their rule. They gave important positions to Turkic leaders and used Turkic tribes in their wars. They also used Turkic-Mongolian titles like khan. Over time, the Safavids included more cultural ideas. Ismail and the rulers after him brought in Kurds, Arabs, Georgians, Circassians, and Armenians into their government.

Ismail's Poetry

Ismail is also known for his poetry. He used the pen-name Khaṭā'ī, which means "the wrongful." He wrote in the Azerbaijani language, which is a Turkic language similar to Turkish. He also wrote some poems in Persian. He is an important person in the history of Azerbaijani literature. He wrote about 1400 verses in Azerbaijani, which he chose for political reasons. Only about 50 verses of his Persian poetry have survived.

Experts say that "Ismail was a skilled poet who used common themes and images in his poems easily and with some new ideas." He was also greatly influenced by Persian literary tradition, especially the Shahnameh by Ferdowsi. This is probably why he named all his sons after characters from the Shahnameh.

Most of his poems are about love, especially a spiritual kind of love. But he also wrote poems that promoted Shia beliefs and Safavid politics. His other important works include the Nasihatnāme, a book of advice in Azerbaijani, and the unfinished Dahnāme, which praises the good things about love.

Along with the poet Imadaddin Nasimi, Khatā'ī is seen as one of the first to use a simpler Azerbaijani language in poetry. This made his poems appeal to more people. His work is very popular in Azerbaijan and among the Bektashis in Turkey. Many Alevi and Bektashi poems are believed to be his. His religious writings had a big impact, helping to change Persia from Sunni to Shia Islam in the long run.

There is a story that Khatā'ī sent a poem in Turkish to the Ottoman Sultan Selim I before they went to war in 1514. The Ottoman Sultan replied in Persian to show his disapproval.

Appearance

People who knew Ismail described him as looking like a king. He was polite and seemed young. He had a fair complexion and red hair. His appearance was different from other olive-skinned Persians. His family background and religious beliefs made people expect great things from him. This was because of many legends that were popular during that time in Western Asia.

Legacy

Ismail's greatest achievement was creating an empire that lasted over 200 years. As historian Alexander Mikaberidze says, "The Safavid dynasty would rule for two more centuries and create the foundation for the modern-nation state of Iran." Even after the Safavids fell in 1736, their culture and politics continued to influence Iran. This influence can still be seen in the modern Islamic Republic of Iran and the neighboring Azerbaijan Republic. In these places, Shi'a Islam is still the main religion, just as it was during the Safavid era.

See also

In Spanish: Ismaíl I para niños

In Spanish: Ismaíl I para niños

- Safavid dynasty family tree

- List of Turkic-languages poets

- Safavid conversion of Iran from Sunnism to Shiism

- Seven Great Poets

Images for kids

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |