Tahmasp I facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tahmasp I |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of kings of Persia | |||||

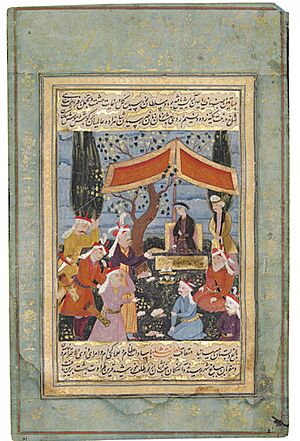

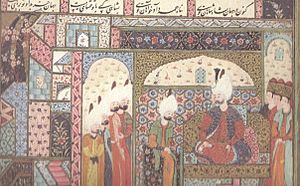

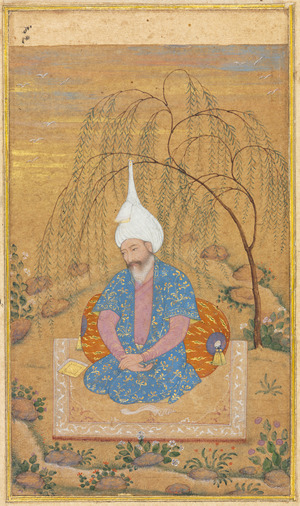

Shah Tahmasp I in the mountains (detail), by Farrukh Beg

|

|||||

| Shah of Iran | |||||

| Reign | 23 May 1524 – 25 May 1576 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 June 1524 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ismail I | ||||

| Successor | Ismail II | ||||

| Regent |

See list

Div Sultan Rumlu Kopek Sultan Chuha Sultan Hossein Khan |

||||

| Born | 22 February 1514 Shahabad, Isfahan, Safavid Iran |

||||

| Died | 25 May 1576 (aged 62) Qazvin, Safavid Iran |

||||

| Spouse | Many, among them: Sultanum Begum Sultan-Agha Khanum |

||||

| Issue | See below | ||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Safavid | ||||

| Father | Ismail I | ||||

| Mother | Tajlu Khanum | ||||

| Religion | Twelver Shia Islam | ||||

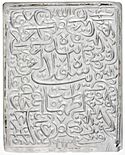

| Seal |  |

||||

Tahmasp I (Persian: طهماسب یکم, romanized: Ṭahmāsb or تهماسب یکم Tahmâsb; 22 February 1514 – 14 May 1576) was the second ruler, or shah, of the Safavid Empire in Iran. He ruled for a very long time, from 1524 until he died in 1576. He was the oldest son of Shah Ismail I and his main wife, Tajlu Khanum.

Tahmasp became shah after his father passed away on May 23, 1524. The first years of his rule were difficult due to civil wars among the Qizilbash leaders. But by 1532, he took full control and became an absolute ruler. He then faced a long war with the Ottoman Empire, which happened in three parts. The Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, tried to put his own chosen rulers on the Safavid throne. The war ended in 1555 with the Peace of Amasya. This agreement gave the Ottomans control over Iraq, much of Kurdistan, and western Georgia. Tahmasp also had fights with the Uzbeks from Bukhara over the region of Khorasan. The Uzbeks often attacked Herat. In 1528, when he was only fourteen, Tahmasp used artillery to defeat the Uzbeks in the Battle of Jam.

Tahmasp loved the arts and was a skilled painter himself. He created a special royal art house for painters, calligraphers, and poets. Later in his rule, he became less fond of poets, sending many away to the Mughal court in India. Tahmasp was known for being very religious and a strong supporter of the Shia branch of Islam. He gave many special rights to religious leaders and let them help with legal and government matters. In 1544, he asked the Mughal emperor Humayun, who was running away from his enemies, to become Shia in exchange for military help to get his throne back in India. Even so, Tahmasp also made alliances with Christian countries like the Republic of Venice and the Habsburg monarchy, who were also enemies of the Ottoman Empire.

There was a disagreement about who would rule after Tahmasp died. When he passed away, a civil war started, and most of the royal family members were killed. Tahmasp ruled for almost fifty-two years, which was the longest of any Safavid ruler. People in the West at the time were critical of him, but modern historians see him as a brave and capable leader who kept and even expanded his father's empire. His rule changed the Safavid government's ideas. He stopped the Qizilbash tribes from worshipping his father as the Messiah. Instead, he presented himself as a religious and traditional Shia king. He started a long process, continued by later rulers, to reduce the Qizilbash's power in Safavid politics. He replaced them with a new group, called the 'third force,' made up of Islamized Georgians and Armenians.

Contents

What Does the Name Tahmasp Mean?

"Tahmasp" (Persian: طهماسب, romanized: Ṭahmāsb) is a New Persian name. It comes from an old Iranian word *ta(x)ma-aspa, which means "having brave horses." This name is one of the few from the famous epic poem Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) that was used by an Islamic dynasty in Iran. In the Shahnameh, Tahmasp is the father of Zaav, a mythical Persian king.

How Tahmasp Became Shah

Tahmasp was the second shah of the Safavid dynasty. This family came from Kurdish origins and were leaders of a Sufi group called the Safavid order. Their main center was in Ardabil, a city in northwestern Iran. The first leader of this group, Safi-ad-din Ardabili (who died in 1334), married the daughter of Zahed Gilani. Two of Safi-ad-Din's family members, Shaykh Junayd (died 1460) and his son, Shaykh Haydar (died 1488), made the group more like a military force. They tried to expand their lands but were not successful.

Tahmasp's father, Ismail I (ruled 1501–1524), took over the Safavid order from his grandfather, Shaykh Haydar. He became the shah of Iran in 1501. At that time, Iran was in a civil war after the Timurid Empire fell apart. Ismail conquered lands from the Aq Qoyunlu tribal group, the Uzbek Shaybanid dynasty in eastern Iran, and many city-states by 1512. Ismail's empire included all of modern Iran, plus control over Georgia, Armenia, Daghestan, and Shirvan in the west, and Herat in the east. Unlike his Sufi ancestors, Ismail believed in Twelver Shia Islam and made it the official religion of his empire. He made the Sunni population convert to Shia Islam. He closed Sunni Sufi groups, took their property, and gave Sunni religious leaders a choice: convert, die, or leave. This created a gap in power, which allowed Shia religious leaders to become powerful landowners.

Ismail made the Qizilbash Turkoman tribes a key part of the Safavid government. They were the "men of the sword" who helped him gain power. These "men of the sword" often argued with the "men of the pen," who were mostly Persian scholars and controlled the government paperwork. Ismail created a new title, vakil-e nafs-e nafs-e homayoun (deputy to the king), to try and solve these arguments. The vakil had more power than both the military commander and the head of the government. This person was Ismail's representative in the royal court. However, this new title did not stop the fights between the Qizilbash leaders and Persian officials. These fights reached a peak in the Battle of Ghazdewan between the Safavids and the Uzbeks. During this battle, Ismail's vakil, the Persian Najm-e Sani, led the army. The Uzbeks won because many Qizilbash soldiers left the battle.

The Uzbeks from Bukhara were a constant problem on Iran's eastern borders. The Safavids and the Shaybanids became powerful around the same time in the early 1500s. By 1503, when Ismail I had taken control of large parts of the Iranian plateau, Muhammad Shaybani, the Khan of Bukhara (ruled 1500–1510), had conquered Khwarazm and Khorasan. Ismail defeated and killed Muhammad Shaybani in the Battle of Marv in 1510, bringing Khorasan back under Iranian control. However, Khwarazm and the Persian cities in Transoxiana remained with the Uzbeks. After this, control of Khorasan became the main reason for conflict between the Safavids and Shaybanids.

In 1514, Ismail's reputation was hurt when he lost the Battle of Chaldiran against the Ottoman Empire. Before this war, Ismail claimed to be a new version of Ali or Husayn. This belief weakened after Chaldiran, and Ismail lost the strong religious connection he had with the Qizilbash tribes, who had previously thought he was unbeatable. This affected Ismail deeply. He became sad and never led an army again. This allowed the Qizilbash tribes to gain power, which greatly influenced Tahmasp's early rule.

Tahmasp's Childhood

Abu'l-Fath Tahmasp Mirza was born on February 22, 1514, in Shahabad, a village near Isfahan. He was the oldest son of Ismail I and his main wife, Tajlu Khanum. Stories say that on the night Tahmasp was born, a big storm with wind, rain, and lightning happened. Tajlu Khanum, feeling her labor pains, suggested that the royal group stop in a village. So, they went to Shahabad. The village leader was Sunni and would not let Tajlu Khanum into his house. But a Shia person in the village welcomed her into his simple home. By then, Tajlu Begum had fainted from the pain, and soon after entering the house, she gave birth to a son. When Ismail heard the news, he was very happy. But he waited to see his son until his astrologers told him it was a lucky day. When the right time came, the young boy was shown to Ismail. Astrologers predicted his future would involve both war and peace, and that he would have many sons. Ismail named the boy Tahmasp because Ali, the first Imam, told him to in a dream.

In 1516, when Tahmasp Mirza was two years old, his father Ismail ordered that the province of Khorasan become his land. This was done to copy the Timurid dynasty, who used to appoint their oldest son to govern important provinces like Khorasan. The main city of this province, Herat, became the place where Safavid princes were raised, trained, and educated throughout the 1500s. In 1517, Ismail appointed Diyarbakr governor Amir Soltan Mawsillu as Tahmasp's tutor and governor of Balkh, a city in Khorasan. He replaced the previous governors of Khorasan, who had not joined his army during the Battle of Chaldiran. Placing Tahmasp in Herat was a way to reduce the growing power of the Shamlu tribe, who had a lot of influence in the Safavid court. Ismail also appointed Amir Ghiyath al-Din Mohammad, an important person in Herat, as Tahmasp's religious teacher.

A fight for control of Herat started between the two tutors. Amir Soltan arrested Ghiyath al-Din and killed him the next day. But Amir Soltan was removed from his position in 1521 by a sudden attack from the Uzbeks. They crossed the Amu Darya river and took parts of the city. Ismail then appointed Div Sultan Rumlu as Tahmasp's tutor, and the governorship was given to his younger son, Sam Mirza Safavi. During his years in Herat, Tahmasp learned to love writing and painting. He became a skilled painter and even dedicated a work to his brother, Bahram Mirza. The painting was a funny picture of Safavid court members, with music and singing.

In the spring of 1524, Ismail became sick on a hunting trip to Georgia. He got better in Ardabil on his way back to the capital. But he soon got a high fever, which led to his death on May 23, 1524, in Tabriz.

Early Rule and Challenges

The ten-year-old Tahmasp became shah after his father's death. He was guided by Div Sultan Rumlu, his tutor, who was the real ruler of the empire. Other Turkoman tribes of the Qizilbash, especially the Ostajlu and Takkalu, did not like that a member of the Rumlu tribe was in charge. Kopek Sultan, the governor of Tabriz and leader of the Ostajlu, along with Chuha Sultan, leader of the Takkalu tribe, were Div Sultan Rumlu's strongest opponents. The Takkalu were powerful in Isfahan and Hamadan, and the Ostajlu controlled Khorasan and the Safavid capital, Tabriz. Rumlu suggested that the three leaders share power, and they agreed. But this shared rule did not last because everyone was unhappy with their share of power. In the spring of 1526, battles between these tribes in northwest Iran spread to Khorasan and became a civil war. The Ostajlu group was quickly defeated, and their leader, Kopek Sultan, was killed by Chuha Sultan's order. During the civil war, Uzbek raiders temporarily took Tus and Astarabad. Div Sultan Rumlu was blamed for these attacks and was killed. Tahmasp himself carried out his execution.

At the young king's request, Chuha Sultan, the only remaining leader of the three, became the real ruler from 1527 to 1530. Chuha tried to take Herat from the Shamlu tribe, which led to a fight between the two tribes. In early 1530, the Herat governor, Hossein Khan Shamlu, and his men killed Chuha and executed every Takkalu in the shah's group. This made the Takkalu tribe rebel. A few days later, they attacked the shah's group in Hamadan to get revenge. One of the tribesmen tried to kidnap the young Tahmasp, who had him killed. Then Tahmasp ordered a general killing of the Takkalu tribe. Many were killed, and many fled to Baghdad. Eventually, the remaining Takkalu managed to escape to the Ottoman Empire. In old writings, the fall of Chuha Sultan and the killing of his tribe is called "the Takkalu pestilence." Hossein Khan Shamlu then took Chuha Sultan's place with the agreement of the Qizilbash leaders.

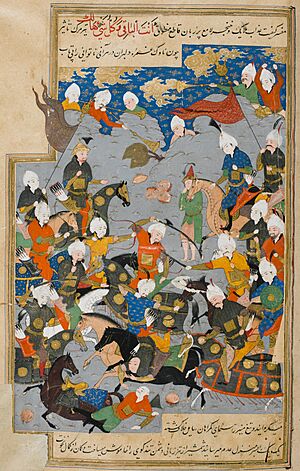

While the civil war was happening among the Qizilbash, the Uzbeks, led by Ubayd Allah Khan, conquered the border areas. In 1528, Ubayd took back Astarabad and Tus and surrounded Herat. Fourteen-year-old Tahmasp led the army and defeated the Uzbeks, showing his bravery at the Battle of Jam. The Safavids won because of several reasons, including their use of artillery, which they had learned from the Ottomans. The governor of Herat and Tahmasp's guide, Hossein Khan Shamlu, fought well in the battle and earned the shah's respect. However, this victory did not stop the Uzbek threat or the chaos inside the empire. Tahmasp had to return west to stop a rebellion in Baghdad. That year, the Uzbeks captured Herat, but they allowed Sam Mirza to return to Tabriz. Their control did not last long, and Tahmasp drove them out in the summer of 1530. He appointed his brother, Bahram Mirza, as governor of Khorasan and Ghazi Khan Takkalu as Bahram's tutor.

By this time, Tahmasp was seventeen and no longer needed a guide. Hossein Khan Shamlu tried to keep his power by becoming the guardian of Tahmasp's newborn son, Mohammad Mirza. Hossein Khan constantly weakened the shah's power and made Tahmasp angry many times. His confidence, combined with rumors that he planned to remove Tahmasp and put his brother, Sam Mirza, on the throne, finally led Tahmasp to get rid of the powerful Shamlu leader. So, Hossein Khan was overthrown and executed in 1533. His fall was a turning point for Tahmasp. He now understood that each Turkoman leader would favor his own tribe. He reduced the power of the Qizilbash and gave more power to the "men of the pen" (the government officials), ending the period of regency.

Tahmasp's Reign

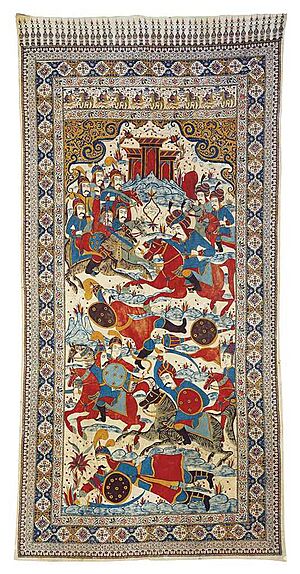

Wars with the Ottoman Empire

Suleiman the Magnificent (ruled 1520–1566), the sultan of the Ottoman Empire, might have seen a strong Safavid empire as a threat to his plans in the west. However, during the first ten years of Tahmasp's rule, Suleiman was busy fighting the Habsburgs and trying to capture Vienna, which he failed to do in 1529. In 1532, while the Ottomans were fighting in Hungary, Suleiman sent Olama Beg Takkalu with 50,000 soldiers to Iran. Olama Beg was one of many Takkalu members who had fled to the Ottoman Empire after Chuha's death. The Ottomans took Tabriz and Kurdistan and tried to get support from Gilan province. Tahmasp drove the Ottomans out, but news of another Uzbek invasion stopped him from fully defeating them. Suleiman sent his main minister, Ibrahim Pasha, to take Tabriz in July 1534 and joined him two months later. Suleiman peacefully conquered Baghdad and Shia cities like Najaf. While the Ottomans were marching, Tahmasp was in Balkh, fighting against the Uzbeks.

The first Ottoman invasion caused the biggest crisis of Tahmasp's rule. It is hard to know exactly what happened during this time. At some point, a person from the Shamlu tribe tried to poison Tahmasp but failed. The Shamlu then rebelled against the shah, who had recently taken power from Hossein Khan. To remove Tahmasp from the throne, they chose one of his younger brothers, Sam Mirza (who had a Shamlu guardian), as their choice for ruler. The rebels then contacted Suleiman and asked for his help to make Sam Mirza king. Sam Mirza promised to support the Ottomans. Suleiman recognized him as the ruler of Iran, which caused panic in Tahmasp's court. Tahmasp took back the captured land when Suleiman went to Mesopotamia. Suleiman then led another campaign against him. Tahmasp attacked the Ottoman army from behind, and Suleiman was forced to retreat to Istanbul by the end of 1535, losing all his gains except Baghdad. After fighting the Ottomans, Tahmasp quickly went to Khorasan to defeat his brother. Sam Mirza gave up and asked Tahmasp for mercy. The shah accepted his brother's pleas and sent him away to Qazvin but executed many of his advisors, including his Shamlu guardian.

Relations with the Ottomans remained unfriendly until the rebellion of Alqas Mirza, another of Tahmasp's younger brothers. Alqas had led the Safavid army during the 1534–35 Ottoman invasion and was governor of Shirvan. He led an unsuccessful revolt against Tahmasp, who conquered Derbant in the spring of 1547 and appointed his son Ismail as governor. Alqas fled to Crimea with his remaining forces and found safety with Suleiman. He promised to bring back Sunni Islam in Iran and encouraged the Sultan to lead another campaign against Tahmasp. The new invasion aimed to quickly capture Tabriz in July 1548. However, it soon became clear that Alqas Mirza's claims of support from all the Qizilbash leaders were false. The long campaign focused on stealing and destroying, plundering Hamadan, Qom, and Kashan before being stopped at Isfahan. Tahmasp did not fight the tired Ottoman army but destroyed the entire region from Tabriz to the border. The Ottomans could not permanently hold the captured lands because they soon ran out of supplies.

Eventually, Alqas Mirza was captured in battle and put in a fortress, where he died. Suleiman ended his campaign, and by the fall of 1549, the remaining Ottoman forces retreated. The Ottoman sultan launched his last campaign against the Safavids in May 1554. This was after Ismail Mirza (Tahmasp's son) invaded eastern Anatolia and defeated Erzerum governor Iskandar Pasha. Suleiman marched from Diyarbakr towards Armenian Karabakh and took back the lost lands. Tahmasp divided his army into four groups and sent each in a different direction. This showed that the Safavid army had grown much larger than in previous wars. With Tahmasp's Safavids having the advantage, Suleiman had to retreat. The Ottomans negotiated the Peace of Amasya. In this treaty, Tahmasp recognized Ottoman control in Mesopotamia and much of Kurdistan. Also, to show respect to Sunni Islam and Sunnis, he banned the celebration of Omar Koshan (a festival remembering the killing of the second caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab) and showing hatred towards the Rashidun caliphs, who are important to Sunni Muslims. The Ottomans allowed Iranian pilgrims to travel freely to Mecca, Medina, Karbala, and Najaf. Through this treaty, Iran had time to strengthen its army and resources, and its western provinces could recover from the war. This peace also set the border between the Ottoman and Safavid empires in the northwest without giving up large areas of Safavid land. These terms, which were good for the Safavids, showed how frustrated Suleiman the Magnificent was that he could not defeat the Safavids more completely.

Campaigns in Georgia

Tahmasp was interested in the Caucasus, especially Georgia, for two main reasons. First, he wanted to reduce the power of the Ostajlu tribe, who still held lands in southern Georgia and Armenia after the 1526 civil war. Second, he wanted to gain wealth, just like his father did. Since most Georgians were Christian, he used the idea of a holy war (Jihad) to justify his invasions. Between 1540 and 1553, Tahmasp led four campaigns against the Georgian kingdoms. In the first campaign, the Safavid army looted Tbilisi, including its churches, and took the wives and children of noble families as prisoners. Tahmasp also forced the governor of Tbilisi, Golbad, to convert to Islam. The King of Kartli, Luarsab I (ruled 1527/1534–1556/1558), managed to escape and hide during Tahmasp's raids. During his second invasion, which was supposedly to make Georgian territory stable, he looted farms and brought Levan of Kakheti (ruled 1518/1520–1574) under his control. One year before the Peace of Amasya in 1554, Tahmasp led his last military campaign into the Caucasus. Throughout his campaigns, he took many prisoners. This time, he brought 30,000 Georgians to Iran. Luarsab's mother, Nestan Darejan, was captured during these campaigns but took her own life after being imprisoned. The descendants of these prisoners formed a "third force" in the Safavid government and administration, alongside the Turkomans and Persians. This new group became a major rival to the other two in the later years of the Safavid Empire. Although this "third force" gained power two generations later during the rule of Tahmasp's grandson, Abbas the Great (ruled 1588–1629), it started to join Tahmasp's army during the second quarter of his rule as slave warriors (gholams) and royal bodyguards (qorchis). They became more influential at the height of the Safavid empire.

In 1555, after the Peace of Amasya, eastern Georgia remained under Iranian control, and western Georgia was ruled by the Turks. Tahmasp never appeared on the Caucasus border again after the treaty. Instead, the Governor of Georgia, Shahverdi Sultan, represented Safavid power north of the Aras River. Tahmasp tried to show his power by bringing in Iranian political and social systems and placing converts to Islam on the thrones of Kartli and Kakheti. One such person was Davud Khan, the brother of Simon I of Kartli (ruled 1556–1569, 1578–1599). Son of Levan of Kakheti, Prince Jesse also visited Qazvin in the 1560s and converted to Islam. In return, Tahmasp gave him gifts and special treatment. The prince was given the old royal palace in Qazvin to live in and became the governor of Shaki and nearby areas. The conversion of these Georgian princes did not stop the Georgian forces who tried to take back Tbilisi under Simon I and his father, Luarsab I of Kartli, in the Battle of Garisi. The battle ended with no clear winner, and both Luarsab and the Safavid commander Shahverdi Sultan were killed.

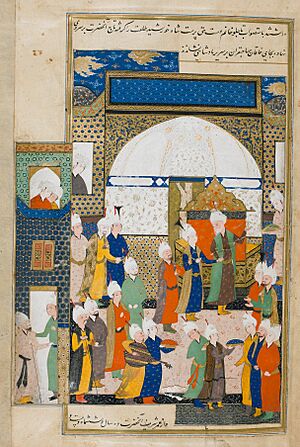

Royal Visitors and Guests

One of the most famous events of Tahmasp's rule was the visit of Humayun (ruled 1530–1540), the oldest son of Babur (ruled 1526–1530) and emperor of the Mughal Empire. Humayun was facing rebellions from his brothers. He fled to Herat, traveled through Mashhad, Nishapur, Sabzevar, and Qazvin, and met Tahmasp at Soltaniyeh in 1544. Tahmasp treated Humayun with honor as a guest and gave him a beautifully illustrated version of Saadi's Gulistan from the time of Abu Sa'id Mirza (ruled 1451–1469, 1459–1469), Humayun's great-grandfather. However, Tahmasp refused to give him military help unless Humayun converted to Shia Islam. Humayun reluctantly agreed but went back to Sunni Islam when he returned to India. Still, he did not force the Iranian Shias who came with him to India to convert. Tahmasp also demanded that the city of Kandahar be given to his infant son, Morad Mirza, in return for his help. Humayun spent the Nowruz (New Year) festival at the Shah's court and left in 1545 with an army provided by Tahmasp to regain his lost lands. His first victory was Kandahar, which he gave to the young Safavid prince. However, Morad Mirza soon died, and the city became a point of disagreement between the two empires. The Safavids claimed it was given to them forever, while the Mughals said it was a temporary gift that ended with the prince's death. Tahmasp began the first Safavid expedition to Kandahar in 1558, after Humayun's death, and took the city back.

Another important visitor to Tahmasp's court was Şehzade Bayezid, an Ottoman prince who was running away. He had rebelled against his father, Suleiman the Magnificent. Bayezid came to the Shah in the autumn of 1559 with 10,000 soldiers to try and convince Tahmasp to start a war against the Ottomans. Although Tahmasp honored Bayezid, he did not want to break the Peace of Amasya. Suspecting that Bayezid was planning a takeover, Tahmasp had him arrested and sent back to the Ottomans. Bayezid and his children were immediately executed.

Later Years and Death

Even though Tahmasp rarely left Qazvin from the Peace of Amasya in 1555 until his death in 1576, he remained active during this time. A rebellion in Herat in 1564 was stopped by Masum Bek and the Khorasan governors, but the region remained troubled and was attacked by the Uzbeks two years later. Tahmasp became very ill in 1574 and almost died twice in two months. Since he had not chosen a crown prince, the question of who would rule next was raised by members of the royal family and Qizilbash leaders. His favorite son, Haydar Mirza, was supported by the Ustajlu tribe and the powerful Georgian group in the court. The imprisoned prince Ismail Mirza was supported by Pari Khan Khanum, Tahmasp's influential daughter. The group supporting Haydar tried to get rid of Ismail by winning over the commander of Qahqaheh Castle (where Ismail was imprisoned). But Pari Khan found out about the plan and told Tahmasp. The shah, who still cared for his son, ordered him to be guarded by Afshar musketeers.

Tahmasp recovered from his illness and went back to governing. However, tensions in the court led to another civil war when the shah died on May 14, 1576, from poisoning. The poisoning was blamed on Abu Naser Gilani, a doctor who treated Tahmasp when he was sick. According to a historical book, Abu Nasr was accused of betrayal in his treatment, and he was killed inside the palace by royal guards. Tahmasp I had the longest reign of any Safavid ruler, just nine days short of fifty-two years. He died without naming an heir, and the two groups in his court fought for the throne. Haydar Mirza was killed not long after his father's death, and Ismail Mirza became king, crowned as Ismail II (ruled 1576–1577). Less than two months after becoming king, Ismail ordered the killing of almost all male members of the royal family. Only Mohammad Khodabanda, who was almost blind, and his three young sons survived this terrible event.

Tahmasp's Policies

Government and Diplomacy

After the civil wars among the Qizilbash leaders, Tahmasp's rule became a "personal rule" where he tried to control the Turkoman influence by giving more power to the Persian government officials. A key change was the appointment of Qazi Jahan Qazvini in 1535. He expanded diplomacy beyond Iran by making contact with the Portuguese, the Venetians, the Mughals, and the Shia Deccan sultanates. The English explorer Anthony Jenkinson, who visited the Safavid court in 1562, also wanted to promote trade. The Habsburgs were eager to team up with the Safavids against the Ottomans. In 1529, Ferdinand I (ruled 1558–1564) sent a messenger to Iran to plan a two-sided attack on the Ottoman Empire the next year. However, the mission failed because the messenger took over a year to return. The first surviving Safavid letters to a European power were sent in 1540 to Doge of Venice Pietro Lando (ruled 1538–1545). In response, the Doge and the Great Council of Venice sent Michel Membré to visit the Safavid court. In 1540, he visited Tahmasp's camp at Marand, near Tabriz. Membré's mission lasted for three years, during which he wrote Relazione di Persia, one of the few European sources that describe Tahmasp's court. In his letter to Lando, Tahmasp promised to "cleanse the earth of [Ottoman] wickedness" with the help of the Holy League. However, this alliance never worked out.

One of the most important events of Tahmasp's reign was moving the Safavid capital. This started what is known as the Qazvin period. Although the exact date is not certain, Tahmasp began preparing to move the royal capital from Tabriz to Qazvin during a time of ethnic resettlement in the 1540s. Moving from Tabriz to Qazvin ended the old Turkoman-Mongol tradition of moving between summer and winter grazing lands with their herds. This also ended Ismail I's nomadic way of life. The idea of a Turkoman state centered in Tabriz was replaced by an empire centered on the Iranian plateau. Moving to a city that connected the empire to Khorasan through an ancient route allowed for more central control. Distant provinces like Shirvan, Georgia, and Gilan were brought more closely into the Safavid system. Bringing Gilan into the empire was especially important for the Safavids. To make sure he had permanent control over the province, Tahmasp arranged royal marriages with powerful families in Gilan. Qazvin's population, which was not Qizilbash, allowed Tahmasp to bring new people into his court who were not related to the Turkoman tribes. The city, known for its traditional and stable government, grew under Tahmasp's support. The most famous building from this time is Chehel Sotoun.

With the change of capitals, a new era in history writing began under Tahmasp's rule. Safavid history writing, which until then relied only on historians outside of Safavid influence, grew and became an important project in Tahmasp's new court. Tahmasp is the only Safavid ruler to have written down his memories, known as Tazkera-ye Shah Tahmasb. On the shah's behalf, Abdi Beg Shirazi, a secretary in the royal office, wrote a world history called Takmelat al-akhbar, which he dedicated to Pari Khan Khanum, Tahmasp's daughter. Although it was meant to be a world history, only the last part of the book, which covers the reigns of Ismail I and Tahmasp up until 1570, was published. He also asked Abol-Fath Hosseini to rewrite Safvat as-safa, the oldest surviving text about Safi-ad-din Ardabili and the Sufi beliefs of the Safavids. This was done to prove his claim of being a descendant of the prophet. All the historians supported by Tahmasp focused their works on one main goal: to tell the history of the Safavid dynasty. They called themselves 'Safavid' historians, living in a Safavid period of Iranian history. This idea had not been seen in earlier writings about the dynasty. This new way of thinking came from the change of the capital and the Safavid nomadic lifestyle becoming more urban. Historians like Charles Melville and Sholeh Quinn see Tahmasp's reign as the start of the "real flourishing of Safavid history writing."

Military Changes

The Safavid military changed during Tahmasp's rule. The first groups of gunners (tupchiyan) and musketeers (tufangchiyan), which started during Ismail I's reign, became more common in his army. A court record of the Battle of Jam and a military review in 1530 show that the Safavid army had several hundred light cannons and several thousand foot soldiers. Military slaves (Gollar-aghasis), developed by Tahmasp from prisoners from the Caucasus, commanded the musketeers and gunners. To reduce the power of the Qizilbash, he stopped using the titles of military commander and deputy to the king. The commander of the royal bodyguards (qurchi-bashi), who used to be under the military commander, became the chief Safavid military officer.

After the Peace of Amasya in 1555, Tahmasp became very greedy. He did not care how his troops got their pay, even if it was through illegal ways. By 1575, Iran's troops had not been paid for four years. People said they accepted this because, as one writer put it, 'they loved the shah so much'.

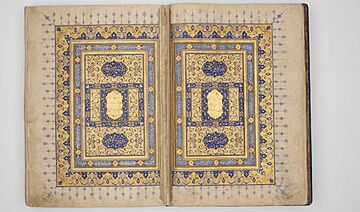

Religious Beliefs

Tahmasp described himself as a "pious Shia mystic king." His religious views and how much they affected Safavid religious policy are very interesting to historians. As the Italian historian Biancamaria Scarcia Amoretti noted, "the modern originality of Persian Shi'ism has its roots [with Shah Tahmasp]." Until 1533, the Qizilbash leaders, who worshipped Ismail I as the promised Mahdi, urged the young Tahmasp to follow in his father's footsteps. That year, he had a spiritual change, performed an act of repentance, and banned irreligious behavior. Tahmasp rejected his father's claim of being a mahdi. He became a devoted follower of Ali and a king who followed Islamic law (sharia). However, he still enjoyed villagers traveling to his palace in Qazvin to touch his clothing. Tahmasp strongly believed in the soon coming of the Mahdi. He refused to let his favorite sister, Shahzada Sultanim, marry because he was saving her as a bride for the Mahdi. He claimed connections with Ali and Sufi saints, like his ancestor Safi al-Din, through dreams where he saw the future. Tahmasp also had other superstitious beliefs, such as his strong interest in the occult science of geomancy. According to the Venetian diplomat, Vincenzo degli Alessandri, the shah was so dedicated to practicing geomancy that he had not left his palace for ten years. He also noted that Tahmasp was worshipped by his people as a god-like being, even though he had a weak and old body. Tahmasp wanted the poets in his court to write about Ali, rather than about him. He sent copies of the Quran as gifts to several Ottoman sultans. In total, during his rule, eighteen copies of the Quran were sent to Istanbul, and all were decorated with jewels and gold.

Tahmasp saw Twelverism as a new way of kingship. He gave religious leaders (ulama) authority in religious and legal matters and appointed Shaykh Ali al-Karaki as the representative of the Hidden Imam. This gave new political and court power to the religious scholars (mullahs), descendants of the prophet (sayyids), and their networks, connecting Tabriz, Qazvin, Isfahan, and the newly added centers of Rasht, Astarabad, and Amol. As noted by Iskandar Beg Munshi, the court historian, the sayyids as a group of wealthy landowners had significant power. During the 1530s and 1540s, they dominated the Safavid court in Tabriz. According to Iskandar Beg, "any wish of theirs was translated into reality almost before it was uttered… although they were guilty of unlawful practices." During Tahmasp's reign, Persian scholars accepted the Safavid claims to be descendants of the prophet and called him "the Husaynid" (a descendant of Husayn). Tahmasp started a large city program to make Qazvin a center of Shia piety and traditional beliefs. He expanded the Shrine of Husayn (son of Ali al-Rida, the eighth Imam). He also paid attention to his ancestral Sufi order in Ardabil, building the Janat Sarai mosque to encourage visitors and hold Sufi spiritual ceremonies (Sama). Tahmasp ordered the practice of Sufi rituals and had Sufis and religious scholars come to his palace to perform public acts of devotion and Islamic meditation (zikr) for Eid al-Fitr (and renew their loyalty to him). This encouraged Tahmasp's followers to see themselves as part of a community too large to be limited by tribal or local social groups. Although Tahmasp continued the Shia conversion in Iran, unlike his father, he did not force other religious groups to convert. He had a long-standing respect for and support of Christian Armenians.

Arts and Culture

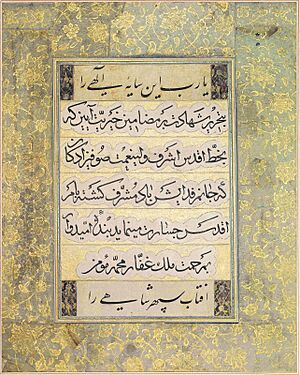

In his youth, Tahmasp was interested in calligraphy and art and supported masters in both. His most important contribution to Safavid arts was his support for Persian miniature manuscripts, which happened during the first half of his rule. He was the person for whom one of the most famous illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh was named. This work was started by his father around 1522 and finished in the mid-1530s. He encouraged painters like Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, creating a royal painting workshop for masters, experienced artists, and apprentices. They used special materials like ground gold and lapis lazuli. Tahmasp's artists illustrated the Khamsa of Nizami, and he worked on the balcony paintings of Chehel Sotoun. The Tarikh-e Alam-ara-ye Abbasi calls Tahmasp's reign the peak of Safavid calligraphic and pictorial art. Tahmasp lost interest in miniature arts around 1555 and, because of this, closed the royal workshop and allowed his artists to work elsewhere. However, his support of the arts has been praised by many modern art historians like James Elkins and Stuart Cary Welch. The American historian, Douglas Streusand, calls him 'the greatest Safavid patron'. Colin P. Mitchell connects Tahmasp's support with the rebirth of Iranian artistic and cultural life.

The reigns of Tahmasp and his father, Ismail I, are seen as the most productive time for the Azeri Turkish language and literature. The famous poet, Fuzuli, who wrote in Azeri Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, thrived during this era. In his own writings, Tahmasp mentions his love for both Persian and Turkish poetry. According to Tazkera-ye Tohfe-ye Sāmi by his brother, Sam Mirza, there were 700 poets during the reigns of the first two Safavid kings. After Tahmasp's religious conversion, many poets joined Humayun. Other poets like Naziri Nishapuri and 'Orfi Shirazi chose to leave Iran and move to the Mughal court. There, they started a new style of poetry called Indian-style poetry (Sabk-i Hindi), known for its rich language, metaphors, mystical and philosophical themes, and allegories.

Money and Coins

Tahmasp I's coins were different depending on where they were made. The akçe was used in Shirvan. In Mazandaran, the tanka was minted, and Khuzestan used the larin currency. By the 1570s, most of these independent money systems were combined. The weight of the shahi coins (Safavid silver coins) decreased a lot. They went from 7.88 grams at the beginning of Tahmasp's rule to 2.39 grams in the western parts of the empire and 2.92 grams in the east by the end. These weight reductions were due to Ottoman and Uzbek invasions, as well as the Ottoman trade ban, which hurt trade and, therefore, the shah's income. According to the Venetian Michel Membré, no merchant could travel to Iran through Ottoman borders without permission from the sultan. All travelers were stopped and arrested if they did not have a royal permit.

On his coins, Arabic was no longer the only language used. On his fals (folus-i shahi) coins, the phrase "May be eternally [condemned] to the damnation of God / He, who alters [the rate of] the royal folus" is written in Persian. Old copper coins were re-released with new marks like folus-i shahi or adl-e shahi, which showed their new value.

Family Life

| Ancestors of Tahmasp I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unlike his ancestors who married Turkomans, Tahmasp married women from Georgia and Circassia. Most of his children had mothers from the Caucasus. His only Turkoman wife was his chief wife, Sultanum Begum from the Mawsillu tribe (a marriage for political reasons). She gave birth to two sons: Mohammad Khodabanda and Ismail II. Tahmasp had a difficult relationship with Ismail, whom he imprisoned because he suspected his son might try to take over. However, he cared for his other children. He ordered that his daughters be taught about government, art, and learning. Haydar Mirza (his favorite son, born to a Georgian slave) took part in state affairs.

Tahmasp had seven known wives:

- Sultanum Begum (around 1516–1593 in Qazvin), Tahmasp's main wife, from the Mawsillu tribe. She was the mother of his two older sons.

- Sultan-Agha Khanum, a Kumyk, sister of Shamkhal Sultan Cherkes (governor of Sakki). She was the mother of Pari Khan Khanum and Suleiman Mirza.

- Sultanzada Khanum, a Georgian slave, mother of Haydar Mirza.

- Zahra Baji, a Georgian, mother of Mustafa Mirza and Ali Mirza.

- Huri Khan Khanum, a Georgian, mother of Zeynab Begum and Maryam Begum.

- A sister of Waraza Shalikashvili.

- Zaynab Sultan Khanum (married 1549; died in Qazvin October 1570 and buried in Mashhad), widow of Tahmasp's younger brother Bahram Mirza.

He had thirteen sons:

- Mohammad Khodabanda (1532 – 1595 or 1596), Shah of Iran (ruled 1578–1587).

- Ismail II (May 31, 1537 – November 24, 1577), Shah of Iran (ruled 1576–77).

- Murad Mirza (died 1545), a governor of Kandahar in name; died as a baby.

- Suleiman Mirza (died November 9, 1576), Governor of Shiraz, killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Haydar Mirza (September 28, 1556 – May 15, 1576), declared himself Shah of Iran for one day after Tahmasp's death; killed by his guards in Qazvin.

- Mustafa Mirza (died November 9, 1576), killed during Ismail II's purge; his daughter married Abbas the Great.

- Junayd Mirza (died 1577), killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Mahmud Mirza (died March 7, 1577), governor of Shirvan and Lahijan, killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Imam Qoli Mirza (died March 7, 1577), killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Ali Mirza (died January 31, 1642), blinded and imprisoned by Abbas the Great.

- Ahmad Mirza (died March 7, 1577), killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Murad Mirza (died 1577), killed during Ismail II's purge.

- Zayn al-Abedin Mirza, died in childhood.

- Musa Mirza, died in childhood.

Tahmasp likely had thirteen daughters, eight of whom are known:

- Gawhar Sultan Begum (died 1577), married Sultan Ibrahim Mirza.

- Pari Khan Khanum (died 1578), died by the orders of Khayr al-Nisa Begum.

- Zeynab Begum (died May 31, 1640), married Ali-Qoli Khan Shamlu.

- Maryam Begum (died 1608), married Khan Ahmad Khan.

- Shahrbanu Khanum, married Salman Khan Ustajlu.

- Khadija Begum (died after 1564), married Jamshid Khan (grandson of Amira Dabbaj, a local ruler in western Gilan).

- Fatima Sultan Khanum (died 1581), married Amir Khan Mawsillu.

- Khanish Begum, married Shah Nimtullah Amir Nizam al-Din Abd al-Baqi (leader of the Ni'matullāhī order).

Tahmasp's Legacy

Tahmasp I's rule began during a time of civil wars among the Qizilbash leaders after the death of Ismail I. Ismail I was seen as a charismatic leader, almost like a Messiah, which made the Qizilbash follow him. But this ended with Tahmasp becoming shah. Unlike his father, Tahmasp did not have the same inspiring personality, nor was he old enough to be a fierce warrior, a quality the Qizilbash valued. However, Tahmasp did overcome these challenges. He proved himself a capable military commander in the Battle of Jam against the Uzbeks. Instead of fighting the Ottomans directly, he preferred to attack their armies from behind. His ability to survive against the much larger Ottoman army shows he was a master of clever military tactics. Tahmasp knew he could not replace his father as a spiritual leader. While he worked to restore his family's right to rule among the Qizilbash, he also had to create a public image for himself to convince the wider population of his right to be the new Safavid shah. So, he became a very devout follower of Shi'ism and kept this image of strong religious devotion until the end of his rule. This religious image helped him break the power of the Qizilbash. He was able to take full control of the empire within ten years, after the country had been through civil war among the plotting tribal chiefs. He thus set a standard public image for Safavid kings: a very religious monarch who acted as a representative of the Hidden Imam. However, none of his successors kept this image as strongly as he did. Even after gaining full power, Tahmasp had less political influence compared to the Ottoman Empire. However, he successfully laid the groundwork for Abbas the Great's transformation of the Safavid government by bringing people from the Caucasus into his empire as slaves. He created the core of the force that changed the political balance of the empire during his grandson's time.

Tahmasp I did not make a big impression on Western historians, who often compared him to his father. He is sometimes described as a "miser" (someone who hates spending money) and a "religious fanatic." This description has made Tahmasp an unclear figure as a king and a person. However, there are several instances recorded by historians of his time that show the more positive sides of the shah's character. For example, despite his greed, his religious devotion led him to give up taxes worth about 30,000 tomans because collecting them would go against religious law. His speech to the messengers of Suleiman the Magnificent, who had come to take back the runaway prince Şehzade Bayezid, showed his political skill. He supported the arts and had a very cultured mind. According to Colin P. Mitchell, it is a great achievement that he was able to not only keep his father's empire from falling apart but also expanded it, while ruling at the same time as Suleiman the Magnificent, the most successful Ottoman sultan. It was during Tahmasp's reign that the Safavid right to rule was established and gradually accepted among the Shia people, who liked the idea of a descendant of the prophet's family (Ahl al-Bayt) ruling over them. Thus, the Safavid dynasty gained a much stronger reason to rule than just winning wars. By the end of his reign, Tahmasp's success in keeping the empire together allowed the Persian government officials to take on the role of managing the Safavid empire. This allowed Tahmasp and his successors to gain a strong right to rule and to create a powerful image of the emperor that prevented another civil war, even when the empire was at its weakest.

See also

In Spanish: Tahmasp I para niños

In Spanish: Tahmasp I para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |