Battle of Nieuwpoort facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Nieuwpoort |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

Prince Maurice at the Battle of Nieuwpoort by Pauwels van Hillegaert. Oil on canvas |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 infantry 1,400 cavalry 14 guns |

10,000 infantry 1,200 cavalry 9 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,700-2,700 dead or wounded | 4,000 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

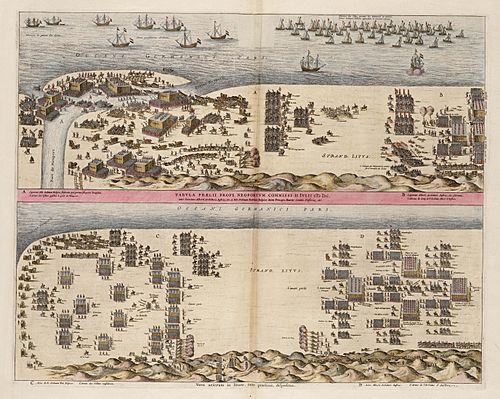

The Battle of Nieuwpoort was a major fight that happened on July 2, 1600. It took place near the town of Nieuwpoort during the Eighty Years War and the Anglo-Spanish War. In this battle, Dutch and English soldiers faced off against experienced Spanish troops. Even though one side of their army almost broke, the Dutch and English managed to attack with both foot soldiers and cavalry. The Spanish army eventually scattered, leaving their cannons behind.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

This battle was a clash between two important military leaders. On one side was Maurice, Count of Nassau, leading the armies of the Dutch Republic. On the other side was Albert, Duke of Burgundy, leading the armies of the Habsburg Netherlands (which was controlled by Spain).

Maurice, born in 1567, was the son of William of Orange, who started the Dutch rebellion against Spain. Maurice had been fighting since he was young. In the years before this battle, he completely changed the Dutch army. He introduced new ways of training soldiers and giving commands. He also made sure equipment was the same for everyone and kept careful records. This made his army very organized, reliable, and strong. They had powerful firepower, deadly cavalry, and experienced officers.

Albert, born in 1559, was related to the King of Spain, King Philip II. He ruled the Spanish Netherlands with his wife, Philip's daughter Isabella. Albert didn't have much experience leading armies. The Spanish army was also very experienced, but some of their top commanders were not as skilled.

A big problem for the Spanish army was that many soldiers hadn't been paid in a long time. This led to many mutinies, which means soldiers rebelled against their commanders. Several groups of mutineers even set up their own small "republics" near the Dutch border.

The Plan to Attack Dunkirk

Maurice used these problems in the Spanish army to capture some important forts. One of these was Fort Crevecoeur. Its soldiers had mutinied but still fought for Spain. After a two-month siege, Maurice captured it in May 1600. He even offered the Spanish soldiers their unpaid wages if they joined the Dutch army, which they did.

This easy victory made the Dutch government want to try something bigger. They decided to attack Dunkirk. Dunkirk was a major Spanish port in the north. Spanish ships from Dunkirk caused a lot of damage to Dutch merchant ships and fishermen. Capturing it would also give the Dutch an advantage in talks with France and England.

However, Dunkirk was a difficult target. Two earlier attempts to land an army nearby had failed. A safer plan was to use the Dutch-held city of Ostend as a base. Only two things stood between Ostend and Dunkirk: Fort Albert and the city of Nieuwpoort. The plan was to land the army right in front of Nieuwpoort, capture it and the fort, and then march to Dunkirk.

Maurice and his military leaders didn't fully agree with the government's plan. They preferred to attack Sluis, another Spanish port. Sluis was closer to the Dutch Republic and important for controlling sea access to the major trade center of Antwerp. But the government insisted on Dunkirk.

Maurice's March to Battle

By June 21, Maurice had gathered a large army. It had about 12,000 foot soldiers and 2,000 cavalry (soldiers on horseback). The next day, he crossed the Scheldt River and moved to Ostend, his main base. On June 30, he started marching towards Nieuwpoort.

When Maurice reached Nieuwpoort on July 1, he sent two-thirds of his army across the Yser River to block the city from the west. That night, while preparing for a siege, he heard that Archduke Albert's army was very close. Maurice realized he was cut off from his base. He ordered his cousin, Ernst Casimir (Ernst Casimir I of Nassau-Dietz), to slow down the Spanish troops. Meanwhile, Maurice quickly moved the main part of his army back across the Yser River to face the Archduke. He had no choice but to fight.

Ernst Casimir, with his Scottish and Dutch regiments, cavalry, and two cannons, was ordered to capture the Leffinghen bridge. But when he arrived, the Spanish already held it. Ernst tried to hold them back, but the Spanish were too strong. They charged and broke through his soldiers. His cavalry fled in a panic. More than 600 Scottish soldiers were killed. Ernst's force was almost completely destroyed.

After this easy victory, Archduke Albert met with his captains. Most of them wanted to dig in and wait for Maurice to attack them in a narrow area. This would make it hard for the Dutch cavalry to fight. However, the mutineer soldiers, who had joined Albert's army because he promised them plunder, wanted to fight right away. They convinced the Archduke to advance. The Spanish army marched along the coast. The tide was coming in, forcing them to climb slowly up the slippery sand dunes. Maurice just had enough time to get his whole army ready to face the Archduke.

The Battle Begins

Maurice placed his best regiments in a strong defensive spot on top of the sand dunes. His cannons were set up to fire along both sides of the enemy lines. The English soldiers, led by the experienced Francis Vere, were the first line of infantry. They waited on the dunes for the Spanish army to arrive.

The Spanish sent 500 harquebusiers (soldiers with early firearms) to cover their advance. But two unruly mutineer regiments in the front quickly charged up the hill. They were pushed back in disorder. The Spanish light cavalry was also defeated by the Dutch cuirassiers (heavy cavalry). Then, the second line of Spanish infantry attacked. The Sapena and Ávila Tercios (Spanish army units) quickly gained ground against the Dutch on the right side. Maurice sent his entire second line to help, which stabilized the front.

Meanwhile, an Anglo-Dutch fleet offshore moved close to the coast. They fired cannons at the Spanish positions, helping the land forces. Maurice then sent most of his cavalry against the Spanish side. The Dutch cuirassiers easily defeated the lighter Spanish cavalry. The mutineer cavalry, who had just regrouped, fled the battlefield and never returned. However, the Dutch cavalry was stopped by the Spanish third line of infantry and had to retreat with heavy losses.

On the Dutch left, the English regiments faced the very experienced Spanish tercios of Monroy and Villar. These were the best of the Spanish foot soldiers. The English, who were well-trained in Maurice's new tactics, kept firing at the Spanish. The Spanish advanced steadily up the slope, protected by their skirmishers. The fight was even for a while. Eventually, in a close-quarters fight with pikes, the Spanish pushed the English off the top of the hill. Francis Vere saw that the English line might collapse. He asked for help, but it didn't arrive in time, and the English were finally forced to retreat.

However, the Spanish soldiers were tired from a day of fighting and marching on difficult ground. They advanced very slowly. Even worse, their units became mixed up. Maurice noticed this and sent his reserve cavalry, only three troops strong, against them. Their attack was surprisingly successful. The Spanish were thrown into confusion and began a slow retreat. Vere, who had managed to gather some English companies behind a cannon battery, rejoined the fight. He was also reinforced by fresh regiments. Finally, Vere sent his own cavalry against the Spanish, who were now under heavy attack and retreated in disorder.

On the Dutch right, Archduke Albert had sent his third line into the attack. Maurice saw his chance and asked his tired cavalry for one last effort. Under the command of his cousin Louis, another charge was made, and the Spanish cavalry was finally driven from the field. The Spanish infantry, already fighting at the front, could not stop this new attack on their side. They began to give ground. After a while, their front broke, and all their units ran in confusion, leaving their cannons behind. The survivors scattered, but the Dutch soldiers in Ostend did not pursue them, which allowed the Spanish army to avoid being completely destroyed.

After the Battle

The Spanish suffered heavy losses. Between 2,500 and 4,000 soldiers were killed or wounded, and about 600 were captured. Many officers were lost, and their best units suffered greatly. They also lost all their cannons. The Dutch and English captured ninety Spanish flags. The flags lost by the Scots and Zeelanders at Leffinghen were also taken back.

The Dutch and English also had many losses, between 1,700 and 2,700 soldiers killed or wounded. This included the soldiers lost at Leffinghen. The British forces, who faced the strongest Spanish attacks, lost nearly 600 men. However, their bravery showed the Dutch that they could be relied on in battle.

Maurice's army stayed in Nieuwpoort for two weeks. Even though they had won a rare victory against a Spanish army in an open battle, the battle didn't achieve much more. The Dutch did not go on to capture Dunkirk, which was the main goal of the campaign. Their supply lines were stretched too thin. Maurice soon had to pull his army back from Spanish territory. The local people, the Flemish, whom Maurice hoped would join his revolt, remained loyal to Spain. Ships from Dunkirk continued to attack Dutch and English trade. Instead, the allied army went to Ostend and captured a large Spanish fort called 'Isabella'.

A key lesson from this battle was that it was often better to besiege and capture towns than to fight big battles in open fields. This idea became more important in the Eighty Years' War after this battle. While Maurice's army beat a Spanish army, his reformed infantry had been pushed back from a strong position by the Spanish infantry using their old methods. It was only his cavalry that saved him from defeat. The Battle of Nieuwpoort is seen as the first time the dominance of the Spanish tercios (their famous infantry units) was truly challenged in warfare. Spanish military experts quickly noticed Maurice's new tactics. They even started to use more light cavalry in their own army.

News of the victory reached England. Queen Elizabeth I was very happy. She often told her courtiers that Francis Vere was "the worthiest captain of our time." Several songs and poems were written to celebrate the victory in England. Meanwhile, Isabella, the Archduke's wife, was disappointed by the defeat but relieved that her husband had escaped safely.

Armies at Nieuwpoort

Dutch States Army

- First Line

- Horace Vere Regiment (English soldiers)

- Francis Vere Regiment (English soldiers)

- Hertinga Regiment (Frisian soldiers, a very large regiment)

- 6 groups of Cuirassiers (heavy cavalry)

- 3 groups of Light Cavalry

- Second Line

- Domerville Regiment (French Huguenot mercenaries)

- Swiss Battalion (4 companies of Swiss mercenaries)

- Marquette Regiment (Walloon soldiers, made up of Spanish deserters)

- 6 groups of Cuirassiers

- Third Line

- Ernst Casimir I of Nassau-Dietz Regiment (German soldiers)

- Hurchtenburch (Dutch soldiers)

- Ghistelles (Dutch soldiers)

- 3 groups of Cuirassiers

Spanish Army

- First Line

- 1st Provisional Tercio (Spanish soldiers)

- 2nd Provisional Tercio (Walloon soldiers)

- 7 groups of light cavalry

- Second Line

- Monroy Tercio (Spanish soldiers)

- Villar Tercio (Spanish soldiers)

- Sapena Tercio (Spanish soldiers)

- Avila Tercio (Italian soldiers)

- 1 group of Light Lancers

- 5 groups of Cuirassiers

- Third Line

- La Barlotte Tercio (Walloon soldiers)

- Bucquoy Tercio (Walloon soldiers)

- Bostock Regiment (English deserters and English Catholics)

- 6 groups of Light Cavalry

|

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Nieuwpoort para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Nieuwpoort para niños