Witch trials in early modern Scotland facts for kids

In early modern Scotland, between the early 1500s and mid-1700s, many people were put on trial for the crime of witchcraft. These trials were part of a bigger series of witch trials happening across Europe at the time.

Before the 1500s, there were only a few cases where people were accused of using magic to cause harm. But in 1563, a new law called the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or even talking to witches, a crime punishable by death.

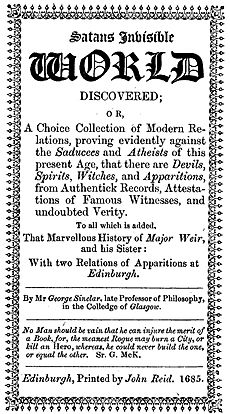

The first big trials under this new law were the North Berwick witch trials, which started in 1590. King James VI was very involved, believing he was a "victim" of witchcraft. He became very interested in the topic and even wrote a book called Daemonologie in 1597, defending the hunting of witches. However, over time, he seemed to become less convinced and eventually tried to limit the number of trials.

It's thought that between 4,000 and 6,000 people were tried for witchcraft in Scotland during this time. Most of them were from the Scottish Lowlands. This was a much higher number compared to nearby England. About 75% of those accused were women. Experts believe that more than 1,500 people were executed.

The witch hunts slowed down when England occupied Scotland in the 1650s, during the time of Oliver Cromwell. But they started up again after the king returned in 1660. This caused some worry, and the Privy Council of Scotland (a group of royal advisors) began to limit arrests, trials, and the use of torture. People also started to become more doubtful about witchcraft in the late 1600s. Also, some problems like money troubles, which might have led to accusations, became less severe.

Even though there were still a few local witch hunts, the last known executions happened in 1706, and the last trial was in 1727. When the Scottish and English parliaments joined together in 1707, the new British parliament eventually removed the 1563 Witchcraft Act in 1736.

Many reasons have been suggested for why these hunts happened, including money problems, changing ideas about women, the rise of a very religious government, the Scottish legal system, the use of torture, the role of the local church, and the belief in making a deal with the Devil. Historians often say that it was a mix of many things, not just one single cause.

Contents

Why Did the Witch Hunts Start?

Early Legal Cases

In the past, there were a few cases in Scotland where people were accused of using magic to cause harm. For example, in 1479, John Stewart, Earl of Mar was accused of using magic against his brother, King James III. However, these types of political cases became less common in the early 1500s.

Most people in the Middle Ages believed in magic. But religious leaders and lawyers usually only cared about cases where magic was clearly used to hurt someone. In 1542, three women from Edinburgh and Dunfermline were accused of witchcraft and burned. They were said to have used harmful magic and to have predicted the future.

How Beliefs Changed

From the late 1500s, ideas about witches began to change. People started to believe that witches got their powers from the Devil, making witchcraft a type of heresy (a belief against official religious teachings). Both Catholics and Protestants widely accepted these ideas.

After the Reformation in 1560, the Scottish Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563. This law, similar to one in England, made practicing witchcraft or talking to witches a crime punishable by death.

The first witch hunt under this new law happened in eastern Scotland in 1568–69. There were attempts to link witches to the Devil, but the hunt eventually stopped. In 1574, the Earl of Argyll held courts in western Scotland and executed people for "common sorcery."

King James VI's Role

When King James VI visited Denmark in 1589, he saw that witch hunts were common there. This might have made him more interested in witchcraft. He even thought that the bad storms he faced on his journey were caused by magic.

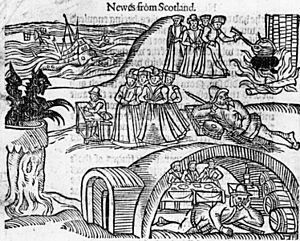

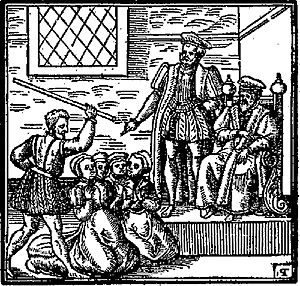

After returning to Scotland, he attended the North Berwick witch trials. This was the first major witch hunt in Scotland where people were successfully accused of making a deal with the Devil. Several people, like Agnes Sampson and a schoolmaster named John Fian, were found guilty of using witchcraft to create storms against the King's ship.

James became very worried about the threat of witches. He even believed that his cousin, Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell, was a witch. The King then set up royal groups to hunt down witches and suggested using torture on suspects. James himself watched the torture of women accused of being witches.

In 1597, inspired by his experiences, he wrote Daemonologie. This book was against witchcraft and even provided ideas for Shakespeare's play The Tragedy of Macbeth, which has famous Scottish witches.

James believed that women were weaker and more easily tricked by the Devil, which made them more likely to be witches. He thought that widespread belief in witches and their meetings with the Devil would reduce women's political power. However, after publishing Daemonologie, his views became more doubtful. In the same year, he stopped the special groups that hunted witches, limiting trials by the main courts.

How Were the Trials Carried Out?

Scotland had a much higher rate of witchcraft trials than England, even though its population was smaller. Most of these trials happened in the Scottish Lowlands, where the Kirk (the Scottish church) had more influence.

Big periods of trials included 1590–91 and the Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597, where at least 400 people were tried. About 200 of them were executed. Other major hunts happened in 1628–31 and 1649–50. The most intense witch hunt was in 1661–62, involving about 664 accused witches.

Most of the accused, about 75%, were women. However, some men were also executed as witches or warlocks. More than 1,500 people were executed in total. Most were older women, but some younger women and men were also accused, often because they were related to an accused witch. Some men were accused because they were folk healers who were thought to have misused their powers. Most accused witches were not homeless or beggars, but settled members of their communities. Many had a reputation for witchcraft over the years, leading to accusations when someone suffered bad luck, especially after a curse was made.

Almost all witchcraft trials took place in regular courts under the 1563 Act. In 1649, a religious group called the Covenanters passed a new law that made it a death penalty to consult with "Devils and familiar spirits."

There were three main types of courts for accused witches:

- The Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh, which handled cases from all over Scotland.

- circuit courts, led by judges from the main courts, held in different areas.

- Special local courts, set up by the Privy Council or Parliament, run by local landowners to try witches where they were accused.

Local courts had a much higher execution rate (about 90%) compared to the Justiciary Court (55%) and circuit courts (16%). After 1597, local church groups called kirk sessions often took over the hunt for witches, using it to target "superstitious" and Catholic practices.

Scottish witch trials were known for using "pricking." This involved piercing a suspect's skin with needles or pins. People believed that witches had a Devil's mark where they couldn't feel pain. Professional "prickers" like John Kincaid and John Dick helped start the witch hunt in 1661–62. But when they were found to be fakes and put in prison, it helped end the trials.

Torture was used in some important cases, like that of John Fine, who was accused of plotting against the king in 1590. However, these cases were rare. Confessions, which were seen as the best proof, were more often gotten by "waking" the witch. This meant keeping the suspect awake for a long time. After about three days, people often start to imagine things, and these hallucinations provided strange details in the trials.

What Did People Believe About Witches?

In early modern Scotland, everyone, rich or poor, believed that witches could cause harm. For example, in 1701, a woman named Elizabeth Dick was turned away from a mill when she was begging. She cursed the mill, and several people said the grain inside turned red. Only when someone who had refused her help gave her money did she bless the mill, and everything went back to normal. About half of the accused witches had already been known for causing harm for a long time.

It seems that healing skills were generally seen as different from witchcraft, as only a small number of accused witches were folk healers. Trials in Aberdeenshire in 1596 showed that people could buy spells from folk magicians for good fishing, happy marriages, long life, or to change the weather. But spells that caused harm were considered witchcraft. Witches and other folk magicians could also tell the future. For example, Margaret Mungo was accused of finding answers by seeing which way a sieve (a kitchen tool) swung when hung from scissors.

Many people believed that Scottish witchcraft was especially focused on making a deal with the Devil. In one high-profile case in 1675, Katherine Sands admitted to giving up her baptism and receiving the Devil's mark. However, in local trials, these demonic elements were less common.

Some historians note that in trials from Fife, the Devil was not a very important figure. Many stories of witch meetings sounded more like fairy gatherings, where dancing fairies would disappear if a human broke their circle, rather than evil meetings with Satan. Fairies were a big part of magical beliefs in Scotland.

Isobel Gowdie, a young wife from near Auldearn, was tried for witchcraft in 1662. She gave four statements without being tortured, which give us a very detailed look into magical beliefs in Britain. She said her witch group met on nearby Downie Hill, that they could turn into hares, and that the Queen of the Fairies had entertained her in her home under the hill. Some historians believe that in Scotland, popular beliefs in fairies mixed with the educated Christian ideas about the Devil.

Why Did the Hunts Stop?

In the 1600s, educated people in Scotland started to doubt whether witchcraft was real. Scotland was defeated by England in the Civil Wars and occupied by Oliver Cromwell's forces. In 1652, Scotland became part of a Commonwealth with England and Ireland, and the Privy Council and courts stopped working. The English judges who replaced them did not like using torture and often doubted the evidence it produced, which led to fewer trials.

To gain support, local Sheriff's courts and Justices of the Peace were brought back in 1656. This led to a new wave of witchcraft cases, with 102 cases between 1657 and 1659. However, when the king returned in 1660, the limits on trials were completely removed. This caused a huge number of over 600 cases, which worried the restored Privy Council. They then insisted that their permission was needed for any arrest or trial, and they banned judicial torture.

Trials began to decrease as judges and the government controlled them more strictly. Torture was used less often, and the rules for what counted as evidence became stricter. When the "prickers" were exposed as fakes in 1662, a major type of evidence was removed. The Lord Advocate George Mackenzie also worked to make trials less effective.

There might also have been a growing doubt among ordinary people. With more peace and stability, the money and social problems that might have led to accusations were reduced. Although there were still occasional local outbreaks, like in East Lothian in 1678 and Paisley in 1697.

The last executions recorded by the main courts were in 1706. The very last trial happened in a local court in Dornoch in 1727, but its legality was questioned. In 1736, the British parliament removed the 1563 Witchcraft Act, making it impossible to legally prosecute witches. However, basic magical beliefs still continued, especially in the Highlands and Islands.

Why So Many Trials in Scotland?

Historians have suggested various reasons for the Scottish witch hunts, and why they were more intense than in England. Older ideas, like there being a widespread pagan cult that was persecuted, or that witch hunts were caused by doctors trying to get rid of folk healers, are no longer believed by professional historians.

Most of the major periods of trials happened during times of serious money problems. Some accusations might have followed when people stopped giving help to those who were struggling, especially single women, who made up many of the accused.

The reformed Scottish church (Kirk) that appeared after 1560 was strongly influenced by Calvinism and Presbyterianism. It might have seen women as a greater moral threat. Because of this, the witch hunt in Scotland has been seen by some as a way to control women. However, two of the biggest witch hunts happened when the Church of Scotland was controlled by Episcopalians. One historian, Christina Larner, suggested that the start of the hunts in the mid-1500s was linked to the rise of a "godly state," where the reformed Kirk was closely connected to a Scottish government and legal system that became more involved in people's lives.

It has been suggested that the intensity of Scottish witch hunting was due to its legal system and the widespread use of torture. However, historian Brian P. Levack argues that the Scottish system was only partly like an inquisitorial system (where the court actively investigates) and that torture was used very little, similar to England. A relatively high number of people were found not guilty in Scottish trials, which might be because defence lawyers were used in Scottish courts, a benefit not given to accused witches in England.

The close involvement of the Scottish Kirk in trials and the local nature of Scottish courts, where local judges heard many cases (unlike England, where most cases went before a few circuit judges), might have led to more prosecutions. The idea of a deal with the Devil is often said to be a major difference between Scottish and English witchcraft cases. But some historians argue that the idea of Satan might have been forced onto local traditions by the central government, especially traditions about fairies, which were more common in Scotland than in England.

Because there are so many different explanations for the witch hunt, some historians now use the idea of "associated circumstances." This means it was a combination of many factors working together, rather than one single main cause.

Apologies in the 21st Century

In 2020 and 2021, centuries after the Witchcraft Act was removed, a group called "Witches of Scotland" campaigned to clear the names of those accused. A new bill in the Scottish parliament has the support of the Scottish government to do this.

On International Women's Day in 2022, Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, officially apologized on behalf of the Scottish government to all those accused under the Witchcraft Act.

The Kirk (Church of Scotland) also apologized in May 2022 for its part in the persecution of those accused of witchcraft.

See also

- Witch trials in England

- Survey of Scottish Witchcraft

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |