Covenanters facts for kids

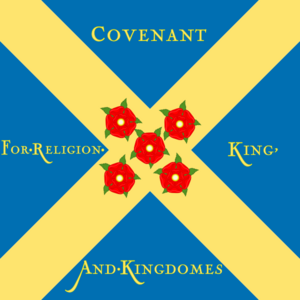

The Covenanters (Scottish Gaelic: Cùmhnantaich) were a Scottish religious and political group in the 1600s. They believed the Church of Scotland (called the kirk) should be run by its own leaders and not by the king. Their name comes from the word covenant, which means a special agreement with God.

The Covenanters' story began with disagreements between Scottish kings, James VI and his son Charles I, and the kirk. The kings wanted to control the church and appoint bishops. But many Scots wanted the church to be run by elected elders and ministers, a system called Presbyterianism.

In 1638, thousands of Scots signed the National Covenant. This was a promise to resist the changes King Charles I wanted to make to the kirk. After winning two wars against the king (the Bishops' Wars in 1639 and 1640), the Covenanters took control of Scotland.

In 1643, they signed another important agreement, the Solemn League and Covenant. This brought them into the First English Civil War on the side of the English Parliament. After King Charles I lost the war in 1646, he gave himself up to the Scottish Covenanters. He hoped to cause arguments between them and the English Parliament.

This led the Scots to support Charles in the Second English Civil War in 1648. After the king was executed in 1649, the Covenanter government made a deal with Charles's son, Charles II. This was the Treaty of Breda (1650). They agreed to help him become king again, and he promised to protect the Presbyterian Church in Scotland.

Charles II was crowned King of Scots in January 1651. But the Covenanter army was defeated by Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650. England then took over Scotland, and the Presbyterian Church lost its official status. People could worship freely, except for Roman Catholics.

When Charles II became king again in 1660 (this was called the Restoration), he broke his promises to the Covenanters. He brought back bishops and undid all the Covenanters' changes. Many ministers who refused to accept these changes lost their jobs. A new law, the Abjuration Act of 1662, made it illegal to support the Covenants.

This made many Covenanters very unhappy, leading to protests and violence. In 1679, there were battles at Drumclog and Bothwell Bridge. The Sanquhar Declaration of 1680 said that people could not accept a king who didn't respect their religion. King Charles II died in 1685, and his Catholic brother, King James VII, became king.

After 1660, the Covenanters were a group that was often persecuted. There were several armed rebellions. The time from 1679 to 1688 is known as "The Killing Time" because many Covenanters were killed. After the Glorious Revolution in Scotland in 1688, the Church of Scotland became Presbyterian again. Most Covenanters rejoined the church, and their movement became less powerful. Today, some churches, like the Reformed Presbyterian communion, continue their beliefs.

Contents

Why the Covenanters Formed

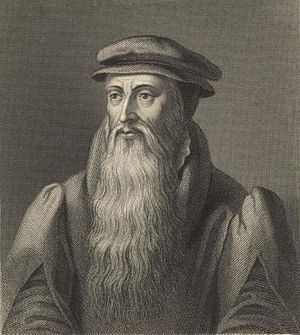

In the mid-1500s, John Knox and others created a new Church of Scotland. This church was Presbyterian, meaning it was run by elected elders and ministers. It followed the teachings of Calvin. Members of this new church promised to keep it as the only religion in Scotland. They made this promise in a "Covenant" or agreement with God.

In 1560, the Scottish Parliament accepted the Scots Confession. This document, mostly written by Knox, rejected many Catholic ideas. King James VI also agreed to this Confession. But James believed that as king, he was also the head of the church. He wanted to appoint bishops to lead the church. He famously said, "No bishops, no king."

However, others like Andrew Melville believed that Jesus Christ was the only head of the church. They thought the king was just a member of the church, ruled by its leaders. Even though James successfully put bishops in charge, the Scottish church remained Calvinist in its beliefs.

When James became king of England in 1603, he wanted to unite the churches of both countries. But Scottish bishops often disagreed with the Church of England's practices. They felt these practices were too similar to Catholicism.

Many Scots strongly disliked Catholicism. They had seen the terrible Thirty Years' War in Europe, a very destructive religious conflict. Scotland also had close ties with the Protestant Dutch Republic. This made Scots very sensitive to any changes in their church.

In 1636, the Scottish Church replaced its old rulebook with a new one called the Book of Canons. This book said anyone who disagreed with the King's power in church matters would be kicked out. Then, in 1637, a new Book of Common Prayer was introduced. This caused widespread anger and riots. A famous story says Jenny Geddes threw a stool at a minister during a service. Historians now think these protests were part of a planned effort against the new prayer book.

Wars and Changes

In February 1638, many Scots signed the National Covenant. This agreement promised to resist the king's new church rules. The Covenanters believed they were protecting their established religion, which they felt the king was trying to change. When the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland met in December 1638, it got rid of bishops. It also said the Assembly had the right to meet every year.

Most of Scotland supported the Covenant. King Charles tried to force his power in the Bishop's Wars of 1639 and 1640, but he lost. This left the Covenanters in charge of Scotland. When the First English Civil War started in 1642, the Scots first stayed neutral. But they sent troops to Ulster to help other Protestants there. This conflict made feelings stronger in Scotland and Ireland.

Covenanters believed a king was part of God's plan. So, they promised to "defend the king's person and authority." They couldn't imagine a government without a king. This idea was shared by many English Parliamentarians. They wanted to control the king, not remove him. But both sides in England disagreed about religious beliefs. In Scotland, almost everyone agreed on beliefs. The main argument was about who had the final say in church matters.

A Covenanter group led by Argyll thought uniting the churches of Scotland and England was best. In October 1643, they signed the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement promised a Presbyterian church union in return for Scottish military help. Some English leaders, like Oliver Cromwell, disagreed with this.

Over time, the Covenanters and their English allies started to see Cromwell's group as a bigger threat than the Royalists. When Charles surrendered in 1646, the Scots began talking about putting him back on the English throne. In 1647, Charles agreed to make England Presbyterian for three years. But he refused to sign the Covenant himself. This split the Covenanters into two groups: the Engagers and the Kirk Party.

The Covenanters lost the Second English Civil War. King Charles was executed in January 1649. The Kirk Party then took control in Scotland. In February 1649, the Scots declared Charles II King of Scotland and Great Britain. Under the Treaty of Breda, the Kirk Party agreed to help Charles become king of England again. In return, he accepted the Covenant.

But the Covenanters suffered defeats at Dunbar and Worcester. As a result, Scotland became part of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1652.

Life Under the Commonwealth

After their defeat in 1651, the Covenanters split into two main groups. Most ministers supported allowing Royalists back into the church. They were called "Resolutioners." The "Protestors" were a smaller group who blamed the defeat on making deals with the king's supporters. These groups disagreed on many things, including how the church should be run and religious freedom.

Oliver Cromwell, the English leader, decided he needed to reduce the power of Scottish nobles and the kirk. In 1652, new rules were made for Scotland. A new Council of Scotland was in charge of church matters. It also allowed freedom of worship for all Protestant groups. This meant Presbyterianism was no longer the official state religion. Church meetings still happened, but their rules were not enforced by law.

Most Covenanters did not like these changes. They refused to accept them. Scotland was officially joined with the Commonwealth on April 21, 1652.

The split between Resolutioners and Protestors grew worse. In 1653, both groups held their own church meetings in Edinburgh. The English military commander in Scotland stopped both meetings. The main church assembly would not meet again until 1690. The Resolutioners held informal meetings, while Protestors held outdoor meetings called conventicles.

When Cromwell's government (the Protectorate) was set up in 1654, its leader in Scotland, Lord Broghill, faced a problem. He said, "the Resolutioners love Charles Stuart and hate us, while the Protesters love neither him nor us." Neither Covenanter group wanted to work with the Protectorate.

Since the Resolutioners controlled most churches, Broghill knew he couldn't ignore them. He tried to divide the church groups further. He hoped to create a new, moderate group. The Protectorate became like a judge between the two Covenanter groups. This split affected the Scottish church for many years.

The King Returns

After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Scotland got back control of its church. But a new law, the Rescissory Act 1661, undid all the Covenanters' changes from 1638-1639. The Scottish government brought back bishops on September 6, 1661. James Sharp, a leader of the Resolutioners, became Archbishop of St Andrews. Soon, many bishops were appointed.

In 1662, the kirk was restored as the national church. Other religious groups were banned. All public officials had to reject the 1638 Covenant. About a third of the ministers, around 270, refused and lost their jobs. Most of these were in southwest Scotland, where Covenanter support was strong. People continued to hold secret outdoor church meetings, often with thousands attending.

The government sometimes persecuted Covenanters and sometimes tried to be more tolerant. In 1663, dissenting ministers were called "seditious persons." People who didn't go to the official church services faced heavy fines. In 1666, a group of men from Galloway rebelled. They marched on Edinburgh but were defeated at the Battle of Rullion Green. Many were executed or sent away to Barbados.

This rebellion led to a new leader, John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, who tried a softer approach. The government issued "Letters of Indulgence" in 1669, 1672, and 1679. These allowed ministers who had been removed to return to their churches if they stayed out of politics. Some returned, but many refused.

However, persecution returned. Preaching at a secret meeting could be punished by death. Attending one also had severe penalties. In 1678, 3,000 Lowland soldiers and 6,000 Highlanders were sent to Covenanter areas. This was a form of punishment.

Rebellion and "The Killing Time"

In May 1679, Covenanter radicals killed Archbishop Sharp. This led to a revolt that ended at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in June. Many prisoners were taken, and over 1,200 were sentenced to be sent away.

This defeat split the Covenanter movement. The extreme group was led by Donald Cargill and Richard Cameron. In June 1680, they issued the Sanquhar Declaration. This statement said they no longer supported King Charles or his Catholic brother, James. These followers were called Cameronians. Even though they were a small group, the deaths of Cameron and Cargill made them heroes.

In 1681, new laws made it a legal duty to obey the king, no matter his religion. But these laws also confirmed the main status of the kirk. This excluded the Covenanters, who wanted the church to be like it was in 1640. Some government figures disagreed with these laws and refused to swear loyalty.

The Cameronians became more organized as the United Societies. In 1684, they put up copies of an Apologetical Declaration. This was like declaring war on government officers. This led to the period known as "the Killing Time" for Protestants. The Scottish government allowed Covenanters caught with weapons to be killed without a trial.

Despite being Catholic, James VII became king in April 1685. Many people supported him because they feared another civil war. These factors helped quickly defeat Argyll's Rising in June 1685, a rebellion led by Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll.

The Glorious Revolution and New Church Rules

King James VII tried to allow more religious freedom for some Protestants in 1687. But this upset his own supporters, the Episcopalians. At the same time, he excluded the Cameronians. He also created another Covenanter hero when he executed James Renwick in February 1688.

In June 1688, two big events caused a crisis. King James had a Catholic son, which meant his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange would not inherit the throne. Also, James put seven bishops on trial, which seemed like an attack on the Protestant church. When the bishops were found not guilty, James's power was broken. English leaders invited William to become king. James's army left him, and he fled to France.

The Scottish Parliament, called the Scottish Convention, met in March 1689. It was mostly made up of Covenanter supporters. On April 4, it passed the Claim of Right. This said James had lost his right to the crown because of his actions. On May 11, William and Mary became co-monarchs of Scotland. William wanted to keep bishops, but the Covenanters' actions during the Jacobite rising of 1689, like defending Dunkeld, meant their views won.

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland met in November 1690 for the first time since 1654. Before it even met, over 200 Episcopalian ministers had been removed. The Assembly officially got rid of bishops again. Over the next 25 years, almost two-thirds of all ministers were removed. To make up for this, nearly a hundred clergy returned to the church in 1693 and 1695.

After 1690, a small group of Cameronians, led by Robert Hamilton, refused to rejoin the kirk. They continued as a separate group. In 1743, they formed the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland. While this church still exists, most of its members joined the Free Church of Scotland in 1876.

Covenanter Legacy

Memorials and History

Covenanter graves and memorials from "The Killing Time" became very important. They helped keep the Covenanters' story alive. In 1701, their Assembly decided to find and mark the graves of those who died. Many were in remote places because the government had tried to prevent them from becoming places of pilgrimage.

Sir Walter Scott's 1816 novel, Old Mortality, features a character who travels Scotland fixing inscriptions on Covenanter graves. In 1966, the Scottish Covenanter Memorial Association was created. It still looks after these monuments today. One famous monument is at Greyfriars Kirkyard, put up in 1707. It remembers 18,000 people killed between 1661 and 1680.

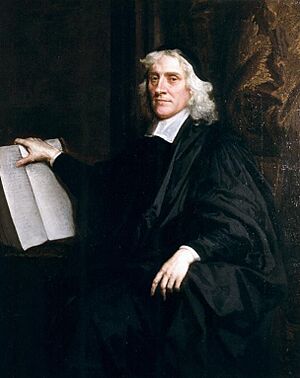

In the early 1700s, Robert Wodrow wrote The History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland from the Restoration to the Revolution. This book described the persecution of the Covenanters from 1660 to 1690. This work was brought up again later when parts of the Church of Scotland felt the government was interfering.

Covenanters in North America

Throughout the 1600s, Covenanter churches were started in Ireland, especially in Ulster. For different reasons, many of these Covenanters later moved to North America. In 1717, William Tennent moved to Philadelphia. He later started Log College, the first Presbyterian seminary (a school for training ministers) in North America.

In North America, many former Covenanters joined the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America. This church was founded in 1743.

Learn More

- Presbyterianism

- Calvinism

- Cameronians

- Reformed Presbyterian Global Alliance

- Solemn League and Covenant

- Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

|

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |