Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

9th Earl of Argyll

|

|

|---|---|

The Earl of Argyll, portrait from Argyll's Lodging.

|

|

| Born | 26 February 1629 |

| Died | 30 June 1685 Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Resting place | Kilmun Parish Church |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow |

| Occupation | Chief of Clan Campbell, military officer, politician |

| Title | 9th Earl of Argyll, member of the Privy Council of Scotland |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll John Campbell of Mamore another two sons and three daughters |

| Parent(s) | Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll Lady Margaret Douglas |

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll (born February 26, 1629 – died June 30, 1685) was an important Scottish noble and soldier. He was the traditional leader, or chief, of Clan Campbell. He played a big role in Scottish politics during a very difficult time in history.

Archibald was a loyal supporter of the King during the later parts of the Scottish Civil War. He even spent time in prison for his beliefs. After King Charles II returned to the throne, Argyll faced problems. This was because he had special legal powers in the Highlands and strong Presbyterian religious views.

In 1681, he was accused of serious wrongdoing and sentenced to death. He managed to escape from prison and went to live in another country. There, he joined groups who were against the King. When King Charles's brother, James, became King in 1685, Argyll returned to Scotland. He tried to remove King James from power, at the same time as another rebellion in England. This attempt, known as Argyll's Rising, failed. Argyll was captured and later executed.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Archibald Campbell was born in 1629 in Dalkeith, Scotland. He was the oldest son of Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, and Lady Margaret Douglas. His grandfather was the Earl of Morton.

When he was four, Archibald was sent to live with a relative, Colin Campbell of Glenorchy. This was a common custom for Scottish noble families back then. His parents made sure he learned both English and Gaelic. He started studying at Glasgow University in 1643. Between 1647 and 1649, his father sent him to travel in France and Italy. This was mainly to keep him safe from the political problems happening in Scotland.

His father was one of the most powerful nobles in Scotland. He became a leader of the Presbyterian Covenanter group. He was almost like the head of the Scottish government for a long time. While Archibald was still traveling, he heard that King Charles I had been executed. He wrote to the Queen, promising his loyalty to the royal family. He also defended his father, but said he would serve the King even against his father if needed. From about 1638, he was known by the special title of Lord Lorne.

Life in the 1650s

In 1650, Lord Lorne returned to Scotland. He married Lady Mary Stuart, the daughter of the Earl of Moray. That same year, he got his first big job. He was appointed to a key government group called the Committee of Estates.

When Charles II came to Scotland in 1650, Lord Lorne was made captain of the King's Foot Guards. He was chosen by the Scottish parliament to protect the King. Charles felt restricted by the strict religious leaders at the time. But Lorne helped him by bringing people he wanted to see. Lorne fought bravely in two important battles: the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 and the Battle of Worcester where Charles was defeated.

Glencairn's Uprising

After the Battle of Worcester, in the winter of 1653, Lord Lorne joined Lord Glencairn. Glencairn was leading a royalist uprising in the Highlands. Lord Lorne's father had tried to make peace with the new government. This caused a disagreement between father and son. Some people thought their differences were faked to protect the family, no matter who won. But Lorne's biographer believed his loyalty to the King was real.

Glencairn's forces faced many problems, including arguments among their leaders. Lorne and another commander almost fought each other. Glencairn also did not fully trust Lorne. At one point, Lorne left his men after a disagreement with Glencairn. Some believed an intercepted letter from Lorne, complaining about Glencairn, was the cause. Others thought the letter suggested a plan to attack Glencairn's own men.

Fighting Against the Commonwealth

In May 1654, the new government offered a general pardon for past actions. But Lord Lorne was one of the few who were not pardoned. In September, he managed to capture a ship carrying supplies for his father's men. Later in 1654, Lorne joined another uprising led by John Middleton. He and his men even raided his father's lands for food. His father had to ask for English soldiers to protect him from his own son.

By December, Lorne was hiding with only a few men. The government thought he might surrender if allowed. But Lorne said he could not give up without Middleton's permission. He was still in touch with King Charles, who thanked him for his loyalty. Even Lorne's wife was forced out of their home by government troops in 1655.

In March 1655, Lorne finally received permission from King Charles to surrender. The King praised Lorne for his efforts in the war. These letters were later used in his trial in 1681 to show his past loyalty to the King. Lorne surrendered in August 1655. He had to promise to stay peaceful and pay a large sum of money.

Even after surrendering, Lorne was watched closely. In January 1656, he again declared his support for King Charles. He even took control of the island of Mull. He later made up with his father, who helped him make new agreements with the English government.

Arrest, Imprisonment, and Head Injury

Despite his agreements, Lorne was still seen with great suspicion. In May 1656, it was reported that he was again in contact with King Charles. As a result, a new oath was demanded from Scottish nobles in 1657. They had to promise to reject the royal family and support the new government. Lorne refused to take this oath and was immediately put in Edinburgh Castle.

While in prison in March 1658, Lorne had a strange accident. He was playing a game similar to bowling. A thrown ball hit a stone and bounced back, hitting Lord Lorne's head. He fell down and was unconscious for hours. He slowly recovered from the skull fracture. Some historians believe this injury might explain some of his later unpredictable behavior and occasional fits of temper. He was likely released from prison in March 1659 or 1660.

After the King's Return

When King Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, Lord Lorne went to London. The King welcomed him kindly. However, his father, the Marquess, was arrested and executed for serious wrongdoing. His family's lands were taken away. Even though Lorne had been loyal to Charles, he had powerful enemies. Fifteen months after his father's death, Lorne himself was threatened with execution. He was accused of "leasing making," which meant spreading lies about the King.

King Charles asked for his sentence to be delayed. Several months later, Lorne was released. In October 1663, he got back his grandfather's title and most of his family's lands. He also became a member of the Royal Society, a group for important scientists and thinkers.

Earl of Argyll

Even though he got his title back, Argyll still had many debts. Some people thought he was too harsh with those who owed him money. They also felt he used his inherited powers unfairly. He was also involved in legal fights with another noble, Montrose, but they later became friends.

In April 1664, Argyll joined the Scottish Privy Council, an important advisory group to the King. He was seen as a key supporter of Lauderdale, another powerful figure.

During the mid-1660s, Argyll mostly stayed at Inveraray Castle. He used his inherited role as the chief judge of the Highlands. He also helped settle disagreements between Highland chiefs. He spent a lot of time planning the gardens at Inveraray, especially planting trees. He wanted the house to look like it was rising out of a thick forest. He also tried to start businesses, like making salt herrings and distilling whisky, hoping to sell them in England.

Argyll was involved in the religious arguments of the time. He helped disarm some Covenanters, a group of strict Presbyterians. But he was seen as a moderate voice on the Privy Council. Some council members, like Archbishop Sharp, were against him. This opposition appeared when the Pentland Rising happened. Sharp did not want Argyll's forces to fight the rebels, fearing Argyll would join them.

In 1667, King Charles II gave Argyll a new official document. This confirmed his ownership of all his lands and his inherited roles. He was also put in charge of keeping order in the Highlands. He remained on good terms with Lauderdale, who was godfather to one of Argyll's children.

In May 1668, Argyll's first wife died. His letters show how sad he was. In October 1669, Lauderdale visited Scotland. Argyll made sure to meet him, even though he knew Lauderdale's future wife was trying to turn him against Argyll. Argyll carried the sceptre at the opening of the Scottish Parliament. This Parliament officially gave back his father's lands and titles.

On January 28, 1670, Argyll married for the second time. His new wife was Lady Anna Mackenzie, a widow. This briefly strained his relationship with Lauderdale.

Argyll did not want to persecute the Covenanters further. But the Privy Council ordered him to stop their religious meetings in his area. In 1674, he became an important judge. He also joined a committee to deal with these meetings. He continued to support moderate actions.

He slowly rebuilt his friendship with Lauderdale. Lauderdale's stepdaughter married Argyll's oldest son. In October 1678, Argyll was given permission to take control of the Isle of Mull. There had been a long dispute over land between Argyll and another clan. It took until 1680 for him to fully control the island.

His Downfall

In April 1679, because of fears about a "Popish Plot" (a false rumor about Catholics), Argyll was ordered to secure the Highlands. He had to disarm all Catholics. He received gunpowder and help from local officials. However, serious unrest broke out among the Covenanters in southern Scotland. They even killed Archbishop Sharp, Argyll's old opponent. Because Argyll had been moderate with the Covenanters, the Privy Council thought about taking away his power. He was ordered to join the King's forces.

By this time, Argyll was in a difficult spot. His Presbyterian beliefs and his father's past made him suspicious to the King's supporters. Also, his special legal powers and strong influence as head of Clan Campbell made him seem like a threat to the King. Things got worse when James, Duke of York, the King's brother, became the main royal representative in Scotland in 1680.

In 1681, a new law called the "Act anent Religion and the Test" was passed. This law required officials to declare their Protestant faith and loyalty to the King. Argyll complained about the law. He pointed out that it seemed to contradict itself. He also worried that the Royal Family, who leaned towards Catholicism, did not have to take it. He hesitated to take the oath himself. When he finally did, he added a condition: "only in as far as it is consistent with itself." Argyll believed this was acceptable to the Duke of York.

But this condition was enough for an angry James, supported by Argyll's enemies. On November 9, he was arrested. He was accused of serious crimes, including trying to take legislative power, lying under oath, and "leasing making" (spreading lies about the King).

Argyll's trial began on December 12, 1681. The jury was mostly made up of his enemies. Argyll refused to defend himself. The jury found him guilty of some charges. People in both England and Scotland were very upset by how Argyll was treated. Many blamed the Duke of York. A famous politician said that in England, they wouldn't "hang a dog" on such weak evidence. It was said that the King and James only wanted to humble Argyll and take away his powers, not execute him. The King ordered that a death sentence be announced but not carried out right away. However, Argyll did not trust James. He escaped from prison.

On December 22, the King's letter arrived. The next day, a death sentence and the loss of his lands were announced, even though Argyll was not there. His lands were taken, and his special legal powers were given to another noble.

Escape and Exile

At the end of 1681, Argyll was in Edinburgh Castle, expecting to die soon. But on December 20, his stepdaughter, Sophia Lindsay, got permission to visit him. She brought a countryman dressed as a page, with his head wrapped up as if he had been in a fight. Argyll and the countryman swapped clothes. The trick worked!

Lindsay left the castle crying, with Argyll disguised as her page. Some guards almost noticed, but they were distracted. At the gate, Argyll quietly slipped away behind the coach. He went to a friend's house, who helped him travel to London under a false name.

In London, Argyll was hidden by friends. He even found refuge with a man who had arrested him years before. No real effort was made to recapture him. It was even said that King Charles II knew where he was but chose not to arrest him. This was probably because arresting such a well-known Protestant would have been very unpopular.

During this time, Argyll started meeting with people who were against the King. He became a key figure in secret groups of Whigs. In late 1682, the government learned he was involved in rebellious activities. Efforts to find him increased, and he fled to Holland, where many other opponents of the King were gathering.

Involvement in the Rye House Plot

In June 1683, some people were arrested after the discovery of the Rye House plot. This was a plan to assassinate King Charles and his brother. Letters from Argyll, written in code, were found among their papers. Argyll's private secretary helped to decode them. The letters showed that Argyll had discussed a plan for an uprising in Scotland. He asked for money and soldiers from other plotters. He said he could gather many men in Scotland if he had the resources.

One of Argyll's contacts was arrested and questioned. This showed that Argyll was in London at the time. Later, Argyll's family papers were found hidden in Scotland.

The "Argyll Expedition"

Planning the Invasion

While in Holland, Argyll became friends with the Duke of Monmouth. When King Charles II died and James VII became King, Argyll moved to Rotterdam. In April 1685, he attended a meeting where they decided to invade Scotland right away. Argyll worked hard to convince Monmouth that a joint invasion was possible. He claimed he could gather many men from his lands in Scotland. He also insisted that Monmouth should promise not to declare himself King.

Argyll paid for the invasion preparations with money from supporters. He sailed from Holland on May 1 or 2, 1685. He had about 300 men on three small ships. Other Scottish exiles joined him. Two English plotters also went with Argyll. Monmouth had promised to start his own rebellion, the Monmouth Rebellion, within a few days. But he actually sailed several weeks later.

Landing in Scotland

The expedition faced bad luck and disagreements among its leaders. They stopped near Orkney on May 6. One of Argyll's men went ashore but was arrested. This alerted the authorities to the invasion. Argyll sailed towards his homeland but was forced by bad winds to go to the Sound of Mull. He was delayed there for three days. Then, with 300 men he gathered, he went to Kintyre, an area known for Covenanter support.

At Campbeltown, Argyll issued a statement. He claimed King James had caused King Charles's death and that Monmouth was the rightful heir. He also said he had been given back his title and lands by Monmouth. He had sent his son to gather his former tenants. But very few answered his call.

The rebels marched to Tarbert. There, Argyll issued a second statement. He denied that he was seeking personal gain. He promised to pay his father's debts and his own. He hoped for widespread support from Covenanters. But many of the stricter Presbyterians were angry because Argyll had been involved in the trial of one of their leaders. Most of the men who joined the rebellion were from Clan Campbell. The government had also placed many soldiers in areas likely to support Argyll.

At Tarbert, Sir Duncan Campbell joined Argyll with a large group of men. The leaders decided to invade Lowland Scotland. But Argyll disagreed. He was delayed at Bute for three days. His forces then marched to Cowal in Argyllshire. After a pointless raid on Greenock, he moved to Inveraray. But when two English warships appeared, he had to hide his ships. He captured Ardkinglass castle but gave up on taking Inveraray. He then returned to his hiding place. He wanted to attack the warships, but his men refused. His soldiers deserted, and the King's ships captured Argyll's ships, cannons, and supplies. They also took Argyll's flag, which said: "For God and Religion, against Popery, Tyranny, Arbitrary Government, and Erastianism."

Attempted Invasion of the Lowlands

In a bad situation, Argyll decided to try invading the Lowlands. Near Dumbarton, he set up camp in a good position facing the King's troops. But his plan to fight was rejected. The rebels retreated towards Glasgow without a battle. They crossed the River Clyde at Renfrew. His army shrank from two thousand to five hundred men. After a few small fights, Argyll found himself alone with his son John and three friends. To avoid being caught, they split up. Only Major Fullarton stayed with Argyll.

They were refused shelter at an old servant's house. The two crossed the Clyde to Inchinnan. On June 18, a group of local soldiers found them. Argyll was said to have tried to fire his pistols, but the gunpowder was wet. One of his captors, a weaver, hit him over the head. Argyll was heavily disguised with a countryman's hat and a full beard. It was said (though probably not true) that he was only recognized when he cried, "Alas, unfortunate Argyll!" as he fell. The soldiers supposedly cried when they realized who they had captured, but they still handed him over to the authorities.

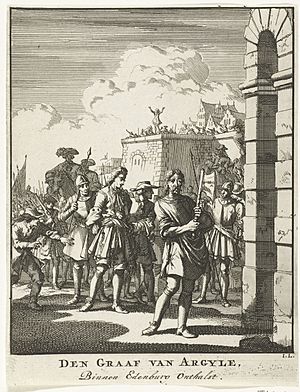

He was taken first to Renfrew and then to Glasgow. On June 20, he arrived in Edinburgh. He was taken to the castle and put in chains. He was questioned about his friends and threatened with torture. While in prison, his sister and wife visited him. His wife and Sophia Lindsay had also been imprisoned when news of his landing arrived.

Death

On June 30, 1685, Argyll was executed in Edinburgh, just like his father. He had spent a lot of time in Holland preparing for the death he expected. He faced his execution with courage and even humor. A story was later told that an official who came to take him to his execution found him sleeping peacefully. The official felt bad seeing Argyll's calmness. (However, some said that after his 1658 head injury, he always took a similar nap every day.)

He wrote to Sophia Lindsay: "what shall I say in this great day of the Lord, wherein, in the midst of a cloud, I find a fair sunshine. I can wish no more for you, but that the Lord may comfort you, and shine upon you as he doth upon me, and give you that same sense of His love in staying in the world, as I have in going out of it." On the scaffold, he gave a speech. He repeated his opposition to "Popery" (Catholicism). Finally, he joked that the guillotine, which was his "inlet to glory" (way to heaven), was "the sweetest maiden he had ever kissed."

He was first buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard. Later, his body was moved to Kilmun Parish Church.

Character

There are not many personal descriptions of Argyll. The strong political differences of his time led to very different opinions of him. One writer said he was "witty in knacks" (clever with small inventions) and had about twenty pockets in his clothes. Another said he had habits of winking and holding his thumb in his palm, which were thought to be bad signs. Argyll himself mentioned his small size.

Some historians who supported the King wrote negative stories about Argyll. One quoted a noble who said Argyll's looks and way of talking were not appealing. However, Argyll, like his father, had many enemies. Other sources give a much more positive view of him. One historian noted that Argyll's letters about his first wife's death were "touching." Another wrote that his private letters showed him to be a "man of singularly affectionate character and tender heart." They added that his behavior at his execution showed great personal bravery.

Family

On May 13, 1650, at the Canongate Kirk, he married Lady Mary Stewart. She was the daughter of the 4th Earl of Moray. They had seven children:

- Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll

- John Campbell of Mamore, a member of the Scottish Parliament; father of John Campbell, 4th Duke of Argyll

- Charles Campbell, a member of Parliament for Campbeltown

- James Campbell (born around 1660 – died around 1713)

- Mary Campbell

- Anne Campbell, who married twice

- Jean Campbell, who married William Kerr, 2nd Marquess of Lothian

He married again in 1670 to the widow Lady Anne Mackenzie, Countess of Balcarres. She outlived her husband and died of old age in 1707.

See Also

Images for kids

-

The Earl of Argyll, portrait from Argyll's Lodging.

-

Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, with his second wife Anna.

-

The Last Sleep of Argyle, Victorian history painting by Edward Matthew Ward, based on Robert Wodrow's story of Argyll being found sleeping soundly by an official bringing him for execution.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |