Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

A riot started by Jenny Geddes because King Charles I wanted to use a new prayer book in Scotland. This peaceful protest soon turned into armed fighting. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| Fluctuating, 2,000–4,000 troops at any one time | Over 30,000 troops, but many based in England and Ireland | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Total of 28,000 battlefield deaths on both sides, more soldiers die from disease, c. 45,000 civilian deaths, both from disease and deliberate targeting | ||||||||

From 1639 to 1652, Scotland was part of a big conflict called the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. This series of wars included fights between Scotland and England, a rebellion in Ireland, and the English Civil War. In the end, England's army, led by Oliver Cromwell, took control of both Ireland and Scotland.

Within Scotland, a civil war happened from 1644 to 1645. It was fought between Scottish Royalists, who supported King Charles I, and the Covenanters. The Covenanters had been in charge of Scotland since 1639. They were also friends with the English Parliament. The Scottish Royalists, helped by Irish soldiers, won many battles in 1644–45. But the Covenanters eventually defeated them.

After this, the Covenanters disagreed with the English Parliament. So, they crowned Charles II as their king. They wanted him to rule England and Ireland too. This led to another war (1650–1652). England's army, led by Oliver Cromwell, invaded and took over Scotland.

Contents

- Why the Wars Started in Scotland

- Scottish Royalists and Covenanters: Who Fought Whom?

- Irish Soldiers Join the Fight

- Royalist Victories and Defeat

- The End of the Scottish Civil War

- Scotland and the Second English Civil War

- England Invades Scotland (1650–1652)

- From English Control to the King's Return

- The Cost of the Wars

- Timeline of Events

- Images for kids

Why the Wars Started in Scotland

The main reason for the war in Scotland was that King Charles I wanted to change the Scottish church, known as the Kirk. He tried to make it more like the Church of England. In February 1638, many Scots signed the National Covenant. This was a promise to resist the King's changes.

The Covenanters believed they were protecting their religion. They also felt Scotland was being ignored since the Scottish kings became kings of England in 1603. The Kirk was a symbol of Scotland's independence.

Scotland won the Bishops' Wars against England in 1639 and 1640. This put the Covenanters in charge of Scotland. But it also caused problems in Ireland and England. The English Parliament refused to give King Charles money for a war against Scotland. So, Charles thought about getting an army from Irish Catholics. This worried his enemies in England and Scotland.

When the Covenanters threatened to help Protestants in Ireland, it sparked the Irish Rebellion of 1641. This rebellion quickly led to many Protestants being killed in Ireland.

In April 1642, the Covenanters sent an army to Ireland. This army also carried out bloody attacks against Catholics. Both King Charles and the English Parliament wanted to stop the Irish rebellion. But they didn't trust each other. This fight for control of the army eventually led to the First English Civil War in August 1642.

Scottish Royalists and Covenanters: Who Fought Whom?

The Scottish Reformation made the Kirk a Presbyterian church. By 1640, only a small number of Scots were Catholic. But many Scots still feared "Popery" (Catholicism). Covenanters believed a king was part of God's plan. So, they promised to "defend the king's person and authority." They couldn't imagine a country without a king.

This meant that unlike in England, all Scots agreed that having a king was right. The Covenanters even supported bringing Charles I back to power. Later, they supported his son, Charles II. The main disagreement was about how much power the King should have compared to the people. This included the power of the Presbyterian church, which was run by the people.

Royalist support was strongest in the Scottish Highlands and Aberdeenshire. This was for religious, cultural, and political reasons. Montrose, a key Royalist leader, switched sides because he didn't trust the Covenanter leader Argyll. He feared Argyll wanted too much power.

The Highlands were also different culturally and politically. People there spoke Gaelic. Many Highland clans preferred the King's distant rule to the powerful Covenanter government in the Lowlands.

Family rivalries also played a part. The Presbyterian Clan Campbell, led by Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll, sided with the Covenanters. So, their rivals often joined the Royalists. For example, the MacDonalds were Catholic and enemies of the Campbells. They also had a strong Gaelic identity, like many Irish people.

Irish Soldiers Join the Fight

By 1644, Montrose had tried and failed to start a Royalist uprising. Then, the Irish Confederates, who were loosely allied with the Royalists, agreed to send soldiers to Scotland. They hoped this would keep Scottish Covenanter troops busy in Scotland.

The Irish sent 1,500 men to Scotland. They were led by Alasdair MacColla MacDonald, a MacDonald clansman from Scotland. This group included Manus O'Cahan and his 500-man Irish regiment. After landing, the Irish joined Montrose. They also gathered more fighters from the MacDonalds and other Highland clans who were against the Campbells.

This new Royalist army was very strong. Its Irish and Highland soldiers could move very quickly. They marched long distances, even over rough Highland land. They could also handle tough conditions and little food. They didn't fight in tight formations like other armies. Instead, they fired their muskets loosely, then attacked with swords. This worked well in the Highlands. It often scared away the poorly trained Covenanter militias. These local soldiers would often run away and be killed.

However, the Royalist army had big problems. The clans from western Scotland often wouldn't fight far from home. They saw the Campbells as their main enemy, not the Covenanters. This meant the army's size changed a lot. The Royalists also didn't have many cavalry (horse soldiers). This made them weak in open areas. Montrose used his leadership and the mountains to overcome some of these issues. He kept his enemies guessing where he would strike next. He would attack towns in the lowlands, then retreat to the Highlands when a bigger enemy force appeared.

Royalist Victories and Defeat

From 1644 to 1645, Montrose led the Royalists to six famous victories. He defeated Covenanter armies that were larger than his own force of about 2,000 men.

In autumn 1644, the Royalists marched to Perth. They crushed a Covenanter force at the Battle of Tippermuir on September 1. Soon after, another Covenanter militia was defeated outside Aberdeen on September 13. Montrose unwisely let his men steal from Perth and Aberdeen. This made people in those areas, who had supported the Royalists, turn against them.

After these wins, MacColla wanted to continue the MacDonalds' fight against the Campbells in Argyll. In December 1644, the Royalists attacked the Campbells' land. They burned Inveraray and killed about 900 armed Campbells.

In response, Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll gathered his Campbell clansmen. Montrose found himself trapped. He was between Argyll's forces and Covenanters coming from Inverness. So, Montrose marched through the snowy mountains of Lochaber. He surprised Argyll at the Battle of Inverlochy on February 2, 1645. The Covenanters and Campbells were crushed, losing 1,500 men.

Montrose's march was called "one of the great exploits" in British history. The victory at Inverlochy gave the Royalists control of the western Highlands. It also brought more clans and nobles to their side. The most important were the Gordons, who gave the Royalists cavalry for the first time.

Inverlochy was a very important win. The Scottish Covenanter army in England had to send some of their soldiers back north. This made the Scottish army in England much weaker.

In April, Montrose was surprised by General William Baillie near Dundee. But Montrose escaped by having his troops quickly turn back and flee inland. Another Covenanter army was quickly put together. At Auldearn, Montrose tricked the enemy. He placed most of his foot soldiers where the enemy could see them. He hid his cavalry and other foot soldiers. The trick worked, and the Covenanters were defeated on May 9.

Another chase between Baillie and Montrose led to the Battle of Alford on July 2. Montrose attacked the Covenanters after they crossed the River Don. This forced them to fight with the river behind them. The Royalists won and moved into the lowlands. Baillie chased them, and Montrose waited at Kilsyth. During the battle, the Royalists won a great victory.

After Kilsyth (August 15), Montrose seemed to control all of Scotland. Towns like Dundee and Glasgow fell to his forces. The Covenanter government had fallen apart. Montrose wanted to raise more troops and march on England. But MacColla wanted to continue the MacDonalds' war against the Campbells. The Gordons also went home to protect their own lands.

Montrose had not been able to get many lowland Royalists to join him. Even after Kilsyth, few joined. They didn't like his use of Irish Catholic troops, who were seen as "barbarians." Also, his past as a Covenanter made some Royalists distrust him.

Montrose's forces split up. He was then surprised and defeated by the Covenanters, led by David Leslie, at the Battle of Philiphaugh. About 100 Irish prisoners were killed after they surrendered. Around 300 of the Royalist army's camp followers, mostly women and children, were also killed. MacColla retreated and held out until the next year. In September 1646, Montrose fled to Norway. The Royalist victories in Scotland disappeared almost overnight because their forces were not united.

The End of the Scottish Civil War

The First English Civil War ended in May 1646. King Charles I surrendered to the Scottish Covenanter army in England. The Scots tried to get the King to agree to their Covenant. When he refused, they handed him over to the English Parliament in early 1647. They also received some payment for their army's service in England.

In 1646, Montrose left for Norway. MacColla returned to Ireland with his remaining Irish and Highland soldiers. Those who had fought for Montrose were often killed by the Covenanters when captured. This was revenge for the attacks the Royalists had done in Argyll.

Scotland and the Second English Civil War

It's interesting that after defeating the Royalists at home, the Covenanters then talked with Charles I against the English Parliament. The Covenanters couldn't agree with their former friends on how to settle the wars. They wanted Presbyterianism to be the official religion in all three kingdoms. They also feared that the English Parliament would threaten Scottish independence. Many Covenanters worried that Scotland would become just a "province of England."

A group of Covenanters called the Engagers, led by the Duke of Hamilton, sent an army to England. They tried to bring Charles I back to power in 1648. But Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army crushed them at the Battle of Preston. This action for the King caused a short civil war among the Covenanters themselves. The most strict Presbyterians, led by the Earl of Argyll, rebelled against the main Scottish army. They fought at the Battle of Stirling in September 1648, before a quick peace was made.

Charles I was executed by the English Parliament in 1649. Hamilton, who was captured after Preston, was also executed. This left the extreme Covenanters, still led by Argyll, as the main power in Scotland.

Montrose's Final Defeat

In June 1649, Montrose was made lieutenant of Scotland again by the exiled Charles II. Charles also started talking with the Covenanters, who were now led by Argyll's strict Presbyterian group. Montrose had little support in the lowlands. So Charles was willing to give up his most loyal supporter to become king on the Covenanters' terms.

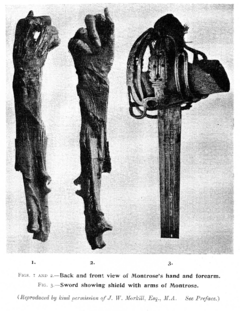

In March 1650, Montrose landed in Orkney to lead a small force of hired soldiers. He tried to get the clans to join him, but failed. On April 27, he was surprised and defeated at the Battle of Carbisdale. After wandering for a while, he was captured. He was brought to Edinburgh and sentenced to death on May 20. He was hanged on May 21. Until the end, he said he was a true Covenanter and a loyal subject.

England Invades Scotland (1650–1652)

Even though they fought the Scottish Royalists, the Covenanters then supported Charles II. They signed the Treaty of Breda (1650) with him. They hoped to keep Scotland independent and Presbyterian, free from English Parliament's control. Charles landed in Scotland on June 23, 1650. He immediately signed the 1638 Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League.

The new English Republic saw Charles II and his Covenanter allies as a big threat. So, Oliver Cromwell left some of his officers in Ireland to finish defeating the Irish Royalists. He returned to England in May. He arrived in Scotland on July 22, 1650, moving along the east coast towards Edinburgh. By late August, his army was sick and running out of supplies. He had to retreat to his base at Dunbar.

A Scottish Covenanter army, led by David Leslie, had been following Cromwell. Leslie saw some of Cromwell's sick troops getting on ships. He thought Cromwell's army was weak. Cromwell saw his chance. His New Model Army completely defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar on September 3. Leslie's army was destroyed. They lost over 14,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. Cromwell's army then took Edinburgh. By the end of the year, his army controlled much of southern Scotland.

This military disaster made the strict Covenanters look bad. It caused the Covenanters and Scottish Royalists to put aside their differences. They tried to push back the English invasion. The Scottish Parliament ordered every town and area to raise soldiers in December 1650. A new round of conscription happened in both the Highlands and Lowlands. This formed a truly national army, led by Charles II himself. This was the largest army the Scots put together during the wars. But it was poorly trained and had low morale. Many of its Royalist and Covenanter parts had been fighting each other until recently.

In July 1651, part of Cromwell's army crossed into Fife. They defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing. The New Model Army moved towards the royal base at Perth. Charles ordered his army south into England. This was a desperate attempt to avoid Cromwell and start a Royalist uprising there. Cromwell followed Charles into England. He left George Monck to finish the campaign in Scotland. Monck took Stirling on August 14 and Dundee on September 1. He reportedly killed up to 2,000 people and destroyed all 60 ships in the city's harbor.

The Scottish Army marched west into England. They hoped to find strong English Royalist support there. However, fewer English Royalists joined than Charles had hoped. Cromwell finally fought the new king at Worcester on September 3, 1651. He defeated Charles's army, killing 3,000 and taking 10,000 prisoners. Many Scottish prisoners were sold into forced labor in the West Indies and Virginia. This defeat marked the real end of Scotland's war effort. Charles escaped to Europe. With his flight, the Covenanters' hopes for political independence from England were gone.

From English Control to the King's Return

Between 1651 and 1654, Royalists in Scotland rebelled. Dunnottar Castle was the last place to fall to the English army in May 1652. Under the Tender of Union, Scots were given 30 seats in a united Parliament in London. General Monck was made the military governor of Scotland. During this time, Scotland was controlled by an English army led by George Monck.

Small Royalist rebellions continued in Scotland, especially in the western Highlands. Monck built forts across the Highlands. He ended Royalist resistance by sending prisoners to the West Indies as forced laborers. However, crime remained a problem. Bandits, often former soldiers, robbed both English troops and civilians.

After Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, the different groups in England started fighting for power again. Monck, who had served Cromwell, decided it was best to bring back Charles II as king. In 1660, he marched his troops south from Scotland to make sure the king was restored. Scotland's Parliament and its own laws were brought back. But many issues that caused the wars, like religion and how Scotland was governed, were not solved. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, many more Scots would die over these same disagreements in later rebellions.

The Cost of the Wars

It's thought that about 28,000 men were killed in battles in Scotland during these wars. More soldiers usually died from disease than in fighting. So, the true number of military deaths is likely higher. Also, about 15,000 civilians died directly from the war, either from killings or disease.

Another 30,000 people died from the plague in Scotland between 1645 and 1649. This disease was partly spread by armies moving around the country. If we add the thousands of Scottish soldiers who died in the civil wars in England and Ireland (at least 20,000 more), the Wars of the Three Kingdoms were one of the bloodiest times in Scottish history.

Timeline of Events

This timeline shows the main events and who was in charge in Scotland.

Scottish Groups in the Wars

- Royalists: Supported King Charles I and the Church of England.

- Covenanters: Signed the National Covenant and fought against Charles I.

- Engagers: A group of Covenanters who later fought for Charles I.

- Kirk Party: Covenanters who fought against Charles I until he was executed.

- Resolutioners: Kirk Party Covenanters who then supported Charles II.

- Protesters: Kirk Party Covenanters who fought for the English Parliament against Charles II.

| Period | Years | Royalists | Covenanters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagers (Royalists) |

Kirk Party | ||||

| Resolutioners | Protesters | ||||

| Union of the Crowns | 1603–1639 | pro-King | anti-King | ||

| Bishops' Wars | 1639–1640 | pro-King | anti-King | ||

| 1st English Civil War | 1642–1646 | pro-King | anti-King | ||

| 2nd English Civil War | |||||

| 1648 | pro-King | anti-King | |||

| Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652) | 1650–1651 | pro-King | pro-King | anti-King | |

| Interregnum | 1651–1660 | pro-King | anti-King | ||

| Restoration | 1660–1661 | pro-King | anti-King | ||

| 1661–1689 | pro-King | anti-King | |||

Key Dates in Scotland's Wars

| Date | Event | Effect | Dominant Scottish Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Wars | |||

| 1603 March 24 | Union of the Crowns | James VI and I became King of England and Scotland | Royalists |

| 1625 March 27 | Charles I became King | ||

| 1637 | New Prayer Book forced on Scottish church | Started riots | |

| 1638 February 28 | National Covenant signed | The Kirk rejected the Church of England's control | Covenanters |

| First Bishops' War (1639) | |||

| 1639 June 19 | Treaty of Berwick | Charles I gave in to Covenanters. End of First Bishops' War | |

| Second Bishops' War (1640) | |||

| 1640 August 28 | Battle of Newburn | Big Covenanter victory | |

| 1640 October 26 | Treaty of Ripon | Charles I had to pay for the Scottish army | |

| 1641 August 10 | Treaty of London | Charles I gave in to Covenanters. End of Bishops' Wars | |

| First English Civil War (1642–1646) | |||

| 1643 September 25 | Solemn League and Covenant | English Parliament and Covenanters became allies | Kirk Party |

| Scottish Civil War (1644–1645) | |||

| 1644 September 1 | Battle of Tippermuir | Victory for Royalists | |

| 1645 February 2 | Battle of Inverlochy | Royalist victory | |

| 1645 August 15 | Battle of Kilsyth | Royalists seemed to win control of Scotland | Engagers |

| 1645 September 13 | Battle of Philiphaugh | Covenanter army returned and defeated Royalists | Kirk Party |

| 1646 May 5 | Charles I surrendered to Covenanters | End of First English Civil War and Scottish Civil War | |

| Second English Civil War (1648) | |||

| 1647 December 26 | Charles I agreed to the Engagement | Many Covenanters refused to fight for the King | Engagers |

| 1648 August 17 | Battle of Preston | Cromwell's army defeated the Engagers | |

| 1648 September 27 | Treaty of Stirling | Engagers left the government | Kirk Party |

| 1649 January 30 | Charles I executed in London | Many Scots were horrified. End of Second English Civil War | |

| 1649 February 5 | Scots declared Charles II as King | Kirk Party sided with Charles II | Resolutioners |

| 1650 May 1 | Treaty of Breda | Charles II agreed to Covenanter terms | |

| 1650 June 23 | Charles II signed Solemn League and Covenant | ||

| Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652) | |||

| 1650 September 3 | Battle of Dunbar | Major English victory over the Scots | |

| 1651 January 1 | Charles II crowned by Resolutioners | Raised a new army | |

| 1651 September 3 | Battle of Worcester | Decisive English victory. End of English Civil Wars | Protesters |

| English Occupation (1651–1660) | |||

| 1651 October 28 | Tender of Union | Scottish Parliament ended, Scots given seats in English Parliament | |

| 1653 August | Start of Royalist uprising | ||

| 1654 May 5 | Act of Pardon and Grace | Cromwell pardoned many Royalists | |

| 1654 July 19 | Battle of Dalnaspidal | End of Royalist uprising | |

| King Returns (1660–1689) | |||

| 1660 May 14 | Charles II proclaimed king in Edinburgh | Resolutioners | |

| 1661 March 28 | Rescissory Act | Ended all Parliament acts since 1633 | |

| 1662 | Church leaders had to reject the Covenant | Royalists | |

Images for kids