Execution of Charles I facts for kids

The execution of King Charles I by beheading happened on Tuesday, January 30, 1649. It took place outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London. This event was the final act in a big fight between the King's supporters, called Royalists, and the Parliament's supporters, known as Parliamentarians. This fight was the English Civil War.

King Charles I was the ruler of England, Scotland, and Ireland. After the war, he was captured and put on trial. On January 27, 1649, a special court set up by Parliament, called the High Court of Justice, found Charles guilty. They said he tried to have "unlimited and tyrannical power" and wanted to "overthrow the rights and liberties of the people." Because of this, he was sentenced to death by beheading.

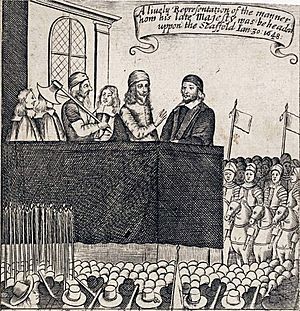

Charles spent his last days at St James's Palace. His loyal friends and family visited him. On January 30, he was taken to a large black scaffold built in front of the Banqueting House. A huge crowd gathered to watch the King's execution. Charles stepped onto the scaffold and gave his last speech. He said he was innocent of the crimes Parliament accused him of. He also called himself a "martyr of the people." The crowd could not hear him well because many Parliamentarian guards blocked the view. But Charles's friend, Bishop William Juxon, wrote down his speech. Charles said a few last words to Juxon, speaking of his "incorruptible crown" in Heaven. Then, he put his head on the block. After a moment, he gave a signal, and the executioner beheaded him with one swift blow. The executioner silently held up Charles's head to the crowd.

Many people say this execution was one of the most important and debated events in English history. Some people saw it as the sacrifice of an innocent man. For example, a historian named Edward Hyde called it "a year of reproach and infamy." Others saw it as a key step towards democracy in Britain. John Cook, who was the prosecutor for Charles I, said the execution was a sentence "not only against one tyrant but against tyranny itself."

Contents

The Execution Day

The execution was planned for January 30, 1649. On January 28, the King was moved from the Palace of Whitehall to St James's Palace. This was probably to avoid the noise of the scaffold being built. Charles spent that day praying with the Bishop of London, William Juxon.

On January 29, Charles burned his private papers. He had not seen his children for 15 months. So, Parliament allowed him to speak to his two youngest children one last time. These were Elizabeth, who was 14, and Henry, who was 10. He told Elizabeth to stay true to her "Protestant religion." He also asked her to tell her mother that his thoughts were always with her. He told Henry not to let Parliament make him a "puppet king." Many people thought Parliament might try to make Henry King. Charles gave his jewels to his children. He only kept his George, which was a small figure of St. George. Charles had a restless last night and only fell asleep at 2 a.m.

Charles woke up early on the day of his execution. He started dressing at 5 a.m. He put on fine black clothes and his blue Garter sash. His preparations lasted until dawn. He told his attendant, Thomas Herbert, what to do with his few remaining things. He asked for an extra shirt. He did not want the crowd to see him shiver from the cold and think he was scared. Before leaving, Juxon gave Charles the Blessed Sacrament. This was so Charles would not faint from hunger on the scaffold. At 10 a.m., Colonel Francis Hacker told Charles it was time to go to Whitehall for his execution. At noon, Charles drank a glass of wine and ate some bread.

A large crowd had gathered outside the Banqueting House. The platform for Charles's execution was set up there. The platform was covered in black cloth. Staples were put into the wood for ropes, in case Charles needed to be held down. The execution block was very low. The King would have had to lie down to place his head on it. This was a very submissive pose. The executioners wore masks and wigs to hide their identities.

Just before 2 p.m., Colonel Hacker called Charles to the scaffold. Charles came through a window of the Banqueting Hall. Herbert called it "the saddest sight England ever saw." Charles saw the crowd. He realized the guards would stop them from hearing his speech. So, he spoke to Juxon and Matthew Thomlinson, one of the judges. Juxon wrote down the speech. Charles said he was innocent of the crimes Parliament accused him of. He also said he was faithful to Christianity. He claimed Parliament had caused all the wars. He called himself "a martyr of the people." He said he would be killed for their rights.

Charles asked Juxon for his silk nightcap to put on. This was so the executioner would not be bothered by his hair. He turned to Juxon and said he "would go from a corruptible crown to an incorruptible crown." He meant he believed he would go to Heaven. Charles gave Juxon his George, sash, and cloak. He said one mysterious word: "remember." Charles laid his neck on the block. He asked the executioner to wait for his signal. A moment passed, and Charles gave the signal. The executioner beheaded him with one clean blow.

The executioner silently held up Charles's head to the people watching. He did not shout the usual words, "Behold the head of a traitor!" This might have been because he was new to public executions or feared being recognized. A Royalist named Philip Henry said the crowd let out a loud groan. He wrote that he had "never heard before and I desire I may never hear again." However, other accounts from that time do not mention this groan. The executioner dropped the King's head into the crowd. Soldiers rushed around it, dipping their handkerchiefs in his blood. They also cut off pieces of his hair. The body was then put in a coffin covered with black velvet. It was placed temporarily in the King's old room in Whitehall.

Who Was the Executioner?

The people who executed King Charles I wore masks and wigs. Their identities were never officially revealed to the public. Only Oliver Cromwell and a few close friends likely knew who they were. The clean cut on Charles's head showed the executioner was skilled with an axe. But the fact he didn't shout "Behold the head of a traitor!" might mean he was not used to public executions. Or, he might have been afraid of being identified by his voice.

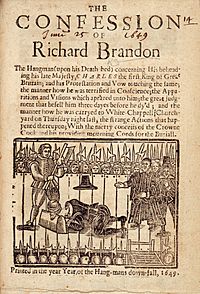

Many people wondered who the executioner was. Different names appeared in newspapers at the time. These included Richard Brandon, William Hulet, and others. Some of these were just rumors.

Colonel John Hewson was in charge of finding an executioner. He offered 40 soldiers £100 and a quick promotion for the job. No one came forward right away. It is thought that one of these soldiers later took the job. William Hulet is a likely candidate. He received a quick promotion after the execution. He was also not seen at the execution that day. Hulet said he was in prison that day for refusing the job. But his promotion soon after makes this seem unlikely. William Hulet was tried as the executioner in October 1660. He was sentenced to death. But this sentence was later overturned when new evidence was found.

The most likely person to be the executioner was Richard Brandon. He was the common hangman at the time. He was experienced, which explains the clean cut. He also reportedly received £30 around the time of the execution. Brandon had executed other Royalists before and after Charles. Despite this, Brandon always denied being the executioner. A letter from that time says he refused an offer of £200 from Parliament to do the job. A pamphlet published after Brandon's death, called The Confession of Richard Brandon, claimed he confessed on his deathbed. But this pamphlet is now thought to be a fake.

Reactions to the Execution

In Britain

On the day of his execution, Charles's actions were seen as fitting for a martyr. A biographer named Geoffrey Robertson said Charles "played the martyr's part almost to perfection." This was not by chance. Royalist reports made the crowd's horror seem greater. They also stressed Charles's innocence. Charles himself seemed to plan for his future as a martyr. He was reportedly happy that the Bible passage read that day was Matthew 27. This chapter tells the story of the Crucifixion.

A book called Eikon Basilike began to spread in England right after Charles was executed. This book was supposedly Charles's own thoughts and life story. It became very popular, with twenty editions printed in the first month. It showed Charles as a religious "martyr of the people." This made Royalists even more passionate. Some parts of the book were even turned into songs for people who could not read. John Milton called it "the chief strength" of the Royalist cause.

Parliamentarians fought back with their own messages. They stopped Royalist books like the Eikon Basilike from being printed. They arrested the printers of such books. At the same time, they worked with publishers to print books that supported the execution. They printed twice as many books as their opponents in February after Charles's death. They even asked Milton to write Eikonoklastes. This book made fun of the Eikon Basilike and its supporters. Charles's prosecutor, John Cook, wrote a pamphlet defending the execution. He said it "pronounced sentence not only against one tyrant but against tyranny itself." These writings made people feel safe about the execution. Even though killing a king went against how society was supposed to work, the people who executed Charles felt secure.

In Europe

Most European leaders were shocked and upset by the King's execution. But very little was done against the new English government. Other countries avoided cutting off ties with England. Even allies of the Royalists, like the Vatican, France, and the Netherlands, did not want to harm their relationships with England. Most European nations had their own problems to deal with. So, the execution was treated with "half-hearted irrelevance." As historian C. V. Wedgwood said, European leaders mostly just said they were upset. But they acted based on what was practical.

One big exception was the Russian Tsar Alexis. He stopped all diplomatic relations with England. He also welcomed Royalist refugees in Moscow. He banned all English merchants from his country. He even sent money to Charles II and condolences to Henrietta Maria, Charles I's wife.

In the American Colonies

News of Charles I's execution traveled slowly to the colonies. On May 26, Roger Williams of Rhode Island reported that "the King and many great Lords and Parliament men are beheaded." On June 3, Adam Winthrop in Boston reported that a ship from London brought news that "the King is beheaded."

Legacy of the Execution

The image of Charles's execution was very important to the idea of St. Charles the Martyr. This was a big part of English Royalism at the time. Soon after Charles's death, people claimed that items from his execution performed miracles. For example, handkerchiefs with Charles's blood supposedly cured a disease called the King's Evil. Many poems and religious works were created to praise Charles and his cause.

After the English monarchy was brought back in 1660, this private worship became official. In 1661, the Church of England declared January 30 a special day of fasting. It was to remember Charles's martyrdom. Charles was seen as a saint in prayer books. During Charles II's reign, about 3,000 sermons were given each year to remember Charles I's death. Many histories written after the monarchy returned showed the execution as a grand and sad play. They described Charles's last days in a very positive way, almost like a saint's life. Few people saw the executed king as having any faults.

After the Glorious Revolution, the idea of Charles as a martyr continued. Even as Royalism became less popular, the anniversaries of Charles's execution still brought out Royalist support. Early historians who supported Parliament, like James Wellwood, still criticized the execution. To make the cult of Charles less powerful, later Whig historians said Charles was a tyrant. They saw his execution as a step towards a government with a constitution in Britain.

However, by the Victorian era, the view of the Whig historians became more common. The Church of England officially removed January 30 as a day to remember Charles's "martyrdom" in 1859. The number of sermons about Charles I's death also decreased.

Charles I's life and execution have often been shown in popular culture today. Historians have retold the story of Charles I's fall and execution. Films and TV shows have used the drama of the execution for different reasons. This includes comedies like Blackadder: The Cavalier Years and historical dramas like To Kill a King. For a long time, there was not much serious academic study of the execution. This might be because people felt uncomfortable with such an "un-English" act as beheading their king. But this has slowly changed, and academic interest has grown, especially around the 350th anniversary in 1999.

See also

- Execution of Louis XVI

- Execution of the Romanov family

- King Charles the Martyr

- Fifth Monarchists

- Charles I Insulted by Cromwell's Soldiers

- Calves' Head Club

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |