Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Henry Stuart |

|

|---|---|

| Duke of Gloucester | |

Portrait by Jan Boeckhorst, c. 1659

|

|

| Born | 8 July 1640 Oatlands Palace, Surrey |

| Died | 13 September 1660 (aged 20) Palace of Whitehall, London |

| Burial | 21 September 1660 Westminster Abbey, London |

| House | Stuart |

| Father | Charles I of England |

| Mother | Henrietta Maria of France |

Henry Stuart, Duke of Gloucester (born July 8, 1640 – died September 13, 1660) was a prince of England. He was the youngest son of King Charles I and his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria of France. People also knew him as Henry of Oatlands.

From a young age, Henry and his sister Elizabeth were separated from their family. This happened during the English Civil War. They became prisoners of the Parliament. For several years, the children had to move often because of the plague in London. They also had different guardians who were loyal to the government.

In 1645, their older brother James, Duke of York, joined them. In 1647, King Charles I was arrested. He was allowed to see his children a few times. In April 1648, James escaped the country. It was likely planned for Henry to go with him, but Elizabeth was worried about her younger brother.

When Charles I was sentenced to death in 1649, he feared Henry would be made king by Parliament. He made his eight-year-old son promise not to take the crown while his older brothers were alive.

After Charles I was executed, Charles II, Henry's oldest brother, became king of Scotland. In 1650, Charles II landed in Scotland. Because of this, Parliament sent Henry and Elizabeth to Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. Their father had been held prisoner there before. Before leaving, Henry and Elizabeth lost all their royal titles. Soon after arriving, in September 1650, Elizabeth got sick and died.

Henry stayed at Carisbrooke until the next year. With Oliver Cromwell's permission, he went to Europe. He eventually joined his mother in Paris. Henry and his mother, Henrietta Maria, had not seen each other for eleven years. They did not get along well. Henry was a strong Protestant, and his mother was a strict Catholic. The Queen tried to make Henry become Catholic, even though his father and oldest brother did not want this. This only made their relationship worse.

Henry then went to his brother Charles in Cologne. In 1657, Henry fought alongside the Spanish against France with his brother James. In May 1659, Charles gave Henry back his title of Duke of Gloucester. Parliament had taken this title away in 1650. Charles also gave him the title of Earl of Cambridge.

After the monarchy was brought back to England in 1660, Henry went with his brother Charles II back to Britain. Henry received several important jobs. However, before Charles II's coronation, Henry caught smallpox and died. He was buried in Westminster Abbey, in the same place as his sister Mary, who also died of smallpox a few weeks later.

Contents

A Prince's Early Life and Birth

Henry was born on July 8, 1640, at Oatlands Palace in Surrey. He was the youngest son of King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria of France. The King and Queen had nine children in total. Henry was their fifth child to survive infancy.

His grandparents on his father's side were King James VI of Scotland and I of England and Anne of Denmark. His grandparents on his mother's side were King Henry IV of France and Marie de' Medici. When Henry was born, only Marie de Medici was still alive.

Henry was baptized on July 22, 1640. His older sister, Mary, was his only godmother. This was Mary's first public appearance. From birth, Henry was known as the Duke of Gloucester.

In early 1642, Henry's sister Mary and his mother left for The Hague. Henrietta Maria quickly said goodbye to Henry and Elizabeth at Hampton Court Palace. She would not see Henry again until 1653. In August 1642, the English Civil War began. Two-year-old Henry and his sister became hostages of the English Parliament.

Life During the English Civil War

When the civil war started in August 1642, King Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria had to leave Henry and Elizabeth with Parliament. In October 1642, the plague reached Hampton Court Palace, where the children lived. Elizabeth, who was often sick, became too weak to leave. So, the children moved to St James's Palace with Parliament's permission.

Parliament did not want to punish the children for their father's actions. However, they cut down on the money spent on the prince and princess. They also fired many servants who were not loyal to Parliament. Elizabeth managed to get some things changed for their household. But their chaplain was replaced, and their clothes became very plain.

In late 1642 and early 1643, two of the King's squires visited Henry and Elizabeth. Parliament allowed this to check on the children's health. Later, Henry and Elizabeth lost their clothing payments. This was because of the fight between King Charles I and Parliament. One member of Parliament said, "if the King wants to fight with us, they [children] must pay for clothes at their own expense!"

This made the King and the children's governess, the Countess of Roxburghe, very angry. She wrote a letter to Parliament. After discussions, Parliament decided to bring back the payments. However, all of Henry and Elizabeth's expenses had to be made public. The royal children were given £800 a month. An officer, Sir Ralph Freeman, watched over their spending. Parliament also checked the palace's religious staff to make sure the children were taught the "correct" religion. On July 20, 1643, the Countess of Roxburghe was replaced by the Countess of Dorset, who was loyal to the government.

In the summer of 1643, Parliament wanted to move Henry and Elizabeth to Oxford. But Elizabeth broke her leg, so the move was delayed. By summer 1644, Elizabeth had recovered. However, she soon became ill again. Doctors suggested a change of climate. So, the children moved to Chelsea, to the home of Sir John Danvers. He would later sign King Charles I's death warrant. During this move, Henry and Elizabeth did not get the usual royal escort.

The plague continued, so the prince and princess moved often. They went between St. James, Whitehall, and Chelsea. By winter, they were moved to Whitehall, which seemed safer than St. James's Palace, where the plague was active.

In early 1645, the Countess of Dorset, their governess, became very sick and died. Henry and Elizabeth were then placed with the Earl and Countess of Northumberland. This was announced in newspapers on March 13, 1645. The Earl was a good friend of the King. He treated the children with great respect. The royal children had a happy summer at one of the Earl's homes, likely Syon House. Elizabeth wrote about this to her older sister Mary on September 11, 1645.

On that same day, Parliament discussed how to care for the royal children. They agreed on the servants, the money needed, and where the children would live. The Earl of Northumberland chose St. James's Palace. Henry and Elizabeth soon moved there. The Earl also managed to reduce the number of guards for the children's comfort.

In September, Henry's brother, the Duke of York, was in a difficult situation. He was in Oxford, where the plague was spreading. He had many debts and no supplies. He wrote to his father, asking to join his brother and sister in London. The prince did not wait for his father's answer. Parliament approved the move. The Duke of York was brought to St. James Palace with a grand escort. He stayed with Henry and Elizabeth until April 1648.

Father's Arrest and Execution

In March 1647, the Earl of Northumberland moved the royal children to Hampton Court Palace. But they were soon called back to St. James Palace. At the same time, the Scots handed King Charles I over to the English Parliament. The King was to be arrested in Caversham. Before leaving, Charles I asked to see his children.

In summer 1647, due to a new plague, the Earl of Northumberland moved the royal children often. They ended up at Syon House. In August, the arrested King was moved to Hampton Court Palace. From there, on August 23, he was allowed to visit Syon House and see his children. On August 31, he visited again. On September 7, Henry, with his brother and sister, went to Hampton Court Palace to see their father. During one of these visits, the King insisted that his youngest son should not be pressured about religion. He also told all three children to be loyal to the Anglican Church but also to their Catholic mother.

In October, Parliament planned to move the children to St. James's Palace for the winter. The King asked Parliament to let the Earl of Northumberland send letters between him and his children. He also asked for them to visit him sometimes. His request was granted. But in November 1647, the King escaped.

When Elizabeth learned of her father's escape, she tried to convince her older brother, the Duke of York, to flee the country. This was probably based on instructions from Charles I. Thanks to Elizabeth's cleverness, James tricked his guards. Dressed as a woman, he escaped from Elizabeth's rooms to The Hague on April 21, 1648. He joined his sister Mary there. The King likely planned for Henry to escape with James. But Elizabeth was afraid to let Henry go because he was too young. After James's escape, Parliament investigated. They ordered the Earl of Northumberland to move Henry and Elizabeth to Syon House or Hampton Court. The Earl chose Syon House.

In August 1648, Charles I was captured again. But in October, he sent a letter to Elizabeth from Newport. He sent it with his trusted servant, Sir Thomas Herbert. Elizabeth had a long talk with Herbert about her father. The autumn and winter of 1648 were unclear for Henry and Elizabeth. They did not get more news from their father. Also, the Earl of Northumberland took them out of town for the whole winter. He did not tell them all the details of the King's trial, which horrified him.

However, the royal children knew that on January 26, 1649, Charles I was found guilty and sentenced to death. The day before the sentencing, he asked to see the children. A similar request was made on January 27. On January 29, the day before the execution, the King was allowed to see Henry and Elizabeth. After that, the royal children were returned to Syon House.

At their last meeting, Charles I gave instructions to his children. He worried that after his death, Henry might be made King and controlled by Parliament. The King knelt before his son and said: "Now they will take your father's head. Listen, my child, what I say: they will kill me and, perhaps, make you King. But remember what I say. You must not become King while your brothers Charles and James are both alive...I order you not to become King before them." Eight-year-old Henry replied that he would rather be torn apart first.

New Guardians and Sister's Death

There are no records of how the royal children spent January 30, 1649, the day of their father's execution. By this time, their guardian, the Earl of Northumberland, had grown very fond of Charles I's children. He was one of five English nobles who opposed the King's execution.

As a result, the royal children were moved to the care of the Earl and Countess of Leicester at Penshurst Place. Elizabeth did not want to move. She felt her new guardians would be less kind. She asked Parliament again to let her and Henry go live with their sister Mary in Holland. But her request was denied. The royal children, with the Countess of Leicester and ten or eleven servants, arrived at Penshurst on June 14, 1649.

At Penshurst Place, the Countess of Leicester mostly raised the royal children. The Earl was often in London. The Earl and Countess had many children, who became companions for Henry and Elizabeth. They ate at the table together, not with royal honors, but as part of the family. This was done based on Parliament's orders. Here, the royal children were lucky to have a tutor, Robert Lovel. He was a relative of the Earl of Leicester and supported the royal family.

Soon after they moved to the Leicester household, rumors spread. People said the royal children might be poisoned. Or they might be sent to an asylum or charity school under the names Harry and Bessie Stewart. There were also fears that the children would be forced into marriages. However, these rumors were likely spread by their mother, Henrietta Maria, who was in France. They probably had no real basis.

Parliament had a plan to take away all the royal children's privileges. They wanted to place them with a trusted family and raise them without much attention. But this plan did not happen. Right after Charles I was executed, Scotland named Henry's older brother, Charles II, as its new king.

In summer 1650, when it was known that Charles II had landed in Scotland, Parliament decided to move Henry and Elizabeth. They were sent to Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. Their father had been imprisoned there before. They were placed under the care of Anthony Mildmay and his wife. Elizabeth was horrified to be imprisoned in her father's former prison. She asked to stay at Penshurst Place because she was unwell. But she was not successful.

Before leaving for Carisbrooke Castle, the number of royal children's servants was cut to four. They lost their titles of prince and princess. Henry also lost his ducal title. Elizabeth was now called Lady Elizabeth Stewart, and Henry was called Harry Stewart or Mr. Harry.

On August 23, about a week after arriving at Carisbrooke Castle, Elizabeth became sick after playing outside. On September 8, 1650, at 3 p.m., she died. Ten-year-old Henry was left alone.

Life Away from England

Henry stayed at Carisbrooke Castle until 1652. Then, Oliver Cromwell allowed the prince to leave the country. He also gave him money for his travels. Henry went to Holland to his sister Mary. She and other relatives welcomed him warmly. Here, on Easter Sunday 1653, the prince was made a knight of the Order of the Garter.

Then, his mother invited him to join her in Paris. In 1653, his older brother Charles II went to Germany. He moved his court there a year later. Charles offered to take Henry with him. But their mother insisted that Henry stay in Paris. Henrietta Maria believed that Henry, after being in England for so long, should improve his education in France's capital. Charles II agreed, but only if his mother would not force Henry to change his religion.

Henry had not seen his mother since he was two years old. They did not get along well. During their separation, Henry had become a strong Protestant. Henrietta Maria was a firm Catholic. Charles I's widow went against the wishes of her oldest son and her late husband. She had promised not to make her youngest sons change their faith. But she tried to convert Henry, and also her other son, James, Duke of York, to Catholicism. James became interested in his mother's religion, but he did not convert until many years after her death.

Henrietta Maria could not stop trying to make her youngest son Catholic. She believed that only the true church could save his soul. At first, she was careful. She even let his Anglican teacher, Robert Lovel, stay with him. Henry visited his brother James. When he returned to Paris, he found that his teacher had been sent back to England. The prince was then placed under the care of Walter Montagu. He was the Aumônier (chaplain) of Henrietta Maria and an abbot of a monastery near Pontoise. Montagu was supposed to teach fourteen-year-old Henry about religion.

Without Lovel, Henry listened to the abbot's suggestions. He agreed to learn about Catholicism. But he was very angry about his mother's actions. When she did not get a quick result, Henrietta Maria joined Montagu. She began to persuade her son to change his religion. But Henry was firm. So, they decided to send him to a Jesuit College.

When Charles II heard about his mother's actions, he became very angry. He immediately sent the Marquess of Ormonde to Paris. Ormonde's job was to bring Henry to him in Cologne. At first, Henry refused to leave Paris, and Ormonde agreed with him. Henry told his mother that he would stick to the Protestant religion no matter what. She then said she did not want to see him anymore.

When Henry returned from another Anglican service, he found that his horses had been taken from the stables. His bed had no bedding. Orders had been given not to cook food for him. This meant the prince was effectively kicked out of the palace. Henry moved into Lord Hutton's house. He stayed there for two months while the Marquess of Ormond gathered money to send the prince to his brother in Cologne. So, Henrietta Maria's attempts to make Henry Catholic failed. They also angered the royalists and Charles II. And they completely ruined her relationship with her younger son.

Henry stayed with Charles in Cologne until 1656. In July 1655, their sister Mary visited them. Then, they all traveled to Frankfurt. They visited a fair secretly, but people still recognized them. Before this, Henry had also visited Mary in the Netherlands a few times, both with his brother and alone.

In 1656, the brothers left for Bruges. Henry became a member of the Archers of Saint George there. In December 1656, Henry became a colonel in the "old" English regiment of the Spanish army. He and his brother James volunteered to serve the Spanish in 1657 in the Low Countries. Their mother was against this. She thought Henry was too young to be a soldier. But the prince did not listen to her. He fought bravely alongside his brother in the defense of Dunkirk on June 17, 1658. Both showed great courage. When the city fell, Henry managed to escape capture. He gathered some scattered troops and bravely broke through the enemy lines. In the battle, the prince lost his sword. While Villeneuve, an officer, looked for the sword, Henry protected him with a pistol.

On February 26, 1657 or 1658, Charles II made his brother a knight. On October 27, 1658, he made him a member of his Privy Council. And on May 13, 1659, he gave him back the title of Duke of Gloucester. He also gave him the title of Earl of Cambridge.

Return to England and Death

After the monarchy was brought back to England in 1660, Henry went with his brother Charles II back to their home country. Parliament paid for their trip. Henry settled in the Palace of Whitehall. On June 31, 1660, he was already sitting in the House of Lords. On June 13, he was made Chief Steward of Gloucester. On July 3, he became Ranger of Hyde Park.

In early September 1660, Henry caught smallpox. This disease was spreading in London at the time. The prince died on September 13, 1660, before his brother Charles II's coronation. On September 21, his body was moved to Somerset House. From there, it was taken by river to Westminster. He was buried in Westminster Abbey in the vault of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Henry's death made the joy of the family reunion less happy. A few weeks later, Henry's older sister Mary, Dowager Princess of Orange, also died of smallpox. On her deathbed, she wished to be buried next to her brother.

The Earl of Clarendon, a historian and statesman, wrote highly of Henry. He called him one of the finest young men, "the most manly...that I ever knew." He also described him as "a prince of extraordinary hopes, who had a personality of comely and graceful with liveliness and the power of reason and understanding." Gilbert Burnet believed that the prince "had a different character than any of his brothers. He was active and liked to do things, had a penchant for special friendships, and a quirky personality that tended to be very pleasant." Burnet wrote that "his death was mourned by many, especially the King, who had never been so upset."

Charles II had planned for Henry to marry Princess Wilhelmine Ernestine of Denmark. This was meant to strengthen the alliance between England and Denmark. King Frederick III of Denmark also agreed to the marriage. But the prince's early death stopped this union. Henry's death meant that the throne eventually went to William III and Mary II. They were the children of Henry's older sister and older brother. Later, the throne passed to the House of Hanover.

Titles and Honors

Titles

Henry was likely known as the Duke of Gloucester and Earl of Cambridge from birth. These titles were officially restored to him on May 13, 1659.

Honors

- KG: Knight of the Garter, April 4, 1653

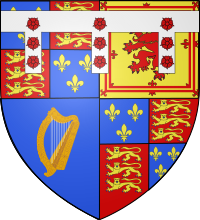

Arms

Henry's own coat of arms was based on the royal coat of arms of the Stuarts. It showed a shield with a silver "tournament collar." This collar had a Tudor rose (a red rose with a silver center and green leaves) on each point.

The shield itself was divided into four parts:

- In the 1st and 4th parts: The English royal coat of arms (three golden lilies on a blue background, and three golden leopards on a red background).

- In the 2nd part: The coat of arms of Scotland (a red lion on a golden background, surrounded by a special border).

- In the 3rd part: The coat of arms of Ireland (a golden harp on a blue background).

A crown, suitable for a monarch's child, sat above the shield. Above the crown was a crest: a golden leopard wearing a silver collar like the one on the shield. The shield was surrounded by the dark blue velvet ribbon of the Order of the Garter. This ribbon had a gold border and the Latin words: "Honi soit qui mal y pense" ("Shame on him who thinks ill of it").

Elias Ashmole's book about the Order of the Garter shows a coat of arms with three roses (one above the other) on each point of the collar.

See also

In Spanish: Enrique Estuardo (1640-1660) para niños

In Spanish: Enrique Estuardo (1640-1660) para niños