Restoration (Scotland) facts for kids

The Restoration was a time when the king returned to power in Scotland in 1660. This happened after a period called the Commonwealth, when Scotland was ruled by a government without a king. The Restoration lasted for about 30 years, until the Revolution in 1689.

This event was part of a bigger "Restoration" across Britain and Ireland. It brought the Stuart dynasty back to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Charles II became king again.

George Monck, who was in charge of the army in Scotland, played a big part in bringing Charles II back. Charles was declared king in Edinburgh on May 14, 1660. Most people were forgiven for things they did during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. However, a few people were punished.

Scotland got back its own laws, parliament, and church (called the kirk). But it also got back the Lords of the Articles and bishops. The king, Charles II, didn't visit Scotland often. He ruled mostly through special representatives called commissioners. The first was the Earl of Middleton, and the last was the king's brother, James, Duke of York.

Bringing back bishops to the Scottish church caused many problems. There were fights between Presbyterians and the bishops. This led to a difficult time for Presbyterians, known as The Killing Time.

Charles II died in 1685. His brother, James, became King James VII of Scotland (and James II of England). James faced some rebellions, but he upset many people because he was Catholic and tried to change things too quickly. In 1688, William of Orange from the Netherlands, who was James's Protestant son-in-law, invaded England. James ran away, and William and his wife, Mary, became the new rulers.

William called a special meeting in Scotland, the Scottish Convention. Presbyterians were mostly in charge of this meeting. They offered the crown to William and Mary. After James's supporters were defeated, bishops were removed from the church, and the Presbyterian system was put back in place.

During this time, Scotland's economy generally did well. However, getting back independence meant new trade rules with England. The return of the king also brought back the power of the nobles. But they seemed to use their power more carefully. Local landowners, called lairds, also gained more power.

There were attempts to bring back theatre, which had struggled. New styles of country houses appeared, focusing more on comfort and beauty. Foreign artists were very important for sculpture. Scotland had its own talented artists and welcomed many from other countries. Many important Scottish cultural and learning groups were started between 1679 and 1689.

Contents

- Scotland's Troubles: Civil Wars and Commonwealth Rule

- The King Returns: End of the Republic

- A Fresh Start: Pardon and Exceptions

- New Rules: The Settlement

- King Charles II's Representatives (1661–1685)

- James VII and the Glorious Revolution (1685–1689)

- Scotland's Economy: Trade and Growth

- Society in Scotland: Power and Change

- Culture in the Restoration Era

- Images for kids

Scotland's Troubles: Civil Wars and Commonwealth Rule

In 1638, King Charles I tried to change the Church of Scotland. This led to wars called the Bishop's Wars. These were the first of many fights between 1638 and 1651, known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

A group called the Covenanters took control of the Scottish government. At first, they stayed out of the First English Civil War in 1642. But many Scots worried about what would happen if the King's side won. They thought joining with England would protect their church. In October 1643, the English Parliament signed an agreement called the Solemn League and Covenant. This meant Scotland would help England fight, and in return, England would consider a union.

Some people, like Oliver Cromwell, didn't like this idea. They didn't want a state-controlled church. When the First Civil War ended in 1647, the Covenanters and their English friends tried to bring Charles I back to power. He agreed to make Presbyterianism the church in England but wouldn't become a Presbyterian himself. This caused a split among the Covenanters. Some, called Engagers, accepted this. Others, called the Kirk Party or Whiggamores, did not. After Cromwell won the Second English Civil War, he put the Kirk Party in charge of Scotland.

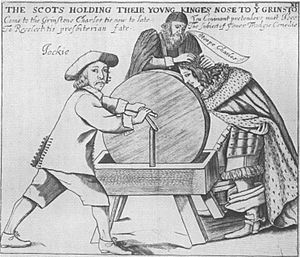

This alliance ended when Charles I was executed in January 1649. Both Engagers and the Kirk Party believed kings were chosen by God. They saw his execution as a terrible act. In February, the Scots declared Charles II King of Scotland and Great Britain. In the Treaty of Breda, they agreed to help him get the English throne back. In return, he accepted their Covenant. He was also forced to disown a rebellion by Montrose, a Royalist leader, who was then captured and executed. Charles never forgot this humiliation.

After losing the Third English Civil War in 1651, Cromwell decided the only way to have peace was to weaken the church and the powerful landowners in Scotland. He made Scotland part of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. Scottish representatives even sat in the London Parliament. This union wasn't fully legal until 1657. Scotland was ruled by the army under George Monck. He brought law and order and some religious freedom. But he used English judges and it was expensive, so many Scots didn't like it.

Unlike England, almost all Scots belonged to the same church and shared the same beliefs. The main disagreements were about how the church should be run. Monck's government made these divisions worse. This affected Scottish politics for a long time.

The King Returns: End of the Republic

George Monck, the leader of the biggest army in the Commonwealth, was key to bringing Charles II back. After Cromwell died in 1658, Monck stayed out of the power struggles in London. When no one could form a stable government in 1659, Monck started talking with Charles II. He then marched his army slowly south.

Once in London, Monck brought back the English Parliament that had existed at the start of the civil wars. This Parliament got promises from Charles II and then voted to bring back the king in England. This meant the king was also back in Scotland, but without any clear rules for Scotland's government. Scottish leaders were in a weak position to negotiate with the king. Charles II made Monck the Duke of Albemarle to thank him.

Charles was declared king in Edinburgh on May 14, 1660. This was the second time; he had been declared king in 1649. He wasn't crowned again in Scotland. People across Scotland celebrated his return. Charles II called his Parliament on January 1, 1661. This Parliament began to undo all the laws that had been forced on his father, Charles I. The Rescissory Act 1661 cancelled all laws made since 1633.

A Fresh Start: Pardon and Exceptions

On September 9, 1662, the Scottish Parliament passed an important law called the Act of indemnity and oblivion. This law offered a general pardon for most crimes committed by Scots between 1637 and 1660. These years were called "the late troubles" (the civil wars).

The law was similar to one in England. It offered a general pardon but listed many exceptions. It did not cancel any laws passed by the Scottish Parliament since August 1660. The law specifically named people like Archibald Campbell, Archibald Johnston, and others. Another law added heavy fines for about 700 people who had supported the Covenanters. If these people paid their fines on time, they would get the pardon.

A few people from the old government were tried and found guilty of treason. Archibald Campbell was beheaded in 1661. James Guthrie and Captain William Govan were hanged in 1661. Archibald Johnston was hanged in 1663. Others faced prison or had their lands taken away.

New Rules: The Settlement

After the king returned, Scotland got back its own legal system, Parliament, and church. But it also got back the Lords of the Articles (a powerful committee) and bishops in the church. The king didn't visit Scotland much. He ruled mostly through special representatives called commissioners. The first was the Earl of Middleton, and the last was the king's brother, James, Duke of York.

Bishops Are Back: The Church Changes

Presbyterians had hoped Charles would make the church Presbyterian, as he had agreed to the Solemn League and Covenant. The "Act Recissory" cancelled laws from 1633, undoing what the Covenanters had gained. But another law that same day kept some church rules, suggesting a compromise was possible.

However, on September 6, 1661, the Privy Council of Scotland announced that bishops would be back. James Sharp, a minister, changed his mind and became Archbishop of St Andrews. Soon, a full group of bishops was in place. In 1662, the Church of Scotland was officially restored as the national church. Everyone holding a church job had to reject the Covenants.

About one-third of the ministers, at least 270, refused to accept these changes. Most of these were in the southwest of Scotland, where Covenanting beliefs were strong. Some of these ministers started preaching outdoors in large gatherings called conventicles. Thousands of people would come to listen.

King Charles II's Representatives (1661–1685)

Middleton (1661–1663)

The king's first step in Scotland was to choose government officials and members of the Privy Council without asking Parliament. William Cunningham, 9th Earl of Glencairn became Chancellor, and John Leslie, Earl of Rothes became President of the council. A new Scottish Council was set up in London, led by James Maitland, Earl of Lauderdale. John Middleton, a former Covenanter and soldier, was made Commissioner.

A new Parliament met on January 1, 1661. It passed 393 laws, strongly supporting the church structure with bishops and the king's power over government. In 1663, Middleton tried to pass a law forcing all officials to say the Covenants were illegal. This was an attack on people like Lauderdale, who was close to the king. As a result, Middleton was removed and replaced by Rothes.

Rothes (1663–1666)

Rothes worked closely with Lauderdale. In 1663, Parliament passed a law called the "Bishop's Dragnet." This law said that ministers who disagreed with the church were troublemakers. It allowed big fines for people who didn't go to their local churches. Soon after, Parliament was dismissed and wouldn't meet again for six years.

In 1666, a group of people from Galloway who disagreed with the church captured a local army commander, Sir James Turner. They marched towards Edinburgh. There were about 3,000 men at most, but by the time they were defeated at the Battle of Rullion Green, their numbers had shrunk. Many prisoners were executed or sent away to Barbados. This uprising led to Rothes being removed as Commissioner. Lauderdale then returned from London to take over.

Lauderdale (1666–1679)

Lauderdale tried to be more understanding. He issued "Letters of Indulgence" in 1669, 1672, and 1679. These allowed ministers who had been removed to return to their churches if they avoided political protests. But 150 ministers refused, and some who supported bishops were unhappy with this compromise.

When compromise failed, the government became stricter again. Preaching at an outdoor meeting (conventicle) could be punished by death. Attending one also had severe penalties. In 1674, landowners were made responsible for their tenants and servants. From 1677, they had to promise that everyone on their land would behave. In 1678, 3,000 Lowland soldiers and 6,000 Highlanders were sent to live in the areas where Covenanters were strong, as a form of punishment.

In 1679, a group of Covenanters killed Archbishop James Sharp. This led to a rebellion that grew to 5,000 men. They were defeated by forces led by James, Duke of Monmouth, the king's son, at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge on June 22. Two ministers were executed, and 250 followers were sent to Barbados. About 200 of them drowned when their ship sank near Orkney. This rebellion eventually led to Lauderdale being replaced by the king's brother, James, Duke of York.

Duke of Albany (1679–1685)

The king sent his brother, James, to Edinburgh. This was mainly to get him away from London during a time when some English politicians tried to stop James from becoming king because he was Catholic. James lived in Holyrood Palace in the early 1680s, running a small court there.

The people who disagreed with the church, led by Donald Cargill and Richard Cameron, called themselves the Society People. They later became known as the Cameronians. Their numbers were small, and they hid in the moors, becoming more extreme. On June 22, 1680, they put up the Sanquhar Declaration in Sanquhar, saying they no longer recognized Charles II as king. Cameron was killed the next month. Cargill declared the king and others outside the church. His followers then separated from all other Presbyterian ministers. Cargill was captured and executed in May 1681.

The government passed a Test Act, forcing every public official to swear an oath of loyalty. Eight church leaders and James Dalrymple, a top judge, resigned. The important nobleman Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll was forced to leave the country.

In 1684, the remaining Society People put up a declaration saying they would fight back against anyone who tried to harm them. In response, the Scottish Privy Council allowed soldiers to execute people on the spot if they were caught with weapons or refused to swear loyalty to the king. This harsh period, known as "the Killing Time", saw many people executed by soldiers or sent away.

James VII and the Glorious Revolution (1685–1689)

Charles II died in 1685. His brother, James, became King James VII of Scotland (and James II of England). James put Catholics in important government jobs. Even attending an outdoor church meeting was made punishable by death. He ignored Parliament and tried to force religious toleration for Roman Catholics. This made his Protestant subjects very unhappy.

An invasion led by the Earl of Argyll, planned with a rebellion in England, failed. This showed how strong James's government was. However, a riot in response to Louis XIV's actions against Protestants in France showed how strong anti-Catholic feelings were. The king tried to get tolerance for Catholics by issuing "Letters of Indulgence" in 1687. These also allowed freedom of worship for Protestants who disagreed with the church. This meant Presbyterian ministers could return to their churches. But it didn't include outdoor meetings, and the Society People continued to suffer. Their last minister, James Renwick, was captured and executed in 1688.

People thought the king's daughter, Mary, a Protestant married to William of Orange of the Netherlands, would become queen. But in 1688, James had a son, James Francis Edward Stuart. This meant his Catholic policies would continue. Seven important Englishmen invited William to invade England. He landed with 40,000 men on November 5.

In Edinburgh, there were rumors of plots against the king. On December 10, the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, the Earl of Perth, left the capital. Rioters approached Holyrood Abbey and were fired on by soldiers, causing some deaths. The city guard was called, but a large crowd stormed the Abbey. They tore down the Catholic decorations and damaged the tombs of the Stuart kings. Students burned an effigy of the Pope and took down the heads of executed Covenanters hanging above the city gates. The crisis ended when James fled from England on December 23. This led to a mostly peaceful revolution.

Most members of the Scottish Privy Council went to London to offer their help to William. On January 7, 1689, they asked William to take over the government.

William called a Scottish Convention, which met in Edinburgh on March 14. Presbyterians were mostly in charge. Some supported James, including many who liked bishops, but they were divided by James's attempts to help Catholics. A letter from James, received on March 16, threatened to punish anyone who rebelled against him. This made his supporters leave the convention, leaving William's supporters in control.

On April 4, the Convention wrote the Claim of Right. This document said James had lost his right to the crown because of his actions. It offered the crown to William and Mary, which William accepted, along with limits on royal power. On May 11, William and Mary became King William II and Queen Mary II of Scotland.

The final agreement, completed by William's Parliament in 1690, brought back Presbyterianism and removed the bishops, who had generally supported James. Ministers who had been removed in 1662 were brought back. This ended the harsh treatment of the Cameronians, leaving only a few outside the church. The church refused to bring back even those ministers who had supported bishops but now accepted Presbyterianism. However, the king issued two acts in 1693 and 1695, allowing those who accepted him as king to return to the church. Most people who had supported James would be tolerated by 1707.

Scotland's Economy: Trade and Growth

Under the Commonwealth, Scotland was taxed heavily but could trade freely with England. After the king returned, the border with England was put back, along with customs taxes. The economy generally did well from 1660 to 1688. Landowners improved farming and cattle raising.

The special right of royal burghs to control foreign trade was partly ended by a law in 1672. They kept control of luxury goods like wines and silks. But trade in important goods like salt, coal, and hides, and imports from the Americas, was opened up.

The English Navigation Acts made it hard for Scots to trade with England's growing colonies. But Scots often found ways around these rules. Glasgow became an important trading city, bringing in sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia. Scotland exported linen, wool, coal, and grindstones across the Atlantic.

English taxes on salt and cattle were harder to avoid and probably hurt the Scottish economy more. Scotland's attempts to put its own taxes on English goods didn't work well because Scotland didn't have many vital exports to protect. The government's efforts to start luxury industries like cloth mills and sugar factories were mostly unsuccessful. However, by the end of the century, drover's roads, used for moving cattle from the Highlands to England, were well established. Famines became rare in the second half of the 1600s, with only one bad harvest year in 1674.

Society in Scotland: Power and Change

Nobles were very powerful in Scottish politics in the first half of the 1600s. They lost some power during the Commonwealth period, as the government ruled without them. But they got their power back when the king returned, along with the traditional government bodies. However, some historians believe they used their power more carefully after the civil wars.

As old feudal ranks changed, barons and tenants-in-chief became known as lairds (landowners). Under the Commonwealth, they served as Justices of the Peace, a role that became more important. They also gained power by becoming Commissioner of Supply in 1667. This job gave them responsibility for collecting local taxes. New laws that allowed landowners to move boundaries, roads, and enclose land also helped this group. Laws that brought back a form of serfdom for miners and saltworkers also benefited them.

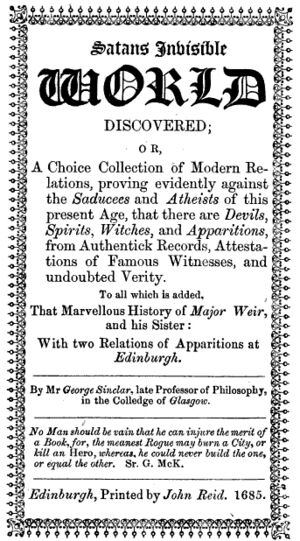

Scotland had a much higher rate of witchcraft trials compared to England or Europe. Most cases were in the Lowlands, where the church had more control. Under the Commonwealth, English judges were against torture and often doubted the evidence from it. This led to fewer witchcraft trials. To gain support from landowners, Sheriff's courts were brought back, and Justices of the Peace returned in 1656. This resulted in a wave of witchcraft cases, with 102 between 1657 and 1659.

When the king returned, the limits on trials were removed. There was a huge increase in cases, over 600, which was the largest in Scottish history. This worried the Privy Council. They started to require their permission for arrests or trials and banned judicial torture. Trials became more controlled by judges and the government. Torture was used less, and evidence standards were raised. The exposure of "prickers" (people who claimed to find witches by pricking them) as frauds in 1662 removed a major type of evidence. The Lord Advocate Sir George Mackenzie also worked to make trials less effective. People may have also become more skeptical. With more peace and stability, the social problems that led to accusations were reduced. Witchcraft trials eventually stopped when the law supporting them was cancelled in 1736.

Culture in the Restoration Era

Theatre Returns

When James VI became King of England and Ireland in 1603, Scotland lost its royal court. The church was also against theatre. This meant theatre struggled in Scotland during the 1600s. After the Restoration, there were efforts to bring back Scottish plays.

In 1663, William Clerke wrote Marciano or the Discovery, a play about a king returning to power. It was performed at Holyrood Palace. Thomas Sydsurf's Tarugo's Wiles or the Coffee House was first performed in London in 1667 and then in Edinburgh. Sydsurf also managed the Tennis-Court Theatre and had a group of actors in Edinburgh. The plays performed were similar to those in London.

The Duke of Albany brought actors with him when he lived at Holyrood. He also had Irish actors. He encouraged court masques (plays with music and dancing) and seasons of plays at the Tennis-Court Theatre. Even Princess Anne, who would later become Queen, acted in one of these plays.

New Architecture Styles

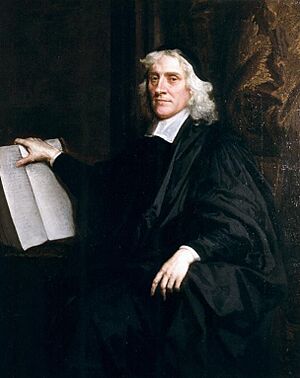

The Restoration brought a new style of country house to Scottish nobles. This style focused more on comfort and beauty, similar to what was already popular in Europe. Sir William Bruce (around 1630–1710) was key in bringing the Palladian style to Scotland. Bruce was inspired by English architects like Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren.

Bruce built and changed country houses, including Thirlestane Castle and Prestonfield House. One of his most important works was his own Palladian mansion at Kinross, built in 1675. As the king's architect, Bruce also rebuilt Holyroodhouse in the 1670s, giving it its current look. After Charles II died in 1685, Bruce lost favor.

James Smith (around 1645–1731) worked on Holyrood Palace. In 1683, he became the main architect for royal buildings. With his father-in-law, Robert Mylne, Smith worked on Caroline Park in Edinburgh (1685) and Drumlanrig Castle (1680s). Smith's country houses followed Bruce's style, with sloped roofs and front sections with triangular tops.

Artistic Flourish

Sculpture was mostly done by artists from other countries. The statue of Charles II outside Parliament House (1684/5) was a copy of a bronze statue in England. It was the first in Britain to show a king in classical clothing. John Van Ost (active 1680–1729) made lead garden statues for Hopetoun House and Drumlanrig Castle.

William Bruce preferred Dutch carvers for Kinross House. These artists created decorations like garlands and horn-shaped ornaments around doorways. Jan van Sant Voort, a Dutch carver living in Leith, made a carved decoration for Bruce in 1679 and worked on Holyrood Palace. From 1674, London plasterers George Dunsterfield and John Houlbert worked for Bruce at Thirlestane and Holyroodhouse.

John Michael Wright (1617–1694) learned from George Jamesone, an important Scottish artist. Wright also studied in Rome and painted portraits of both Scottish and English people. His portrait of William Bruce (1664) is well-known. His full-length painting of Lord Mungo Murray in Highland dress (around 1680) is an early example of what became a common style for Scottish portraits.

Another important artist was David Paton (active 1668–1708). He mostly drew with lead pencil but also painted portraits in oil. Visiting artists included Jacob de Wett (around 1610–around 1691). He was hired in 1684 to paint images of 110 kings for Holyroodhouse and did similar work at Glamis Castle.

Growing Intellectual Life

Between 1679 and 1689, many important groups for Scottish culture and learning were started. These included the Royal College of Physicians in 1681. Three professors of medicine were appointed at the University of Edinburgh in 1685. James VII created the Order of the Thistle in 1687. The Advocates Library, planned since 1682, opened in 1689. New royal positions like Royal Physician and Royal Historian were created between 1680 and 1682.

Right after the Restoration, Presbyterians were removed from universities. But most of the learning advances from before were kept. The five Scottish universities recovered well. They offered lectures that covered economics and science, giving a good education to the sons of nobles and landowners. All universities started or restarted mathematics departments. Astronomy was helped by building observatories at St. Andrews and in Aberdeen. Robert Sibbald became the first Professor of Medicine at Edinburgh and helped start the Royal College of Physicians in 1681.

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |