Economy of Scotland in the early modern period facts for kids

The economy of Scotland in the early modern era covers how people made money and traded goods in Scotland from the early 1500s to the mid-1700s. This time period is often called the early modern era in Europe. It began with the Renaissance (a time of new ideas) and the Reformation (changes in religion). It ended around the time of the last Jacobite risings (rebellions) and the start of the Industrial Revolution.

At the beginning of this period, Scotland was a relatively poor country. It had tough land and limited ways to transport goods. Most people relied on old farming methods. The late 1500s brought tough times, including rising prices and famines. But new ways of making things also started. The 1600s saw the economy grow, especially through trade with England and the Americas. However, famines still happened, with the "seven ill years" in the 1690s being very bad. A big plan to start a Scottish colony in Central America, called the Darién scheme, failed terribly in the 1690s.

After Scotland joined with England in 1707, forming Great Britain, farming methods improved. This helped provide more food. Trade with the Americas also grew, leading to the rich Tobacco Lords in Glasgow. They traded in sugar and rum. The town of Paisley became known for cloth. New financial groups like the Bank of Scotland and Royal Bank of Scotland were created. Roads also got better. All these changes helped set the stage for the Industrial Revolution, which really took off later in the 1700s.

Contents

Scotland's Economy in the 1500s

Farming Life and Methods

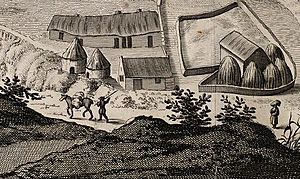

Scotland was often seen as a poor country. In the early 1500s, bad roads and limited transport meant most places relied on what they grew nearby. There was often little extra food for bad years. Most farming happened in small settlements called fermtouns in the lowlands or bailes in the highlands. These were groups of a few families who farmed an area together.

They used a system called run rig. This meant land was divided into strips, or "runs" and "rigs." These strips often ran downhill to include both wet and dry land. This helped protect against extreme weather. Farmers mostly used heavy wooden ploughs with iron blades. These were pulled by oxen, which worked better in Scotland's heavy soil and were cheaper to feed than horses.

Trade and Exports

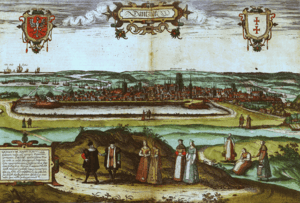

Trade slowly grew in the 1530s but suffered during English invasions in the 1540s. From the mid-1500s, demand for Scottish cloth and wool in Europe went down. So, Scots sold more traditional goods like salt, herring, and coal. The importance of different Scottish towns (called burghs) in foreign trade changed. Haddington, once a big trade center, saw its trade collapse. Aberdeen's trade stayed steady but then dropped. Smaller ports in Fife became more important, and Edinburgh's port, Leith, handled more and more trade. This made smaller ports find new things to trade or focus on coastal shipping. Overall, foreign trade increased from the 1570s, with Edinburgh getting most of it.

Women's Role in the Economy

Women were a very important part of the workforce. Many unmarried women worked as farm servants away from their families. Married women worked with their husbands on the farm, helping with all the main tasks. They were especially important during harvest as "shearers," cutting crops.

Women also played a big part in the growing textile (cloth) industries. They would spin yarn and prepare the "warp" (the lengthwise threads) for men to weave. Single women, especially widows, sometimes ran their own businesses. They might keep schools, brew ale, or trade goods.

Economic Hardship and New Industries

The late 1500s was a tough time for the economy. Taxes increased, and money lost its value. For example, in 1582, a pound of silver was worth 640 shillings, but by 1601, it was 960 shillings. Wages went up quickly, but not fast enough to keep up with rising prices. There were also many harvest failures. Almost half the years in the second half of the 1500s saw food shortages. This meant Scotland had to import large amounts of grain from the Baltic Sea region, especially from Poland through the port of Danzig. Scottish communities even formed in these ports. Outbreaks of plague also made things worse, with major epidemics from 1584–88 and 1597–1609.

Despite the difficulties, new industries began to appear. Often, experts from other countries helped. For example, a Venetian helped start a glass-blowing industry. George Bruce of Carnock used German methods to solve water problems in his coal mine at Culross. In 1596, the Society of Brewers started in Edinburgh, and English hops allowed for better Scottish beer to be made.

Scotland's Economy in the 1600s

Growing Trade and Taxes

In the early 1600s, famine was common, with four periods of high food prices between 1620 and 1625. English invasions in the 1640s badly hurt Scotland's economy. Crops were destroyed, and markets were disrupted, causing prices to rise very quickly. When England and Scotland were united under the Commonwealth, Scotland was taxed heavily but gained access to English markets.

After the king returned (the Restoration), customs duties (taxes on goods) were put back in place between Scotland and England. From 1660 to 1688, economic conditions were generally good. Landowners worked to improve farming and cattle raising. In 1672, the special right of royal burghs to control all foreign trade was partly ended. They kept control over luxury goods like wines and silks. But trade in important goods like salt, coal, grain, hides, and goods from the Americas was opened up to others.

The English Navigation Acts limited Scotland's ability to trade directly with England's colonies. But Scots often found ways around these rules. Glasgow became an important trade center, bringing in sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia and Maryland. Scotland exported linen, wool, coal, and grindstones across the Atlantic. English taxes on salt and cattle were harder to avoid and likely hurt the Scottish economy. Scottish attempts to put their own taxes on goods were not very successful. By the end of the century, "drover's roads" were well-established. These were paths used to drive cattle from the Highlands to northern England.

The "Seven Ill Years"

The last ten years of the 1600s saw the good economic times end. Trade with the Baltic and France dropped from 1689–91 due to French trade rules and changes in the Scottish cattle trade. This was followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696, 1698-99). These years are known as the "seven ill years." This led to severe famine and a drop in population, especially in the north. These famines were seen as very bad because such widespread hunger had become rare in the late 1600s. They were also the last of their kind.

In 1695, the Scottish Parliament made plans to help the economy. They set up the Bank of Scotland. The "Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies" was given permission to raise money from the public. New sugar houses in Glasgow and Leith were encouraged to make sugar and rum using imported sugar.

The Darién Scheme Disaster

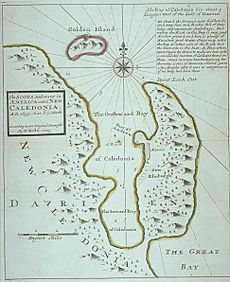

The "Company of Scotland" invested in the Darien Scheme. This was a big plan by William Paterson, who founded the Bank of England. He wanted to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama to trade with the Far East. Many people in Scotland supported the Darién scheme. Landowners and merchants believed that overseas trade and colonies would make Scotland richer.

Since the rich merchants and landowners in Edinburgh didn't have enough money, the company asked ordinary people to invest. They responded with great national pride. However, both the English East India Company and the English government were against the idea. The East India Company saw it as a threat. The English government was fighting a war against France and didn't want to upset Spain, which claimed the land. English investors then pulled out.

Back in Edinburgh, the Company raised £400,000 in just a few weeks. Three small fleets with 3,000 men set off for Panama in 1698. The plan was a complete disaster. The colonists were poorly equipped, suffered from constant rain and disease, and were attacked by the Spanish. The English in the West Indies refused to help them. The colonists gave up the project in 1700. Only 1,000 survived, and only one ship made it back to Scotland. The cost of £150,000 put a huge strain on Scotland's money system. It also caused widespread anger against England. This disaster showed the problems of having two separate economic policies and increased pressure for Scotland to fully unite with England.

Scotland's Economy in the Early 1700s

Improvements in Farming

After the Union of 1707, England had about five times Scotland's population and much more wealth. However, Scotland began to see its economy grow, helping to close this gap. Contact with England led Scottish landowners to try and improve farming. They started making hay, using English ploughs, and planting new grasses like rye grass and clover. Turnips and cabbages were introduced. Land was fenced off, marshes were drained, and lime was added to the soil. New roads were built, and trees were planted. Farmers also started drilling and sowing seeds and using crop rotation (changing crops each year to keep the soil healthy).

The potato was brought to Scotland in 1739, which greatly improved the diet of ordinary people. The old runrig system of shared land began to be replaced by Enclosures (fenced-off fields). In 1723, the Society of Improvers was founded, with 300 members, including dukes, earls, and landowners. Different regions started to specialize. The Lothians became a major grain area, Ayrshire focused on cattle breeding, and the Borders on sheep. However, while some landowners helped their displaced workers, enclosures often led to job losses and forced people to move to towns or abroad.

Trade and Early Industry

A major change in international trade was the fast growth of the Americas as a market. Glasgow sent cloth, iron farm tools, glass, and leather goods to the colonies. At first, Glasgow used hired ships, but by 1736, it had 67 of its own ships, with a third trading with the New World. Glasgow became the center of the tobacco trade, especially re-exporting it to France. The merchants who made huge profits from this business became known as the wealthy tobacco lords. They controlled Glasgow for much of the century.

Other towns also benefited. Greenock made its port bigger in 1710 and sent its first ship to the Americas in 1719. It soon became important for importing sugar and rum.

Most cloth was made at home. Rough plaids were produced, but the most important type of cloth was linen, especially in the Lowlands. Some people thought Scottish flax (used for linen) was even better than Dutch flax. Scottish members of parliament stopped a tax on linen exports. From 1727, linen received government money, which helped the trade grow a lot. This money came from the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, which used funds set aside at the Union. It gave £6,000 a year to encourage industries, especially linen and fishing. Paisley adopted Dutch methods and became a major center for linen production. Glasgow made linen for export, and its export trade doubled between 1725 and 1738. The British Linen Company also helped by giving cash loans, which boosted production. Soon, "manufacturers" managed the trade. They supplied flax to spinners, bought back the yarn, gave it to weavers, and then bought and resold the finished cloth.

Banking also grew during this time. The Bank of Scotland was thought to support the Jacobites (supporters of the old royal family), so a rival, the Royal Bank of Scotland, was founded in 1727. Local banks also started in towns like Glasgow and Ayr. These banks provided money for businesses and for improving roads and trade. All these changes helped create the right conditions for the Industrial Revolution, which sped up in the second half of the 1700s.

See also

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |