Economic history of Scotland facts for kids

The economic history of Scotland tells the story of how Scotland's economy has grown and changed over time. For seven centuries, Scotland was an independent country. Then, after joining with England in 1707, it became part of the United Kingdom.

Before the 1700s, Scotland was mostly a poor farming country. It didn't have many natural resources or advantages. It was also far away from the main trading routes in Europe. Many people left Scotland from the 1700s into the 1900s, moving to England or North America.

After 1800, Scotland's economy grew quickly. It became a major industrial country, making textiles, coal, iron, and railroads. Most famously, it became known for shipbuilding and banking. Glasgow was the heart of Scotland's economy.

After the First World War in 1918, Scotland's economy started to decline. Thousands of well-paying engineering jobs were lost, and unemployment was very high, especially in the 1930s. Demand during the Second World War helped for a while, but times were tough in the 1950s and 1960s.

The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s brought new wealth. This led to a new cycle of economic ups and downs, even as the old industries faded away.

Contents

How did Scotland's economy begin?

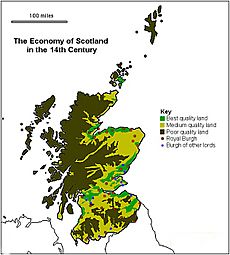

Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales. However, it has much less good land for farming or raising animals. This meant that farming on less fertile land and fishing were very important in early times. Scotland has a huge coastline, about 4,000 miles long, which is great for fishing.

Scotland also gets a lot of rain. This helped create large areas of peat bog, which is acidic. Combined with strong winds and salt spray, this made most of the islands treeless. Hills, mountains, and marshes made it very hard to travel or conquer land within Scotland.

The first known settlements were from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. Archaeologists found a camp near Biggar from around 8500 BC. Later, Neolithic farming brought permanent homes. The well-preserved stone house at Knap of Howar on Papa Westray dates from 3500 BC. This is about 500 years older than the famous village of Skara Brae on Orkney.

Around 2000 BC, during the Bronze Age, fewer large stone buildings were built. Studies of pollen show that forests grew more, and less land was farmed. Metalworking with bronze and iron slowly came to Scotland from Europe. Scotland's population grew to about 300,000 people in the second millennium BC.

The Romans, led by Gnaeus Julius Agricola, entered Scotland in 79 AD. They even sent ships around the coast to the Orkney Islands. A geographer named Ptolemy listed 19 "towns" based on Roman information. However, no real cities have been found from this time. These "towns" might have been hill forts or temporary market places. For about 300 years, Rome had some presence along Scotland's southern border.

What was the economy like in the Middle Ages?

Early Middle Ages (around 500-1000 AD)

The early Middle Ages saw colder temperatures and more rain. This made some land less productive. Scotland didn't have big cities like other parts of Britain had under the Romans. So, its economy was almost entirely based on farming.

Because there weren't good transport links or large markets, most farms had to produce all their own food. This included meat, dairy, and grains. People also gathered food and hunted. Early farms were usually a single home or a small group of three or four homes. Each probably held a family.

Farming used a system where crops were grown every year in an "infield" near the settlement. An "outfield" further away was used for crops in some years and left empty in others. This system continued until the 1700s. Bones found show that cattle were the most important animals, followed by pigs, sheep, and goats. Imported goods like pottery and glass have been found.

High Middle Ages (around 1000-1300 AD)

Farming and local trade still dominated Scotland's economy. But there was more foreign trade and wealth gained from military victories. By the end of this period, coins started to replace bartering (trading goods directly).

Most of Scotland's wealth came from raising animals, not just growing crops. Crop farming grew a lot during the "Norman period." Low-lying areas had more crop farming than high-lying areas like the Highlands or Galloway. Galloway was famous for its cattle.

A typical farmer might have used about 26 acres of land. People in Scotland who spoke Gaelic often preferred raising animals. They were happy to give land to French and English-speaking settlers, but held onto their higher lands. This might have led to the split between the Highlands/Galloway and the Lowlands later on.

The main land measurement unit was the davoch, or "Scottish ploughgate." It might have been about 104 acres. Cattle, pigs, and cheeses were common foods. But many other things were produced, like sheep, fish, rye, barley, beeswax, and honey.

Before King David I, Scotland didn't have known chartered towns called burghs. Most burghs already existed, but David I gave them legal status. He copied the rules for burghs from English towns like Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Early residents of burghs were often from Flanders, England, France, and Germany, not Gaelic Scots. The words used for burghs were mostly Germanic or French.

Late Middle Ages (around 1300-1500 AD)

Travel was hard due to rough land and poor roads. So, there was little trade between different parts of the country. Most settlements relied on what they produced locally. Farms were often small groups of families who worked the land together. They usually farmed strips of land called run rigs, which ran downhill to include both wet and dry areas. This helped with extreme weather.

Most plowing was done with a heavy wooden plow pulled by oxen. Farmers often had to provide oxen to plow their lord's land and grind their grain at the lord's mill. The rural economy seemed to do well in the 1200s. Even after the Black Death, it was still strong. But by the 1360s, incomes dropped by a third to half. They slowly recovered in the 1400s.

Most of Scotland's towns were on the east coast. These included Aberdeen, Perth, and Edinburgh, which grew thanks to trade with Europe. In the southwest, Glasgow started to grow. Ayr and Kirkcudbright sometimes traded with Spain and France.

The wool trade was a big export early in this period. But a disease called sheep-scab hurt the trade, and it declined from the early 1400s. Unlike England, Scotland didn't start making a lot of cloth. Only rough, low-quality cloths were important.

Scotland had few developed crafts. By the late 1400s, a native iron casting industry began, making cannons. Silver and goldsmithing also started. As a result, Scotland mostly exported raw materials like wool, hides, salt, fish, animals, and coal. Scotland often lacked wood, iron, and grain in bad harvest years. Exports of hides and salmon did better than wool.

The desire for luxury goods, which had to be imported, led to a shortage of bullion (gold and silver). This, and money problems for the king, led to the value of coins being cut. The amount of silver in a penny was cut to almost a fifth between the late 1300s and late 1400s.

What happened in the early modern era?

1500s

From the mid-1500s, demand for Scottish cloth and wool in Europe dropped. Scots responded by selling more traditional goods like salt, herring, and coal. The late 1500s were tough economically, made worse by more taxes and currency losing value. In 1582, a pound of silver was worth 640 shillings. By 1601, it was 960 shillings. Wages rose quickly but didn't keep up with rising prices.

There were frequent harvest failures. Almost half the years in the late 1500s saw food shortages, requiring grain to be brought in from other countries. Outbreaks of plague also caused problems. Some industries began, often using foreign experts. For example, a Venetian helped develop glass blowing. George Bruce of Carnock used German methods to solve drainage issues in his coal mine at Culross. In 1596, the Society of Brewer's was set up in Edinburgh, and English hops allowed Scottish beer to be brewed.

1600s

In the early 1600s, famine was common. The invasions of the 1640s greatly impacted Scotland's economy. Crops were destroyed, and markets were disrupted, leading to rapid price increases. Under the Commonwealth, Scotland was highly taxed but gained access to English markets.

After the king was restored, the border with England was re-established, along with customs duties. Economic conditions were generally good from 1660 to 1688. Landowners improved farming and cattle raising. The royal burghs' monopoly on foreign trade ended in 1672. They kept control of luxury goods like wines and silks, but trade in salt, coal, corn, and hides opened up.

The English Navigation Acts limited Scotland's trade with England's colonies. But Scots often found ways around these rules. Glasgow became an important trading center, trading with American colonies. They imported sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia. Exports included linen, wool, coal, and grindstones. English tariffs on salt and cattle were harder to avoid.

By the end of the century, drovers roads were well-established. These roads stretched from the Highlands through southwest Scotland to northeast England, used to move cattle. Scottish attempts to use their own tariffs didn't work well because Scotland had few vital exports to protect. Attempts to build luxury industries like cloth mills and soap works were mostly unsuccessful.

The late 1600s saw good economic times end. Trade with the Baltic and France slumped from 1689 to 1691 due to French protectionism and changes in the Scottish cattle trade. This was followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696, 1698-9), known as the "seven ill years." This caused severe famine and a drop in population, especially in the north.

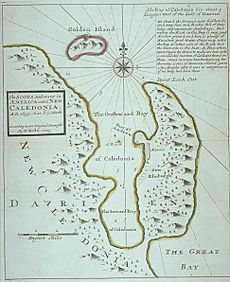

The Scottish Parliament in 1695 made plans to help the economy. This included setting up the Bank of Scotland. The "Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies" was formed to raise money. This company invested in the Darien scheme. This was a big plan by William Paterson, who founded the Bank of England. He wanted to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama to trade with the Far East.

Merchants and landowners in Edinburgh didn't have enough money, so the company asked ordinary people for funds. People responded with great national pride. But the project was a disaster. Only one ship and 1,000 colonists returned home. The cost of £150,000 put a huge strain on Scotland's economy.

How did the economy change in the 1700s?

By the early 1700s, joining with England seemed like a good idea for Scotland. It promised access to England's much larger markets and those of the growing British Empire. The Scottish parliament voted on January 6, 1707, to accept the Treaty of Union. This was a full economic union. Most of its 25 articles dealt with how the new state, "Great Britain," would handle money and trade.

Scotland gained 45 members in the House of Commons and 16 in the House of Lords. The Scottish parliament ended. Scotland's currency, taxes, and trade laws were replaced by those made in London. At the time, England had about five times Scotland's population and 36 times its wealth.

Farming improvements

Contact with England led to efforts to improve farming among the wealthy. New methods were introduced, like haymaking, English plows, and foreign grasses. Turnips and cabbages were grown, lands were fenced, and marshes were drained. Roads were built, and trees were planted. Crop rotation was also introduced. The potato came to Scotland in 1739, greatly improving the diet of poor farmers.

The old "runrig" system of farming began to be replaced by enclosed fields. The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, with 300 members including dukes and landlords. The Lothians became a major grain area, Ayrshire for cattle, and the Borders for sheep. However, while some landowners helped displaced workers, enclosures also led to unemployment and forced people to move to towns or abroad.

Exports and trade

The economic benefits of the union appeared very slowly. Scotland was too poor to take advantage of the bigger free market. By 1750, some progress was visible. Sales of linen and cattle to England increased. Money came from military service, and the tobacco trade, dominated by Glasgow after 1740, grew.

However, Glasgow mostly re-exported the tobacco, so it didn't boost local businesses much. The tobacco trade collapsed during the American Revolution when supplies were cut off. A new important trade with the West Indies developed, making up for the loss of tobacco. The Scottish Enlightenment, a period of great intellectual growth, was helped by the union. But it didn't directly benefit the economy much. Scotland in 1700 was a poor farming society with 1.3 million people. Its quick transformation into a rich industrial leader was unexpected.

Glasgow's rise

In Glasgow, merchants who made money from the American trade between 1730 and 1790 started investing in other industries. These included leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks. This laid the groundwork for Glasgow to become a leading industrial center after 1815.

At first, Glasgow used hired ships. By 1736, it had 67 of its own ships, with a third trading with the New World. Glasgow became the center of the tobacco trade, especially re-exporting to France. The wealthy merchants in this business became known as the tobacco lords. They controlled the city for most of the century.

By 1790, trade with the West Indies grew, reflecting the cotton industry's growth, Britain's love for sweets, and the West Indies' demand for herring and linen. Between 1750 and 1815, 78 Glasgow merchants imported sugar, cotton, and rum. They also bought West Indian plantations, Scottish estates, or cotton mills.

Other towns also benefited. Greenock expanded its port in 1710 and sent its first ship to the Americas in 1719. It soon became important for importing sugar and rum.

Linen industry

The linen industry was Scotland's most important industry in the 1700s. It formed the basis for later cotton, jute, and wool industries. Scottish members of parliament prevented a tax on linen exports. From 1727, it received government money, leading to a big expansion of trade. Paisley adopted Dutch methods and became a major production center. Glasgow made linen for export, and this trade doubled between 1725 and 1738.

Scottish industrial policy was guided by the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland. They wanted to build an economy that worked with England's, not against it. Since England had woolens, Scotland focused on linen. With encouragement and money from the Board, Scottish linen entrepreneurs became dominant and increased their market share, especially in the American colonies.

What was the 1800s like?

Scotland's population grew steadily in the 1800s. It went from 1,608,000 in 1801 to 4,472,000 in 1901. The economy, which had long been based on farming, started to industrialize after 1790. At first, the main industry in the west was cotton spinning and weaving. But in 1861, the American Civil War cut off raw cotton supplies, and the industry never fully recovered.

Thanks to many skilled business people and engineers, and its large supply of easily mined coal, Scotland became a world leader in engineering, shipbuilding, and making locomotives. Steel replaced iron after 1870.

Liberal ideas grew in Scottish cities. The belief in free trade and strong individualism of business owners combined with a focus on education and self-reliance. These unique liberal values remained strong, even with political challenges by the 1900s.

Banking system

The first Scottish banks, Bank of Scotland (1695) and the Royal Bank of Scotland (1727), are still operating today. By the early 1800s, Glasgow also had strong banks, and Scotland had a thriving financial system. There were over 400 bank branches, which was twice the level in England. Scottish banks were less strictly regulated than English ones. Historians often say that the flexible Scottish banking system helped the economy grow quickly in the 1800s.

The British Linen Company, started in 1746, was the biggest linen company in Scotland in the 1700s. It exported linen to England and America. It could raise money by issuing promissory notes. These notes worked like bank notes, and the company slowly moved into lending money to other linen makers. By the early 1770s, banking became its main business. Renamed British Linen Bank in 1906, it was one of Scotland's top banks until the Bank of Scotland bought it in 1969.

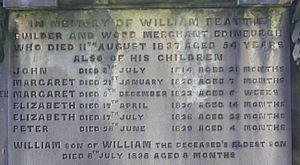

Emigration (people leaving Scotland)

Even with industry growing, there weren't always enough good jobs. So, between 1841 and 1931, about 2 million Scots moved to North America and Australia. Another 750,000 moved to England. By the 2000s, there were about as many people of Scottish descent in Canada and the U.S. as the 5 million people still living in Scotland.

The Industrial Revolution

During the Industrial Revolution, Scotland became a major commercial, intellectual, and industrial center of the British Empire. Around 1790, the most important industry in western Scotland became textiles, especially cotton. This industry thrived until the American Civil War in 1861 cut off raw cotton supplies.

However, by then, Scotland had developed heavy industries using its coal and iron. The invention of the hot blast for smelting iron (1828) changed the Scottish iron industry. Scotland became a center for engineering, shipbuilding, and making locomotives. By the late 1800s, steel production largely replaced iron. Andrew Carnegie, an emigrant from Scotland, built the American steel industry and gave a lot of his money to Scotland.

Growing cities

As the 1800s went on, Lowland Scotland focused more and more on heavy industry. Glasgow and the River Clyde became a major shipbuilding center. Glasgow grew into one of the world's largest cities, known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.

These industrial developments brought work and wealth. But they happened so fast that housing, town planning, and public health services couldn't keep up. For a while, living conditions in some towns and cities were very bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and rising rates of tuberculosis.

Dundee's industries

Dundee improved its harbor and became an industrial and trading center. Dundee's industrial history was based on "the three Js": jute, jam, and journalism. East-central Scotland became very reliant on linens, hemp, and jute. Despite ups and downs in trade, profits were good in the 1800s. Companies were typically family-owned. The profits helped make Dundee an important source of overseas investment, especially in North America. However, these profits were rarely invested locally, except in the linen trade. This was because low wages limited local spending, and there were no important natural resources. So, the Dundee region offered few chances for new industries.

Coal mining

Coal mining became a major industry and continued to grow into the 1900s. It produced fuel to heat homes, power factories, and run steam engines, locomotives, and steamships. By 1914, there were 1,000,000 coal miners in Scotland. Miners' lives were similar to those everywhere, with a strong focus on masculinity, equality, group loyalty, and support for workers' rights.

Railways

Britain was the world leader in building railways and using them to expand trade and coal supplies. The first line opened in 1831. By the late 1840s, there was good passenger service. An excellent network of freight lines reduced the cost of shipping coal. This made products made in Scotland competitive throughout Britain. For example, railways opened the London market to Scottish beef and milk. They helped the Aberdeen Angus become a famous cattle breed worldwide.

Shipbuilding on the Clyde

Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the River Clyde through Glasgow) reached its peak between 1900 and 1918. In 1913, 370 ships were completed, and even more during the First World War. Over 25,000 ships were built by about 300 different companies over time.

The first small shipyards opened in 1712 at the Scott family's shipyard in Greenock. After 1860, the Clydeside shipyards specialized in steamships made of iron (and later steel). These quickly replaced wooden sailing ships for both merchant and navy fleets around the world. The Clyde became the world's top shipbuilding center. "Clydebuilt" became a mark of quality. The shipyards received contracts for warships and famous liners like the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth 2.

Major companies included Denny of Dumbarton, Scotts of Greenock, Lithgows of Port Glasgow, and Fairfield of Govan. Equally important were the engineering firms that supplied the engines, boilers, and steering gear for these ships. The biggest customer was Sir William Mackinnon, who ran five shipping companies from Glasgow in the 1800s.

A good example of a Glasgow business owner was William Lithgow (1854–1908). At 16, he inherited £1,000, and by his death, he left £1.75 million. He used new designs and ideas, like interchangeable parts. He also helped finance his customers by buying shares in their ships and constantly expanded his shipyard. When rivals went bankrupt in the 1880s and 1890s, Lithgows survived. His children and grandchildren built the company into the world's largest private shipbuilding firm by 1950. However, the family sold the shipyards to the government in 1977 and invested in other industries.

The companies attracted workers from rural areas and immigrants from Catholic Ireland. They offered inexpensive company housing, which was a big improvement from inner-city slums. This led many owners to support government housing programs and self-help projects for working-class families.

Rural life and the Highlands

A few powerful families, like the dukes of Argyll and Sutherland, owned the best lands and controlled local politics and economy. As late as 1878, 68 families owned almost half the land.

Farming in the Lowlands steadily improved after 1700. However, after the Corn Laws were removed in 1846, Britain adopted free trade. Grain imports from America made crop production less profitable. This led to a continuous movement of people from the land to cities or further afield to England, Canada, America, or Australia.

The traditional landowners kept their political power, even as urban middle classes grew. Electoral reforms in Scotland were less far-reaching than in England. Landowners managed to keep political power tilted in their favor.

Meanwhile, the Highlands were very poor and traditional. They had little connection to the Scottish Enlightenment or the Industrial Revolution. The wealthiest landlords needed cash to maintain their status in London society. They also needed fewer soldiers now that wars had lessened. So, they started demanding money rents, displacing farmers to raise sheep, and reducing the traditional clan relationships.

A new group appeared, the crofters. These were poor families living on very small rented farms used to grow potatoes. They also made money from kelping (burning seaweed for ashes), fishing, spinning linen, and military service.

The Napoleonic Wars (1790–1815) brought good times to the Highlands. The economy grew thanks to wages from kelping, fisheries, weaving, and large projects like the Caledonian Canal. On the East Coast, farmlands improved, and high cattle prices brought money. Serving in the Army was also attractive to young men from the Highlands, who sent money home and retired there with their pensions.

The good times ended after 1815. Long-term negative factors began to hurt the economic position of the poor tenant farmers, or "crofters." Landowners adopted a market-focused approach after 1750. This broke down the traditional social and economic structure of the northwest Highlands and Hebrides Islands, causing great disruption for the crofters. The Highland Clearances and the end of the township system followed changes in land ownership and the replacement of cattle with sheep.

What happened in the 1900s?

Trade unions

Scottish workers played a big role in the industrial strikes across Britain from 1910-14. The National Sailors' and Firemen's Union led strikes in many port cities. Activists in the Glasgow Trades Council took the lead locally. The strong local nature of the strike movement in Glasgow made the strikes more unified there. It also shaped how waterfront organizations developed on the Clyde, with independent local unions forming for dockers and seamen.

Shipbuilding decline

Before 1914, Clydeside shipyards were the busiest in the world, producing over a third of all British ships. They expanded greatly during the First World War, mainly to build transport ships that German submarines were sinking. Companies were confident of growth after the war, so they borrowed a lot to expand their facilities.

But after the war, jobs dropped as the shipyards became too big, too expensive, and not efficient enough. World demand was also down. The most skilled workers were hit hard because their specialized skills had few other uses. A major weakness was a delay in developing new technologies like turbine engines, diesel engines, and welding techniques. The shipyards went into a long period of decline, only briefly interrupted by the Second World War's temporary expansion. In the 2000s, only a few shipyards remain active.

Fishing industry

The years before the First World War were the best for inshore fisheries. Aberdeen was the main port. Fish landings reached new highs, and Scottish catches dominated Europe's herring trade, making up a third of the British catch. In 1911, 34,000 men worked on boats, and another 50,000 women worked part-time on shore processing fish.

High productivity came from switching to more efficient steam-powered boats. Scotland's fishermen had almost a thousand steam drifters by 1914, worth over two million pounds. However, the rising cost of equipment meant they needed new sources of money, mainly from merchants and fish salesmen. Fishermen now had to share their profits and got caught in informal contracts and debts.

Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization happened quickly in the 1970s and 1980s. Most of the traditional industries shrank drastically or closed down completely. A new service-oriented economy emerged to replace the old heavy industries.

North Sea oil

Since the Second World War, Scotland's economy has been fully integrated into the overall British economy. The most unique feature has been the discovery of oil offshore in the North Sea. The oil brought new wealth and new people to even the most isolated areas.

The discovery of the giant Forties oilfield in October 1970 was the first sign that Scotland would become a major oil-producing nation. This was confirmed when Shell Expro found the huge Brent oilfield east of Shetland the next year. Oil production started from the Argyll field in June 1975, followed by Forties in November of that year.

John Brown & Company's shipyard at Clydebank changed from a traditional shipbuilding business to a company in the high-tech offshore oil and gas drilling industry. After 1972, the firm was owned by three multinational corporations. Its adaptation to drilling was affected by changing international markets and technologies. Employment in the yard is now much lower.

Images for kids

-

The RMS Queen Mary was built in Glasgow at the John Brown & Company shipyard.

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |