Economy of Scotland in the Middle Ages facts for kids

The economy of Scotland in the Middle Ages was all about how people made a living in Scotland from the early 400s to the early 1500s. This included farming, making things by hand, and trading goods. Scotland has a lot of coastline, but not much good farmland compared to England. Because of this, farming animals and fishing were super important parts of the economy back then. In the early Middle Ages, it was hard to travel, so most towns and farms had to produce almost everything they needed themselves. Most farms were run by families and used a special system called infield and outfield farming.

Farming grew a lot in the High Middle Ages (around 1000-1300 AD). Agriculture actually did quite well from the 1200s to the late 1400s. Unlike England, Scotland didn't have any towns left over from Roman times. But from the 1100s, new towns called burghs started to appear. These were special towns given legal rights by the king, and they became big centers for crafts and trade. Scotland also started making its own coins, but English money was probably used more often. For a long time, people mostly traded goods directly (this is called bartering) instead of using money. Making things and industries didn't really grow much until the end of the Middle Ages. Even though Scotland traded with many places, it mostly sold raw materials like wool. In return, it bought more and more fancy goods. This led to a shortage of silver and gold (called bullion) and might have caused money problems in the 1400s.

Contents

Scotland's Land and People

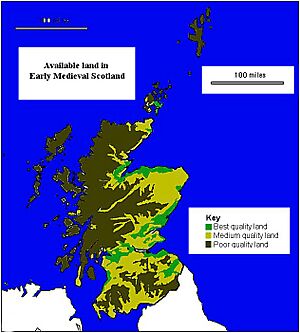

Scotland is about half the size of England and Wales. It has a lot of coastline, but only a small amount of good land for farming or raising animals. Most of this good land is in the south and east. This meant that raising animals on less fertile land and fishing were super important for the economy long ago. Scotland gets a lot of rain because it's in the North Atlantic. This rain created many peat bogs, which are acidic and made many western islands treeless. Hills, mountains, and marshes made it really hard to travel or conquer different parts of the country.

After the Romans left Britain in the 400s, four main groups lived in what is now Scotland. The Picts were in the east, the Gaelic-speaking people (Scots) from Dál Riata were in the west, the Britons were in the south, and the Angles were in the southeast. This changed when fierce Vikings started raiding in the 700s. The Vikings took over Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles. These threats might have helped the Picts and Gaels to join together. This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s. He became the leader of a combined Gaelic-Pictish kingdom, which was first called Kingdom of Alba and later became Scotland.

From the 500s, Christianity slowly spread across Scotland. It's thought that missionaries from Ireland and Scotland, like St Columba, helped with this. However, historians now think that Christianity probably spread more gradually through trade, conquests, and marriages.

It's hard to know exactly how many people lived in Scotland during the Middle Ages because there are almost no written records. Before the Black Death arrived in 1349, the population might have grown from half a million to a million people. The Black Death was a terrible plague that killed many people. If Scotland was like England, its population might have dropped to as low as half a million by the end of the 1400s.

Farming in Medieval Scotland

In the early Middle Ages, it was difficult to transport goods. This meant that small settlements had to produce almost everything they needed themselves. Scotland didn't have big towns like other parts of Britain, so its economy was mostly based on farming. Without good roads or large markets, most farms had to grow their own food, raise animals for meat and milk, and gather wild plants.

Archaeological finds show that farming was done on single farms or in small groups of three or four homes. Each home probably had a single family. Neighbors were often related, as land was passed down through families. Farmers used a system with an "infield" close to the homes, where crops were grown every year. Further away was the "outfield," where crops were grown some years and then left empty (fallow) in others to help the soil recover. This system was used until the 1700s.

The type of farming depended on the land and weather. Because it was cold and wet, farmers grew more oats and barley than wheat. Bones found by archaeologists show that cattle were the most important farm animals, followed by pigs, sheep, and goats. Chickens and other domestic fowl were rare. Around the year 1000, fishing became much more important. This increase in fishing in the Highlands and Islands might have happened because Scandinavian settlers arrived there.

The early Middle Ages saw a change in climate, with colder temperatures and more rain. This made some land less productive. However, from about 1150 to 1300, the weather improved with warm, dry summers and milder winters. This allowed farming to happen in higher places and made the land more productive. Crop farming grew a lot, especially in low-lying areas.

Most farming happened on small settlements called fermtouns in the lowlands or bailes in the Highlands. These were groups of a few families who worked together on an area of land. This land was usually divided into long strips called run rigs, which were given to tenant farmers. These strips often ran downhill, so they included both wet and dry land. This helped farmers deal with extreme weather. Most plowing was done with heavy wooden plows that had iron blades, pulled by oxen. Oxen were good for heavy soil and cheaper to feed than horses. Farmers often had to use their oxen to plow the lord's land and grind their grain at the lord's mill, which they didn't like.

In the late Middle Ages (after 1300), temperatures started to drop again, and it became wetter. This limited how much land could be used for growing crops, especially in the Highlands. New religious groups, like the Cistercians, brought new farming ideas. Their monasteries owned a lot of land, especially in the Borders region. They were big sheep farmers and produced wool to sell in places like Flanders. By the late Middle Ages, Melrose Abbey and the Earl of Douglas each had about 15,000 sheep, making them some of the biggest sheep farmers in Europe.

Monasteries organized their farming into "granges." These were farms run by lay brothers (people who lived like monks but weren't priests). Granges were usually close enough to the main monastery so the workers could go back for church services. They were used for raising animals, growing crops, and even some early industry. The rural economy seemed to do very well in the 1200s. Even after the Black Death arrived in Scotland in 1349, it was still strong for a while. However, by the 1360s, incomes dropped by a third to half, before slowly recovering in the 1400s.

Scottish Towns (Burghs)

Records of burghs, which were small towns given special legal rights by the king, can be found from the 1000s. The word "burgh" comes from a Germanic word for a fortress. These towns grew quickly during the time of King David I (1124–53). Before this, Scotland didn't really have any identifiable towns. Most of the burghs that King David gave charters to probably already existed as small settlements. The charters (official documents) were almost exact copies of those used in England. The first citizens of these burghs, called burgesses, were often English or Flemish. They could charge fees and fines to traders in the area around their town.

Most of the early burghs were on the east coast. These included the largest and richest ones like Aberdeen, Berwick, Perth, and Edinburgh. Their growth was helped by trade with Europe. In the southwest, towns like Glasgow, Ayr, and Kirkcudbright benefited from sea trade with Ireland, and a bit with France and Spain.

Burghs had their own special layouts and economic jobs. They usually had a fence or a castle around them. They also had a marketplace, often a wide main street or a crossroads, marked by a market cross. Houses for the burgesses and other people were nearby. About 15 burghs were started during King David I's reign, and by 1296, there were 55 burghs. Besides the main royal burghs, many smaller burghs were created by local lords or churches in the late Middle Ages. Most of these were much smaller than the royal ones. They couldn't trade internationally, so they mainly served as local markets and places for craftspeople. In general, burghs probably traded much more with their local areas than nationally or internationally, relying on nearby farms for food and raw materials.

Making Goods and Trading

Burghs were centers for basic crafts. People made shoes, clothes, dishes, pots, wooden items, bread, and ale. These were usually sold to local people and visitors on market days. However, Scotland didn't have many developed industries for most of this period. By the late 1400s, Scotland started to have its own iron-casting industry, which led to making cannons. The country also became known for its silver and goldsmiths later on.

Because of this, Scotland's most important exports were raw materials that hadn't been processed much. These included wool, animal hides, salt, fish, animals, and coal. Scotland often needed to import wood, iron, and, in years of bad harvests, grain. Grain was imported in large amounts, especially from ports in the Baltic Sea, through Berwick and Ayr.

Limited information from the early Middle Ages suggests that Scotland traded some luxury goods with Europe. For most of the period, we don't have detailed customs records like England does. The first records for Scotland only start in the 1320s. In the early Middle Ages, as Christianity grew, wine and precious metals were imported for church ceremonies. There are also a few stories about trips to and from other countries. For example, Adomnán wrote about St Columba waiting at a port for ships bringing news, and probably other things, from Italy. Imported items found at old sites include pottery and glass. Many sites also show signs of iron and precious metal working.

In the High Middle Ages, even though farming and local trade were still most important, foreign trade increased. Coins started to replace bartering. Scottish coins were first made during the reign of King David I. Mints (places where coins are made) were set up in Berwick, Roxburgh, Edinburgh, and Perth. But until the end of the Middle Ages, most trading was done without metal money, and English coins were probably more common than Scottish ones.

Before the Wars of Scottish Independence started in the early 1300s, most sea trade was probably along the coast, and most foreign trade was with England. The wars closed English markets and led to more piracy and problems for sea trade on both sides. This might have led to more trade with Europe. Early records from the 1330s show that Scottish merchants handled five-sixths of this trade.

Wool and hides (animal skins) were the main exports in the late Middle Ages. From 1327 to 1332, Scotland exported about 5,700 sacks of wool and 36,100 leather hides each year. The Wars of Independence hurt trade and damaged farmland, so these numbers fell. However, trade recovered and reached a peak in the 1370s, with an average of 7,360 sacks of wool exported each year. But a worldwide economic slowdown from the 1380s caused exports to drop again. A disease called sheep-scab also seriously hurt the wool trade from the early 1400s. Unlike England, Scotland didn't start making a lot of cloth. Only rough, poor-quality cloths seemed to be important.

Exports of hides and especially cod fish held up much better than wool. Scotland had a big advantage in the quality of its cod. Hide exports averaged 56,400 a year from 1380 to 1384. In the late Middle Ages, the king, lords, church leaders, and rich merchants wanted more luxury goods. These goods, like fine cloth from Flanders and Italy, mostly had to be imported. This led to a constant shortage of silver and gold (bullion). This problem, along with money troubles for the king, caused the value of Scottish coins to be lowered several times. The amount of silver in a penny was cut to almost a fifth between the late 1300s and late 1400s. A heavily devalued "black money" coin was introduced in 1480 but had to be taken out of circulation two years later. This might have helped cause money and political problems.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |