Vikings facts for kids

The Vikings were a brave seafaring people who originally came from Scandinavia. This area is now made up of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. From the late 700s to the late 1000s, Vikings explored, traded, and settled in many parts of Europe. They traveled very far, reaching places like the Mediterranean Sea, North Africa, the Middle East, Greenland, and even Vinland (which is now Newfoundland in Canada, North America).

This time of great activity is known as the Viking Age. During this period, the term "Viking" often refers to all the people living in Scandinavia. The Vikings had a big impact on the early history of Northern Europe and Eastern Europe. They helped shape the political and social life of England and parts of France. They also helped start the first East Slavic state called Kievan Rus.

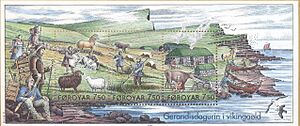

Vikings were excellent sailors and knew how to navigate their special longships. They created Norse settlements and governments in the British Isles, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Greenland, Normandy, and along the Baltic Sea coast. They also traveled along the Dnieper and Volga trade routes in Eastern Europe, where they were known as Varangians. Groups like the Normans, Norse-Gaels, Rus, Faroese, and Icelanders came from these Norse settlements. Some Rus Vikings even traveled south to Constantinople, a big city in the Byzantine Empire. Vikings also reached the Caspian Sea and Arabia. They were the first Europeans to reach North America, briefly settling in Newfoundland (Vinland).

As they spread Norse culture, they also brought back new ideas and influences to Scandinavia. This affected the history and even the genes of people in both places. During the Viking Age, the smaller kingdoms in Scandinavia slowly joined together to form the three larger kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

The Vikings spoke Old Norse and wrote using runes. For most of the Viking Age, they followed the Old Norse religion. However, between the 700s and 1100s, they gradually became Christians. Vikings had their own laws, art, and architecture. Most Vikings were also farmers, fishermen, craftspeople, and traders. What people often imagine about Vikings today is sometimes different from the real, complex civilization found through archaeology and old writings. A romantic idea of Vikings as brave adventurers started in the 1700s and became very popular in the 1800s during the Viking revival. Modern ideas about Vikings often use stereotypes, like the idea that they wore horned helmets, which is not true.

Contents

- What Does the Word "Viking" Mean?

- Viking History and Times

- Viking Culture and Daily Life

- Viking Weapons and Warfare

- Viking Trade and Economy

- The Viking Legacy

- Viking Genetic Legacy

- Related Pages

- See also

What Does the Word "Viking" Mean?

The exact meaning of the word Viking has been discussed a lot by experts. One idea is that it comes from an old English word, wicing, which meant 'settlement'. Another idea, less popular, is that it came from an Old Norse word, vík, meaning 'creek' or 'small bay'.

A more recent idea suggests that Viking comes from an Old Norse word, vika, meaning 'sea mile'. This might have referred to the distance rowers traveled before changing shifts. This idea fits better with language studies and suggests the term might be older than when Vikings started using sails.

In the Middle Ages, viking came to mean Scandinavian pirates or raiders. The earliest English writings using the word wicing were around 700 AD, before the first known Viking attack in England. These writings translated wicing as 'pirate'. In Old English poems, the word wicing was used, but it didn't mean a nationality. Other words like Northmen or Danes were used for that.

The word Viking became popular in modern English in the 1700s. At that time, it started to mean a heroic "barbarian warrior." In the 1900s, the meaning grew to include not just the raiders, but any person from the Scandinavian culture during the Viking Age (late 700s to mid-1000s). As an adjective, "Viking" is used for anything related to these people and their culture, like Viking age or Viking ship.

Viking History and Times

The Viking Age: A Time of Exploration

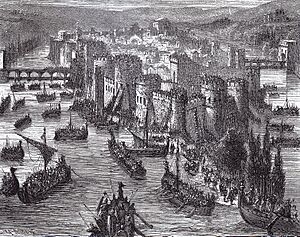

The Viking Age in Scandinavia lasted from the first recorded raids in 793 AD until the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Vikings used the Norwegian Sea and Baltic Sea to travel south.

The Normans were descendants of Vikings who had settled in northern France in the 900s. They continued to have a strong influence in northern Europe. Even King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, had Danish Viking ancestors. Two Vikings, Sweyn Forkbeard and his son Cnut the Great, even became kings of England.

During the Viking Age, Vikings explored and settled in many places. This included their homelands in modern Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. They also settled in the Danelaw in England, which included places like York. Viking sailors found new lands to the north, west, and east. They founded settlements in the Shetland, Orkney, and Faroe Islands, as well as Iceland and Greenland. Around 1000 AD, they briefly settled at L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. The Greenland settlement was started around 980 AD, but it ended by the mid-1400s, possibly due to climate changes.

A legendary Viking leader named Rurik is said to have taken control of Novgorod in (modern Russia) in 862 AD. His relative Oleg captured Kiev in 882 AD and made it the capital of the Rus. The Rurik dynasty ruled Russia until 1598.

As early as 839 AD, Scandinavians worked as soldiers for the Byzantine Empire. In the late 900s, a special group of imperial bodyguards was formed, known as the Varangian Guard. Many Scandinavians joined this guard. Swedish men joined the Varangian Guard in such large numbers that a medieval Swedish law tried to stop them from leaving.

Archaeological finds show that Vikings reached Baghdad, the center of the Islamic Empire. The Norse regularly traveled the Volga River to trade goods like furs, tusks, and slaves. Important trading towns during this time included Birka, Hedeby, Kaupang, Jorvik, Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod, and Kiev.

Scandinavian Norsemen explored Europe by sea and river for trade, raids, settlement, and conquest. They settled in places like the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norse Greenland, Newfoundland, the Netherlands, Germany, Normandy, Italy, Scotland, England, Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Russia, and Turkey. Their actions also led to the formation of the modern Scandinavian countries.

During the Viking Age, the countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark did not exist as they do today. However, the people living in these areas were very similar in culture and language. We only know the names of Scandinavian kings reliably from the later part of the Viking Age. After this period, the separate kingdoms slowly became distinct nations, which happened as they became Christian. So, the end of the Viking Age also marked the beginning of their Middle Ages.

Slavic and Viking groups were often connected. They sometimes fought, but also mixed and traded with each other. In the Middle Ages, goods moved from Slavic areas to Scandinavia. Denmark was a place where Slavic and Scandinavian cultures blended. Experts believe that the presence of Slavs in Scandinavia was more important than once thought.

A 10th-century grave of a female warrior in Denmark was first thought to be Viking. But a 2019 study suggested she might have been a Slav from modern Poland. The first king of the Swedes, Eric, was married to Gunhild, who was from a Polish royal family. His son, Olof, had a Slavic partner named Edla. They had a son, Emund the Old, who became King of Sweden, and a daughter, Astrid, who became Queen of Norway. Cnut the Great, who was King of Denmark, England, and Norway, was the son of a daughter of Mieszko I of Poland.

Viking Expansion Across Lands

Norwegian Vikings began settling Iceland in the 800s. The first mention of Iceland and Greenland in official writings was in a letter from the Pope in 1053. Later, after these islands became Christian, their own histories were written down in sagas. Vikings explored the northern islands and coasts of the North Atlantic. They also ventured south to North Africa and brought people from the Baltic coast and European Russia for trade.

They raided, traded, worked as soldiers, and set up settlements over a large area. Early Vikings likely returned home after their raids. Later, they began to settle in other lands permanently. Vikings led by Leif Erikson reached North America. They set up short-lived settlements in what is now L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada. This expansion happened during a time when the climate was warmer, known as the Medieval Warm Period.

Viking expansion into mainland Europe was limited. Their lands were next to powerful tribes to the south. Early on, the Saxons lived in what is now Northern Germany. The Saxons were strong and often fought with the Vikings. To protect themselves from the Saxons, the Danes built a huge defense wall called Danevirke near Hedeby.

The Vikings saw how Charlemagne violently forced the Saxons to become Christian during the Saxon Wars (772–804). The Saxons were defeated and their land became part of Charlemagne's empire. Fear of the Franks made the Vikings expand Danevirke even more. These defenses were used throughout the Viking Age and even until 1864.

The southern coast of the Baltic Sea was controlled by the Obotrites, Slavic tribes loyal to Charlemagne. In 808 AD, Vikings led by King Gudfred destroyed the Obotrite city of Reric. They moved the merchants and traders to Hedeby. This helped the Vikings become very powerful in the Baltic Sea throughout the Viking Age.

Because Vikings spread across Europe, studies of DNA and archaeology suggest that "Viking" might have become more of a "job description" than a family background for some groups.

Why Did the Vikings Expand?

The reasons why Vikings expanded are much debated. One idea is that they needed to find new resources and trade routes. They also took advantage of times when nearby regions were weak. For example, after Charlemagne's death, his empire broke into weaker parts, making England an easier target. England also had internal problems and many towns near the sea or rivers, which Vikings could easily reach.

The decline in old trade routes might also have played a role. Trade between Western Europe and other parts of Eurasia suffered after the Western Roman Empire fell in the 400s. The expansion of Islam in the 600s also affected trade with Western Europe.

Raids and settlements in Europe were not new, but Viking raids were the first to be well-documented by people who saw them. They were also much larger and happened more often than earlier raids. Vikings themselves were growing in numbers, and historians believe that a lack of resources or opportunities at home might have been a factor in their expansion.

Trading people for work was an important part of the Viking economy. Many of these people were taken to Scandinavia, but others were sold in eastern markets for silver or silk. The "Highway of Slaves" was a route Vikings used to travel from Scandinavia to Constantinople and Baghdad. With better ships in the 800s, Vikings could sail to Kievan Rus and northern Europe.

Jomsborg: A Legendary Stronghold

Jomsborg was a legendary Viking stronghold on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. It existed between the 960s and 1043. Its people were known as Jomsvikings. Jomsborg's exact location is still unknown, but it is thought to have been on the islands of the Oder river mouth.

The End of the Viking Age

While Vikings were active abroad, Scandinavia itself was changing. New influences arrived, and cultures shifted.

New Kingdoms and Economies

By the late 1000s, royal families, supported by the Catholic Church, gained more power. The three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden began to form. Towns appeared as centers for government, church, and markets. Money-based economies started to grow, similar to those in England and Germany. By this time, the flow of silver from the East had stopped, and English silver had also become less common.

Becoming Christian

Christianity became strong in Denmark and Norway in the 1000s. The new religion also began to organize itself more effectively in Sweden. Church leaders and local powerful people worked hard to spread Christianity. Old beliefs and ways of life began to change. By 1103, the first archbishopric (a church region led by an archbishop) was founded in Scandinavia, in Lund, Denmark.

As the new Scandinavian kingdoms joined the main Christian culture of Europe, the goals of their rulers changed. Their relationships with neighboring countries also changed.

One main way Vikings made money was by taking people from other European lands for work. The medieval Church believed that Christians should not own other Christians as workers. So, this practice became less common across northern Europe. This reduced the economic reason for raids, though some activity continued into the 1100s. Viking raids in Christian lands around the North and Irish Seas greatly decreased.

The kings of Norway continued to have power in parts of northern Britain and Ireland, and some raids continued into the 1100s. However, the military goals of Scandinavian rulers shifted. In 1107, Sigurd I of Norway sailed to the eastern Mediterranean with Norwegian crusaders to fight for the new Kingdom of Jerusalem. The kings of Denmark and Sweden also took part in the Baltic Crusades in the 1100s and 1200s.

Viking Culture and Daily Life

Many sources help us understand Viking culture, activities, and beliefs. Even though they didn't write many books, they had an alphabet and wrote about themselves on runestones. Most written information about Vikings comes from other cultures who met them. Since the mid-1900s, archaeological discoveries have given us a more complete picture of Viking life. Archaeology has shown us about their homes, crafts, ships, trade, and religious practices.

Viking Stories and Language

The most important original sources about Vikings are texts from Scandinavia and places where Vikings were active. Writing with Latin letters came to Scandinavia with Christianity. So, there are few native writings from Scandinavia before the late 1000s and early 1100s. Scandinavians did write short messages in runes. Most other writings about Vikings were made by Christian and Islamic people outside Scandinavia, often by those who had been affected by Viking raids.

Later writings about Vikings, like the Icelandic sagas, can also be important. These were written down in Iceland from the 1100s to 1300s. They tell many stories and traditions from the Viking Age. While we should be careful about taking these stories as exact history, they offer valuable details about Viking life, family histories, and values.

Vikings also left behind many Old Norse place names and words in areas they influenced. Some of these names are still used today, almost unchanged. They show us where Vikings settled and what places meant to them. Examples include Egilsay (Eigil's Island), Ormskirk (Orm's Church), and Vinland (Land of Wine). The Tynwald on the Isle of Man, a parliamentary body, also shows Viking influence.

Many common words in English come from the Old Norse language of the Vikings. This helps us understand their interactions with people in the British Isles. In the Shetland and Orkney Islands, Old Norse completely replaced local languages. It later became the extinct Norn language. Modern words and names like York (Horse Bay) and Swansea (Sveinn's Isle) also show Viking connections.

Language studies continue to provide important information about Viking culture, their social structure, and how they interacted with other people. Old Norse has had a big influence on modern Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Faroese, and Icelandic. However, Old Norse did not greatly influence Slavic languages in Eastern Europe. This might be because the languages were very different, and the Rus Vikings had more peaceful trade in those areas.

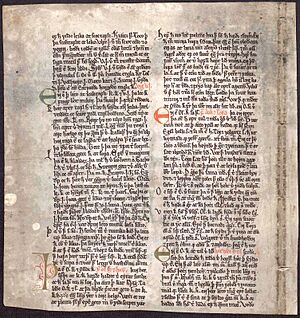

Runestones: Messages from the Past

The Norse people of the Viking Age could read and write using an alphabet called runor. While few runic writings on paper survive, thousands of stones with runic messages have been found where Vikings lived. These stones usually remember the dead, but are not always at graves. Runes were used until the 1400s, alongside the Latin alphabet.

Runestones are found in different numbers across Scandinavia. Denmark has about 250, Norway has 50, and Iceland has none. Sweden has between 1,700 and 2,500. The Swedish area of Uppland has the most, with 1,196 stone inscriptions.

Most runic writings from the Viking period are in Sweden. Many runestones name people who went on Viking journeys. For example, the Kjula runestone tells of wars in Western Europe. The Turinge Runestone speaks of a war band in Eastern Europe. Swedish runestones are mostly from the 1000s and often have detailed messages. The Färentuna, Hillersjö, and Snottsta and Vreta stones give much detail about one family.

Other runestones mention men who died on Viking trips. The England runestones are about 30 stones in Sweden that talk about Viking Age voyages to England. They are one of the largest groups of stones mentioning trips abroad, similar in number to the 30 Greece Runestones and 26 Ingvar Runestones (about a Viking trip to the Middle East). They were carved in Old Norse using the Younger Futhark alphabet.

The Jelling stones date from 960 to 985 AD. The older, smaller stone was put up by King Gorm the Old, Denmark's last pagan king, to honor Queen Thyre. His son, Harald Bluetooth, put up the larger stone to celebrate his conquest of Denmark and Norway and making the Danes Christian. It has three sides: one with an animal, one with Jesus Christ, and one with this message:

King Haraldr ordered these monuments made in memory of Gormr, his father, and in memory of Þyrvé [Thyre], his mother; that Haraldr who won for himself all of Denmark and Norway and made the Danes Christian.

Runic writings are also found outside Scandinavia, in places like Greenland and Istanbul. Runestones show voyages to locations such as Bath, Greece (the Viking name for Byzantine lands), Khwaresm, Jerusalem, Italy, Serkland (the Muslim world), England (including London), and various places in Eastern Europe. Viking Age writings have also been found on the Manx runestones on the Isle of Man. Not all runestones are from the Viking Age, like the Kingittorsuaq Runestone in Greenland, which is from the early 1300s.

Runes in Modern Times

The last known people to use the Runic alphabet were an isolated group called the Elfdalians. They lived in Älvdalen in Sweden. They spoke Elfdalian, a language very close to Old Norse. The people of Älvdalen stopped using runes as late as the 1920s. The last known record of Elfdalian Runes is from 1929. They are a type of Dalecarlian runes, also found in Dalarna.

Elfdalian is now considered a separate language, not just a Swedish dialect, because it's hard for Swedish speakers to understand. Even though schools use Swedish, native Elfdalian speakers are bilingual. Today, there are about 2,000–3,000 native speakers of Elfdalian.

Viking Burial Sites

Many burial sites linked to Vikings are found across Europe and in areas they influenced. These include Scandinavia, the British Isles, Ireland, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Germany, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and Russia. Viking burial customs varied. They included simple graves dug in the ground, large mounds (called tumuli), and sometimes even ship burials.

Old writings suggest that many funerals happened at sea. Funerals involved either burying the body or burning it, depending on local customs. In what is now Sweden, burning bodies was more common. In Denmark, burial was more common, and in Norway, both were used. Viking burial mounds are a key source of information about the Viking Age. The items buried with the dead tell us what was important to them for the afterlife. Some important burial sites include:

- Norway: Oseberg; Gokstad; Borrehaugene.

- Sweden: Gettlinge gravfält; the cemeteries of Birka; Valsgärde; Gamla Uppsala.

- Denmark: Jelling; Lindholm Høje; Ladby ship; Mammen chamber tomb.

- Estonia: Salme ships – the largest and earliest Viking ship burial ground found.

- Scotland: Port an Eilean Mhòir ship burial; Scar boat burial, Orkney.

- Iceland: Mosfellsbær; the boat burial in Vatnsdalur.

- Greenland: Brattahlíð.

- Germany: Hedeby.

- Latvia: Grobiņa.

- Ukraine: the Black Grave.

- Russia: Gnezdovo, Staraya Ladoga.

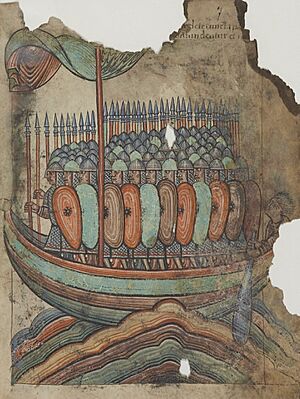

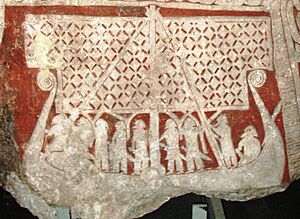

Viking Ships: Masters of the Sea

Archaeologists have found several Viking ships of all sizes. These finds show the amazing skill that went into building them. There were many types of Viking ships, built for different purposes. The most famous type is probably the longship. Longships were made for war and exploration. They were fast and easy to steer, with oars to help when there was no wind. The longship had a long, narrow body and could sail in shallow water, making it easy to land troops. Longships were used a lot by the Leidang, the Scandinavian defense fleets. The longship allowed the Norse to "go Viking," which is why this ship is so linked to the idea of Vikings.

Vikings also built other unique boats, often for peaceful tasks. The knarr was a merchant ship designed to carry a lot of cargo. It had a wider body and needed fewer oars. One Viking invention was the 'beitass', a special spar that helped their ships sail against the wind. Viking ships often carried a smaller boat to move people and goods from the ship to shore.

Ships were a very important part of Viking culture. They helped with daily travel, exploring new lands, raids, conquests, and trade. They also had great religious meaning. Important people were sometimes buried in a ship with animal sacrifices, weapons, and other items. This has been seen at sites like Gokstad and Oseberg in Norway, and Ladby in Denmark. Ship burials were also done by Vikings overseas, as shown by the Salme ships in Estonia.

Well-preserved remains of five Viking ships were found in Roskilde Fjord in the 1960s. These included both longships and knarrs. The ships were sunk there in the 1000s to block a channel and protect Roskilde, then the Danish capital, from sea attacks. The remains of these ships are now on display at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde.

In 2019, archaeologists found two Viking boat graves in Gamla Uppsala. One boat still held the remains of a man, a dog, a horse, and other items. This discovery has taught us more about Viking burial customs in that area.

Viking Society and How People Lived

Viking society had three main groups of people: thralls, karls, and jarls. An old poem called Rígsþula describes this, saying that the god Ríg (also known as Heimdallr) created these three groups. Archaeology has shown that this social structure was real.

- The lowest group was the thralls, who were unfree workers. They made up about a quarter of the population. Their work was very important for Viking society, for daily tasks, big building projects, and trade. Thralls worked on farms and in the homes of karls and jarls. They also built forts, roads, and other large structures. New thralls were either born to thrall parents or were captured by Vikings during their travels in Europe. They were brought back to Scandinavia, used for work, or traded, often for silver or silk.

- Free farmers and craftspeople were called karlar. They owned farms, land, and animals. They did tasks like plowing fields and building houses, but they also used thralls to help them. Other names for karls were bonde or simply free men.

- The highest group was the jarlar, who were wealthy leaders. They owned large estates with big longhouses, horses, and many thralls. The thralls did most of the daily work, while the jarls focused on managing their lands, politics, hunting, and sports. They also visited other jarls or went on expeditions. When a jarl died, valuable items and sometimes people were buried with them, as many archaeological digs have shown.

In daily life, there were many different roles within these groups, and people could sometimes move between them. Titles like hauldr and thegn show that there was some social movement between the karls and jarls.

Other social groups included félag communities, which were like clubs or partnerships. Members of a félag (called félagi) had duties to each other. A félag could be for certain trades, for owning a ship together, or for a military group under a leader. Members of military groups were called drenge. There were also official groups in towns and villages for defense, religion, laws, and the Things (assemblies where laws were made and disputes settled).

The Role of Women in Viking Society

Like in other parts of medieval Europe, most women in Viking society were under the authority of their husbands and fathers. They had little direct political power. However, old writings show that free Viking women had more independence and rights than women in many other places. This is seen in Icelandic and Norwegian laws.

Most free Viking women were homemakers. A woman's standing in society was linked to her husband's. Marriage gave a woman financial security and a social position, known by the title húsfreyja (lady of the house). Norse laws gave the housewife authority over the 'indoor household'. She had important roles in managing the farm's resources, doing business, and raising children, though she shared some of this with her husband.

After age 20, an unmarried woman, called maer or mey, became legally independent. She could decide where to live and was seen as her own person by law. However, marriages were usually arranged by families, so she didn't always choose her husband. The groom would pay a bride-price (mundr) to the bride's family, and the bride brought assets into the marriage as a dowry. A married woman could divorce her husband and remarry.

Some women lived with men and had children without formal marriage; such a woman was called a frilla. She was usually the partner of a wealthy man who also had a wife. The wife had authority over these partners if they lived in her home. Through her relationship with a higher-status man, a partner and her family could gain social standing, though her position was less secure than a wife's. There was little difference between children born inside or outside marriage: both could inherit property from their parents. However, children born in marriage had more inheritance rights.

A woman had the right to inherit part of her husband's property if he died. Widows had the same independent status as unmarried women. A paternal aunt, niece, and granddaughter, called odalkvinna, all had the right to inherit property from a deceased man. A woman without a husband, sons, or male relatives could inherit not only property but also the position as head of the family when her father or brother died. Such a woman was called Baugrygr, and she had all the rights of a family leader until she married, when her rights transferred to her new husband.

Women also had religious authority. They served as priestesses (gydja) and oracles (sejdkvinna). They were active in art as poets (skalder) and rune masters, and as merchants and medicine women. There might have been female business owners who worked in textile production. Women may also have held military roles: stories about shieldmaidens are not fully confirmed, but some archaeological finds, like the Birka female Viking warrior, suggest that some women held military authority.

These freedoms for Viking women slowly disappeared after Christianity arrived. After the late 1200s, these rights are no longer mentioned.

Studies of Viking Age burials suggest that women lived longer, with most living past age 35. Before the Viking Age, many women died between 20 and 35, likely due to childbirth problems.

Studying skeletal remains also helps us understand the health and nutrition of boys and girls in the past. Burials from Scandinavia and other European countries suggest that, compared to other societies, girls in rural Scandinavia had remarkably good health and nutrition. This meant they grew stronger and healthier.

How Vikings Looked

Scandinavian Vikings looked similar to modern Scandinavians. Their skin was fair, and their hair color varied between blond, dark, and reddish. Genetic studies suggest that blond hair was common in eastern Sweden, while red hair was more common in western Scandinavia. Most Viking men had shoulder-length hair and beards. Unfree workers (thralls) were usually the only men with short hair. Hair length depended on personal choice and job. For example, men in warfare might have had shorter hair for practical reasons. Men in some areas bleached their hair a golden color. Women also had long hair. Girls often wore it loose or braided, and married women often wore it in a bun. The average height for men was about 1.70 meters (5 feet 7 inches), and for women, about 1.55 meters (5 feet 1 inch).

The three social classes were easy to tell apart by their appearance. Men and women of the Jarls were well-groomed with neat hairstyles. They showed their wealth by wearing expensive clothes (often silk) and finely made jewelry like brooches, belt buckles, necklaces, and arm rings. Almost all jewelry had unique Norse designs (see Viking art). Finger rings were rare, and earrings were not used at all, as they were seen as a Slavic style. Most karls had similar tastes and hygiene, but in a simpler and less expensive way.

Archaeological finds from Scandinavia and Viking settlements in the British Isles support the idea that Vikings were well-groomed and clean. Burying items with the dead was common in Scandinavia throughout the Viking Age. In these burial sites and homes, combs, often made from antler, are commonly found. Hundreds of combs from the 900s have been found at the Viking settlement in Dublin, showing that grooming was a common practice. Similar combs have been found in Viking settlements in Ireland, England, and Scotland. These combs often have linear, interlacing, and geometric patterns, similar to Viking Age art. It seems that people from all levels of Viking society groomed their hair, as combs have been found in both common and aristocratic graves.

Viking Food and Farming

Old stories (sagas) tell us about the Viking diet. But direct evidence, like old garbage dumps, has been very important. Undigested plant remains from old pits in York have given us much information. Recent studies by archaeologists and plant experts have taught us a lot about Viking farming and cooking.

Information from different sources shows a varied cuisine. They prepared and ate all kinds of meat products, like cured, smoked, and whey-preserved meats, sausages, and fresh boiled or fried cuts. There was plenty of seafood, bread, porridges, dairy products, vegetables, fruits, berries, and nuts. Alcoholic drinks like beer, mead, strong fruit wine, and, for the rich, imported wine, were served.

Some livestock were special to the Vikings, including the Icelandic horse, Icelandic cattle, many sheep breeds, the Danish hen, and the Danish goose. Vikings in York mostly ate beef, mutton, and pork, with small amounts of horse meat. Many beef and horse leg bones were split lengthwise to get the marrow. Mutton and pork were cut into leg and shoulder joints. Pig skull and foot bones found in houses show that brawn and trotters were also popular. Hens were kept for meat and eggs. Bones of game birds like black grouse, golden plover, wild ducks, and geese have also been found.

Seafood was important, sometimes even more than meat. Whales and walrus were hunted for food in Norway and the North Atlantic. Seals were hunted almost everywhere. Oysters, mussels, and shrimp were eaten in large amounts. Cod and salmon were popular fish. In southern regions, herring was also important.

Milk and buttermilk were popular for cooking and drinking, but not always available. Milk came from cows, goats, and sheep. Fermented milk products like skyr or surmjölk were made, as well as butter and cheese.

Food was often salted and flavored with spices. Some spices, like black pepper, were imported. Others were grown in herb gardens or gathered in the wild. Homegrown spices included caraway, mustard, and horseradish, found at the Oseberg ship burial. Dill, coriander, and wild celery were found in pits in York. Thyme, juniper berry, sweet gale, yarrow, rue, and peppercress were also used.

Vikings gathered and ate fruits, berries, and nuts. Apples (wild crab apples), plums, and cherries were part of their diet. So were rose hips, raspberry, wild strawberry, blackberry, elderberry, rowan, hawthorn, and various wild berries. Hazelnuts were an important food. Large amounts of walnut shells have been found in cities like Hedeby. The shells were used for dyeing, and it's believed the nuts were eaten.

The invention of the mouldboard plough changed farming in Scandinavia in the early Viking Age. It made it possible to farm even poor soils. In Ribe, grains of rye, barley, oat, and wheat from the 700s have been found. They are believed to have been grown locally. Grains and flour were used for porridges, some cooked with milk, some with fruit and honey. They also made various kinds of bread. Remains of bread from Birka in Sweden were made of barley and wheat. It's unclear if the Norse used yeast for their breads, but their ovens suggest they did. Flax was a very important crop. It was used for oil, food, and most importantly, making linen. More than 40% of all known Viking Age textiles were linen. This suggests it was used much more, as linen doesn't preserve as well as wool.

The quality of food for common people was not always high. Research in York shows that Vikings made bread from wholemeal flour, likely wheat and rye. But it included seeds of cornfield weeds. Corncockle (Agrostemma) would have made the bread dark, but its seeds are poisonous and could make people sick. Seeds of carrots, parsnip, and brassicas were also found, but they were poor quality. The rotary querns used in the Viking Age left tiny stone fragments in the flour. These fragments wore down teeth, which can be seen on skeletal remains from that time.

Viking Sports and Games

Sports were widely practiced and encouraged by the Vikings. Sports that involved weapon training and developing combat skills were popular. These included spear and stone throwing, and testing physical strength through wrestling (like glima), fist fighting, and stone lifting. In mountainous areas, mountain climbing was a sport. Running and jumping tested agility and balance. There's a mention of a sport where people jumped from oar to oar on the outside of a rowing ship. Swimming was popular. Snorri Sturluson describes three types: diving, long-distance swimming, and a contest where two swimmers tried to dunk each other. Children often took part in some sports, and women were also mentioned as swimmers, though it's unclear if they competed. King Olaf Tryggvason was known for his skill in mountain climbing and oar-jumping. He was also good at knife juggling. Skiing and ice skating were the main winter sports and helped adults travel on snow and ice.

Horse fighting was a sport, though the rules are not clear. It seems to have involved two male horses fighting near fenced-off female horses. These fights often ended with one horse dying.

Icelandic writings often mention knattleik, a ball game similar to hockey. It was played with a bat and a small hard ball, usually on ice. It was popular with adults and children and often led to injuries. Knattleik seems to have been played only in Iceland, where it attracted many viewers, as did horse fighting.

Hunting was a sport only in Denmark, where it was not a main food source. Deer and hares were hunted for meat, along with partridges and sea birds. Foxes were hunted to protect farm animals and for their furs. Spears, bows, and later crossbows, were used. Stalking was common, but game was also chased with dogs. Many kinds of traps were also used.

Viking Games and Entertainment

Archaeological finds and old writings show that Vikings had social gatherings and celebrations. Board games and dice games were popular. Game boards were made of carved wood, and pieces were made from wood, bone, or stone. Pieces were also made of glass, amber, and antler, and from foreign materials like walrus tusk and ivory. Vikings played several types of tafl games, including hnefatafl, nitavl (nine men's morris), and kvatrutafl.

Hnefatafl was likely the oldest board game played in medieval Scandinavia. Archaeology shows it was popular early on, and Vikings brought it to England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. The Ockelbo Runestone shows two men possibly playing hnefatafl. One saga suggests that dice games involved gambling.

Beer and mead were served at parties. Music was played, poetry was recited, and stories were told. Music was seen as an art form, and musical skill was valued. Vikings played instruments like harps, lutes, lyres, and fiddles.

How Viking Culture Blended with Others

Viking identity and customs were kept in their settlements, but they also blended with local societies. For example, in Normandy, Vikings quickly adopted Frankish culture. Links to a Viking identity lasted longer in remote islands like Iceland and the Faroes.

Viking Weapons and Warfare

What we know about Viking weapons and armor comes from archaeological finds, pictures, and old Norse stories and laws from the 1200s. By custom, all free Norse men had to own weapons and could carry them always. These weapons showed a Viking's social standing. A wealthy Viking had a full set: a helmet, shield, mail shirt, and sword. However, swords were probably not strong enough for all combat and were often used as symbols or decorations.

A typical bóndi (freeman) was more likely to fight with a spear and shield. Most also carried a seax as a utility knife and side-arm. Bows were used at the start of land battles and at sea. Vikings were unusual for their time in using axes as a main battle weapon. The Húscarls, the elite guards of King Cnut, used two-handed axes that could split shields or metal helmets easily.

The warfare and actions of the Vikings were often shaped by their beliefs in Norse religion, especially their gods Thor and Odin, who were gods of war.

Violence was common in Viking Age Norway. A study of human remains from that time found that 72% of men and 42% of women had injuries from weapons. Violence was less common in Viking Age Denmark, where society was more organized than the clan-based Norwegian society.

Viking Trade and Economy

Vikings created and used large trading networks across the known world. They had a big impact on the economies of Europe and Scandinavia.

Outside of trading centers like Ribe and Hedeby in Denmark, Scandinavia did not use coins much. So, their economy was based on bullion, meaning the purity and weight of precious metals. Silver was most common, but gold was also used. Traders carried small scales to measure weight precisely. This allowed for fair trade even without regular coins.

Goods Traded by Vikings

Organized trade included everything from everyday items to rare luxury products. Viking ship designs, like the knarr, helped them succeed as merchants. Goods imported from other cultures included:

- Spices were bought from Chinese and Persian traders who met Vikings in Russia. Vikings used local spices like caraway and mustard, but imported cinnamon.

- Glass was highly valued. Imported glass was often made into thousands of decorative beads. Åhus in Sweden and Ribe in Denmark were major centers for making glass beads.

- Silk was a very important item from Byzantium (modern Istanbul) and China. Many European cultures valued it, and Vikings used it to show wealth and high status. Many archaeological finds in Scandinavia include silk.

- Wine was imported from France and Germany for the wealthy, adding to their usual mead and beer.

To balance these valuable imports, Vikings exported many goods. These included:

- Amber—fossilized tree resin—was often found on the North Sea and Baltic coasts. It was shaped into beads and ornaments, then traded.

- Fur was also exported for warmth. This included furs from pine martens, foxes, bears, otters, and beavers.

- Cloth and wool. Vikings were skilled at spinning and weaving and exported high-quality woollen cloth.

- Down was collected and exported. The Norwegian west coast supplied eiderdowns, and sometimes feathers were bought from the Samis. Down was used for bedding and warm clothing. Collecting down from steep cliffs was dangerous.

- People who were captured and traded. The Muslim writer Ahmad ibn Rustah described how the Viking Rus' lived by "pillaging alone." They were very active in capturing people. Most of these people were taken to Scandinavia, but others were sold in markets in Atil to meet demand in cities in Asia and North Africa. The increase in this trade in the 800s is seen in the number of coins from Central Asia found in Scandinavia.

Many of these goods were also traded within the Viking world itself, as well as goods such as soapstone and whetstone. Soapstone was traded with the Norse on Iceland and in Jutland, who used it for pottery. Whetstones were traded and used for sharpening weapons, tools and knives. There are indications from Ribe and surrounding areas, that the extensive medieval trade with oxen and cattle from Jutland (see Ox Road), reach as far back as c. 720 AD. This trade satisfied the Vikings' need for leather and meat to some extent, and perhaps hides for parchment production on the European mainland. Wool was also very important as a domestic product for the Vikings, to produce warm clothing for the cold Scandinavian and Nordic climate, and for sails. Sails for Viking ships required large amounts of wool, as evidenced by experimental archaeology. There are archaeological signs of organised textile productions in Scandinavia, reaching as far back as the early Iron Ages. Artisans and craftsmen in the larger towns were supplied with antlers from organised hunting with large-scale reindeer traps in the far north. They were used as raw material for making everyday utensils like combs.

The Viking Legacy

Viking Influence on the English Language

The Vikings greatly influenced Old English, which helped shape Modern English. Nouns in English lost their grammatical gender, and verb endings became simpler. The way we can end a sentence with a preposition (like "who are you talking to?") also came from Old Norse.

How People Saw Vikings in the Middle Ages

In England, the Viking Age began dramatically on June 8, 793 AD. Norsemen destroyed the abbey on the island of Lindisfarne. This attack shocked Europe's royal courts and made them aware of the Vikings. "Never before has such an atrocity been seen," said the scholar Alcuin of York. Medieval Christians in Europe were not ready for the Viking attacks. They could only explain the suffering as the "Wrath of God." More than any other event, the Lindisfarne attack made Vikings seem like demons for the next twelve centuries. It wasn't until the 1890s that scholars outside Scandinavia began to truly appreciate Viking achievements, like their art, technology, and sailing skills.

Norse Mythology, sagas, and literature tell us about Scandinavian culture and religion through stories of heroes and myths. This information was first passed down orally. Later, Christian scholars, like the Icelanders Snorri Sturluson, wrote it down. Many sagas were written in Iceland and preserved there because Icelanders remained interested in Norse literature and laws.

The 200-year Viking influence on European history is full of stories of raids and settlements. Most of these stories come from Western European witnesses. Less common, but still important, are mentions of Vikings in Eastern writings. These include the Nestor chronicles and the Novgorod chronicles. There are also brief mentions by Photius, a leader in Constantinople, about the first Viking attack on the Byzantine Empire. Other writers who told Viking history include Adam of Bremen. He wrote that in Zealand, there was "much gold... accumulated by piracy. These pirates, which are called wichingi by their own people... pay tribute to the Danish king." In 991 AD, the Battle of Maldon between Viking raiders and the people of Maldon was remembered in a famous poem.

Later Ideas About Vikings

Early books about what we now call Viking culture appeared in the 1500s. These included Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (History of the northern people) by Olaus Magnus (1555). The first edition of the 13th-century Gesta Danorum (Deeds of the Danes) by Saxo Grammaticus came out in 1514. More books were published in the 1600s, including Latin translations of the Edda.

In Scandinavia, scholars in the 1600s and 1700s used runic writings and Icelandic sagas as historical sources. An important early British scholar was George Hickes, who published his Dictionary of the Old Northern Languages in 1703–05. During the 1700s, British interest in Iceland and early Scandinavian culture grew. This was shown in English translations of Old Norse texts and poems praising Viking virtues.

The word "viking" became popular in the early 1800s because of Erik Gustaf Geijer's poem, The Viking. Geijer's poem helped spread a new, romantic idea of the Viking, which was not always historically accurate. The renewed interest in the Old North during the Romanticism period had political meanings at the time. The Geatish Society, which Geijer belonged to, helped spread this idea. Another Swedish author, Esaias Tegnér, also a member of the Geatish Society, wrote a modern version of Friðþjófs saga hins frœkna, which became very popular in Nordic countries, the UK, and Germany.

Fascination with Vikings reached its peak during the Viking revival in the late 1700s and 1800s. This was part of a movement called Romantic nationalism. In Britain, it was called Septentrionalism. In Germany, it was linked to Richard Wagner's music. In Scandinavia, it was called Scandinavism. New scholarly books about the Viking Age began to reach readers in Britain. Archaeologists started digging up Britain's Viking past. Language experts began to find Viking-Age origins for local words. New dictionaries of Old Norse helped Victorians understand the Icelandic sagas.

Until recently, Viking Age history was mostly based on Icelandic sagas and other old writings. Now, historians rely more on archaeology and numismatics (the study of coins). These fields have greatly helped us understand the period.

Experimental Archaeology: Bringing Vikings to Life

Experimental archaeology of the Viking Age is a growing field. Several places are dedicated to this, such as Jorvik Viking Centre in the UK, Sagnlandet Lejre and Ribe Viking Center in Denmark, Foteviken Museum in Sweden, and Lofotr Viking Museum in Norway. People who reenact Viking life have tried activities like iron smelting and forging using Norse techniques. For example, at Norstead in Newfoundland.

On July 1, 2007, a reconstructed Viking ship called Sea Stallion began a journey from Roskilde, Denmark, to Dublin, Ireland. The remains of this ship and four others were found in 1962. Tree-ring analysis showed the ship was built of oak near Dublin around 1042. Seventy crew members from many countries sailed the ship back to its home. Sea Stallion arrived in Dublin on August 14, 2007. The trip's goal was to test the ship's seaworthiness, speed, and how well it could be steered in rough seas. The crew learned how the long, narrow, flexible hull handled tough ocean waves. The expedition also gave valuable new information about Viking longships and society. The ship was built using Viking tools, materials, and many of the same methods as the original.

Other Viking ship replicas, often of the Gokstad ship or Skuldelev types, have also been built and tested. The Snorri (a knarr replica) sailed from Greenland to Newfoundland in 1998.

Common Misconceptions About Vikings

Did Vikings Wear Horned Helmets?

Except for a few images of ritual helmets (which might have stylized ravens, snakes, or horns), no pictures of Viking warrior helmets, and no preserved helmets, have horns. The close-quarters fighting style of Vikings would have made horned helmets clumsy and dangerous to their own side.

Historians believe that Viking warriors did not wear horned helmets. Whether such helmets were used for other, ritual purposes in Scandinavian culture is not proven. The common idea that Viking warriors wore horned helmets was partly spread by enthusiasts in the 1800s. These groups promoted Norse mythology in art and for other cultural goals.

Vikings were often shown with winged helmets and clothing from Classical antiquity. This was done to make Vikings and their myths seem more important by linking them to the Classical world, which was highly admired in Europe.

The later myth created by national romantic ideas mixed the Viking Age with parts of the Nordic Bronze Age, which was about 2,000 years earlier. Horned helmets from the Bronze Age were shown in petroglyphs (rock carvings) and found in archaeological digs. They were probably used for ceremonies.

Cartoons like Hägar the Horrible and Vicky the Viking, and sports teams like the Minnesota Vikings and Canberra Raiders, have kept the myth of the horned helmet alive.

Real Viking helmets were conical, made from hard leather with wood and metal for regular soldiers. Iron helmets with masks and mail were for chieftains, based on earlier helmets from central Sweden. The only original Viking helmet found is the Gjermundbu helmet in Norway. This iron helmet is from the 900s.

Were Vikings Always Barbaric?

The image of wild-haired, dirty savages sometimes linked to Vikings in popular culture is not accurate. Viking actions were often misreported. Writings by people like Adam of Bremen told stories of Viking savagery and uncleanliness that are largely debated today.

Did Vikings Drink from Skulls?

There is no evidence that Vikings drank from the skulls of defeated enemies. This idea came from a misunderstanding of a poem that spoke of heroes drinking from ór bjúgviðum hausa (branches of skulls). This was a reference to drinking horns, but it was mistranslated in the 1600s to mean the skulls of the dead.

Viking Genetic Legacy

A 2020 study looked at the DNA of 442 people from Viking Age sites across Europe. They found that these people were closely related to modern Scandinavians. The male DNA (Y-DNA) was also similar to modern Scandinavians. The most common Y-DNA types were I1, R1b, and R1a (especially the Scandinavian R1a-Z284 type). The study showed that it was common for Norse settlers to marry women from other lands. Some people in the study, like those found in Foggia, Italy, had typical Scandinavian Y-DNA but also southern European ancestry. This suggests they were descendants of Viking men and local women. These individuals from Foggia were likely Normans. The same pattern of Scandinavian male DNA and local ancestry was seen in other samples, like Varangians near lake Ladoga and Vikings in England. This suggests Viking men married into local families in those places too.

The study found evidence of Swedish people moving into Estonia and Finland. It also found Norwegian people moving into Ireland, Iceland, and Greenland during the Viking Age. However, the study noted that Viking Age Danish ancestry in the British Isles cannot be easily told apart from that of the Angles and Saxons, who migrated from Jutland and northern Germany in the 400s and 500s AD.

The 2020 study also looked at the remains of 42 people from the Salme ship burials in Estonia. These were warriors killed in battle and buried with valuable weapons and armor. DNA and isotope analysis showed that these men came from central Sweden.

Studies of female ancestry show Norse descent in areas closest to Scandinavia, like the Shetland and Orkney islands. Inhabitants of lands farther away show most Norse descent in the male Y-chromosome lines.

A special genetic study in Liverpool showed strong Norse heritage. Up to 50% of males in families living there before the industrial age had Norse ancestry. High percentages of Norse ancestry were also found among males in the Wirral and West Lancashire. This was similar to the percentage found in the Orkney Islands.

Recent research suggests that the Celtic warrior Somerled, who drove the Vikings out of western Scotland, might have had Viking descent.

The 2020 study also examined an elite warrior burial from Bodzia (Poland) from 1010–1020 AD. This cemetery has strong links to Scandinavia and Kievan Rus. The Bodzia man was not a simple warrior but likely belonged to a princely family. His burial was the richest in the cemetery. Analysis of his teeth showed he was not from the local area. It is thought he came to Poland with the Prince of Kiev, Sviatopolk the Accursed, and died violently in battle. This matches events from 1018 AD when Sviatopolk disappeared after retreating to Poland. It's even possible the Bodzia man was Sviatopolk himself, as records of the Rurikid family from this time are not very detailed. The Bodzia man had Scandinavian ancestry and some Russian mix.

Related Pages

See also

In Spanish: Vikingo para niños

In Spanish: Vikingo para niños

- Faroese people

- Geats

- Gotlander

- Gutasaga

- Oeselians

- Proto-Norse language

- Swedes (Germanic tribe)

- Ushkuiniks, Novgorod's privateers

- Viking raid warfare and tactics

- Wokou

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |