Pinniped facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pinnipeds |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Clockwise from top left: New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri), southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus), walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) and grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Subclades | |

|

|

|

|

| Range map |

Pinnipeds are a group of amazing sea mammals. They are often called seals and their relatives. These animals spend most of their lives in the water. They are part of a larger group of meat-eating animals called Carnivora.

There are three main types of pinnipeds:

- Walruses (Family Odobenidae)

- Eared seals (Family Otariidae), which include sea lions and fur seals

- True seals (Family Phocidae)

Pinnipeds have sleek, barrel-shaped bodies. Their bodies are perfect for living in the water. They have flippers instead of hands and feet. They also have big bodies, faces that look a bit like dogs, and large eyes. Unlike cetaceans (like whales and dolphins), pinnipeds have noses on their faces. Their nostrils close tightly when they go underwater.

Just like whales, pinnipeds have a thick layer of blubber (fat) under their skin. This blubber helps them stay warm in cold water. It also acts as a food reserve. When they can't find food, they use the fat in their blubber for energy. Pinnipeds are carnivorous, meaning they only eat meat. They mostly eat fish and squid. Sadly, many pinnipeds can become food for sharks or orca whales.

You might see seals trained in zoos or aquariums. They can do fun shows! But did you know that in Sweden, it's against the law to train a seal to balance a ball on its nose?

Contents

How Pinnipeds Sleep

Pinnipeds can sleep both in the water and on land. Both places have dangers for them. In the northern parts of the world, polar bears can be a threat on land. In the water, sharks are a danger.

When sleeping in water, these animals go through different sleep stages. They still do important things while sleeping. They come to the surface to breathe now and then. They also open an eye for a short time. Different types of pinnipeds might do this slightly differently. Other sea mammals, like dolphins, have similar ways of sleeping.

Body and How it Works

Pinnipeds have smooth bodies. They have very small or no outside ear flaps. Their tails are small, and their arms and legs have changed into flippers. Pinnipeds come in many sizes. The smallest is the Baikal seal, about 1 meter (3 feet) long and weighing 45 kg (100 pounds). The largest is the southern elephant seal, which can be 5 meters (16 feet) long and weigh 3200 kg (7,000 pounds). Generally, pinnipeds are bigger than other meat-eating animals.

Some species have males that are much larger than females. This is called sexual dimorphism. It often happens in species where one male mates with many females. For example, male elephant seals are much bigger than females. In other species, males and females are closer in size.

Most pinnipeds have fur coats. The walrus is an exception, with only a few hairs. Even some furry pinnipeds, like sea lions, have less hair than most land mammals. Young pups of species that live on ice have very thick coats called lanugo. This thick fur traps heat from the sun and keeps the pups warm.

Pinnipeds usually have countershaded fur. This means they are darker on their backs and lighter on their bellies. This helps them blend in with the ocean water. The pure white fur of harp seal pups helps them hide in their snowy Arctic home. Some species, like ribbon seals, have cool patterns of light and dark colors. All pinnipeds molt, meaning they shed their fur. True seals molt once a year, while eared seals shed fur gradually all year long.

Pinnipeds have a thick layer of fat under their skin called blubber. This blubber is especially thick in true seals and walruses. Blubber keeps them warm and gives them energy when they can't eat. Blubber can make up to half of a pinniped's body weight! Walruses and elephant seals can have blubber layers several inches thick. Pups are born with a thin layer of blubber. Some species make up for this with their thick lanugo fur.

How Pinnipeds Move

Unlike other sea mammals, pinnipeds have two pairs of flippers: front flippers and back flippers. Their elbows and ankles are hidden inside their bodies. Pinnipeds usually swim slower than whales and dolphins. They typically cruise at 5–15 knots (9–28 km/h). Whales and dolphins can swim around 20 knots (37 km/h). However, pinnipeds are more agile and flexible.

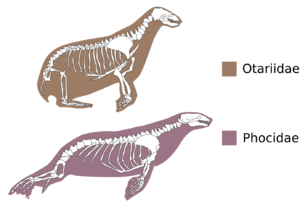

Eared seals, like the California sea lion, use their front flippers to swim. They move their flippers like penguins or sea turtles. Their swimming is not continuous; they glide between each stroke. The hind-flippers of eared seals help them stay stable. True seals and walruses swim by moving their hind-flippers and lower body from side to side. Their front flippers are mainly used for steering.

Some sea lions and harbor seals occasionally leap out of the water. This might help them travel faster. Sea lions are also known to "ride" waves, which probably saves them energy.

Pinnipeds can also move on land, though not as easily as land animals. Eared seals and walruses can turn their hind-flippers forward. This allows them to "walk" on all fours. They use their heads and necks to create momentum as they move. Sea lions have even been seen climbing stairs!

True seals are less agile on land. They cannot pull their hind-flippers forward. They move by lunging, bouncing, and wiggling. Their front flippers help them stay balanced. Moving on land is easier for true seals on ice, as they can slide along.

How Pinnipeds Sense the World

Pinnipeds have large eyes for their body size. Their eyes are usually at the front of their heads. The walrus is different, with smaller eyes on the sides of its head. This is because walruses eat slow-moving creatures on the seafloor and don't need sharp vision.

A pinniped's eye is made for seeing both underwater and in the air. They have a special eye structure that helps them see clearly in both environments. Pinnipeds also have strong eye muscles. This allows them to change the size of their pupil a lot. When the pupil is small, it's often pear-shaped.

On land, pinnipeds are a bit near-sighted in dim light. But they have a special layer in their eyes called a tapetum lucidum. This layer reflects light back through the retina, helping them see better in the dark. Ice-living seals, like the harp seal, have eyes that can handle a lot of UV radiation from bright, snowy places. This means they don't get snow blindness. Pinnipeds likely have limited color vision. They also produce a lot of mucus to protect their eyes.

Pinnipeds hear very well underwater. They can hear sounds up to 70,000 Hz. Their hearing in the air is not as good as many land mammals. Even though they can hear many of the same sounds as humans, their hearing is not as sensitive in the air.

Pinnipeds have a good sense of smell on land. But it's useless underwater because their nostrils are closed.

Pinnipeds have a very good sense of touch. Their whiskers (called vibrissae) have ten times more nerves than land mammals' whiskers. This helps them feel vibrations in the water very well. This is useful when they are looking for food, especially in the dark. Walruses have the most whiskers, about 600–700! These are very important for finding prey on the muddy seafloor. Pinnipeds don't move their whiskers around like some land animals. Instead, they extend them and keep them still to examine things. Whiskers also help them navigate. Spotted seals seem to use them to find holes in the ice.

Where Pinnipeds Live

Today, most pinnipeds live in cold places. You can find them in the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and the Southern Ocean. However, Monk seals and some eared seals live in warmer, tropical waters. Pinnipeds usually need cool water that is full of nutrients. The water temperature is usually below 20°C (68°F). Even those in warm climates live in areas with cold, nutrient-rich water because of ocean currents. Only the monk seals live in waters that are not typically cool.

Two species, the Caspian seal and Baikal seal, live in large lakes that are not connected to the ocean. The Baikal seal is the only pinniped that lives only in freshwater. However, some ringed seals live in landlocked lakes in Russia. Harbor seals are also known to visit rivers and lakes and sometimes stay for up to a year. Other species that enter freshwater include California and South American sea lions.

Pinnipeds also use many different places on land to rest. In warm areas, they rest on sandy beaches, rocky shores, mud flats, sea caves, and tidepools. Some even use human-made structures like piers and oil platforms. Pinnipeds might move further inland to rest in sand dunes or climb steep cliffs. Species that live in polar regions use either stable ice (fast ice) or floating ice (pack ice).

Life Cycle

Reproduction

Male pinnipeds have different ways of finding mates. Males of some species, like elephant seals and northern fur seals, fight to protect groups of females. These groups are called harems. In other species, like most sea lions, males defend areas on the breeding grounds. Females can move freely between these areas. Fighting for females or territories is a common part of how male pinnipeds breed.

Eared seals, which spend more time on land, gather in large groups on beaches or rocks during the summer. Because of this, their breeding behavior is easier to watch and has been studied a lot. Less is known about the breeding behavior of walruses and many true seals.

After giving birth, mother seals feed their young for a certain amount of time. This is called suckling.

After a mother seal goes on her first hunting trip, her most important job is to find her own pup among many others. Feeding another mother's pup would waste a lot of her energy. Mother seals solve this by recognizing voices. The mother and pup learn each other's voices in the first few days after the pup is born. When the mother returns, she calls out to her pup, and the pup calls back. This helps the mother find her own pup and ensures she doesn't waste energy on the wrong one.

Diving Abilities

Some pinnipeds can hold their breath for almost two hours underwater! They do this by saving oxygen. During long dives, their heart rate can slow down to about one-tenth of its normal speed. Blood flow to most parts of the body is reduced. Only important organs like the sense organs and nervous system get normal blood flow. They can also handle more pain and tiredness from lactic acid buildup than other mammals. But once they come back to the surface, they need time to recover and get their body chemistry back to normal.

How Pinnipeds Sleep in Water

Pinnipeds spend many months at sea. So, they have to sleep in the water. Scientists have seen them sleeping for minutes at a time. They slowly drift downwards, often on their backs.

Like other sea mammals, pinnipeds can sleep with half of their brain awake. This helps them stay aware of their surroundings. It allows them to detect and escape from predators. When pinnipeds sleep on land, both sides of their brain can go into sleep mode.

Ecology

What Pinnipeds Eat

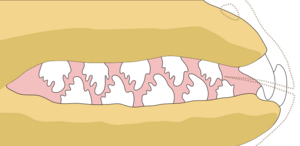

Pinnipeds are meat-eaters. They eat fish, shellfish, squid, penguins, and other sea creatures. Most pinnipeds eat a variety of foods. But some specialize. For example, Ross seals and southern elephant seals mostly eat squid. Crabeater seals mainly eat krill. Ringed seals almost only eat crustaceans. The walrus eats molluscs by sucking the soft parts out of their shells.

Some seals eat warm-blooded prey, including other seals. The leopard seal is probably the most meat-eating pinniped. It eats penguins, as well as crabeater and Ross seals. The South American sea lion also eats penguins, flying seabirds, and young South American fur seals. Steller sea lions eat northern fur seal pups, common seal pups, and birds.

Who Eats Pinnipeds

Almost all pinnipeds can be eaten by orcas and larger sharks. In the Arctic, pinnipeds are an important food source for polar bears. However, seals in the Antarctic are not hunted by land predators.

Pinniped Survival and Threats

As the Arctic ice melts, more pinnipeds are coming onto the shores. Walruses and spotted seals in the United States, Canada, and Russia are showing signs of a mysterious, often deadly disease. Harp seals in Greenland might also be affected.

Sadly, the Caribbean monk seal was declared extinct in 2008.

Images for kids

-

Male and female South American sea lions, showing sexual dimorphism

-

Frontal view of brown fur seal head

-

Walrus on ice off Alaska. This species has a discontinuous distribution around the Arctic Circle.

-

Steller sea lion with white sturgeon

-

Leopard seal capturing emperor penguin

-

Inuit seal sculptures at the Linden Museum

-

Grey seal on beach occupied by humans near Niechorze, Poland. Pinnipeds and humans may compete for space and resources.

See also

In Spanish: Pinnipedia para niños

In Spanish: Pinnipedia para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |