Caribbean monk seal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Caribbean monk seal |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Specimen in the New York Aquarium, c. 1910 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Genus: | Neomonachus |

| Species: |

†N. tropicalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Neomonachus tropicalis (Gray, 1850)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Monachus tropicalis (Gray, 1850) |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Caribbean monk seal (Neomonachus tropicalis) was a type of seal. It was also called the West Indian seal or sea wolf. These seals lived in the waters around Saint Kitts and Nevis. Sadly, they are now believed to be extinct.

The main dangers to Caribbean monk seals were sharks and humans. People hunted these seals a lot for their oil. Also, too much fishing meant there wasn't enough food for the seals. These are the main reasons why they disappeared. The last time anyone officially saw a Caribbean monk seal was in 1952. This sighting happened at Serranilla Bank, which is between Jamaica and Nicaragua. In 2008, the United States officially said the species was extinct. This decision came after a five-year search for the seals. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Marine Fisheries Service did this search. Caribbean monk seals were closely related to Hawaiian monk seals, which live near Hawaiian Islands. Hawaiian monk seals are now endangered. They were also related to Mediterranean monk seals, another endangered species.

Contents

What the Caribbean Monk Seal Looked Like

Caribbean monk seals had a strong, long body. They could grow to be almost 2.4 meters (8 feet) long. They weighed between 170 and 270 kilograms (375 to 600 pounds). Male seals were probably a bit bigger than females. This is similar to Mediterranean monk seals.

Like other monk seals, they had a special head and face. Their head was round with a wide snout. They had large, wide-set eyes and nostrils that opened upwards. Their whisker pads were big, with long, light-colored whiskers. Their front flippers were short with small claws. Their back flippers were thin. Their fur was brownish or grayish. The underside of their body was lighter than their back. Adult seals were darker than younger, paler seals. Caribbean monk seals sometimes had algae growing on their fur. This made them look a bit green, just like Hawaiian monk seals.

How They Lived and Behaved

Historical records show that these seals rested on land in large groups. They would "haul out" onto sandy beaches. A group usually had 20 to 40 seals. Sometimes, there were up to 100 seals together. These groups might have been organized by age. Their food was mostly fish and crustaceans like crabs.

Like other true seals, Caribbean monk seals moved slowly on land. They were not afraid of humans and were quite curious. Hunters took advantage of this calm nature.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Caribbean monk seals had a long season for having their babies. This is common for seals living in warm places. In Mexico, the main breeding time was in early December. Like other monk seals, they had four nipples to feed their young. Newborn pups were about 1 meter (3 feet) long. They weighed about 16 to 18 kilograms (35 to 40 pounds). They were born with sleek, black fur. It is thought that these seals lived for about twenty years.

A tiny creature called the Caribbean monk seal nasal mite lived only inside the seal's nose. When the seals died out, these mites also disappeared.

Where They Lived

Caribbean monk seals lived in the warm waters of the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the western Atlantic Ocean. They likely preferred to rest on quiet, sandy beaches. These beaches were usually on isolated islands or atolls. Sometimes, they would visit mainland coasts or deeper waters. They probably found their food in shallow lagoons and coral reefs.

Their Story with Humans

The first time humans wrote about Caribbean monk seals was in the travel notes of Christopher Columbus. In August 1494, his ship stopped near Alto Velo Island, south of Hispaniola. A group of men went ashore and killed eight seals resting on the beach.

Another early meeting was when Juan Ponce de León found the Dry Tortugas Islands. On June 21, 1513, he sent men to explore. They killed fourteen of the calm seals there. Many more records from the past show seals being found and hunted. This happened in places like Guadeloupe, the Alacrane Islands, the Bahamas, the Pedro Cays, and Cuba.

By 1688, sugar plantation owners were sending out hunting groups. They killed hundreds of seals every night. They needed the seal oil to make their machines work. In 1707, fishermen were also killing hundreds of seals for oil to light their lamps. By 1850, so many seals had been killed that there were not enough left for commercial hunting.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, scientists went to the Caribbean to study the seals. In December 1886, the first scientific trip to research seals happened. It was led by H. A. Ward and Professor F. Ferrari Perez. They went to a group of reefs called the Triangles. Even though they were there for only four days, they killed and took away forty-two seals for study. Two of these seals are still in museums today. They also caught a newborn seal pup, but it died a week later.

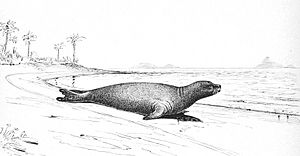

The first Caribbean monk seal to live in a zoo for a long time was a female. She lived at The New York Aquarium. She was caught in 1897 and lived there for five and a half years, dying in 1903. In 1909, the New York Aquarium got four more Caribbean monk seals. Three were young, and one was an adult male.

Why They Disappeared

During the first half of the 1900s, it became very rare to see Caribbean monk seals. In 1908, a small group was seen at the Tortugas Islands, where many seals used to be. In 1915, fishermen caught six seals. These were sent to Florida and later released. In March 1922, a seal was killed near Key West, Florida. There were also sightings on the Texas coast in 1926 and 1932. The last seal known to be killed by humans was on the Pedro Cays in 1939. Two more seals were seen in November 1949 near Kingston, Jamaica. The last confirmed sighting of a Caribbean monk seal was in 1952 at Serranilla Bank.

Two main things caused the Caribbean monk seal to disappear. The biggest reason was the constant hunting of seals in the 1700s and 1800s. People wanted the oil from their blubber (fat). The huge demand for seal products in the Caribbean led hunters to kill hundreds of seals. The seals were calm and didn't run away from humans. This made it very easy for anyone to kill them.

The second reason was that people caught too many fish on the reefs. These fish were the seals' food. With no fish or other sea creatures to eat, the seals that weren't killed by hunters starved. They also couldn't have babies because there wasn't enough food. Sadly, very little was done to try and save the Caribbean monk seal. By the time it was put on the endangered species list in 1967, it was probably already gone.

Sometimes, local fishermen and divers in Haiti and Jamaica say they see Caribbean monk seals. However, two recent scientific trips did not find any signs of them. Some scientists think these sightings might be of hooded seals. Hooded seals have been seen in places like Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Foca monje del Caribe para niños