Medieval Scandinavian law facts for kids

Old Scandinavian Laws, also known as North Germanic Law, was a system of rules and customs used by people in Scandinavia during the Middle Ages. These laws were first remembered by special people called lawspeakers. After the Viking Age, around the 11th century, these laws started to be written down. This was often done by Christian monks after Christianity became popular in Scandinavia.

At first, these laws were used in small areas called lögsögur. There were also special rules for trading towns, known as the Bjarkey laws. Later, laws were made for entire kingdoms in Scandinavia. Each area had a meeting of free men called a þing (pronounced "thing"), which helped govern the land.

The thing was like a court. People would gather there to use the law and listen to witnesses. They would decide if someone was guilty or not. Most punishments involved paying a fine or being declared an outlaw. Fines were the most common way to settle problems. The amount of the fine depended on how serious the offense was. It also changed based on the social standing of the person who committed the crime or the victim. Sometimes, if people disagreed about who was innocent, they would have a trial. These trials had different tests for men and women. If a crime wasn't reported to the courts, it might go unpunished or be settled privately with a payment. Before the Viking Age ended, there wasn't a written law book. But the system of fines, duels, and declaring criminals as outlaws was common across the Scandinavian world.

Contents

How Laws Worked in Iceland

The best information we have about the Viking legal system comes from Iceland. This is because it was very well recorded there. The Eyrbyggja Saga, a famous old story, shows how people settled disagreements at the Althing. The Althing was Iceland's main assembly.

For example, in one part of the saga, a judge and his jury helped solve a big dispute. They decided that one person's wound would cancel out another's. They also agreed that certain killings and injuries would balance each other out. Some people received money for their injuries, like the man who lost his leg. In the end, all problems were settled, and everyone agreed to be friends. This agreement was kept as long as the main leaders were alive.

In 1117, the Althing decided that all the laws should be written down. This important task was done at Hafliði Másson's farm during the winter and published the next year. The collection of laws from this time is known as the Gray Goose Laws (in Icelandic, Grágás). These laws covered both civil matters and rules for the Christian church in Iceland.

Norway's Legal System

Just like other Scandinavian countries in the Medieval Age, Norway used a system of þings. These were assemblies where kings and leaders would meet to solve legal problems. Over time, Norway developed four main regional assemblies: Frostating, Gulating, Eidsivating, and Borgarting. There were also smaller þings, like Haugating, which didn't become as important for making laws. A jury at these meetings usually had 12, 24, or 36 members, depending on how important the case was.

One common way to decide a case in early medieval Norway was a holmgang. This was a duel between the person accusing and the person accused. People believed that the winner of the duel was favored by the gods and was therefore innocent. Sometimes, people were also declared outlaws. For example, Bjorn, the son of Ketil Flat-Nose, was declared an outlaw by a thing called by King Harald at the start of the Eyrbyggja Saga.

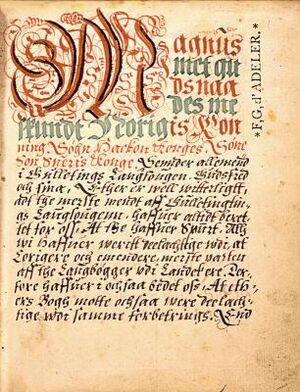

As the king's power grew in Norway from the 11th century onwards, laws were increasingly written down. Kings then issued these laws as royal decrees. For instance, trade in towns was regulated by the Bjarkey laws. The laws of the four main þings were put into written codes during the 13th century. This led to texts like the Frostathing Law. Magnus I of Norway ("the good") played a big part in this. Later, during the rule of Magnus VI of Norway ("the lawmender"), the first national law for all of Norway was created between 1274 and 1276. This is known as Magnus Lagabøtes landslov. It was later joined by more law codes for the country's cities from 1276, called Magnus Lagabøtes bylov.

The Magnus Lagabøtes landslov stayed mostly the same as a key part of Norwegian law until the Norwegian Code was issued by Christian V of Denmark in 1688. However, some parts of today's Law of Norway are still thought to come directly from ancient Norwegian property laws. For example, Udal law is believed to have very old origins.

The Treaty of Perth moved the Outer Hebrides and Isle of Man to be under Scottish law. But Norse law and rule still applied to Shetland and Orkney.

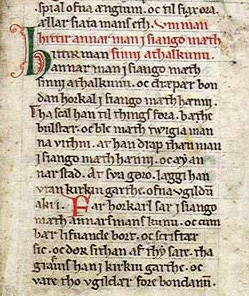

Denmark's Legal System

Medieval Denmark was split into three main areas, each with its own provincial law. The Scanian Law was used in the Scanian lands. The Zealandic Law was for Zealand and Lolland. The Jutlandic Law was used in Jutland (both North and South) and Funen. The Scanian lands were part of Denmark until the mid-17th century. The Scanian Law is even older than similar provincial laws in Sweden. It was written down around 1200 and exists in several old books. The oldest book we still have, SKB B74, was made between 1225 and 1275. It is now kept at the Swedish Royal Library. Another copy, the Codex Runicus, was written entirely using runic letters around 1300. It is now at the Arnamagnæan Institute at the University of Copenhagen. These books are copies of even older laws, making the Scanian Law one of the oldest provincial laws in the Nordic countries.

All three of these provincial laws were given by King Valdemar the Victorious. The newest of the three, the Jutlandic Law, was given in 1241. Zealand later received two more laws: King Eric's Zealandic Law and the Zealandic church law. It's not clear which King Eric the first law refers to.

These three laws were replaced in 1683 by King Christian V's Danish Law. However, this new law was never used in Schleswig. So, the Jutlandic Law continued to be used in that area. The oldest known copy of the Jutlandic Law, Codex Holmiensis 37, is currently owned by the Swedish Royal Library. Recent studies have shown that this copy was not taken as war treasure by Sweden in the 1657-1660 wars. It seems the book was still owned by Danes in the early 18th century.

Sweden's Legal System

The earliest written law from what is now Sweden seems to be the Forsaringen. This is an iron ring from a church door in Forsa, Hälsingland. It has a runic inscription that was once thought to be from the High Middle Ages, but more recently, it's been dated to the 9th or 10th century. We're not entirely sure what the inscription means, but it seems to list fines, with the fine doubling for each new offense.

The first major Swedish law texts are the provincial laws (in Swedish, landskapslag). These were the main way law was handled in Sweden during the Middle Ages. Written records of the landskaplagar date from after 1280. The provinces of Sweden, or landskap, were almost like separate countries and had their own laws. Provincial laws are known to have existed in Västergötland, Östergötland, Dalarna, Hälsingland, Södermanland, Law of Uppland, Västmanland, Värmland, and Närke. A provincial law called Gutalagen also existed for Gotland. In Finland, local common laws were not written down, but in some parts of Finland, the Hälsingland law was used.

In older times, the laws were remembered by a lawspeaker (lagman). Around 1200, the laws began to be written down. This was probably due to the influence of clerics (church leaders). The oldest Swedish provincial law is the Westrogothic law or Västgötalagen. It was used in the province of Västergötland in western Sweden. Like Gutalagen, its oldest version was written around 1220. Some rules in it likely came from the Viking Age. For example, a rule that "no man may inherit while he sits in Greece" would have been useful during the Viking Age. Many Swedes served in the Varangian Guard in Greece back then. But this rule was less important when the laws were written down, as such service had mostly stopped.

When a fine was paid, one-third went to the wronged person, one-third to the local area (called a hundred), and one-third to the king.

In 1347, the Swedish provincial laws were replaced by Magnus Eriksson's country law. Gutalagen was used until 1595, and the Scanian Law was used until 1683.

Christianity's Impact on Norse Law

Christianity is thought to have first reached the Scandinavian people during the time of Charlemagne. However, it didn't truly become widespread until the 11th or 12th century. At that point, Olaf Tryggvason made it the official religion of Norway. He is also known for spreading Christianity to the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland, among other areas in Scandinavia.

With Christianity came new laws and ideas. One example was the Járnburdr, which was a "test by fire." In this test, a person had to pick an iron out of boiling water and carry it for nine steps. A week later, if their wounds had not become infected, they were declared innocent. Later, Christians also stopped this practice. Christianity also ended slavery in Scandinavia and stopped the gathering of "cults." Perhaps the biggest change Christianity brought to Viking culture was the power it gave to kings. As the Viking Age moved into a time with more powerful kings, it quickly came to an end. Kings like Olaf Tryggvason, Sweyn Forkbeard, and Sweyn's son Cnut the Great were very powerful, and they were Christian.

The yearly þing meetings continued even after Scandinavia became Christian. In Iceland, especially, the thing was not just a court but also an important social gathering.

Images for kids

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |