Magnus Eriksson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Magnus Eriksson |

|

|---|---|

Magnus on the title page of his Swedish national lawcode (issue 1430)

|

|

| King of Sweden | |

| Reign | 8 July 1319 – 15 February 1364 |

| Coronation | 21 July 1336 |

| Predecessor | Birger |

| Successor | Albert |

| King of Norway | |

| Reign | August 1319 – 1355 |

| Predecessor | Haakon V |

| Successor | Haakon VI |

| Born | April or May 1316 Norway |

| Died | 1 December 1374 (aged 58) Bømlafjorden, Norway (shipwreck) |

| Spouse |

Blanche of Namur

(m. 1335; died 1363) |

| Issue | |

| House | Bjälbo |

| Father | Eric, Duke of Södermanland |

| Mother | Ingeborg of Norway |

Magnus Eriksson (born April or May 1316 – died 1 December 1374) was a powerful king in Scandinavia. He was King of Sweden from 1319 to 1364. He was also King of Norway as Magnus VII from 1319 to 1355. On top of that, he ruled Scania (a part of modern-day Sweden) from 1332 to 1360. Some people who didn't like him called him Magnus Smek, which means Magnus the Caresser.

Magnus is one of the longest-reigning monarchs in Swedish history. Only the current king, Carl XVI Gustaf, has ruled longer.

Contents

Becoming King

Magnus was born in Norway in 1316. His father was Eric, Duke of Södermanland, who was the son of King Magnus Ladulås of Sweden. His mother was Ingeborg, daughter of King Haakon V of Norway.

In 1319, when Magnus was just three years old, he was chosen as the king of Sweden. This happened at a special meeting called Mora Thing. The Swedish leaders wanted to stop the previous king, Birger Magnusson (Magnus's uncle), from coming back to power. In the same year, Magnus was also accepted as the hereditary king of Norway. This took place at Haugating in Tønsberg.

Since Magnus was so young, his mother, Ingeborg, helped rule as a regent. A regent is someone who governs a country when the king or queen is too young or unable to rule. However, Ingeborg was removed from this role in 1322–1323. After that, important local leaders ruled the countries until Magnus was old enough.

Coming of Age and Expanding His Kingdom

Magnus was declared old enough to rule on his own in 1331, when he was 15. This caused some problems in Norway. A law from 1302 said that a king should be 20 years old to rule. Because of this, some Norwegian nobles, like Erling Vidkunsson, started a rebellion. But by 1333, the rebels gave up and accepted King Magnus.

In 1332, the King of Denmark, Christopher II, died. He had lost most of his country because he and his brother had borrowed money and used parts of Denmark as a guarantee. King Magnus saw an opportunity. He paid a large amount of silver to get back the eastern Danish areas. This made him the ruler of Scania as well.

On 21 July 1336, Magnus had a special ceremony in Stockholm. He was crowned king of both Norway and Sweden. This upset some Norwegian nobles even more. They wanted a separate coronation just for Norway. This led to another uprising by Norwegian nobles in 1338.

Family Life

In 1335, King Magnus married Blanche. She was the daughter of John I, Marquis of Namur. Their wedding was in October or early November 1335, possibly at Bohus castle. As a wedding gift, Blanche received control over the areas of Tunsberg in Norway and Lödöse in Sweden.

Magnus and Blanche had two sons, Eric and Haakon. They also had at least two daughters who died when they were babies. These daughters were buried at Ås Abbey.

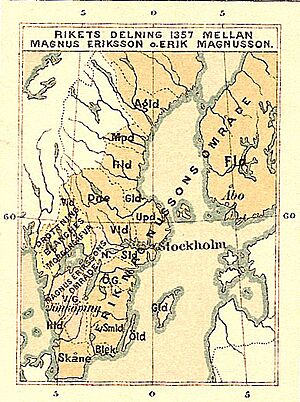

Dividing the Kingdoms

The disagreements with Magnus's rule in Norway led to an agreement in 1343. It was decided that Magnus's younger son, Haakon, would become king of Norway. Magnus would rule as regent until Haakon was old enough. Later that year, it was also announced that Magnus's older son, Eric, would become king of Sweden after Magnus died. This meant that the union between Norway and Sweden would end. Haakon became king of Norway in 1355 when he came of age.

Paying for the new land of Scania meant higher taxes. This made some Swedish nobles unhappy. With support from the Church, they tried to remove Magnus from power. They wanted his older son Eric to be king instead. However, Eric died in 1359, likely from the plague. His wife, Beatrice of Bavaria, and their two sons also died.

Peace with Novgorod

On 12 August 1323, Magnus signed the first treaty between Sweden and Novgorod (a powerful Russian state). This treaty happened at Nöteborg (Orekhov), where Lake Ladoga flows into the Neva River. The treaty set out the areas of influence for the Finns and Karelians. It was meant to be an "eternal peace."

However, Magnus's relationship with the Russian states was not always peaceful. In 1337, there was fighting between Orthodox Karelians and the Swedes. This led to a Swedish attack on the town of Korela and Viborg. During this attack, many merchants from Novgorod and Ladoga were killed. A Swedish commander also captured the fortress at Orekhov. After some talks, a new peace was made in 1339, following the rules of the 1323 treaty. In this new treaty, the Swedes claimed that their commander had acted on his own, without the king's permission.

Ending Slavery

In 1335, King Magnus made an important law. He outlawed thralldom (slavery) for people "born by Christian parents" in Västergötland and Värend. These were the last parts of Sweden where slavery was still allowed. This law officially ended medieval slavery within Sweden's borders. However, it only applied inside Sweden. This loophole was later used for the Swedish slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries.

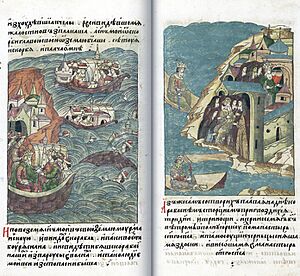

Crusade to Novgorod

Things were quiet between Sweden and Novgorod until 1348. That year, Magnus led a religious war, or crusade, against Novgorod. He marched along the Neva River, forcing tribes there to convert to Christianity. He also briefly captured the fortress of Orekhov for a second time.

However, the people of Novgorod took back the fortress in 1349 after a seven-month siege. Magnus had to retreat, partly because the plague was spreading in the West. He spent much of 1351 trying to get support for more crusades from German cities. But he never returned to attack Novgorod again.

Greenland Connection

In 1355, King Magnus sent a ship (or ships) to Greenland. The goal was to check on the Norse settlements there, especially the Western and Eastern Settlements. The sailors found that the settlements were still Norse and Christian. A special ship, called the Groenlands Knorr, regularly sailed to Greenland until 1369. After it sank, it was not replaced.

Later Years and Death

In 1360, King Valdemar IV of Denmark took back Scania. He then went on to conquer Gotland in 1361. On 27 July 1361, a big battle happened outside Visby, the main city of Gotland. Valdemar won completely. Magnus had warned the people of Visby in a letter and started gathering troops to get Scania back. Valdemar returned to Denmark in August, taking many valuable things with him. Later, in late 1361 or early 1362, the people of Visby rose up against the few Danish soldiers Valdemar had left behind and killed them.

In 1363, some members of the Swedish Council of Aristocracy, led by Bo Jonsson Grip, went to the court of Mecklenburg (a German region). They had been forced to leave Sweden after rebelling against King Magnus. At their request, Albert of Mecklenburg launched an invasion of Sweden. He was supported by several German dukes and counts. Many Hanseatic cities (trading towns) and dukes in Northern Germany also supported Albert. Cities like Stockholm and Kalmar, which had many Hanseatic people, welcomed this change. Albert was declared King of Sweden and crowned on 18 February 1364.

Magnus found safety with his younger son in Norway. According to old Icelandic writings, he drowned in a shipwreck at Lyngholmen in Bømlafjorden on 1 December 1374. He had remained the ruler of Iceland until his death.

How His Reign is Remembered

Even though Magnus added many lands to his rule, his time as king is often seen as a period when the Swedish royal power became weaker. Other countries like Denmark and Mecklenburg interfered in Swedish affairs. Magnus also seemed to struggle with internal opposition from his own nobles. He was sometimes seen as a weak king and criticized for giving too much power to his favorites.

There is a Russian story called the Testament of Magnus. It claims that Magnus did not drown at sea. Instead, it says he realized his mistakes, converted to the Orthodox Christian faith, and became a monk in a monastery in Karelia. However, this story is not true.

See also

In Spanish: Magnus Eriksson para niños

In Spanish: Magnus Eriksson para niños

- Unions of Sweden

- List of abolitionist forerunners