Monarchy of Norway facts for kids

Quick facts for kids King of Norway |

|

|---|---|

| Konge av Norge (Bokmål) Konge av Noreg (Nynorsk) |

|

Royal coat of arms of Norway

|

|

| Incumbent | |

|

|

| Harald V since 17 January 1991 |

|

| Details | |

| Style | His Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Crown Prince Haakon |

| First monarch | Harald Fairhair |

| Formation | c. 872 |

| Residence | Royal Palace in Oslo |

| Website | The Norwegian Monarchy |

Norway is a country with a monarchy, meaning it has a King or Queen as its head of state. This role is passed down through families, making it a hereditary monarchy. Norway is also a constitutional monarchy, which means the King's powers are set by a rulebook called the Constitution. The country also uses a parliamentary system, where the government is chosen by the people's elected representatives.

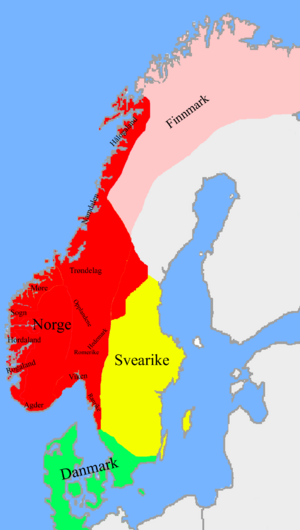

The history of Norway's monarchy goes way back to Harald Fairhair, who united many smaller kingdoms to form Norway. Over time, Norway was also part of unions with Sweden and Denmark.

Today, the King of Norway is Harald V. He became King on January 17, 1991, after his father, Olav V, passed away. The next in line to the throne is his son, Crown Prince Haakon. Both Crown Prince Haakon and the King's wife, Queen Sonja, take part in many public events. The Crown Prince also steps in to act as King when King Harald is away.

The Norwegian royal family is part of the House of Glücksburg, which has roots in Germany. This is the same royal family as the current British and Danish royal families.

Even though the Constitution gives the King important powers, these are usually carried out by the Council of State (the government) in the King's name. Since 1884, Norway has followed a system where the government must have the support of the parliament. This means the King formally appoints the government, but it's based on who the parliament supports.

The King does not usually get involved in daily government decisions. He signs laws, welcomes visitors from other countries, and hosts important state visits. He is also a strong symbol of national unity for Norway. The King is the top leader of the Norwegian Armed Forces and the head of important Norwegian orders like the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav. The King must also be a member of the Church of Norway.

Contents

History of Norway's Kings

The role of King of Norway has existed continuously since Norway was united in 872. While Norway has been a hereditary kingdom for a long time, there have been times when kings were chosen by election. For example, in 1905, the people of Norway voted to confirm Haakon VII as their King. This makes the Norwegian monarchy unique because it has been chosen by the people and regularly gets support from the Storting.

Early Kingdoms

Before the Viking Age, Norway was split into many smaller kingdoms. In these early times, the king was often chosen by important farmers in the area. The king's jobs included being a judge, a priest for special events, and a military leader during wars.

Harald Fairhair is known as the first King of all Norway. He united the country in 872 after winning the Battle of Hafrsfjord. However, it took many years for him to fully control the land. Some historians believe that Olaf II, also known as Saint Olaf, was the first king to truly rule all of Norway from 1015 to 1028. Olaf is also famous for helping Norway become a Christian country. Later, in 1031, he was called Rex Perpetuus Norvegiae ("Eternal King of Norway").

The Middle Ages

During the 12th and 13th centuries, the Norwegian kingdom was at its largest and most powerful. It included Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and parts of the British Isles. The King of Norway had connections with many European kingdoms. Big castles like Haakon's Hall and grand cathedrals, such as Nidaros Cathedral, were built during this time.

In the past, a king had to be chosen by a group of noblemen. While candidates had to be from a royal family, the oldest son was not always automatically chosen. This sometimes led to conflicts and wars, especially during the civil war era. Over time, kings gained more power, and Norway became a hereditary kingdom with clearer rules for who would become king.

After King Haakon VI of Norway died in 1380, his son Olav IV of Norway became King of both Norway and Denmark, and was also chosen as King of Sweden. When Olav died at just 17, his mother, Margrethe, brought the three Scandinavian kingdoms together under one ruler in the Kalmar Union. Olav was the last Norwegian king born in Norway for the next 567 years.

The Black Death in 1349–51 greatly affected Norway, weakening the royal family and noble families. Many farms were left empty, and the income from rents and taxes dropped sharply. This made the Norwegian monarchy weaker in terms of people, noble support, and money.

Union with Denmark

The Kalmar Union was formed not only because of royal family connections but also to stand against the powerful Hanseatic League. In 1523, Sweden left the union for good, leaving Norway in a less equal union with a Danish king.

For the next few centuries, the Norwegian kings mostly lived in Denmark. This made Norway's government weaker because the Norwegian nobles did not have the same trust from the King as the Danish nobles did. The King and his advisors also knew less about Norway's needs because they lived far away.

The church in Norway played a big role in trying to keep Norway's monarchy separate. In the 16th century, a power struggle between Norwegian nobles and the King happened at the same time as the Protestant Reformation. When both struggles failed, the results were harsh. Danish bishops replaced Norwegian Catholic bishops, and the Norwegian church became fully Danish. The Norwegian Council of State was removed in 1536, and more foreigners were given important jobs in Norway.

Danish nobles wanted to make Norway a Danish province to gain more control over choosing future kings. However, because the Norwegian monarchy was hereditary, the King had to keep Norway as a separate kingdom. If the Danish nobles chose someone other than the rightful heir, the union would break apart. This gave the King an advantage in negotiations.

During this time, Danish kings focused more on protecting Danish lands and paid less attention to Norway's interests. As a result, Norway lost territories like Jemtland, Herjedalen, Båhuslen, Shetland, and Orkney to Sweden and Scotland. Also, all contact with Greenland stopped.

In 1661, Frederick III introduced absolute monarchy in Denmark and Norway, giving the King total power. New laws were put in place in both countries. Until then, Norway had used laws from 1274 and 1276. The new laws were basically translations of these older laws into Danish. In 1661, the last parts of local self-government were also removed, though efforts to rebuild them began almost immediately.

Becoming Independent Again

During the Napoleonic Wars, the King of Denmark-Norway sided with France. When Napoleon lost, the King had to give Norway to the King of Sweden in the Treaty of Kiel in 1814. It was first suggested that Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroes would stay with Norway, but this was changed, and they became Danish.

When the Prince of Denmark-Norway, Christian Frederick, who was living in Norway, heard about the treaty, he helped start a movement for Norwegian independence. This movement succeeded partly because of secret support from Denmark, but also because Norwegians strongly wanted to be independent. On April 10, a national assembly met at Eidsvoll to write a constitution. Norway declared independence on May 17, 1814, and chose Christian Frederick as King. A short war with Sweden later that year ended with the Convention of Moss. This led to Christian Frederick stepping down, and the Norwegian Storting chose Charles XIII of Sweden as King of Norway, forming a union between Sweden and Norway. The King then accepted the Norwegian constitution, which was only changed slightly to allow for the union.

This meant the Norwegian monarchy became a constitutional monarchy, where the King's power was limited by the constitution. In this new union, the King was much more a King of Norway than under the Danish system. Only foreign policy was not controlled by Norwegians.

Norway had kept up with new developments from Denmark. However, after the break, Norwegians were able to create a more modern political system than Denmark. Denmark introduced a constitutional monarchy 35 years after Norway. The parliamentary system was introduced in Norway 17 years before Denmark and 33 years before Sweden. The union with Denmark also had some negative effects on the monarchy. For example, Norway lost territory, including large parts of Greenland. Also, very little royal activity happened in Norway, so the country lacks the grand palaces seen in Copenhagen.

Union with Sweden

The Treaty of Kiel said that Norway would be given to the King of Sweden. But Norway rejected this, wanting to decide its own future. A Norwegian assembly was called, and a liberal constitution was adopted on May 17, 1814. A short war followed, ending with a new agreement between the Norwegian parliament and the Swedish king.

The Convention of Moss was much better for Norway than the Treaty of Kiel. Norway was no longer seen as a Swedish conquest but as an equal partner in a personal union of two independent states. The Norwegian Constitution was kept, with only small changes needed for the union with Sweden. Norway kept its own parliament and separate institutions, except for the shared King and foreign service.

The Norwegian Storting could propose Norwegian laws without Sweden's interference, and these laws would be approved by the shared King as King of Norway. The King sometimes approved laws that Sweden didn't like. As Norway pushed for full independence, the King even approved building forts and naval ships to defend Norway against a Swedish invasion.

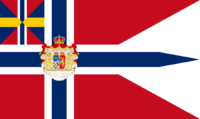

However, Norwegians were still unhappy about being in any union. The Storting often proposed laws to reduce the King's power or to show Norway's independence. The King usually vetoed these laws, but since he could only veto a law twice, it would eventually pass. The 1814 constitution already said Norway would have a separate flag, and the current design was introduced in 1821. The flags of both kingdoms had a union mark added in 1844 to show their equal status. Despite royal objections, this mark was removed from the Norwegian flag in 1898. In 1837, local self-government was introduced in towns and rural areas. A Parliamentary system was put in place in 1884.

The Royal House of Bernadotte tried hard to be a Norwegian royal family as well as a Swedish one. The Royal Palace in Oslo was built during this time. There were separate coronations in Trondheim, as the Constitution required. The royal princes even built a hunting lodge in Norway to spend more private time there. King Oscar II spoke and wrote Norwegian very well.

Full Independence

In 1905, disagreements between the parliament and the King reached a peak over the issue of separate Norwegian consuls for foreign countries. Norway had become a major shipping nation, but Sweden controlled all diplomatic and consulate services. Norwegian businesses needed help abroad, but the Swedes knew little about Norwegian shipping, and there were no consulates in many important shipping cities. The demand for separate Norwegian consuls was very important to the Norwegian parliament and people. The Storting proposed a law to create a separate Norwegian consulate service. King Oscar II refused to sign the law, and the Norwegian government resigned. The King could not form another government that had parliament's support, so on June 7, it was decided that he could no longer function as King of Norway.

In a public vote on August 13, an overwhelming 368,208 votes (99.95%) were in favor of ending the union, with only 184 (0.05%) against. 85% of Norwegian men voted. Women could not vote yet, but Norwegian feminists gathered over 200,000 signatures supporting the dissolution.

During that summer, a Norwegian group had already approached 33-year-old Prince Carl of Denmark, the second son of the Crown Prince of Denmark. The Norwegian parliament had considered other people, but chose Prince Carl partly because he had a son to continue the royal line. More importantly, he was a descendant of independent Norwegian kings and was married to Maud of Wales, the daughter of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom. By choosing a king with British royal ties, Norway hoped to gain Britain's support.

Prince Carl impressed the group with his understanding of Norway's democratic movement. Even though the Norwegian constitution said the Storting could choose a new king if the throne was empty, Carl knew that many Norwegians wanted a republic (a country without a king). Carl insisted he would only accept the crown if the Norwegian people voted for a monarchy in a referendum and if the parliament then elected him king.

On November 12 and 13, in a second public vote, Norwegian voters decided by nearly 79% (259,563 to 69,264) to keep the monarchy instead of becoming a republic. The parliament then offered Carl the Norwegian throne on November 18. The prince accepted that evening, choosing the name Haakon, a traditional name for Norwegian kings. The last king with that name was Haakon VI, who died in 1380.

So, the new king became Haakon VII, King of Norway. His two-year-old son Alexander was renamed Olav and became Crown Prince Olav. The new royal family arrived in the capital, Kristiania (now Oslo), on November 25. Haakon VII was sworn in as King of Norway on November 27.

A Modern Monarchy

The first years of the new Norwegian monarchy were financially difficult. Norway was not a rich country, and money was needed for other things besides a large royal court. Luckily, Prince Carl had agreed to become king only if he didn't have to keep a big court. However, royal travels and the upkeep of royal homes were sometimes neglected after the initial repairs in 1905. For example, Prince Carl was promised a Royal Yacht when he accepted the throne, but he didn't get it until 1947.

Under the 1814 constitution, Haakon had executive power, but he wasn't responsible for using it directly. Haakon, being democratic, mostly focused on ceremonial duties and representing the country, fully accepting the idea of parliamentary democracy. An important event in the early years was in 1928 when the King appointed the first government led by the Norwegian Labour Party. At that time, the Labour Party was quite radical and even wanted to get rid of the monarchy. It was common for the King to ask the previous Prime Minister for advice on who should be the next Prime Minister. In this case, the previous Prime Minister was against giving power to Labour and suggested someone else. However, the King followed the established parliamentary practice and chose Christopher Hornsrud as the first Labour Prime Minister. The Labour Party later removed the idea of ending the monarchy from their goals.

During the German occupation in World War II, the King was a vital symbol of national unity and resistance. His strong refusal to surrender to the Germans was very important for the fighting spirit of the Norwegian people. When Germany demanded that Haakon appoint a government led by Vidkun Quisling, the head of the fascist party, Haakon refused. He told his ministers that neither the people nor the Storting trusted Quisling, and he would rather step down than appoint such a government. This is one of the few times a Norwegian king has directly intervened in the country's politics since the union with Sweden ended. The King's constitutional powers made his position very important and helped the government in exile continue its work with full legitimacy.

After the war, the Norwegian royal family managed to balance being royal with being approachable. After 52 years as Crown Prince, Olav V became King in 1957 when his father died. He was seen as the "people's king," and the widespread sadness when he passed away in 1991 showed how much Norwegians respected him. Even those who wanted a republic lit candles in front of the Palace.

In recent years, the marriages of then Crown Prince Harald in 1968 and Crown Prince Haakon in 2001 caused some debate. However, this had little lasting effect on the monarchy's popularity. While support for the monarchy is not as high as the over 90 percent after the war, it remains stable, mostly above 70 percent. A 2012 poll showed that 93% of people believed the current Monarch was doing a good job for the country.

The King's Role and Powers

Even though the 1814 constitution gives the King important executive powers, these are almost always used by the Council of State (the government) in the King's name.

In modern Norwegian practice, the word "King" in most parts of the constitution now refers to the government (the cabinet led by the Prime Minister), which is accountable to the Storting (parliament) and, ultimately, to the voters. This is different from articles that specifically talk about the monarchy itself.

Immunity and Protection

Article 5 of the Constitution states: The King's person is sacred; he cannot be criticized or accused. The responsibility rests with his Council. This means the King personally cannot be sued or charged in court. While his status as "sacred" was removed in 2018, he still has legal protection.

Article 37 says: The Royal Princes and Princesses shall not personally be answerable to anyone other than the King, or whomever he decides should judge them. This means the Princes and Princesses also have some protection, depending on the King's decision. He could choose for them to be judged by regular courts or judge them himself. This has never been tested.

The Council of State

The Council of State includes the King, the Prime Minister, and other members. All of them are chosen by the King based on the Prime Minister's advice. The Council of State is the Government of Norway and is led by the King. It meets at least once a week, usually on Fridays, with the King in charge. The King can also call extra meetings if urgent decisions are needed. Since 1884, Norway has had a Parliamentary system, which means the government must have the support of the parliament. So, the King's appointment is usually a formality. In practice, the King asks the leader of the political group with a majority in the Storting to form a government. The King relies on advice from the previous prime minister and the President of the Storting for this. The last time the King appointed a new prime minister against the advice of the previous one was in 1928, when he appointed the first Labour government.

Article 12 states: The King himself chooses a Council from among Norwegian citizens who are entitled to vote. ... The King divides the work among the Members of the Council of State, as he thinks best.

Article 30 states: ... Everyone in the Council of State must honestly say what they think, and the King must listen. But the King makes the final decision based on his own judgment. ...

Vetoing Laws

The King must sign all laws for them to become valid. He can refuse to sign any law (veto it). However, if two different Stortings (parliaments) approve the same law, it becomes valid even without the King's signature. The King has not vetoed any law since Norway became fully independent from Sweden.

Article 78 states: If the King agrees to the Bill, he signs it, and it becomes law. If he does not agree, he sends it back to the Storting, saying that he does not find it wise to approve it at this time. In that case, the Bill cannot be presented to the King again by the same Storting. ...

Church of Norway

Until 2012, the King was the official head of the Church of Norway, which is a Lutheran Christian church. Since 2012, the Church has managed itself, but it is still the official state church, and most Norwegians are members. According to the constitution, the Norwegian King must be a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Norway.

Pardoning Criminals

Article 20 states: The King shall have the right in the Council of State to pardon criminals after they have been sentenced. A pardon means forgiving a crime and its punishment. It can be given if new information comes out after someone has been sentenced. A pardon can completely or partly remove a punishment. In practice, the Ministry of Justice handles these requests. The King in Council must formally approve a pardon. In 2004, 51 pardon requests were approved, and 274 were denied. In impeachment cases, the King cannot pardon someone without the Storting's approval.

Appointing Officials

Article 21 states: The King shall choose and appoint, after talking with his Council of State, all important civilian and military officials. The King makes these appointments after getting advice and agreement from the Council of State.

Dismissing the Government

Article 22 states: The Prime Minister and the other Members of the Council of State, along with the State Secretaries, can be dismissed by the King without a court judgment, after he has heard the Council of State's opinion on the matter.

Royal Orders

Article 23 states: The King may give awards to anyone he wishes, as a reward for excellent service... Norway has two main royal orders: the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav and the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit. The King also gives out several other important medals for various achievements.

Role in War

Article 25 states: The King is Commander-in-Chief of the land and naval forces of the Realm. The King is also the Commander-in-Chief of the Norwegian Air Force, even though it wasn't mentioned in 1814 because it didn't exist then.

Article 26 states: The King has the right to call up troops, to fight to defend the Realm and to make peace, to sign and cancel agreements, to send and receive diplomats. The armed forces see the King as their highest commander. However, the elected government actually has full control of the armed forces. Norwegian Kings have traditionally received extensive military training and often had careers in the armed forces before becoming King. During World War II, the King played a more active role in decisions. While the government still had the final say, the King's advice was very important. During the invasion, when the Germans demanded Norway's surrender, King Haakon VII told the government he would step down if they accepted. In 1944, Crown Prince Olav was appointed Chief of Defence because of his military leadership skills.

Coronation and Oath

In ancient Norwegian history, a monarch was installed by acclamation, a ceremony where the king promised to follow the laws, and the leaders promised loyalty to him. The first coronation in Norway happened in Bergen in 1163 or 1164. For a long time, both ceremonies were used. This showed that the king received power from both the noblemen and the church. Coronations also symbolized that the king held the kingdom as a gift from St. Olav, the eternal king of Norway. The last acclamation took place at Akershus Castle in 1648. The last medieval coronation in Norway was on July 29, 1514. During the time of absolute monarchy (1660–1814), Norway's kings were crowned in Copenhagen.

Today, the King still goes through a ceremony similar to the old acclamation when he takes an oath to the Constitution in the Storting. The Norwegian Constitution of 1814 said that all Norwegian coronations from then on should happen in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. This reconnected the monarchy to the sacred church where kings were buried. The part of the constitution about coronations was removed in 1908. When King Olav V became King in 1957, he still wanted a church blessing for his reign. So, the Benediction of the King was introduced. This is a simpler ceremony, but it still takes place in Nidaros Cathedral with the Royal Regalia (crown jewels) present. The regalia are kept in the old Archbishop's Palace in Trondheim. King Harald V and Queen Sonja also received this blessing in 1991.

The Constitution requires the new King to immediately take an oath before the Storting (or, if parliament is not meeting, before the Council of State and then again before the Storting when it meets). The oath is: "I promise and swear that I will govern the Kingdom of Norway in accordance with its Constitution and Laws; so help me God, the Almighty and Omniscient."

Succession to the Throne

The order of succession to the Norwegian throne has followed absolute primogeniture since 1990. This means the oldest child, regardless of gender, inherits the throne. This rule is described in Article 6 of the Constitution of Norway. Only people descended from the reigning monarch can become King or Queen. If the royal line ever ends, the Storting can elect a new king or queen.

Royal Finances

The King, Queen, Crown Prince, and Crown Princess do not pay taxes, and their personal money details are not made public. Other members of the royal family lose this privilege when they get married. It is believed that only the King has a significant personal fortune.

The royal farms make some money, but this is always put back into the farms themselves.

In Norway's 2010 state budget, about 142.5 million Norwegian kroner was given to the Royal Household. An additional 16.5 million was given to the monarchs for their personal use. Another 20.9 million was set aside for repairing royal properties. In 2010, the Royal Household said that King Harald V's personal wealth was close to 100 million Norwegian kroner. In the late 1990s, 500 million Norwegian kroner was set aside for major renovations of the royal residences, which are still ongoing. The restoration of the Royal Palace in Oslo went over budget because the building's condition was much worse than expected. However, the high cost was criticized in the media.

Royal Homes

The royal family has several homes across the country. All official residences are partly open to the public.

Current Royal Homes

The Royal Palace

The Royal Palace in Oslo is the main official home of the King. It was built in the first half of the 19th century for the Norwegian and Swedish king Charles III (who reigned from 1818–1844). Today, it is the official residence of the current Norwegian Monarch.

Gamlehaugen

Gamlehaugen is a large house and estate that serves as the monarch's home in Bergen. It was originally the home of Prime Minister Christian Michelsen and became the royal family's residence in 1927.

Stiftsgården

Stiftsgården in Trondheim is a large wooden townhouse. The royal family has used it since the early 1800s. This building has been the main place for celebrations during coronations, blessings, and weddings, which traditionally happen in the Nidaros Cathedral.

Ledaal

Ledaal is a large manor house in Stavanger. It used to belong to the important Kielland family. Since 1936, it has been owned by the Stavanger Museum and became a royal residence in 1949.

Other Royal Homes

Bygdøy Royal Estate, the official summer home, is in Oslo. Bygdøy has been undergoing major repairs and was not used regularly since King Harald V became King in 1991. The repairs finished in 2007, and the royal family has used it often since then. The Royal Lodge or Kongsseteren is in Holmenkollen. The Royal Family uses it for Christmas and the Holmenkollen Ski Festival every year. Oscarshall palace, a pleasure palace, is also in Oslo but is rarely used.

The Crown Prince and Crown Princess live at Skaugum Manor in Asker municipality, just outside Oslo. The three princesses of Norway live on estates in Oslo, Fredrikstad, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Both Skaugum and Bygdøy Royal Estate are working farms that produce grain, milk, and meat. The money earned is put back into the farms. In 2004, the King handed over the management of farming activities at Bygdøy to the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History.

The King owns a royal yacht called HNoMY Norge. It is operated and maintained by the Royal Norwegian Navy and is used for both official and private trips in Norway and abroad. The Norwegian Railway Museum also has a royal train carriage.

The royal family also has several private holiday homes.

Past Royal Homes

- Paléet: A grand townhouse that served as a royal residence between 1801 and 1849 before the Royal Palace was built.

- Akershus Fortress: This castle in Oslo was turned into a palace by King Christian IV during the union between Denmark and Norway.

- Bergenhus Fortress: Originally, this medieval castle was a royal residence, while Sverresborg defended the city.

- Tønsberg Fortress: The castle in Tønsberg was used as a home by several kings, including Håkon V Magnusson, who was the last king of Norway before the Kalmar Union.

- Various Kongsgård estates were used by Norwegian kings during the Viking Age and early Middle Ages. These include important estates like Alrekstad, Avaldsnes Kongsgård estate, and the Oslo Kongsgård estate.

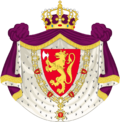

Royal Coat of Arms

The Coat of arms of Norway is one of the oldest in Europe. It serves as both the national coat of arms and the coat of arms for the Royal House. This is because it started as the coat of arms for the kings of Norway in the Middle Ages.

Håkon the Old (1217–1263) used a shield with a lion. The first record of the colors of the arms is from the King's Saga, written in 1220.

In 1280, King Eirik Magnusson added a crown and a silver axe to the lion. The axe is the martyr axe of St. Olav, the weapon used to kill him in the battle of Stiklestad in 1030.

The design of the Norwegian arms has changed over the years to fit different styles. In the late Middle Ages, the axe handle became longer and looked more like a halberd. The handle was often curved to fit the shape of shields and coins at the time. The halberd was officially removed, and the shorter axe was brought back by royal order in 1844, when an official design was first created. In 1905, the official design for royal and government arms was changed again, going back to the medieval style with a triangular shield and a more upright lion.

The coat of arms of the royal house and the Royal Standard use the lion design from 1905. The oldest known picture of the Royal Standard is on Duchess Ingebjørg's seal from 1318. The design used as the official coat of arms of Norway is slightly different and was last approved by the King on May 20, 1992.

When used as the Royal coat of arms, the shield has the symbols of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav around it. It is also surrounded by a royal ermine robe and topped with the crown of Norway.

The Royal coat of arms is not used very often. Instead, the King's monogram (a design made from his initials) is widely used, for example, on military badges and coins.

See also

In Spanish: Monarquía de Noruega para niños

In Spanish: Monarquía de Noruega para niños

- List of Norwegian monarchs

- Norwegian royal family

- Royal coronations in Norway

- House of Glücksburg

- Politics of Norway

- Republicanism in Norway

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |