Viking expansion facts for kids

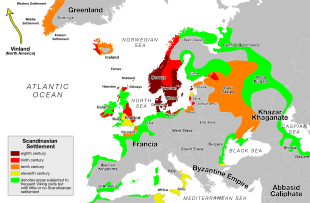

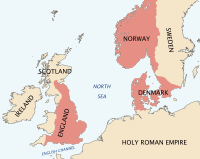

Viking expansion was a big historical movement. It saw Norse explorers, traders, and warriors, often called Vikings, travel across much of the North Atlantic. They sailed as far south as North Africa and as far east as Russia. They even reached Constantinople and the Middle East through the Mediterranean Sea. Vikings acted as raiders, traders, settlers, and even hired soldiers.

To the west, Vikings led by Leif Erikson reached North America. They set up a short-lived settlement in what is now L'Anse-aux-Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada. More lasting Norse settlements were made in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Russia, Great Britain, Ireland, and Normandy.

Historians sometimes debate if the word "Viking" means all Norse settlers or just those who went on raids.

Contents

Why Did the Vikings Expand?

Historians have many ideas about why the Vikings started to expand.

One idea is that Viking men needed to find women from other lands. Some powerful Viking men had many wives. This might have meant fewer women for other men. So, some Viking men might have taken risks to gain wealth and power. This could help them find partners. Vikings sometimes bought or took women from other places.

Another idea is that Vikings wanted revenge. They might have been angry at Europeans for past attacks. For example, Charlemagne forced Saxon pagans to become Christians. But the first Viking raids were not on Charlemagne's kingdom. They attacked Christian monasteries in England. These places were rich and had lots of food. So, some historians think Vikings raided them for wealth, not for religious reasons.

Some people think the Viking population grew too big for their homeland. This might have been true for western Norway. But it's unlikely the rest of Scandinavia had famines.

Another theory is about "youth bulge." This means many young men needed land and wealth. Often, the oldest son inherited everything. So, younger sons had to leave home or go on raids to find their own fortune. Some historians believe Vikings left because they wanted more land, not because they had to.

However, there is no clear proof of a big population rise or food problems. It's also not clear why they went overseas. They could have settled in the huge forests of Scandinavia. But perhaps going by sea was easier or more profitable.

It's also possible that old trade routes became less profitable. Trade in Europe might have slowed after the Roman Empire fell. The expansion of Islam also changed trade routes. When Vikings started expanding, Mediterranean trade was very low. The Vikings opened new trade routes. They took control of markets that others, like the Frisians, used to control.

A main goal of Viking expansion was to get and trade silver. Places like Bergen and Dublin are still important silver centers. The Galloway Hoard is an example of Viking-age silver found for trading.

Who Settled Where?

Viking settlements in Ireland and Great Britain might have been mostly men. But some graves show an equal number of men and women. This is still debated by archaeologists. Old texts say that Irish and British women went with Vikings to Iceland. Genetic studies in the Western Isles and Isle of Skye also show that Viking men settled there. They often had children with local women.

However, not all Viking settlements were just men. Genetic studies in the Shetland Islands suggest that Viking families, including women, moved there. This might be because Shetland was closer to Scandinavia. So, it was easier for families to move there. Farther places might have been settled more by groups of single men.

Viking Journeys to the British Isles

Vikings were very active in the British Isles. They raided and settled in many areas.

England

The first recorded Viking raid in England was around 789 AD. Three ships of "Northmen" landed in Dorset. They killed a local official who thought they were merchants. In 793, Vikings attacked the church on Lindisfarne. They killed monks and took treasures. The monks later fled Lindisfarne in 875.

In 794, a small Viking fleet attacked a monastery at Jarrow. The Vikings faced strong resistance. Their leaders were killed. The raiders escaped but their ships were beached. Locals then killed the crews. After this, Vikings focused on Ireland and Scotland for about 40 years.

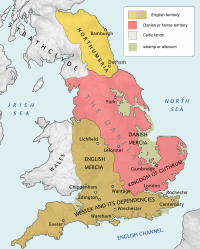

In 865, many Viking groups joined together. They formed a large army and landed in East Anglia. This force was called the Great Heathen Army. It was led by Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan Ragnarsson.

The army moved through England and captured York (Jorvik). In 871, another Danish force joined them. In 875, the Great Heathen Army split. Halfdan's group settled in Northumbria. They farmed the land, creating the area known as the Danelaw.

Most English kingdoms were weak. But King Alfred the Great of Wessex defeated a Viking army in 878. Treaties were made, setting boundaries between English and Viking lands. They also aimed for peace. But fighting continued. Alfred and his successors slowly pushed back the Vikings. They eventually retook York.

New Vikings arrived in England in 947. Eric Bloodaxe captured York. The Viking presence continued under the Danish king Canute the Great (1016–1035). After him, arguments over who would rule weakened the Danish hold.

In 1066, the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada tried to become King of England. But he was defeated and killed by Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Harold Godwinson then died when William the Conqueror defeated the English at the Battle of Hastings. William became king of England.

Later, Danish kings tried to invade England again. But these attempts failed. The last serious Danish invasion plan was in 1085. Some raids happened later, but they were not for conquest. These raids marked the end of the Viking Age in England.

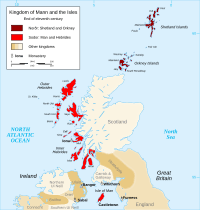

Scotland

The monastery at Iona was first raided in 794. It had to be abandoned later after many attacks. Scandinavian presence in Scotland grew in the 830s.

Islands north and west of Scotland were heavily settled by Norwegian Vikings. Shetland, Orkney, and the Hebrides came under Norse control. Sometimes they were part of Norway. Other times they were separate kingdoms. Shetland and Orkney became part of Scotland much later, in 1468.

Wales

Viking settlements were not as common in Wales as in other British Isles nations. This is likely because Welsh kings, like Rhodri the Great, had strong armies. So, Vikings could not set up states in Wales. They mostly raided and traded.

Danes raided Anglesey in 854. But Welsh records say Rhodri the Great won a big victory. He killed the Danish leader, King Gorm. Rhodri won two more battles in 872. The Vikings in Anglesey were defeated again.

In 893, Viking armies were chased by English and Welsh forces. They were defeated at the Battle of Buttington.

Viking Names in Wales

Many coastal names in Wales today come from the Vikings. For example, the English name Anglesey comes from Scandinavia. So do names like Caldey Island and Flat Holm. Wales' second largest city, Swansea, gets its English name from a Viking trading post. It was founded by Sweyn Forkbeard. The original name meant "Sweyn's island." Worm's Head comes from a Viking word for "snake" or "dragon." Vikings thought the island looked like a sleeping dragon.

Cornwall

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that Danes raided Charmouth in 833 AD. They destroyed Lydford in 997 AD. From 1001 to 1003 AD, they occupied Exeter.

The Cornish people were controlled by King Æthelstan of England in 936. The border was set at the River Tamar. But the Cornish remained somewhat independent. They were fully joined with England after the Norman Conquest.

Ireland

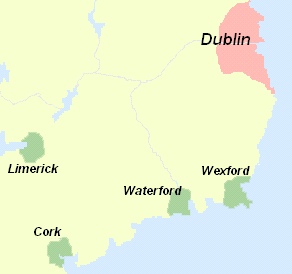

In 795, small Viking groups started raiding monasteries along the Irish coast. In 821, Vikings plundered Howth. They took many women captive. From 840, Vikings built fortified camps called longphorts. They stayed in Ireland over winter. Their attacks grew bigger. They hit large monasteries like Armagh and Clonmacnoise. They also plundered ancient tombs.

In 853, Viking leader Amlaíb Conung became the first king of Dublin. He ruled with his brothers. There was often fighting between Vikings and Irish. Also, two groups of Vikings fought each other. Vikings sometimes allied with Irish kings against rivals. In 866, Áed Findliath burned all Viking camps in the north. Vikings never settled there permanently. Vikings were driven from Dublin in 902.

They returned in 914. Over the next eight years, Vikings won big battles. They regained Dublin. They founded settlements at Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Limerick. These became Ireland's first large towns. They were important trading centers. Viking Dublin was the biggest slave port in western Europe.

These Viking areas became part of the many kingdoms in Ireland. Vikings married Irish people. They adopted parts of Irish culture. They became known as the Norse-Gaels. Some Viking kings of Dublin also ruled other areas.

In 980, Máel Sechnaill Mór defeated the Dublin Vikings. He forced them to obey him. Later, Brian Boru took control of Viking areas. He became High King of Ireland. The Dublin Vikings rebelled twice. But they were defeated in battles. After the battle of Clontarf in 1014, the Dublin Vikings could no longer threaten the most powerful Irish kings.

Viking Journeys to Europe

Vikings also traveled and settled across mainland Europe.

Normandy

The name Normandy itself comes from "Northmannia." This means "Land of The Norsemen."

Vikings started raiding the Frankish Empire in the mid-9th century. They attacked many towns like Rouen and Paris. The Frankish kings could not stop them. So, they paid Vikings large amounts of silver and gold. But the Vikings always returned for more.

The Duchy of Normandy was created for the Viking leader Rollo. He had attacked Paris. In 911, Rollo agreed to serve the Frankish king Charles the Simple. This agreement was called the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. Rollo became the first Norman Count of Rouen. He also agreed to be baptized. In return, Rollo legally gained the land he and his Vikings had already conquered.

Rollo's descendants and followers adopted the local languages. They married local people. They became the Normans. They spoke a mix of Scandinavian and French. The Norman language had many words from Old Norse. Especially words about sailing. Many place names in Normandy still show Nordic influence.

Rollo's descendant, William the Conqueror, became King of England in 1066. He defeated Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings. As king, William kept Normandy. This led to many disputes between English and French kings.

West and Middle Francia

West Francia and Middle Francia suffered more from Viking raids than East Francia. The reign of Charles the Bald saw some of the worst raids. He tried to stop them by building fortified bridges. He also created a royal cavalry army.

However, the Bretons allied with the Vikings. Many leaders died fighting Vikings. Vikings also used civil wars in Aquitaine to their advantage. They settled at the mouth of the Garonne River. Some dukes of Gascony died defending Bordeaux from Vikings.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Vikings raided towns in the Low Countries. These towns were along the coast and rivers. Vikings did not settle in huge numbers. But they set up long-term bases. They were even recognized as lords in some places. They had bases at Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, Taillebourg, and Bayonne. They also had bases on the River Seine in what became Normandy.

Antwerp was raided in 836. Later, there were raids on Ghent, Kortrijk, and other cities. They also raided areas around the Meuse and Rhine rivers. Raids were launched from bases like Asselt and Walcheren. The trading center of Dorestad is thought to have declined after Viking raids.

One important Viking family in the Low Countries was Rorik of Dorestad and his brother Harald. Around 850, Lothair I recognized Rorik as ruler of most of Friesland. Rorik died before 882.

Viking treasures, mostly silver, have been found in the Low Countries. A large treasure found in Wieringen in 1996 might be linked to Rorik. This suggests a permanent Viking settlement there.

Around 879, Godfrid arrived with a large force. They terrorized the Low Countries. Using Ghent as a base, they attacked many cities. Godfrid controlled most of Frisia from 882 to 885. He became a vassal to Charles the Fat. Godfrid was killed in 885. After this, Viking rule in Frisia ended.

Viking raids continued for over a century. The last attacks were in Tiel in 1006 and Utrecht in 1007.

Iberian Peninsula

Compared to other parts of Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) had fewer Viking attacks. Both Christian and Muslim armies often defeated the Vikings there.

Most of what we know about Vikings in Iberia comes from old writings. These are often written much later and can be unclear. There is little archaeological proof yet. Viking activity in Iberia seems to have started around the mid-9th century. It was an extension of their raids in Frankia. But there is no proof of long-term trading or settlement.

The most important event was a raid in 844. Vikings entered the Garonne river. They attacked Galicia and Asturias. When they attacked A Coruña, the army of King Ramiro I of Asturias heavily defeated them. Many Vikings died. Seventy of their longships were captured and burned.

They then went south, raiding Lisbon and Seville. The Viking raid on Seville was a big attack.

From 859 to 861, another series of Viking raids happened. After raiding northern Iberia and Al-Andalus, Vikings also raided other Mediterranean places. This might have included Italy and Constantinople.

Evidence for Viking activity in Iberia disappears after the 860s. It reappears in the 960s–970s. Various sources show convincing evidence of Viking raids then.

Mouse bones found in Madeira suggest Vikings came there too. They brought mice with them. This was long before Portugal settled the island.

Minor Viking raids continued into the early 11th century. As the Viking Age ended, Scandinavians still visited Iberia. They were often on their way to the Holy Land for pilgrimages or crusades.

Italy and Sicily

Around 860, records show Vikings from Frankia went to Iberia and then to Italy.

Three or four 11th-century Swedish runestones mention Italy. They remember warriors who died in "Langbarðaland," the Old Norse name for southern Italy. These men were likely Varangians, hired soldiers fighting for the Byzantine Empire. Varangians might have fought against Arabs in Italy as early as 936.

Later, some Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles joined the Norman conquest of southern Italy. Harald Hardrada, who became king of Norway, was involved in the Norman conquest of Sicily. This was between 1038 and 1040. He fought under William Iron Arm. Edgar the Atheling, who left England in 1086, also went there.

Islamic Levant

Harald Hardrada also served the Byzantine emperor in Palestine. He raided North Africa and the Middle East. He went as far east as Armenia and to Sicily in the 11th century. This is told in his saga.

Evidence of Norse journeys to Arabia and Central Asia is found on runestones. These stones were put up in Scandinavia by relatives of Viking adventurers. Several mention men who died in "Serkland" (the land of the Saracens, or Arabs).

In the Eastern Mediterranean, the Norse (called Rus') were seen more as "merchant-warriors." They were mostly known for trade. One detailed account of a Viking burial comes from Ahmad ibn Fadlan. Sometimes, this trading relationship turned violent. Rus' fleets raided the Caspian Sea at least three times.

Eastern Europe

Vikings settled coastal areas along the Baltic Sea. They also settled along rivers in Russia. These included Staraya Ladoga and Novgorod. They used major waterways to reach the Byzantine Empire.

The Varangians were Scandinavians who moved east and south. They traveled through what is now Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. This was mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. They traded, settled, pirated, and worked as hired soldiers. They traveled along river systems. They reached and settled at the Caspian Sea and in Constantinople.

The Varangians were asked by Slavic tribes to come and bring order. The tribes were fighting each other. Rurik, a Varangian leader, united the tribes. He set up trading towns along the Volga and Dnieper Rivers. These were perfect for trade with the Byzantine Empire. Rurik's followers conquered and united towns along these rivers. They established the Rus' Khaganate. Over time, the Varangians mixed with the local people. By the end of the 12th century, a new people, the Russians, had emerged.

Iran and the Caucasus

Ingvar the Far-Travelled led trips to Iran and the Caucasus. This was between 1036 and 1042. His journeys are recorded on the Ingvar runestones.

Around 1036, Varangians appeared near Bashi on the Rioni River. They wanted to set up a permanent Viking settlement in Georgia. The The Georgian Chronicles say 3,000 men traveled from Scandinavia. They went through Russia, down the Dnieper River, and across the Black Sea. King Bagrat IV of Georgia welcomed them. He took some into the Georgian army. Several hundred Vikings fought for Bagrat in 1042.

Viking Journeys to the North Atlantic

Iceland

Iceland was discovered by Naddodd. He was sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands but got lost. He drifted to Iceland's east coast. Naddodd named it Snæland (Snowland). Another sailor, Garðar Svavarsson, also accidentally drifted there. He found it was an island and named it Garðarshólmi. He stayed for the winter. The first Scandinavian to sail there on purpose was Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson. He stayed one winter. He saw ice in the fjords and named the island Ísland (Iceland).

Iceland was first settled around 870. The first permanent settler is usually thought to be Ingólfr Arnarson. He threw two carved pillars overboard. He vowed to settle where they landed. He sailed until the pillars were found in the southwest. He settled there around 874. He named the place Reykjavík (Bay of Smokes) because of the steam from the earth.

Greenland

In 985, Erik the Red is believed to have discovered Greenland. He was exiled from Iceland for murder in 982. Three years later, in 986, Erik the Red returned. He had 14 ships (out of 25 that started). Norse settlers, including Erik, colonized two areas on Greenland's southwest coast around 986. The land was not ideal for farming. But settlers arrived during a warm period. They could grow crops like rye and barley. They also raised sheep and cattle. Their main export was walrus ivory. They traded it for iron and other goods. Greenland became part of Norway in 1261.

By the 13th century, the population might have reached 5,000 people. They lived in two main settlements. These settlements were organized around religion. They had about 250 farms and 14 churches. One church was a cathedral. The climate later became colder (the Little Ice Age). In 1379, the northern settlement was attacked by the Skræling (Norse word for Inuit). Crops failed and trade declined. The Greenland colony slowly disappeared. By 1450, it had lost contact with Norway and Iceland.

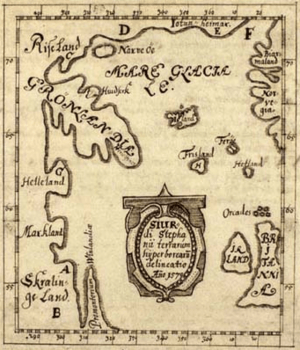

North America

A Norwegian ship captain named Bjarni Herjólfsson first saw part of North America around 985. He was blown off course sailing to Greenland. Later trips from Greenland, some led by Leif Erikson, explored areas to the west. They looked for large timber for building. Greenland only had small trees. Vikings regularly visited Ellesmere Island and Skraeling Island. They hunted and traded with Inuit groups.

A short-lived settlement was built at L'Anse-aux-Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. Wood from the buildings was dated using a solar storm in 993. Tree rings showed that logs were cut in 1021. This means the settlement was used at that time.

There is also proof of Vikings meeting Native Americans. Vikings called them Skræling (meaning "barbarians" or "weaklings"). Fighting happened between Natives and Vikings. Natives had bows and arrows. But they also traded goods. However, conflicts led to the Vikings leaving the area.

The Greenlanders called the new land Vinland. It's unclear if this meant "wine-land" or "meadow-land." Without official support, Viking attempts to settle failed. There were too many natives for the Greenlanders to conquer. So, they went back to Greenland.

Svalbard

Vikings might have discovered Svalbard as early as the 12th century. Old Norse stories mention a land called Svalbarð, meaning "cold shores." This land might also have been Jan Mayen or part of eastern Greenland. The first definite discovery of Svalbard was by Willem Barents in 1596.

Genetic Clues from Viking Expansion

Studies of genetic diversity help confirm what archaeologists find about Viking expansion. They show where people came from and how they moved. They also show how people mixed between different regions. But later migrations make it hard to know exactly what ancient genetics looked like.

Genetic evidence suggests Vikings were not just raiders. Some research shows both male and female genetic markers. This points to settlement, not just raiding. However, other studies show more male genetic markers than female. This suggests more men settled than women.

Tracing Ancestry with DNA

Y-chromosome haplotypes show male family lines. mDNA shows female family lines. Together, these help trace a people's genetic history. They show how men and women moved over time.

Icelanders are often seen as having pure ancient Nordic genes. About 75% to 80% of their male ancestry is from Scandinavia. The rest is from Scotland and Ireland. For female ancestry, only 37% is from Scandinavia. The other 63% is mostly Scottish and Irish. Iceland has good records of family lines. This helps scientists study Viking genetics.

Common DNA Groups

Haplogroup I-M253 is the most common male DNA group in Scandinavia. It is found in 35% of men in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. It is also common in Finland. It is found along the Baltic and North Sea coasts.

Haplogroup R1b is common in Western Europe. But it is not clearly linked to Vikings. There are signs that a specific type, R-L165, might have been brought to Great Britain by Vikings. But this is still being studied.

C1 Haplotype

The mitochondrial C1 is mostly found in East Asia and America. It developed before people crossed the Bering Sea. But this female DNA group was found in some Icelandic samples. It has been in Iceland for at least 300 years. This suggests genetic exchange between Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland.

Surname History and DNA

Combining Y-haplotypes with surname histories can help understand old populations better. This stops recent migrations from hiding the true historical picture.

Cys282Tyr Mutation

Cys282Tyr (C282Y) is a gene change linked to a condition called hereditary hemochromatosis. This mutation likely happened about 600 to 800 years ago. Its spread in Europe shows it started in Southern Scandinavia. It then spread with Viking expansion. Because of this, C282Y is common in Great Britain, Normandy, and Southern Scandinavia. It has been found in almost every population that had contact with Vikings.

See also

In Spanish: Expansión vikinga para niños

In Spanish: Expansión vikinga para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |