History of Ireland (795–1169) facts for kids

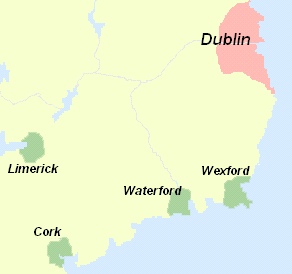

The history of Ireland from 795 to 1169 is a time when Viking raiders first arrived and later settled along the coast. These Vikings built the first big towns in Ireland, like Dublin, Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick.

During this period, Ireland was made up of many small, independent kingdoms called túatha. Different groups of Irish kings tried to gain control over the whole island. For the first 200 years, the main struggle was between two powerful families, the Uí Néill, from the north and south of Ireland. However, the king who came closest to ruling all of Ireland was Brian Boru. He was the first high king during this time who was not from the Uí Néill family.

After Brian Boru died at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, the political situation became more complicated. Many different clans and families fought to become the high king. Brian's family couldn't keep the whole island united. This fighting over land eventually led to the Normans arriving in Ireland in 1169, led by Richard de Clare.

Contents

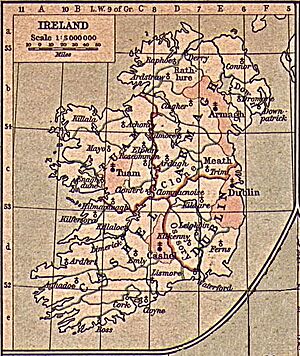

Ireland's Political Map Around 800

Around the year 800, Ireland was mostly Gaelic in its society, culture, and language. People lived in farming communities. The only larger settlements were monastic towns, which were important for religious life, culture, and even business and politics. Christianity had spread across the island by the early 9th century.

Historians often talk about Ireland being divided into five main areas: Ulaid (Ulster), Connachta (Connacht), Laigin (Leinster), Mumu (Munster), and Mide (Meath). While this wasn't exactly how things were in 800, it helps to understand the different regions. If you combine Leinster and Meath, it's similar to the four modern provinces of Ireland.

The Uí Néill family was the most powerful in Ireland. They had two main branches: the "Northern Uí Néill" and the "Southern Uí Néill." The Northern Uí Néill controlled the northwest, while the Southern Uí Néill ruled the central region of Mide.

Other important kingdoms included:

- Ulaid: In the east, near the river Bann.

- Laigin: In the southeast, where the Uí Dúnlainge family was strong.

- Kingdom of Osraige: In the area of modern County Kilkenny.

- Munster: In the south, ruled by the Eóganachta family.

- Connacht: In the west, where the Uí Briúin family was in charge.

The First Viking Age (795–902)

Early Viking Raids

The first time Vikings were recorded in Irish history was in 795. They looted Lambay Island, off the coast of Dublin. More raids followed in 798 and 807. These early attacks were usually small and quick.

These raids interrupted a time of great Christian Irish culture. For the next 200 years, Vikings would regularly attack monasteries and towns across Ireland. Most early raiders came from western Norway. They sailed to the Shetland and Orkney islands, then down the coast of Scotland to Ireland. They even reached the Skellig Islands off County Kerry.

Some Viking leaders are mentioned in old Irish records, like Saxolb (837), Turges (845), and Agonn (847).

Irish Kings Fight Back

Áed Oirdnide became the Uí Néill King of Tara in 797. He tried to strengthen his power across Ireland. Historians believe that there were no major Viking attacks during his reign after 798, though the old records don't say he fought the Vikings directly.

Áed was connected to the important monastery at Armagh. His rivals supported the monastery of Columba. After several Viking raids on Iona, the Columban monks built a new monastery at Kells, which was a royal site.

Rivalry Between North and South

Fedelmid mac Crimthainn became king of Munster in 820. He wanted to expand his power to challenge the Uí Néill. He launched raids into Mide and Connacht. In 827, he even met with the Uí Néill overking, Conchobar mac Donnchada, to discuss peace. This shows how powerful Feidlimid was becoming.

Niall Caille became the Uí Néill overking in 833. He was the first Uí Néill king mentioned in records fighting Vikings, defeating them in Derry that same year. Niall also tried to expand Uí Néill power south, leading to more conflict with Feidlimid. In 841, Niall defeated Feidlimid in battle. After this, no southern king challenged the north as much for about 150 years.

More Viking Raids and First Settlements

Viking raids became more frequent and intense after 821. The Vikings started building fortified camps called longports along the Irish coast. They would stay in Ireland over winter instead of going back to Scandinavia or British bases. The first known longports were at Linn Dúachaill (Annagassan) and Duiblinn (near present-day Dublin).

Vikings also started moving inland, often using rivers like the Shannon, before returning to their coastal bases. Their raiding parties grew larger. In 837, records mention a fleet of 60 longships on the Liffey, carrying 1,500 men. These larger forces attacked important monastic towns like Armagh, Glendalough, and Clonmacnoise.

One Viking leader, Thorgest, is mentioned in some later records as attacking Connacht, Mide, and Clonmacnoise in 844. He was captured and drowned by Máel Sechnaill mac Maíl Ruanaid, the King of Mide. However, historians are not sure if Thorgest really existed as described. Stories about him and his wife being a witch might have been propaganda written much later to make Vikings seem evil.

In 853, Olaf, described as a "son of the king of Lochlann," arrived in Ireland. Lochlann likely referred to a Viking settlement in the Western Isles of Scotland. Olaf took charge of the Vikings in Ireland, possibly sharing power with his relative Ivar. Ivar's descendants, the Uí Ímair, would be important in Irish politics for the next two centuries.

Changing Alliances and Power Struggles

From the mid-9th century, Vikings started making alliances with Irish rulers. For example, Cerball mac Dúnlainge, King of Osraige, sometimes allied with Olaf and Ivar against Máel Sechnaill. These alliances were not permanent, and sides often changed.

Máel Sechnaill had more success than earlier high kings in controlling the south of Ireland. He forced Munster and Osraige to accept his rule. He was even called "king of all Ireland" when he died. However, he faced strong opposition from other Irish kings who allied with the Norse of Dublin.

Áed Findliath became the leading king of the Northern Uí Néill. He had some success against the Norse, burning their longports in the north in 866. The Vikings never managed to build permanent settlements in the north of Ireland.

The last report of Olaf is in 871, and Ivar died in 873. After they were gone, there was a lot of fighting among the Norse in Ireland. In 902, Irish kings Máel Finnia mac Flannacain and Cerball mac Muirecáin joined forces and drove the Vikings out of Dublin.

Why Vikings Failed to Conquer Ireland

The Vikings were very good at invading other countries like England and France. Ireland seemed like an easy target because it had so many small, divided kingdoms. Irish kings sometimes even allied with Vikings to weaken their rivals.

However, Ireland's decentralized system actually made it hard for Vikings to conquer. If a king was defeated, he was easily replaced, and the Vikings would have to start all over again. There were over 150 different kingdoms, making it almost impossible for Vikings to gain full control of the land.

Impact on Irish Scholars

Historians discuss how Viking raids affected Irish scholarship. Irish scholars were famous for writing poetry, religious texts, and law books. Kings often supported these scholars. When the Vikings arrived, this support might have lessened as kings focused on fighting or trading with Vikings.

At the same time, many Irish scholars, known as peregrini, became more active in Europe, especially at the court of Charlemagne. Famous Irish scholars like John Scottus Eriugena and Sedulius Scottus became very influential, teaching theology and philosophy. It's possible that the Viking raids encouraged these scholars to seek work elsewhere, which helped spread Irish culture across Europe.

The Second Viking Age (914–980)

After being forced out of Dublin in 902, Ivar's descendants, known as the Uí Ímair, remained active around the Irish Sea. In 914, a new Viking fleet arrived in Waterford Harbour, and the Uí Ímair soon followed, taking control of Viking activities in Ireland again. Ragnall arrived in Waterford, while Sitric landed in Leinster.

Niall Glúndub became the Uí Néill overking in 916. He fought against Ragnall but without a clear winner. The men of Leinster attacked Sitric but were heavily defeated in the Battle of Confey in 917. This victory allowed Sitric to take back control of Dublin for the Norse. Ragnall left Ireland in 918 and became king of York in England.

With Sitric in Dublin and Ragnall in York, a strong connection formed between Dublin and York, influencing both England and Ireland for the next 50 years.

A new and more intense period of Viking settlement began in Ireland in 914. Between 914 and 922, the Norse established towns like Waterford, Cork, Dublin, Wexford, and Limerick. Modern excavations in Dublin and Waterford have uncovered a lot about the Viking history of these cities. Many Viking burial stones, called the Rathdown Slabs, have been found in South Dublin.

The Vikings founded many other coastal towns. After several generations, Irish and Norse people mixed and intermarried, creating a group known as Norse-Gaels or Hiberno-Norse. You can still see Norse influence in some Irish king names (like Magnus or Sitric) and even in the DNA of some people in these coastal cities today. Studies suggest that Viking settlements might have had a Scandinavian ruling class, but most of the people living there were native Irish.

Niall Glúndub attacked Dublin in 919, but Sitric's forces defeated him at the battle of Islandbridge. Niall and many other Irish leaders were killed. Dublin was secured for the Norse. Sitric then left for York in 920 and became its ruler. His relative, Gofraid, took control of Dublin.

Gofraid was a Viking raider, but there were signs that the Norse were changing. During a raid on Armagh in 921, Gofraid "...spared the prayerhouses... ...and the sick from destruction." This was different from the earlier raiders. Dublin also launched strong campaigns in eastern Ulster from 921 to 927, trying to create a Scandinavian kingdom there.

Dublin's plans in Ulster were stopped by Muirchertach mac Néill, Niall Glúndub's son. Muirchertach was a very successful general. He also forced other kingdoms to submit, even capturing the king of Munster in 941.

When Sitric died in 927, Gofraid tried to become king of York but was driven out by Athelstan. He returned to Dublin, which the Vikings of Limerick had taken. Gofraid retook the city, but the fight with Limerick continued after his death in 934. His son, Amlaíb, defeated Limerick in 937. That same year, Amlaíb went to Northumbria and allied with Scottish kings. Athelstan defeated them at Brunanburh in 937. However, after Athelstan's death in 939, Amlaíb became king of York. Another relative, Amlaíb son of Sitric, also became important.

Congalach mac Máel Mithig, also known as Cnogba, became the Uí Néill overking in 944. He was the first from his family to be called "High King" since the early 8th century. In 944, he attacked Dublin. When Amlaíb Cuaran returned to Ireland, he became ruler of Dublin and allied with Congalach against a rival Uí Néill king. This alliance didn't last long. Congalach was killed in 956 in a battle against an alliance of Dublin and Leinster.

In 980, Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill became high king. That same year, he defeated the forces of Dublin at the Battle of Tara. After this victory, Máel Sechnaill forced Dublin to accept his rule.

Máel Sechnaill and Brian Boru (980–1022)

In Munster, the Dál gCais family grew powerful under Cennétig mac Lorcáin. His son, Mathgamain, was the first king not from the Eóganachta family to be called king of Munster. He was killed in 976 and succeeded by his brother, Brian, who became very famous.

Brian quickly became the strongest ruler in Munster. He defeated the Norse of Limerick in 977 and the Eóganachta in 978. He then tried to expand his power by raiding Osraige in 982 and 983. He even allied with the Norse of Waterford to attack Dublin.

Máel Sechnaill saw Brian as a threat. For the next two decades, they fought almost constantly, often in Leinster. Even though Brian never completely defeated Máel Sechnaill in battle, Brian's power grew. In 997, Máel Sechnaill had to accept Brian's authority over the south of Ireland. They formally divided Ireland into two halves, a northern part (Conn's half) and a southern part (Mug's half). For a few years, they worked together. In 999, Brian put down a revolt by Leinster and Dublin at the battle of Glen Mama. He only allowed Sigtrygg Silkbeard to rule Dublin again after Sigtrygg formally submitted to him.

In 1000, Brian turned against Máel Sechnaill. By 1002, he had forced Máel Sechnaill to submit and claimed kingship over all of Ireland. For the next ten years, he campaigned in the north to make the Ulaid and Northern Uí Néill accept his rule. Even with several rebellions, Brian had received submission from every major regional king in Ireland by 1011. This is why historians consider him the first true "king of Ireland." In 1005, he had his secretary write in the Book of Armagh that he was Imperator Scottorum (emperor of the Irish), suggesting he ruled both the Irish and the Norse in Ireland.

In 1012, Flaithbertach Ua Néill rebelled against Brian. The next year, Máel Mórda of Leinster and Sigtrygg of Dublin also rebelled. This led to the famous battle of Clontarf in 1014. Brian was killed, even though his army won the battle against Máel Mórda, Sigtrygg, and their allies. Forces from the Man and Sigurd Hlodvirsson, Earl of Orkney fought on the Dublin/Leinster side.

This battle created a popular myth that it was a decisive fight where the Irish defeated Viking invaders and gained freedom. However, historians like Donnchadh Ó Corráin have shown that this isn't entirely true. The Battle of Clontarf was mainly an internal struggle for power among Irish kings. The Norse were important allies, but they played a secondary role. The Norse had already become less powerful in Irish affairs long before Clontarf.

After Brian's death, Máel Sechnaill became High King again. In Munster, Brian's sons, Donnchad and Tadc, immediately started fighting for power. Although Donnchad eventually won, Brian's family wouldn't truly claim kingship over all Ireland again for a long time. In Leinster, the defeat at Clontarf weakened the Uí Dúnlainge family, allowing the Uí Cheinnselaig to become dominant. Despite the defeat, Sigtrygg remained ruler of Dublin until 1036.

High Kings with Opposition (1022 onwards)

After Máel Sechnaill's death, Donnchad mac Briain called himself 'King of Ireland' but couldn't get everyone to agree. No one else could either. Historians say that the period from 1022 to 1072 was seen by people at the time as a time without a clear high king.

The term rí Érenn co fressarba ("High kings with opposition") was used from the 12th century. This means that these kings faced a lot of challenges and didn't have full control over the whole island. They tried to be real kings of Ireland, but they faced strong resistance. After Brian Boru, the Uí Néill family's control over the high kingship was broken for good.

The Uí Néill family in the north suffered from internal fighting. This allowed the Ulaid, under Niall mac Eochada, to expand their influence. Niall and Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó of Leinster became allies. They effectively controlled the entire east coast of Ireland. This alliance helped Diarmait take direct control of Dublin in 1052. Unlike earlier kings, he didn't just loot the city; he took the title of "king of the foreigners" (ríge Gall) himself.

Changes in the Irish Church

There were big changes in the Irish church during the 12th century. These changes are often seen as a reaction to the church becoming too worldly, but they were also part of a continuous development. These reforms affected how the church worked and its relationship with political leaders.

Before the 11th century, the church in Ireland was mostly based in monasteries. Bishops lived at monasteries and there wasn't a clear system of dioceses (areas managed by a bishop). The first proper diocese in Ireland was established in Dublin during the reign of Sitric Silkbeard, when Dúnán became Bishop of Dublin.

Later, Dublin's bishops were consecrated (officially made bishops) by the Archbishop of Canterbury in England. Canterbury encouraged reforms in Ireland, like stopping the buying and selling of church positions.

Toirdelbach Ua Briain, an Irish king, seemed to support these reforms. He held a meeting of church leaders in Dublin in 1080. He might have seen working with Canterbury as a way to reduce the influence of Armagh, which was traditionally controlled by the Uí Néill family.

The first of four major church meetings (synods) for reform happened in Cashel in 1101, started by Muirchertach Ua Briain.

The second important synod was the Synod of Rathbreasail in 1111. This meeting changed the Irish church from being monastery-based to having a system of dioceses and parishes. It created two church provinces, with archbishops in Armagh and Cashel. Armagh was given the most important role. Each province had twelve dioceses. Dublin was not included at first because it was under Canterbury's authority, but a spot was left open for it.

Important church leaders like Gilla, Cellach, and St. Malachy pushed these reforms forward. Malachy helped establish the first Cistercian monastery in Ireland at Mellifont in 1142, and also the first Augustinian community. These new monasteries helped reform the church.

Malachy tried to get official approval from the Pope for the new church structure. His first attempt in 1139/40 was unsuccessful, but he was told to try again after getting agreement from all of Ireland. Before his second trip in 1148, Malachy held another meeting. The solution was to increase the number of archbishoprics from two to four, adding Tuam and Dublin alongside Cashel and Armagh. Malachy died on his way to see the Pope, but the message was delivered, and the Pope approved.

In 1152, Cardinal Paparo came to Ireland with the Pope's approval and held the Synod of Kells-Mellifont. This synod officially approved the new system of dioceses and archbishops in Ireland.

Norman Invasion

The Norman invasion of Ireland happened in two main steps. It began on May 1, 1169, when a group of Norman knights led by Raymond Fitzgerald landed near Bannow, County Wexford. They came because Dermot MacMurrough (Diarmait Mac Murchada), the king of Leinster who had been kicked out of his kingdom, asked for their help to get it back.

Then, on October 18, 1171, King Henry II of England landed a much larger army in Waterford. He wanted to make sure he had control over the Norman knights. He took Dublin and by 1172, the Irish kings and bishops had accepted him as their lord. This created the "Lordship of Ireland", which became part of his large Angevin Empire.

See also

- Early Scandinavian Dublin

- History of Ireland

- Scandinavian Scotland

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |