John Scotus Eriugena facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Scotus Eriugena

|

|

|---|---|

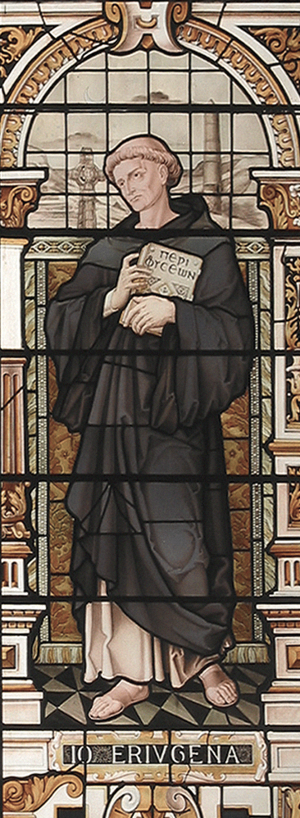

Stained glass window in the chapel of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. It shows John Scotus Eriugena holding his book De Divisione Naturae. Behind him are an Irish Round Tower and a Celtic cross. (1884)

|

|

| Born | c. 800 |

| Died | c. 877 (age c. 62) probably West Francia or Kingdom of Wessex

|

| Other names | Johannes Scottus Eriugena, Johannes Scotus Erigena, Johannes Scottigena |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism Augustinianism |

|

Main interests

|

Free Will, Intersubjectivity, Logic, Metaphysics, |

|

Notable ideas

|

Four divisions of nature |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

John Scotus Eriugena (born around 800 – died around 877) was an Irish philosopher, theologian, and poet from the Early Middle Ages. He was known for his unique ideas and his deep understanding of Neoplatonism, a type of philosophy based on the ideas of Plato.

Many people consider Eriugena to be one of the most important thinkers of his time. He was especially famous for knowing Greek, which was very rare in Western Europe back then. This skill allowed him to translate important Greek texts into Latin.

His most famous work is called De Divisione Naturae (which means "The Division of Nature"). In this book, he explored the idea that everything in reality, both what exists and what doesn't, is connected and comes from God. He tried to explain how the human mind and reality itself are linked through God's plan.

Contents

Who Was John Scotus Eriugena?

The name "Eriugena" means "Ireland-born," and "Scottus" was the Latin word for "Irish" during the Middle Ages. So, his full name means "John, the Irish-born Gael." This shows his strong connection to Ireland.

It's important not to confuse him with another famous philosopher, John Duns Scotus, who lived much later in Scotland.

His Life and Education

John Scotus Eriugena grew up and was educated in Ireland. Around 845, he moved to France after being invited by King Charles the Bald, a powerful ruler of the Carolingian dynasty.

In France, Eriugena became the head of the Palace School, a very important center of learning. He was known for his excellent knowledge of Greek, a skill he likely learned in Ireland. Under his leadership, the school became even more famous. He stayed in France for at least 30 years, and during this time, he wrote most of his important works.

There's a funny story about John and King Charles the Bald. One day, while they were eating, John made a rude noise. In Irish society, this might have been acceptable, but not in France. The King supposedly asked, "John, what separates an Irishman from a fool?" John quickly replied, "Oh, just a table!" The King found this very amusing.

The end of Eriugena's life is not entirely clear, but he likely died around 877 in France. We don't know for sure if he was a priest or a regular person, but it's thought he might have been a monk.

His Ideas on Theology

Eriugena's ideas were heavily influenced by earlier Christian thinkers like Origen, St. Augustine, and St. Maximus the Confessor. He also drew a lot from Neoplatonism, which shaped his view of how everything in the universe, both human and divine, is connected.

He believed that all reality is like a "graded ladder" coming down from God. He also saw a two-way movement in everything: things come from their source and then return to it. Even though his ideas were complex, Eriugena was a very religious Catholic. He deeply loved Jesus Christ and believed that understanding God was the most important thing.

On Divine Predestination

Eriugena was asked by Hincmar, an archbishop, to defend the idea of free will against a monk named Gottschalk. Gottschalk believed that God had already decided who would be saved and who would be condemned, a view called predestination.

Eriugena argued that philosophy and religion are basically the same. He said that because God is perfect and unchanging, God cannot predestine anyone to do evil or be condemned. He believed that evil and sin don't truly "exist" in the same way good does; they are more like an absence of good. Therefore, people are responsible for their own sins because of their free will.

His ideas were quite bold for the time. Some church councils later criticized his work, calling it "Irish porridge" and "an invention of the devil."

Translating Important Texts

Eriugena was a skilled translator. He made a new Latin translation of the writings of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a mysterious Christian writer whose works were very important. This translation was done at the request of King Charles the Bald.

His translations helped bring important Greek philosophical and theological ideas to Western Europe, where they had a big impact on Christian thought. He also translated works by St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Maximus Confessor.

His Masterpiece: De Divisione Naturae

Eriugena's most important book, De Divisione Naturae ("On the Division of Nature"), is divided into five parts. It's written as a conversation between a teacher and a student. In this book, Eriugena tries to explain the entire structure of reality.

He believed that reason is essential to understand religious truths. He famously said that "Authority is the source of knowledge, but the reason of mankind is the norm by which all authority is judged." This meant that human reason helps us understand and interpret what we learn from religious teachings.

Four Divisions of Nature

Eriugena described four main divisions of "nature":

- Creating and not created: This is God, the source of everything.

- Created and creating: These are the original ideas or forms (like blueprints) that exist in God's mind, which then create other things.

- Created and not creating: This is the physical world we live in, with all its objects and living things. They are created but don't create new things in the same way God or the original ideas do.

- Not creating and not created: This is God again, but seen as the final goal or end point of everything. All created things eventually return to God.

These divisions are not separate parts of God, but rather ways our minds try to understand God's relationship with the universe.

Understanding Non-Being

Eriugena also talked about five ways something can be "non-being" (not existing in the usual sense):

- God as unknowable: God is so great and excellent that our minds cannot fully understand Him. So, in a way, He "does not exist" in a way we can grasp.

- Higher things are hidden from lower: Things that are higher or more perfect in nature cannot be fully understood by things below them.

- Potential existence: Things that exist only as a possibility, like all future plants existing in a seed. They are not yet "actual."

- Physical world as temporary: The physical world, which changes and decays, is not "real being" in the same way that unchanging, spiritual things are.

- Sin as non-being: When humans sin, they move away from being like God. In this sense, sin is a "non-being" because it takes away from our true nature.

Knowing God Through Not Knowing

Eriugena believed that we can't truly know God as He is. We know that He exists, but not what He is. He can only be known through the things He has created. This is called theophany, meaning a "showing forth" of God's essence through creation.

He thought that God is beyond all words and thoughts. To say God is "superessential" (more than essential) is not to say what He is, but what He is not. This idea, called "negative theology," means that the best way to describe God is often by saying what He is not, because He is beyond all human concepts.

God's Nature

Eriugena saw God as being without beginning and completely self-sufficient. He believed that just as our minds express themselves in words and actions, God's essence reveals itself in the created universe. In this way, the universe is a "showing forth" of God's nature.

God and Creation: Not the Same

Some people thought Eriugena believed that God and creation were the same thing (a view called Pantheism). However, Eriugena himself denied this. He argued that creatures are manifestations of God, but they are not God Himself. It's like light coming from a lamp; the light shows the lamp, but it isn't the lamp itself.

Universal Return to God

Eriugena also had a unique idea about the end of the universe, called apocatastasis. He believed that eventually, everything in the cosmos would return to God. This doesn't mean things would be destroyed, but rather that they would be transformed and become more real in their connection to God. Even after the resurrection, he thought that while some would be blessed and others punished, this would happen within their own minds and consciences, rather than in a physical "hell."

His Lasting Influence

Eriugena's ideas were very bold and free-thinking for his time. He helped bring back philosophical thought in Western Europe after a long quiet period. He believed that philosophy and religion were deeply connected, and that reason was very important.

His work especially influenced mystics, people who seek a direct experience of God.

Bernard of Clairvaux

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a famous monk from the 12th century, was greatly influenced by Eriugena's ideas. Bernard used Eriugena's concepts of things coming from God and returning to God, blending them with the idea of God as Love. He believed that when a person loves God completely, they become fully absorbed in God, like air filled with light.

Hildegard of Bingen

St. Hildegard of Bingen, another important medieval figure, also showed Eriugena's influence in her writings and music. She shared his idea that humans, being made in God's image, can connect with the divine in unique ways. She also followed his view of the soul's journey back to God through the cosmos.

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa, a philosopher from the 15th century, was a very important interpreter of Eriugena's ideas. He took Eriugena's concept of God as the infinite One who contains all beings, and the idea of the universe as God creating Himself, and made them central to his own philosophical system.

Modern Philosophy

Some modern thinkers, like Leszek Kołakowski, have even suggested that Eriugena's way of thinking, especially in De Divisione Naturae, was an early version of the "dialectical" method used by later philosophers like Hegel and Marx. Eriugena's systematic approach earned him the nickname "the Hegel of the ninth century" among some scholars.

Legacy

John Scotus Eriugena is remembered as one of the most original and important thinkers of the Middle Ages. He even appeared on the Irish £5 note between 1976 and 1992!

His ideas continue to be studied today, showing how his bold thinking shaped philosophy and theology for centuries to come.

Works

Translations

- Johannis Scotti Eriugenae Periphyseon: (De Divisione Naturae), edited by I. P. Sheldon-Williams, (Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1968–1981) [Latin and English text of Books 1–3 of De Divisione Naturae]

- Periphyseon (The Division of Nature), translated by I. P. Sheldon-Williams and JJ O'Meara, (Montreal: Bellarmin, 1987)

- The Voice of the Eagle. The Heart of Celtic Christianity: John Scotus Eriugena's Homily on the Prologue to the Gospel of St. John, translated by Christopher Bamford, (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne; Edinburgh: Floris, 1990)

- Iohannis Scotti Eriugenae Periphyseon (De divisione naturae), edited by Édouard A. Jeauneau; translated into English by John J. O'Meara and I.P. Sheldon-Williams, (Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1995) [Latin and English text of Book 4 of De divisione naturae]

- Glossae divinae historiae: the Biblical glosses of John Scottus Eriugena, edited by John J. Contreni and Pádraig P. Ó Néill, (Firenze: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo, 1997)

- Treatise on divine predestination, translated by Mary Brennan, (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1998)

- A Thirteenth-Century Textbook of Mystical Theology at the University of Paris: the Mystical Theology of Dionysius the Areopagite in Eriugena's Latin Translation, translated by L. Michael Harrington, (Paris; Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2004)

- Paul Rorem, Eriugena's Commentary on the Dionysian Celestial Hierarchy, (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2005).

- Iohannis Scotti Erivgenae: Carmina, edited by Michael W. Herren, (Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1993)

See also

In Spanish: Juan Escoto Erígena para niños

In Spanish: Juan Escoto Erígena para niños

- Ignatian spirituality

- Mystical Theology

- Neoplatonism

- Neoplatonism and Christianity

- Pseudo-Dionysius

- Dialectical theology

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "John Scotus Eriugena". Catholic Encyclopedia 5. (1909). New York: Robert Appleton.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "John Scotus Eriugena". Catholic Encyclopedia 5. (1909). New York: Robert Appleton.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |