Alcuin facts for kids

Alcuin of York (born around 735 – died May 19, 804) was a very important scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria (which is now part of England). He was a student of Archbishop Ecgbert in York. Later, the powerful king Charlemagne invited him to his court. There, Alcuin became a leading scholar and teacher, playing a big role in what is known as the Carolingian Renaissance. This was a time when learning and culture became very important again in Europe.

Alcuin was known as "the most learned man anywhere to be found." He helped improve a clear writing style called Carolingian minuscule. This style used both capital and small letters, making books much easier to read. While he didn't invent it, he helped make sure it was copied and used widely. Alcuin wrote many books about religion and grammar, as well as poems. In 796, he became the head (abbot) of Marmoutier Abbey in Tours, France, where he stayed until he died.

Quick facts for kids

Alcuin of York

|

|

|---|---|

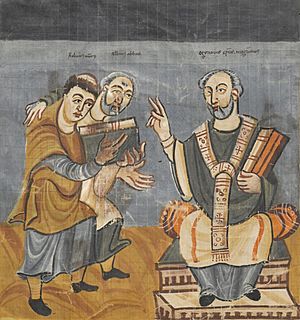

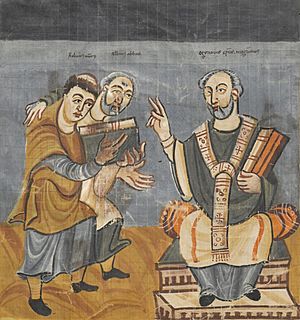

A Carolingian manuscript, c. 831. Rabanus Maurus (left), with Alcuin (middle), dedicating his work to Archbishop Odgar of Mainz (right)

|

|

| Born | c. 735 |

| Died | 19 May 804 (aged around 69) |

| Occupation | Deacon of the Catholic Church |

| Era | |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Scientific career | |

| Influences | Ecgbert of York |

Contents

Who Was Alcuin?

Early Life and Education

Alcuin was born in Northumbria, England, sometime in the 730s. We don't know much about his parents or family. He started his education at the cathedral church in York.

This was a special time for learning in York, thanks to Archbishop Ecgbert and King Eadberht. They wanted to improve the church and encourage learning, following the ideas of the famous scholar Venerable Bede. Alcuin learned a lot from Ecgbert and did very well.

The school in York was famous for teaching many subjects, including the liberal arts, literature, and science, as well as religious studies. Alcuin later used these ideas to help set up schools in France. He helped bring back important subjects like grammar, logic, and math.

Alcuin became a teacher in the 750s. He later became the head of the York school, which is now St Peter's School, York. Around the same time, he became a deacon in the church. He was never a priest, but he lived a life similar to a monk.

In 781, Alcuin traveled to Rome for King Elfwald. On his way back, he met Charlemagne in Italy. They had met once before, but this meeting was very important.

Working with Charlemagne

Alcuin was convinced to join Charlemagne's court, even though he was a bit unsure at first. Charlemagne had brought together many smart people from different places. This group included scholars like Peter of Pisa and Paulinus of Aquileia. Alcuin later wrote that he felt "the Lord was calling me to the service of King Charles."

In 782, Alcuin became the master of Charlemagne's Palace School in Aachen. This school was originally for the royal children to learn manners. But Charlemagne wanted it to teach the liberal arts and, most importantly, religion.

From 782 to 790, Alcuin taught Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, and other young people at the court. He brought his own assistants from York and completely changed the school. It became a place of serious study and learning.

Alcuin also advised Charlemagne. He disagreed with the king's idea of forcing people who weren't Christian to be baptized. Alcuin believed that faith should be a choice, not something forced. He said, "Faith is a free act of the will, not a forced act." His ideas seemed to work, as Charlemagne stopped punishing non-Christians with death in 797.

Charlemagne and his scholars became close friends. They even gave each other nicknames. Charlemagne was called 'David', like the biblical king. Alcuin was known as 'Albinus' or 'Flaccus'. Alcuin also gave nicknames to his students. He respected Charlemagne greatly, but also felt a bit of fear towards him.

Return to England and Back to France

In 790, Alcuin went back to England, but Charlemagne soon asked him to return. The king needed his help to fight against a religious idea called Adoptionism, which was spreading in Spain. Alcuin helped defend the traditional Christian beliefs at the Council of Frankfurt in 794.

While in England, Alcuin tried to advise King Æthelred, but he didn't succeed. So, Alcuin never went back to live in England permanently.

He was back at Charlemagne's court by 792. He wrote letters about the Viking attack on Lindisfarne in July 793. These letters and a poem he wrote are some of the only detailed accounts of this terrible event. He described it as: "Never before has such terror appeared in Britain. Behold the church of St Cuthbert, splattered with the blood of God's priests, robbed of its ornaments."

Later Life in Tours

| Saint Alcuin of York |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Deacon, Scholar, Abbot of Tours | |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion, Roman Catholic Church, as a blessed |

| Feast | 20 May |

In 796, when Alcuin was in his 60s, he wanted to retire from court life. Charlemagne made him the abbot of Marmoutier Abbey in Tours. He was still expected to offer advice if the king needed it.

At Tours, Alcuin encouraged the monks to copy manuscripts using the beautiful Carolingian minuscule script. This script is like an ancestor to the clear typefaces we use today.

Alcuin died on May 19, 804, about 10 years before Charlemagne. He was buried at St. Martin's Church. His tombstone read:

Dust, worms, and ashes now...

Alcuin my name, wisdom I always loved,

Pray, reader, for my soul.

Most of what we know about Alcuin comes from his many letters and poems. There is also a biography written about him in the 820s.

Alcuin's Impact and Legacy

Mathematician and Problem Solver

Alcuin is sometimes given credit for a collection of math and logic puzzles called Propositiones ad acuendos juvenes ("Problems to Sharpen Youths"). In a letter from 799, he mentioned sending "certain figures of arithmetic for the joy of cleverness" to Charlemagne. Some scholars believe this refers to these puzzles.

The book has about 53 math problems with solutions. They are not in any special order. Some famous problems include:

- Puzzles about crossing a river with specific rules, like the "problem of the wolf, goat, and cabbage."

- A problem about two adults and two children crossing a river, where the children weigh half as much as the adults.

- Alcuin's sequence is the answer to one of the problems in this book.

Influence on Learning

Alcuin made the abbey school in Tours an excellent place for learning, and many students came to study there. He had many books copied using beautiful writing, known as Carolingian minuscule.

He wrote many letters to his friends in England, to bishops, and especially to Charlemagne. Over 310 of these letters still exist. They are mostly about religious thoughts, but they also give us important information about life and learning during that time. They are a good source for understanding the "humanism" (focus on human values and learning) of the Carolingian era. Alcuin taught the monks at the abbey to be very religious and dedicated to their studies.

Alcuin is seen as the most important person in the Carolingian Renaissance. This period of renewed learning had three main parts:

- First, Italian scholars were most important.

- Second, Alcuin and other English scholars were in charge.

- Third, after 804, the influence of Theodulf the Visigoth became strongest.

Alcuin also created textbooks for his teaching, including books on grammar, rhetoric (the art of speaking and writing well), and dialectics (the art of logical discussion). These books were often written as dialogues, with Charlemagne and Alcuin as the characters. He also wrote several religious books and commentaries on the Bible. Some people believe Alcuin invented the first known question mark, though it looked different from the one we use today.

Alcuin helped bring the knowledge of Latin culture from Anglo-Saxon England to the Franks (people in what is now France). Many of his works still exist. He wrote some graceful letters and long poems, including a history in verse about the church in York. He also made one of the few comments we have from that time about Old English poetry. He wrote in a letter: "Let God's words be read at the episcopal dinner-table. It is right that a reader should be heard, not a harpist, patristic discourse, not pagan song. What has Ingeld to do with Christ?" This shows he preferred religious texts over old heroic poems.

Legacy

Alcuin is honored in the Church of England and the Episcopal Church on May 20.

Alcuin College, one of the colleges at the University of York, is named after him. In January 2020, Alcuin was the topic of the BBC Radio 4 radio show In Our Time.

Selected works

For a complete list of Alcuin's works, see Marie-Hélène Jullien and Françoise Perelman, eds., Clavis scriptorum latinorum medii aevi: Auctores Galliae 735–987. Tomus II: Alcuinus. Turnhout: Brepols, 1999.

Poetry

- Carmina, ed. Ernst Dümmler, MGH Poetae Latini aevi Carolini I. Berlin: Weidmann, 1881. 160–351.

- Godman, Peter, tr., Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1985. 118–149.

- Stella, Francesco, tr., comm., La poesia carolingia, Firenze: Le Lettere, 1995, pp. 94–96, 152–61, 266–67, 302–307, 364–371, 399–404, 455–457, 474–477, 503–507.

- Isbell, Harold, tr.. The Last Poets of Imperial Rome. Baltimore: Penguin, 1971.

- Poem on York, Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Euboricensis ecclesiae, ed. and tr. Peter Godman, The Bishops, Kings, and Saints of York. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982.

- De clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii, "On the destruction of the monastery of Lindisfarne" (Carmen 9, ed. Dümmler, pp. 229–235).

Letters

Of Alcuin's letters, over 310 have survived.

- Epistolae, ed. Ernst Dümmler, MGH Epistolae IV.2. Berlin: Weidmann, 1895. 1–493.

- Jaffé, Philipp, Ernst Dümmler, and W. Wattenbach, eds. Monumenta Alcuiniana. Berlin: Weidmann, 1873. 132–897.

- Chase, Colin, ed. Two Alcuin Letter-books. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1975.

- Allott, Stephen, tr. Alcuin of York, c. AD 732 to 804. His life and letters. York: William Sessions, 1974.

- Sturgeon, Thomas G., tr. The Letters of Alcuin: Part One, the Aachen Period (762–796). Harvard University PhD thesis, 1953.

Didactic works

- Ars grammatica. PL 101: 854–902.

- De orthographia, ed. H. Keil, Grammatici Latini VII, 1880. 295–312; ed. Sandra Bruni, Alcuino de orthographia. Florence: SISMEL, 1997.

- De dialectica. PL 101: 950–976.

- Disputatio regalis et nobilissimi juvenis Pippini cum Albino scholastico "Dialogue of Pepin, the Most Noble and Royal Youth, with the Teacher Albinus", ed. L. W. Daly and W. Suchier, Altercatio Hadriani Augusti et Epicteti Philosophi. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1939. 134–146; ed. Wilhelm Wilmanns, "Disputatio regalis et nobilissimi juvenis Pippini cum Albino scholastico". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum 14 (1869): 530–555, 562.

- Disputatio de rhetorica et de virtutibus sapientissimi regis Carli et Albini magistri, ed. and tr. Wilbur Samuel Howell, The Rhetoric of Alcuin and Charlemagne. New York: Russell and Russell, 1965 (1941); ed. C. Halm, Rhetorici Latini Minores. Leipzig: Teubner, 1863. 523–550.

- De virtutibus et vitiis (moral treatise dedicated to Count Wido of Brittany, 799–800). PL 101: 613–638 (transcript available online). A new critical edition is being prepared for the Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Medievalis.

- De animae ratione (ad Eulaliam virginem) (written for Gundrada, Charlemagne's cousin). PL 101: 639–650.

- De Cursu et Saltu Lunae ac Bissexto, astronomical treatise. PL 101: 979–1002.

- (?) Propositiones ad acuendos iuvenes, ed. Menso Folkerts, "Die alteste mathematische Aufgabensammlung in lateinischer Sprache: Die Alkuin zugeschriebenen Propositiones ad acuendos iuvenes; Überlieferung, Inhalt, Kritische Edition", in idem, Essays on Early Medieval Mathematics: The Latin Tradition. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003.

Theology

- Compendium in Canticum Canticorum: Alcuino, Commento al Cantico dei cantici – con i commenti anonimi Vox ecclesie e Vox antique ecclesie, ed. Rossana Guglielmetti, Firenze, SISMEL 2004

- Quaestiones in Genesim. PL 100: 515–566.

- De Fide Sanctae Trinitatis et de Incarnatione Christi; Quaestiones de Sancta Trinitate, ed. E. Knibbs and E. Ann Matter (Corpus Christianorum – Continuatio Mediaevalis 249: Brepols, 2012)

Hagiography

- Vita II Vedastis episcopi Atrebatensis. Revision of the earlier Vita Vedastis by Jonas of Bobbio. Patrologia Latina 101: 663–682.

- Vita Richarii confessoris Centulensis. Revision of an earlier anonymous life. MGH Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 4: 381–401.

- Vita Willibrordi archiepiscopi Traiectensis, ed. W. Levison, Passiones vitaeque sanctorum aevi Merovingici. MGH Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 7: 81–141.

See also

In Spanish: Alcuino de York para niños

In Spanish: Alcuino de York para niños

- Propositiones ad Acuendos Juvenes

- Carolingian art

- Carolingian Empire

- Category: Carolingian period

- Correctory

- Codex Vindobonensis 795