Carolingian art facts for kids

Carolingian art was a special kind of art made in the Frankish Empire between about 780 and 900 AD. This time is often called the Carolingian Renaissance, because it was a period of great rebirth in learning and art. It happened during the rule of Charlemagne and the kings who came right after him.

This art was mostly made for the royal court and important monasteries that the emperor supported. Art made outside these special places was usually not as good. Carolingian art was created in areas that are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy, and the Low Countries. It was also influenced by Insular art from Britain and Ireland, and some artists from the Byzantine Empire who lived in Carolingian lands.

For the first time in Northern Europe, artists tried to bring back and copy the art styles of ancient Rome and the Mediterranean. This led to a mix of classical (Roman) and Northern European ideas, creating a rich and grand style. It helped artists in the North learn how to draw people better. This period set the stage for later art styles like Romanesque art and Gothic art. The Carolingian era is part of what is sometimes called "Pre-Romanesque" art. After a short period of less art, the new Ottonian dynasty brought back imperial art around 950 AD, building on the Carolingian style.

Contents

What is Carolingian Art?

When Charlemagne built an empire as big as the Byzantine Empire and almost as large as the old Western Roman Empire, his court realized they needed an art style to match. They wanted art that could tell stories and show people clearly, which the older Germanic Migration period art could not do as well. Charlemagne wanted to be seen as a successor to the great rulers of the past. He aimed to connect his artistic achievements with the grand art of Early Christian and Byzantine cultures.

During Charlemagne's rule, there was a big debate in the Byzantine Empire called Byzantine Iconoclasm. This was about whether religious images should be allowed or not. Charlemagne supported the Western Church, which believed religious images were good. He even introduced the first large Christian religious sculptures in the West. This was a very important step for Western art.

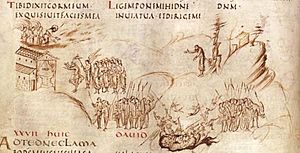

Many Carolingian illuminated manuscripts (decorated books) and small sculptures, mostly made of ivory, have survived. However, fewer examples of metalwork, mosaics, and frescoes (wall paintings) remain. Many of these manuscripts are copies or new versions of older Roman or Byzantine artworks that are now lost. The lively style of Insular art (from Britain and Ireland) also influenced Carolingian art. Sometimes, Carolingian artists used interlaced patterns and allowed decorations to spread around the text in a manuscript, similar to Insular art.

After the Carolingian rule ended around 900 AD, the quality of art declined for about 60-90 years. But by the late 10th century, with new religious movements and a renewed idea of empire, art production started again. New Pre-Romanesque styles appeared in Germany with Ottonian art, in England with late Anglo-Saxon art, and in Spain.

Illuminated Manuscripts

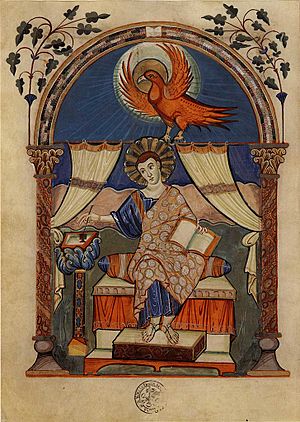

The most common surviving artworks from the Carolingian Renaissance are illuminated manuscripts. These are books, often Gospel books, that were beautifully decorated. They usually have a few full-page pictures, often showing evangelist portraits (pictures of the writers of the Gospels), and fancy canon tables. This style was inspired by the Insular art of Britain and Ireland.

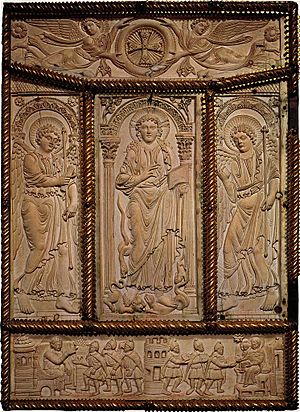

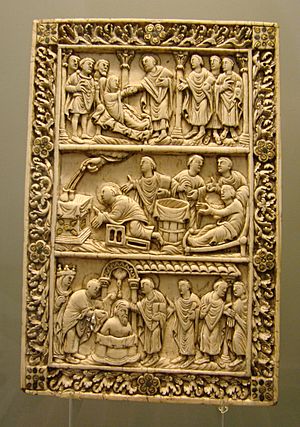

Stories and picture series are less common, but many exist, especially from the Old Testament, like the Genesis. Scenes from the New Testament are more often found on the ivory reliefs that covered the books. Carolingian artists adopted the large, decorated first letters from Insular art. They also developed the historiated initial, where small story scenes were included inside the letters, especially towards the end of the period, like in the Drogo Sacramentary.

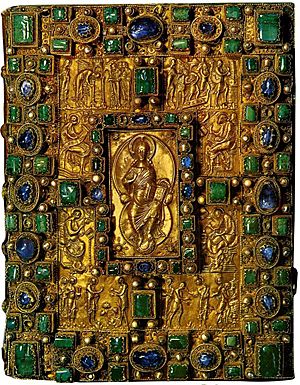

Fancy manuscripts had treasure bindings, which were rich covers made of gold, jewels, and carved ivory panels. Like Insular art, these were valuable objects kept in churches or treasuries. They were different from everyday books in libraries, which might only have a few decorated letters or pen drawings. Some of the grandest imperial manuscripts were even written on purple parchment. The Bern Physiologus is a rare example of a non-religious book with many painted pictures, perhaps made for a private library. The Utrecht Psalter is unique because it's a heavily illustrated version of the Psalms, done with pen and wash drawings, likely copied from a much older book.

Other religious books, like sacramentaries, were sometimes made as luxury manuscripts. However, no Carolingian Bible is as heavily decorated as some older Roman examples. Teaching books, such as those on theology, history, literature, and science from ancient writers, were copied but usually only had ink illustrations, if any.

Where were these books made?

Carolingian manuscripts were likely made by church members in a few workshops across the Carolingian Empire. Each workshop had its own style, based on the artists and influences of that place and time. We often know who ordered the books or which church they were given to, but rarely the names of the artists or exact dates. Scholars have studied the surviving manuscripts and assigned them to different workshops.

The earliest workshop was the Court School of Charlemagne (also called the Ada School). It produced manuscripts like the Godescalc Evangelistary (781–783) and the Lorsch Gospels (778–820). These books were very fancy and reminded people of 6th-century ivory carvings and mosaics from Ravenna, Italy. They started a revival of Roman classical art but still kept some older Germanic art styles, focusing on lines rather than showing depth or space.

In the early 9th century, Archbishop Ebbo of Rheims gathered artists near Rheims and changed Carolingian art. The Gospel book of Ebbo (816–835) was painted with quick, lively brush strokes, showing an energy not seen in classical art. Other books from the Rheims school include the Utrecht Psalter, which was very important, and the Bern Physiologus. The lively drawings of the Rheims school, especially the natural-looking figures in the Utrecht Psalter, influenced medieval art for centuries.

Another style developed at the monastery of St Martin of Tours. Here, large Bibles were illustrated based on older Roman Bible pictures. Three big Bibles were made in Tours, with the best one, the Vivian Bible, made around 845/846 for Charles the Bald. The Tours School ended when the Normans invaded in 853, but its style had already influenced other centers.

The diocese of Metz was another important center. Between 850 and 855, a sacramentary was made for Bishop Drogo, called the Drogo Sacramentary. Its illuminated "historiated" initials (decorated letters with small scenes inside) influenced art into the Romanesque period. They combined classical lettering with story scenes beautifully.

In the second half of the 9th century, the styles continued. Many richly decorated Bibles were made for Charles the Bald, mixing old Roman forms with the styles from Rheims and Tours. During this time, a Franco-Saxon style appeared in northern France. It combined the interlace patterns from Hiberno-Saxon art and lasted longer than other Carolingian styles.

Charles the Bald, like his grandfather Charlemagne, also set up a Court School. Its exact location is unknown, but several manuscripts are linked to it. The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram (870) is the last and most impressive. It combined elements from Tours and Rheims with the more formal style of Charlemagne's Court School.

After Charles the Bald died, support for making manuscripts decreased, marking the beginning of the end for this art period. However, some work continued. The Abbey of St. Gall created the Folchard Psalter (872) and the Golden Psalter (883). This style was unique but not as technically perfect as art from other regions.

Sculpture and Metalwork

Fancy Carolingian manuscripts were designed to have treasure bindings. These were ornate covers made of precious metal, set with jewels, and often had carved ivory panels in the center. Sometimes, these covers were added to the books later. Only a few complete covers have survived, but many ivory panels remain after the covers were broken apart for their valuable materials. The carvings often showed religious stories in vertical sections, inspired by older Roman and Byzantine art. Other panels had more formal images, like those on old Roman imperial art, such as the covers of the Lorsch Gospels, which changed a 6th-century Roman victory scene into a triumph of Christ and the Virgin Mary.

Important Carolingian gold artworks include the upper cover of the Lindau Gospels and the cover of the Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which dates to 870. These were likely made in the same workshop, linked to Holy Roman Emperor Charles II (the Bald), and often called his "Palace School." The exact location of this workshop is debated, but Saint-Denis Abbey near Paris is a strong possibility. The Arnulf Ciborium (a small model of a church canopy, not a container for hosts), now in Munich, is another major work from this group. All three have beautiful figures made from gold by pushing the metal out from the back (called repoussé). Another piece from this workshop is the frame for an antique serpentine dish in the Louvre museum.

Charlemagne also brought back large-scale bronze casting. He set up a foundry in Aachen that made bronze doors for his palace chapel, copying Roman designs. The chapel also had a life-size crucifix, now lost, with a gold figure of Christ. This was the first known artwork of its kind and became very important in medieval church art. It was probably a wooden figure covered in gold, similar to the Ottonian Golden Madonna of Essen.

One of the best examples of Carolingian gold work is the Golden Altar (824–859), a paliotto, in the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan. The altar's four sides are decorated with images made of gold and silver repoussé, framed by filigree (delicate metalwork), precious stones, and enamel.

The Lothair Crystal, from the mid-9th century, is one of about 20 large engraved rock crystal pieces that still exist. It shows many figures in several scenes telling the unusual story of Suzanna.

Mosaics and Frescoes

Historical records tell us that many wall paintings were in churches and palaces, but most have not survived. These paintings were mainly religious.

Mosaics in Charlemagne's palace chapel showed an enthroned Christ being worshipped by the Evangelist's symbols and the twenty-four elders from the Apocalypse. This mosaic is gone now. However, a restored mosaic remains in the apse of the oratory at Germigny-des-Prés (806 AD). It shows the Ark of the Covenant being worshipped by angels and was found in 1820 under a layer of plaster.

The villa connected to this oratory belonged to Bishop Theodulf of Orléans, a close friend of Charlemagne. The villa was destroyed later, but it had frescos (wall paintings) of the Seven liberal arts, the Four Seasons, and a Mappa Mundi (world map). We know from old writings about other frescoes in churches and palaces that are now almost completely lost. Charlemagne's palace in Aachen had a wall painting of the Liberal Arts and scenes from his war in Spain. The palace of Louis the Pious in Ingelheim had historical images from ancient times up to Charlemagne's era. Its church had typological scenes, showing connections between the Old and New Testaments.

Some small pieces of paintings have survived in places like Auxerre, Coblenz, Lorsch, Cologne, Fulda, Corvey, Trier, Müstair, Mals, Naturns, Cividale, Brescia, and Milan.

Spolia

Spolia is a Latin word meaning "spoils." In art, it refers to taking old artworks or parts of buildings and reusing them in new ways or places. We know that many marble pieces and columns were brought from Rome to the north during the Carolingian period.

Perhaps the most famous example of Carolingian spolia is the story of an equestrian (horseback) statue. In Rome, Charlemagne saw the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius at the Lateran Palace. This was the only surviving statue of a pre-Christian Roman Emperor because people mistakenly thought it was of Constantine, a Christian emperor. So, Charlemagne brought an equestrian statue from Ravenna to Aachen. People at the time believed it was of Theodoric the Great, and Charlemagne wanted it to match the "Constantine" statue in Rome.

Old carved gems were also reused in different settings, often without much thought for their original meaning.

See also

In Spanish: Arte carolingio para niños

In Spanish: Arte carolingio para niños

- Carolingian architecture

- Codex Vaticanus 3868

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |