Anglo-Saxon art facts for kids

Anglo-Saxon art is the art created in England during the Anglo-Saxon period. This time started in the 5th century when the Anglo-Saxons arrived from Europe. It ended in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Anglo-Saxon art was very important and influenced many parts of northern Europe.

There were two main times when this art was especially amazing. The first was in the 7th and 8th centuries. This period gave us beautiful metalwork and jewelry from places like Sutton Hoo. It also produced wonderful illuminated manuscripts (fancy handwritten books). The second great period was after 950. This was when English culture became strong again after the Viking invasions. By the time the Normans arrived, the art style was changing towards the Romanesque style. Important art centers were in Northumbria (north England) and Wessex and Kent (south England).

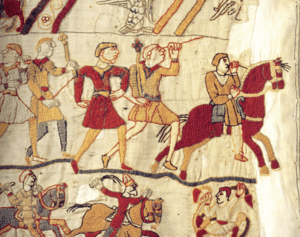

Most Anglo-Saxon art that still exists today is found in illuminated manuscripts. We also have examples of Anglo-Saxon architecture, beautiful ivory carvings, and some metal objects. Opus Anglicanum ("English work") was famous throughout Europe for being the best embroidery. However, only a few pieces from this time remain. The Bayeux Tapestry is a very large and famous example of this embroidery.

Metalwork was considered the most important type of art by the Anglo-Saxons. But sadly, very little of it survived. This is because the new Norman rulers took many treasures from churches and monasteries. The Vikings also plundered before them. Later, the English Reformation also led to the destruction of many artworks. Most metal pieces that survived were taken to other countries. Anglo-Saxon art loved bright colors and shiny materials. It takes imagination to see how these old, worn pieces once looked.

The Bayeux Tapestry is perhaps the most famous Anglo-Saxon artwork. A Norman leader asked English artists to create it. Anglo-Saxon artists also worked with fresco (wall painting), stone, ivory, and whalebone (like the Franks Casket). They also made metalwork (like the Fuller brooch), glass, and enamel. Many of these items have been found by archaeologists. Some were kept safe in churches on the European continent. This is because the Vikings, Normans, and the Reformation destroyed most art in England, except for books and buried treasures.

Contents

What is Anglo-Saxon Art Like?

The earliest Anglo-Saxon art we have is mostly metalwork. This includes jewelry and fittings for clothes and weapons. Before the Anglo-Saxons became Christian, these items were often buried with people. After they became Christian in the 7th century, their art changed. It mixed Germanic Anglo-Saxon styles with Celtic and Roman influences. This mix created the Hiberno-Saxon style, also known as Insular art.

This style is seen in illuminated manuscripts, carved stone, and ivory. It often used patterns from metalwork. The Kingdom of Northumbria in northern England was key to this style. Places like Lindisfarne and Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey were important art centers.

At the same time, missionaries from Rome brought a different, classical art style to Canterbury in the south. The Lindisfarne Gospels (early 8th century) show the Insular style. The Vespasian Psalter from Canterbury shows the classical style. These two styles blended over time. By the next century, a unique Anglo-Saxon style had fully developed.

However, the Viking invasions in the 9th century caused a lot of trouble. Fewer artworks survived from this time. Many monasteries in the north closed. After about 850, there were no major illuminated manuscripts until the 10th century. King Alfred (who ruled 871–899) stopped the Vikings. They settled in the Danelaw (part of England). Slowly, they became part of the unified Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

The last period of Anglo-Saxon art is called the Winchester School or style. It was made in many places in southern England. This style started around 900. The first major manuscripts appeared around the 930s. It combined art from the Holy Roman Empire with older English art. It often showed figures with nervous, agitated clothing. These were often line drawings, which were very common in medieval English art.

Illuminated Manuscripts

Early Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts are part of Insular art. This style mixes Mediterranean, Celtic, and Germanic influences. It began when Anglo-Saxons met Irish missionaries in Northumbria, especially at Lindisfarne and Iona. At the same time, missionaries from Rome brought continental manuscripts, like the Italian St. Augustine Gospels. For a long time, these two styles mixed in different ways in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts.

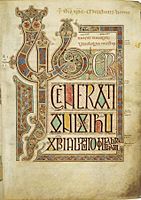

The Lindisfarne Gospels, made around 700–715, have incredibly complex and beautiful pages. But the portraits of the evangelists (authors of the Gospels) are simpler. They follow Italian styles but add interlace patterns. The portrait of St Matthew is similar to one in the Codex Amiatinus. However, the Codex Amiatinus has a more realistic style. This attempt to bring a pure Mediterranean style to England did not last.

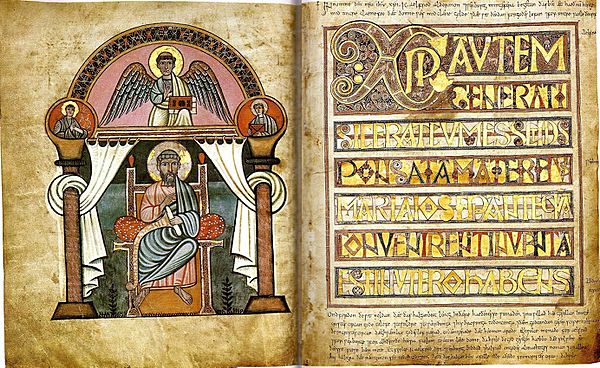

The Stockholm Codex Aureus (mid-8th century) shows a different mix. The evangelist portrait on the left is in an Italian style. It probably copied a lost original. But it adds interlace to the chair. The text page on the right is mostly Insular style. It has strong Celtic spirals and interlace. The same artist likely made both pages. This artist was skilled in both styles.

The 9th century has few surviving manuscripts made in England. But Anglo-Saxon art strongly influenced Carolingian art (art from Charlemagne's empire). English monks like Alcuin of York worked in important monasteries like Tours in France. These monasteries produced many manuscripts that showed English influences.

By the 10th century, Insular elements became just decorations in England. The first phase of the "Winchester style" began. Plant patterns, like leaves and grapes, started to appear. These patterns largely replaced interlace in Anglo-Saxon art. However, animals within these plant patterns remained common in England.

Many ambitious manuscript projects were never finished. The Old English Hexateuch has about 550 unfinished scenes. This gives us clues about how artists worked. The illustrations show Old Testament scenes in an Anglo-Saxon setting. They are valuable pictures of Anglo-Saxon life.

Manuscripts from the Winchester School only survive from about the 930s onwards. This was when English monasteries were being reformed and revived. King Æthelstan (who ruled 924/5-939) supported this. He promoted Dunstan (a skilled artist) to Archbishop of Canterbury. A manuscript given by Æthelstan around 937 shows a portrait of the king. He is presenting his book to a saint. This is the first real portrait of an English king. It was influenced by Carolingian art.

The Benedictional of St. Æthelwold is a masterpiece of the later Winchester style. It combined Insular, Carolingian, and Byzantine art styles. Anglo-Saxon art also included many lively pen drawings. The Utrecht Psalter, brought to Canterbury around 1000, was very influential. The Harley Psalter is a copy of it. Anglo-Saxon art was increasingly connected with the rest of Europe. Anglo-Saxon drawing greatly influenced northern France in the 11th century.

-

The Incipit to Matthew from the Book of Lindisfarne, an Insular masterpiece

-

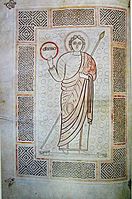

David from the Durham Cassiodorus, a rare non-liturgical illuminated manuscript from the early period.

-

The Baptism of Christ from the Benedictional of Saint Æthelwold, 970s.

-

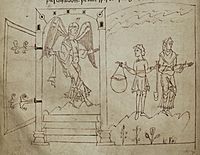

In this illustration from page 46 of the Caedmon manuscript, an angel is shown guarding the gates of paradise, after Adam and Eve have been expelled.

Metalwork

Early Anglo-Saxon metalwork used Germanic animal styles. But it slowly developed its own Anglo-Saxon look. Anglo-Saxon brooches are the most common surviving fine metal pieces from this early time. They were often buried with people. Round disk brooches were popular for important pieces. Decoration often included cloisonné (cellwork) using gold and garnet for high-status items.

The discovery of the ship-burial at Sutton Hoo (probably from the 620s) changed what we knew about Anglo-Saxon art. It showed amazing skill and quality for that time. The most famous finds are the helmet and the matching purse-lid and belt fittings. These items showed where many styles in Insular manuscripts came from.

By the 10th century, Anglo-Saxon metalwork was famous even in Italy. English goldsmiths worked on items for St Peter's in Rome. But almost no large pieces survived the Norman Conquest in 1066. We know large shrines, doors, and statues existed. But they were all lost.

We know the names of a few metalwork artists from this time. One was Spearhafoc, an 11th-century monastic artist. He was known for painting, gold-engraving, and goldsmithery. His art likely helped him rise quickly in the church. His work, though lost, tells us about Anglo-Saxon metalwork. Anglo-Saxon skill in engraving designs on gold was well-known. These engraved figures were similar to the many pen drawings in manuscripts.

Many monastic artists became important leaders. Spearhafoc's career was similar to Mannig, Abbot of Evesham (1044–58). And Saint Dunstan was a very successful Archbishop of Canterbury. These stories give us rare details about Anglo-Saxon goldsmiths.

In the last century of the period, large figures made of precious metal were recorded. These were likely thin sheets of metal over a wooden core. They were often life-sized crucifixes. Rich people and large monasteries spent a lot on art. Late Anglo-Saxon churches must have looked dazzling, like Eastern Orthodox churches. Anglo-Saxons loved expensive materials and the way light shone on precious metals. Vikings sometimes cut up decorated parts of looted items, like reliquaries. They took them home for their wives to wear as jewelry. Some of these pieces are now in Scandinavian museums.

While large works are lost, many small objects and fragments have been found. Most were buried. Metal-detecting and deep ploughing have found many new items. A few unburied items include the Fuller Brooch. Also, two works in Anglo-Saxon style were taken to Austria by missionaries: the Tassilo Chalice and the Rupertus Cross. In the 9th century, Anglo-Saxon styles influenced many smaller pieces of jewelry across northern Europe.

From England, the Alfred Jewel, with an enamel face, is very famous. It is one of many fine liturgical jewels. There are also high-quality disk brooches. The Pentney Hoard, found in 1978, had six beautiful silver brooches. They show small, twisted animals in plant patterns. These are in the "Trewhiddle style". The Staffordshire hoard, found in 2009, is a huge collection of 7th and 8th-century metalwork. It includes over 1,500 gold and military pieces. Many have high-quality gold and garnet inlays.

Early Anglo-Saxon coins, called sceats, show craftsmen trying to copy Roman styles. Later silver pennies had kings' heads in profile. These were more uniform and represented a stable currency. Some seax knives with decorations and inscriptions have survived. Sword fittings and other military pieces were also important jewelry.

-

Replica helmet from Sutton Hoo in Suffolk

-

The Alfred Jewel, probably (with a shaft affixed in its socket) a pointer for reading. The name AELFRED can be seen.

-

The Sutton-on-the-Forest Mount from North Yorkshire. An unusual strap mount in the form of an animal head

-

The Escrick ring of gold with a sapphire and glass inset

Stone Sculpture and Wall Painting

Besides Anglo-Saxon architecture, which survives in churches, we have large stone crosses. These are similar to the high crosses in Celtic areas of Britain. Most sculptures were probably once painted. This would have made the designs clearer. Today, they are very worn and weathered. It is often hard to know their exact age.

Wood sculpture was likely more common. But almost the only large piece left is St Cuthbert's coffin in Durham Cathedral. It was probably made in 698. It has many carved or incised images. Early crosses might have been made of wood. There are mentions of Anglo-Saxon pagan sculptures, probably in wood, but none remain.

Anglo-Saxon crosses have not survived as well as Irish ones. Many were destroyed after the English Reformation. Some crosses had large, high-quality figures. Examples include the Ruthwell Cross and Bewcastle Cross (both around 800). Vine-scroll and interlace patterns are seen on early Northumbrian crosses. Later crosses in the south often only used vine-scrolls. Some crosses have inscriptions in runes or Roman letters. The Ruthwell Cross famously has parts of the poem Dream of the Rood. These crosses might also have been decorated with metalwork and gems.

Anglo-Saxon crosses are usually tall and thin compared to Irish ones. They often have more space for patterns than figures. But there are exceptions, like the large Sandbach Crosses. These have figures covering most of their wide sides. The Gosforth Cross, from 930–950, is a rare complete example. Most crosses only have parts of their shafts left. Many crosses probably just fell over after centuries.

In the area of the Danelaw, like the Gosforth Cross, Christian images are mixed with pagan myths. For example, the Gosforth Cross shows Christian scenes and images from the Norse myth of Ragnarök. This theme could be used to teach Christian ideas.

Anglo-Scandinavians (Vikings who settled in England) eagerly adopted Anglo-Saxon sculpture. In Yorkshire alone, there are over 500 fragments from the 10th and 11th centuries. However, the quality was often not as good as earlier works. A unique Anglo-Scandinavian form is the hogback. This is a low grave-marker shaped like a long house with a pitched roof. It sometimes has bears at each end.

Many fragments of friezes and panels with figures and patterns have been found. They were often reused in rebuilt churches. The largest group of Anglo-Saxon sculpture is from Breedon-on-the-Hill. It includes lively decorative strips with human figures and panels with saints.

Literary sources tell us that wall paintings were common. But they were not considered as important as other art forms. Fragments of painted plaster have been found. A painted face on a reused stone at Winchester dates to before 903. This is an early example of the Winchester figure style. No complete wall or panel paintings have survived.

-

Bewcastle Cross - south and east faces

-

The Ruthwell Cross, Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland

-

The Gosforth Cross, Cumbria

-

Irton Cross, Cumbria

-

8th-century cross at Eyam in Derbyshire (section missing) with interlace; see here for face with vine-scrolls

-

The Hedda Stone in Peterborough Cathedral, a rare example of 8th-century Anglo-Saxon stone carving not from a cross.

-

Worn relief of an angel from St Mary's Church, Reculver in Kent

Ivory Carving

Small sculptures in metal, ivory carving, and bone carving were very important. Most Anglo-Saxon ivory came from marine animals, especially walruses. The amazing early Franks Casket is carved from whalebone. It has a unique mix of pagan, historical, and Christian scenes. It also has inscriptions in runes in Latin and Old English.

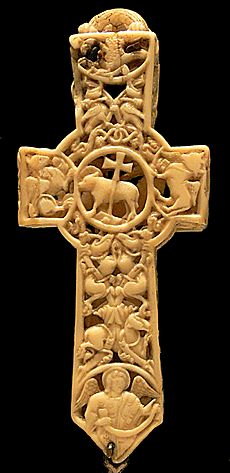

We have few Anglo-Saxon panels from book-covers. But we have many high-quality figures carved in high relief or fully in the round. In the last phase of Anglo-Saxon art, two styles appeared. One was heavier and formal, from Carolingian and Ottonian art. The other was the Winchester style, influenced by the Utrecht Psalter. A very late boxwood casket in Cleveland, Ohio, is carved with scenes from the Life of Christ. It is a rare example of late Anglo-Saxon fine wood carving.

-

Rear panel of the Franks Casket; Titus takes Jerusalem.

-

10th century Anglo-Saxon reliquary cross "corpus" on a German cross

Textile Art

Anglo-Saxon England was famous throughout Europe for its embroidery and "tapestry" (Opus anglicanum). But only a few pieces have survived. This is partly because Anglo-Saxons used precious metal threads. This made the work valuable for melting down.

The Bayeux Tapestry is embroidered with wool on linen. It tells the story of the Norman conquest of England. It is the most famous Anglo-Saxon artwork. Even though it was made after the Conquest, it was created in England and followed Anglo-Saxon traditions. Such tapestries decorated churches and wealthy homes. The Bayeux Tapestry is very large, about 0.5 by 68.38 meters (1.6 by 224.3 ft). Only the figures and decorations are embroidered. The background is left plain, which makes the subject clear. Women, both nuns and laywomen, created all kinds of textile arts. But artists in other media probably designed many of them.

The most valuable embroideries were made with silk and gold or silver thread. They sometimes had gems sewn in. These were used for church clothes, altar cloths, and in the homes of important people. Only a few pieces remain. Three pieces are in the coffin of St Cuthbert at Durham. They were probably placed there in the 930s. King Athelstan gave them. They were made in Winchester between 909 and 916. These works are "breathtakingly brilliant and high quality". They include figures of saints and early examples of the Winchester style.

Other Materials

Anglo-Saxon glass was usually simple. Vessels were always one color: clear, green, or brown. But some fancy claw beakers, decorated with large "claw" shapes, have survived. These are also found in northern Europe. Beads, common in early female burials, were more colorful. Some church window glass was also brightly colored. Many monasteries show signs of glass production.

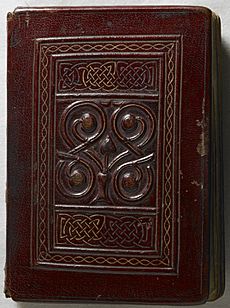

The unique decorated leather cover of the small Northumbrian St Cuthbert Gospel is the oldest Western bookbinding to survive unchanged. It dates to 698 or just before. It uses carved lines, some colors, and raised decoration. Larger, important manuscripts had metal treasure bindings. Many are mentioned, but none survive. There was likely much decorated leatherwork for bags, purses, and belts. But these were not often mentioned in records.

Aftermath

Not much art from the century after 1066 has survived. The Normans took over England and replaced the old Anglo-Saxon leaders. This led to a lot of destruction in churches. So, little important art was made. But when it was, the style often slowly changed from Anglo-Saxon to a full Romanesque style. Many artworks are hard to place exactly before or after the Norman Conquest.

The energy and love for complex patterns in Anglo-Saxon art influenced art on the European continent. It offered a different style from the heavy art of the Ottonian period. This way of thinking was important for both the Romanesque and Gothic styles. Anglo-Saxon inventions, like decorated initial letters, became even more important in later European art.

Anglo-Saxon art also created new ways to show certain ideas. These include the animal Hellmouth (a monster's mouth as the entrance to hell). Also, the ascending Christ shown only as feet disappearing at the top of an image. And Moses with horns, St John the Evangelist writing at the foot of the cross, and God the Father creating the world with a pair of compasses. All these ideas were later used across Europe. The earliest detailed picture of the Last Judgement in the West is on an Anglo-Saxon ivory. A late Anglo-Saxon Gospel book might show the earliest example of Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross in a Crucifixion.

See Also

- Medieval art

- Viking art

- Migration Period art

- List of illuminated Anglo-Saxon manuscripts

- Anglo-Saxon architecture

- Anglo-Saxon literature

- Anglo-Saxon glass

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |