Anglo-Saxon glass facts for kids

Anglo-Saxon glass is glass found in England from the Anglo-Saxon period (around 450 AD to 1066 AD). Archaeologists have discovered it at old settlements and burial sites. During this time, glass was used to make many things like drinking cups, beads, windows, and even parts of jewellery.

After the Romans left Britain in the 5th century AD, there was a big change in how much glass was used. Roman sites have lots of glass, but Anglo-Saxon sites from the 5th century onwards have very little. Most complete glass items, like cups and beads, come from early Anglo-Saxon graves. However, around the late 7th century, burial customs changed as Christianity spread. Christians were buried with fewer items, so less glass is found from this later period.

From the late 7th century, window glass became more common. This happened because new churches and monasteries were being built. Some old Anglo-Saxon writings also mention glass, mainly window glass used in these religious buildings. Anglo-Saxons also used glass in their jewellery, either as colourful enamel or as cut pieces set into metal.

Contents

Glass Vessels

Most of the complete glass cups and bowls we find come from early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries. This helps experts group similar glass vessels together into "typologies," which are like categories. Recent digs at Anglo-Saxon homes show that the glass used daily was similar to the glass buried in graves.

Anglo-Saxon glass vessels look very different from Roman ones. The ways glass was shaped also became simpler. Many Anglo-Saxon vessels couldn't stand on their own because they had rounded or pointed bottoms. This means people had to hold them until they finished their drink! We find fewer complete glass vessels from the 8th century onwards. This is linked to the spread of Christianity and the change in burial customs.

The first way to group Anglo-Saxon glass vessels was created by Dr. Donald B. Harden in 1956. Professor Vera Evison later updated this system, adding new types found since then.

Here are some common types of Anglo-Saxon glass vessels:

- Bowls: These were wide vessels, often with a flat bottom. They sometimes had decorations made by blowing glass into a mould.

- Cone Beakers: These were tall, narrow vessels that got wider at the top. They had pointed or curved bottoms.

- Stemmed and Bell Beakers: Bell beakers had a curved shape that narrowed to a point at the bottom. Stemmed beakers were similar but had a flat foot attached to the point.

- Claw Beakers: These started as delicate cups with decorative "dolphin" shapes. In the Anglo-Saxon period, they became thicker with simpler, claw-like decorations.

- Bottles: These were rare in Anglo-Saxon England compared to other parts of Europe like Germany and France.

- Palm Cups and Funnel Beakers: Palm cups were shaped like bowls but had a curved bottom. Funnel beakers were shaped like a funnel with a pointed bottom.

- Globular Beakers: These were the most common vessels in the 6th-7th centuries. They had narrow necks, wide round bodies, and pushed-in bottoms. They were often found in pairs.

- Pouch Bottles: These were unstable, round-bottomed vessels. Their shape and decoration were like globular beakers, but they were often taller.

- Bag Beakers: These were more cylindrical versions of the globular beaker, with rounded or pointed bottoms.

- Horns: These were drinking vessels shaped like animal horns.

- Inkwells: Fragments of inkwells from the 8th century show they were small, cylindrical vessels with a narrow opening at the top.

- Cylindrical Jars: A few pieces of cylindrical jars have also been found.

The glass used for Anglo-Saxon vessels was very similar to late Roman glass. It often had small amounts of iron, manganese, and titanium. The slightly higher iron content in early Anglo-Saxon glass made it look clear with a green-yellow tint. By the late 7th century, glass quality improved, and more colours were used. Sometimes, a second colour was added for decoration. Most Anglo-Saxon vessels were shaped by blowing glass freely, though some were made using moulds, often with vertical ridges. The edges of the vessels were usually smoothed by heat. Decorations were mostly made by adding thin lines or "trails" of glass, sometimes in a different colour.

Glass Beads

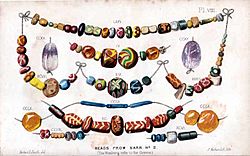

Most early Anglo-Saxon female graves contain beads, often found in large numbers around the neck and chest. Beads are sometimes found in male graves too, especially large ones with fancy weapons. Besides glass, Anglo-Saxons also made beads from amber, rock crystal, amethyst, bone, shells, coral, and metal. These beads were likely decorative, but they might also have had social or religious meanings.

Anglo-Saxon glass beads come in many different colours, sizes, shapes, and decorations. They also show a wide range of making techniques. Experts have studied where different types of beads were found and how they changed over time.

Some places where beads were made have been found in Europe, with leftover glass, beads, and glass rods. While many British archaeologists think most glass beads were imported, there's also evidence of bead making in early Christian Ireland, northern Britain, and later Anglo-Saxon sites. This suggests that at least three groups of beads were made in England.

Studies of Anglo-Saxon beads show that, like glass vessels, they were mostly made of soda-lime-silica glass with high amounts of manganese and iron oxide. The different colours came from variations in the glass's makeup. Lead-rich opaque (not see-through) glass was also common. This type of glass was easier to work with because it melted at a lower temperature and stayed soft longer, which helped prevent the bead from losing its shape. Beads could be made in several ways: by winding, drawing, piercing, folding, or a mix of these. Decorations were added by twisting coloured rods, creating mosaic patterns, putting metal between layers of clear glass, or simply adding drops or trails of different colours.

Window Glass

With the arrival of Christianity in the early 7th century and the building of churches, the amount of window glass increased. Window glass, some of it coloured, has been found at over 17 sites, mostly churches. Hundreds of window glass pieces have been discovered at places like Jarrow, Wearmouth, Brandon, Whithorn, and Winchester. This matches old stories, like the one by Bede, who wrote that Benedict Biscop brought glassmakers from France to make windows for the monastery at Wearmouth in 675 AD.

Most Anglo-Saxon window glass is thin, strong, and often has small bubbles. When it's clear, it has a pale bluish-green tint. Many church sites from the 7th century onwards also have brightly coloured glass. Studies of window glass from places like Beverley and Jarrow show it was mostly soda-lime-silica glass. However, its makeup was different from vessel glass, with less iron, manganese, and titanium. This suggests the raw materials came from a different place, possibly the Middle East. These studies also show how glassmakers started using potash (from wood ash) instead of soda as a main ingredient.

In ancient times, window glass could be made in three ways:

- Cylinder blown: A glass cylinder was blown, cut open, and flattened into a sheet. This was the most common method in Anglo-Saxon England.

- Crown manufacture: A blob of glass was spun until it flattened into a large disc.

- Cast: Molten glass was poured into a mould. Thick pieces of window glass with swirly surfaces found at Repton might have been made this way.

Jewellery Glass

In the 6th-7th centuries, much Anglo-Saxon jewellery used flat, cut red garnets set into gold. But sometimes, glass was also cut and used as gems. The glass colours were almost always blue and green. Red glass was sometimes used instead of garnet, for example, in some items from Sutton Hoo, like the purse-lid. Blue glass was used in the shoulder clasps from Sutton Hoo. The 7th-century Forsbrook Pendant also mixes garnet and blue glass. Anglo-Saxon enamel was also used in jewellery, where coloured glass was melted into separate small sections.

Chemical tests on this jewellery glass show it was soda-lime-silica glass, but with less iron and manganese oxide than the glass used for vessels. The glass in jewellery is very similar to old Roman coloured glass. This suggests that Anglo-Saxon craftworkers might have reused Roman opaque glass, possibly small Roman glass tiles called tesserae.

Glass Manufacture

Glass making is the process of creating raw glass from basic materials. Glass working is taking that raw glass (or recycled glass) and shaping it into new objects. These two activities could happen in the same place or in different locations.

Glass Making

Glass is made of four main parts:

- Former: This is silica, which came from sand during the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods.

- Alkali flux: This was soda or potash. In Roman and early Anglo-Saxon times, a mineral called natron (from Egypt) was used. Later, around 1000 AD, wood ash (which contains potash) became the main flux.

- Stabiliser: This was lime or magnesia. In Anglo-Saxon glass, lime was the main stabiliser. It might have been added on purpose or could have been naturally present in the sand used.

- Colourants/Opacifiers: These give glass its colour or make it opaque (not see-through). Some colours, like green or blue-green, came from impurities like iron in the sand. Other colours were made by adding small amounts of minerals or waste from metalworking. Elements like iron, manganese, cobalt, copper, tin, and antimony affected the glass's look. Lead was also important; it didn't create a colour itself but could change the shades of other colours. When added to opaque glass, lead helped colours spread evenly. Glass could be opaque due to strong colour, bubbles, or added agents like tin and antimony.

The main type of glass in the Anglo-Saxon period was soda-lime-silica glass, just like Roman glass. There's little evidence of glass making from raw materials in Anglo-Saxon Britain. It would have been very hard to transport natron from the Middle East to Britain. So, it's more likely that raw glass was made near the raw materials and then transported as solid lumps.

Another source of glass was cullet, which is recycled broken or crushed glass. Recycling was common in Roman times, and large amounts of broken glass found at Winchester and Hamwic suggest it was recycled in the Anglo-Saxon period too. By recycling glass, people could meet the demand for glass products without needing new raw glass. They might have also collected cullet from abandoned Roman sites.

In the late 7th-8th centuries, as many churches were built with large windows, the demand for glass grew. At the same time, political problems in Egypt caused a shortage of natron. This probably led glassmakers to try new fluxes, eventually leading to the use of wood ash (potash), which was easier to find.

Glass Working

Archaeological digs at Anglo-Saxon sites have found some signs of glass working, like crucibles (pots for melting glass), glass waste, and furnaces. However, no furnaces have been found directly with crucibles or glass waste. All the glass working furnaces found so far are at church sites like monasteries. This suggests that these religious centres supported most of the glass working in Anglo-Saxon Britain, probably to make windows for their buildings. Old writings suggest that glass workers travelled around the country, making glass when needed, possibly by reusing broken glass, rather than there being one main factory.

Even though we know how glass was made, it's still unclear how much glass working happened in Anglo-Saxon England and how widespread it was. The lack of clear evidence often leads people to think most glass was imported. But this seems unlikely, as there are few glass vessel making sites found elsewhere in Europe, and some Anglo-Saxon glass vessels are unique to England. This suggests some local production centres, perhaps in Kent. The small number of glass working sites found might be due to the fragmented nature of Anglo-Saxon archaeological records, and also because glass could be melted down and reused.

See Also

- Anglo-Saxon art

- Anglo-Saxons

- Forest glass

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |