Sutton Hoo facts for kids

The Sutton Hoo burial site

|

|

| Location | Woodbridge, Suffolk, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 52°5′23″N 1°20′20″E / 52.08972°N 1.33889°E |

| Type | Two early medieval cemeteries, one with ship burial |

| Site notes | |

| Ownership | National Trust |

Sutton Hoo is a famous archaeological site in Suffolk, England. It holds two ancient Anglo-Saxon cemeteries from the 6th and 7th centuries. Since 1938, archaeologists have been digging here. They found an amazing ship burial that was untouched. This burial contained many valuable Anglo-Saxon treasures.

The site is super important for understanding the history of the kingdom of East Anglia. It also helps us learn about the Anglo-Saxons. This was a time when not many written records were kept.

A self-taught archaeologist named Basil Brown first started digging. He worked for the landowner, Edith Pretty. When the site's importance became clear, national experts took over. They found incredible items in the ship burial. These included gold and gem jewelry, a fancy helmet, a shield, a sword, a musical instrument called a lyre, and silver plates.

The ship burial reminds many people of the epic poem Beowulf. This poem is partly set in Sweden, where similar archaeological finds have been made. Many experts believe that Rædwald, a king of the East Angles, was buried in the ship.

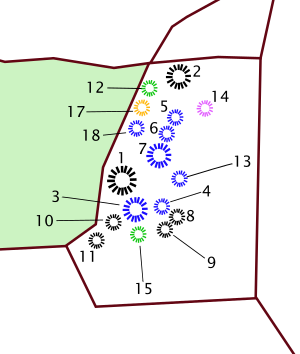

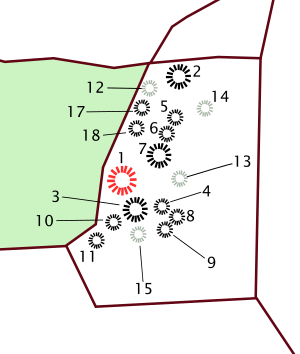

More burials were found in the 1960s and 1980s. Another burial ground was found in 2000. It was located on a hill near the first site. The cemeteries are close to the River Deben. They look like about 20 small hills or mounds.

Today, the site has a visitor center. It displays original artifacts and copies of the finds. You can also see a reconstruction of the ship burial chamber. The National Trust now cares for Sutton Hoo. Most of the original treasures are kept at the British Museum.

Contents

What Does "Sutton Hoo" Mean?

The name Sutton Hoo comes from Old English words. Sut and tun together mean "southern farm" or "settlement." Hoo means a hill shaped like a "heel spur." The name Hoi or Hou was recorded in the Domesday Book.

Where is Sutton Hoo Located?

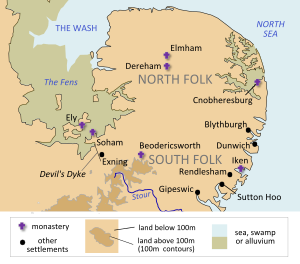

Sutton Hoo sits on a bank of the River Deben. You can still see large mounds there. They were once much taller and easier to spot. They overlook the river's upper part. Across the river is the town of Woodbridge. It is about 7 miles (11 km) from the North Sea.

This area was an important entry point into East Anglia. This was during the time after the Romans left Britain in the 5th century. Other ancient burial grounds are found nearby. These include sites at Rushmere, Little Bealings, and Tuddenham St Martin. A ship burial at Snape is the only other one in England like Sutton Hoo's.

The land between the Orwell and Deben rivers might have been an early center of royal power. This area was key to forming the East Anglian kingdom. Later, Ipswich grew as a trading hub.

Early Life at Sutton Hoo

Stone Age and Bronze Age Farmers

People lived at Sutton Hoo during the Neolithic period, around 3000 BC. Farmers cleared the forests to grow crops. They dug small pits and left earthenware pots inside.

During the Bronze Age, people started using metal tools. They built roundhouses with wooden frames and thatched roofs. One house had a central hearth where a special bead was found. These farmers used decorated pottery and grew barley, oats, and wheat. They also gathered hazelnuts. They dug ditches to divide their land. Over time, the soil became poor, and the settlement was left empty. Later, sheep or cattle were raised there.

Iron Age and Roman Times

In the Iron Age, iron became the main metal. Around 500 BC, people at Sutton Hoo started farming again. They divided the land into small fields. They might have grown grapes and large cabbages. This farming continued into the Romano-British period, from 43 AD to about 410 AD.

The arrival of the Romans did not change life much for the local Britons. A few Roman artifacts, like pottery pieces and a brooch, have been found. The land was heavily farmed, which made the soil worse. Eventually, the area was abandoned and became overgrown.

The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery

A Look at the Past

After the Romans left Britain, Germanic tribes like the Angles and Saxons settled in the southeast. East Anglia was an important area for these new settlers. The region's name comes from the Angles. Over time, the local people adopted the culture of these newcomers.

During this period, southern Britain was split into many small kingdoms. Several pagan cemeteries from the East Angles have been found. These include Spong Hill and Snape. Many graves contained grave goods like combs, jewelry, and weapons. Sometimes, sacrificed animals were also placed in the graves.

When the Sutton Hoo cemetery was used, the River Deben was a busy route for trade. Many small farms grew along the river. There was likely a larger center where important leaders lived. Archaeologists think this center might have been at Rendlesham or Sutton Hoo.

The Sutton Hoo grave field had about twenty burial mounds. It was used for important people who were buried alone with valuable items. This happened from about 575 to 625 AD. It was different from the Snape cemetery, which had both ship burials and graves with cremated ashes.

Burials in Mounds 17 and 14

Some of the earliest burials at Sutton Hoo were cremations. In 1938, two were dug up. Under Mound 3, a man's ashes were found with a horse. There was also a Frankish throwing-axe and items from the eastern Mediterranean. Mound 4 held the ashes of a man and a woman, with a horse and possibly a dog.

Other mounds (5, 6, 7) contained cremations in bronze bowls. These often included gaming-pieces, tools, and drinking vessels. Animal remains were also found, showing they were burned with the person.

Archaeologists also found graves where bodies were buried whole (inhumations). One small mound held a child with a buckle and a tiny spear. A man's grave had two belt buckles and a knife. A woman's grave contained a leather bag, a pin, and a chatelaine.

The most impressive burial without a chamber was in Mound 17. A young man was buried with his horse. The horse was likely sacrificed for the funeral. The man's oak coffin held his sword and sword-belt. Near his head were a firesteel and a pouch with garnets. Around the coffin were spears, a shield, a small cauldron, and a bronze bowl. A bridle with fancy gilt bronze plaques was also found. These items are now on display at Sutton Hoo.

Mound 14's grave was mostly destroyed by robbers. But it once held very high-quality items belonging to a woman. These included silver items like a chatelaine, a purse-lid, and buckles.

Mound 2: A Smaller Ship Burial

This important grave was damaged by looters. It was likely the source of many iron ship-rivets found in 1860. In 1938, more rivets were found, showing it was a small boat burial. Later digs showed a rectangular wooden chamber. A small ship was placed over this chamber before a large earth mound was built.

Scientists found traces of a body in the chamber floor. Items found included pieces of a blue glass cup, gilt-bronze discs, and a silver buckle. Some items were similar to those found in Mound 1. This shows a connection between the two burials.

Special Burials

The cemetery also contained remains of people who died in unusual ways. Sometimes, the bones did not survive. However, the flesh stained the sandy soil, showing the shapes of the bodies. Casts were made of some of these "sand bodies."

These burials were found in two main groups. One group was around Mound 5. It is thought that a gallows might have stood on Mound 5. This was a visible spot near a river crossing. These graves might have held people who were punished for crimes.

New Discoveries

In 2000, a team found more early Anglo-Saxon burials. This was during work for a new visitor center. Some of these graves had high-status objects. One find was part of a 6th-century bronze vessel from the eastern Mediterranean. It was decorated with a scene of warriors fighting lions. It also had a Greek inscription.

In another area, several burial mounds were found. They had been flattened over time. One burial had two pots and a well-preserved bronze hanging bowl. Another grave held a man with his spear and shield. The shield had fancy metal mounts showing a bird and a dragon.

The Amazing Ship Burial in Mound 1

The ship burial under Mound 1, found in 1939, was one of England's most magnificent archaeological discoveries. It was huge and complete. The items found were beautiful and showed connections to faraway places.

The Ship's Story

Almost none of the original wood survived. However, stains in the sand perfectly preserved the ship's shape. Even the iron rivets were in their original spots. The ship was about 89 feet (27 meters) long. It had tall ends and was about 14 feet (4.4 meters) wide in the middle.

The ship was built with nine planks on each side, fastened with rivets. Twenty-six wooden ribs made it strong. It had been a well-made seagoing vessel. The deck, benches, and mast were removed for the burial. There were spaces for forty oarsmen. A timber-walled chamber with a roof was built in the middle.

This heavy oak ship was pulled from the river up the hill. It was placed in a trench. Only the very tops of its ends rose above the ground. After the body and treasures were added, an oval mound was built over the ship. This mound was a powerful symbol to anyone using the river. This was likely the last time the Sutton Hoo cemetery was used for its original purpose.

Later, the roof of the burial chamber collapsed. This pressed the ship's contents into a layer of earth.

A full-size replica of the ship is being built. Work started in 2021, using oak planks and iron rivets. The goal is to learn how the ship actually sailed. A crew of at least 80 rowers will be trained.

Who Was Buried in the Ship?

Archaeologists found signs of a body on a platform or in a large coffin. An iron-bound wooden bucket, an iron lamp, and a bottle were nearby. The items suggest the head was at the west end of the structure.

The person buried in Mound 1 cannot be identified for sure. However, the items found were regalia, meaning they belonged to a king. Most guesses point to East Anglian kings. This is because the royal town of Rendlesham was nearby. Since 1940, Rædwald has been the most likely candidate.

Other kings like his sons Eorpwald or Sigeberht have also been suggested. Rædwald is favored because of the high quality of the treasures. Also, the huge effort needed for such a burial suggests a powerful ruler. The burial date, between 610 and 635 AD, fits Rædwald's reign.

Some experts still debate this. The museum at Sutton Hoo states the body is Rædwald. The British Museum says it's a "King of East Anglia." In 2025, a new idea suggested the body might be an important local soldier. This soldier might have fought for the Byzantine Empire.

A closer look at the sword hilt suggests the person was left-handed. The hilt's gold pieces are worn on the side opposite to what a right-handed person would cause. The sword was also placed on the right side of the body, which was unusual.

Because no body was found, some thought it was a cenotaph (a memorial without a body). Only a chemical stain showed where a body might have been. However, later soil tests in 1967 found phosphate traces. This supports the idea that a body had dissolved in the acidic soil. The cenotaph idea might fit with the change from pagan to Christian burials. The mound could have been a memorial for a Christian king.

Treasures from the Burial Chamber

The metal artworks found at Sutton Hoo are considered some of the best in Europe. They are key to studying art in Britain from the 6th to 9th centuries. The gold and garnet pieces show a mix of old techniques and designs. This "Insular style" combined Irish, Pictish, Anglo-Saxon, British, and Mediterranean art.

The burial chamber was full of rich items. These included jewelry, silver bowls, drinking vessels, clothing, and weapons. In 2016, researchers found lumps of tar from modern-day Syria. It's unclear what the tar was for, but it could have been for embalming or waterproofing.

The Helmet, Bowls, and Spoons

On the left side of the head was a "crested" and masked helmet. Its decoration is like helmets found in Sweden. The Sutton Hoo helmet is special because of its strong iron skull and full face mask. Helmets are very rare finds. This one was broken into many pieces when the chamber roof collapsed. These pieces were carefully put back together.

To the right of the head were ten silver bowls, stacked inside each other. They were likely made in the Eastern Empire around the 6th century. Under them were two silver spoons, possibly from the Byzantine Empire. They had the names of Apostles. One spoon said "PAULOS" (Paul) in Greek. The other was changed to say "SAULOS" (Saul). Some think these spoons were a baptismal gift.

Weapons and Armor

On the right side of the "body" were several spears. Nearby was a wand with a small wolf carving. Closer to the body was a sword with a gold and garnet handle. Its blade was still in its scabbard. The sword's belt was also found, with intricate gold and garnet decorations.

Purse, Shoulder-Clasps, and Buckle

The gold and garnet items found near the upper body are truly amazing. Their artistic and technical quality is outstanding.

The "great" gold buckle is made of three parts. It has a long, oval shape with detailed animal designs. The gold surfaces were punched for black niello details. The buckle is hollow and has a secret chamber, perhaps for a relic.

Each shoulder-clasp has two curved halves, joined by a pin. They have patterns of garnets and colorful glass inlays. The ends show interlocking wild boars. These clasps were used to hold together a stiff leather cuirass (body armor). No other Anglo-Saxon armor clasps like these are known.

The fancy purse-lid covered a lost leather pouch. It hung from the waist-belt. The lid has beautiful garnet plaques showing birds, wolves, and geometric patterns. These designs were inspired by Swedish-style helmets and shields. The craftsman was a master goldsmith.

The purse held thirty-seven gold coins, called tremisses. Each coin came from a different Frankish mint. There were also three blank coins and two small ingots. This collection might have been for paying ghostly oarsmen in the afterlife. Or it could have been a funeral gift or a sign of loyalty. These coins help date the burial to the early 7th century.

Other Items in the Chamber

Near the body's lower legs were drinking vessels. These included two drinking horns made from aurochs (an extinct type of wild cattle). There were also maplewood cups and a pile of folded textiles.

A large amount of material was found in two piles at the east end of the chamber. This included a rare coat of ring-mail (chainmail), two hanging bowls, leather shoes, and a feather-stuffed cushion. An iron hammer-axe was also found.

On top of these piles was a silver dish from Italy. It had a female head design. This dish held small wooden cups, antler combs, small knives, and a small silver bowl. A bone gaming-piece, possibly a "king piece," was also found. Above these was a silver ladle from the Mediterranean.

A very large round silver platter was placed over everything. It was made in the Eastern Empire around 500 AD. It had the stamps of Emperor Anastasius I (491–518). A piece of unburnt bone was on this plate. This collection of Mediterranean silver is unique for this time in Britain and Europe.

Walls of the Chamber

Along the west wall, a tall iron stand with a grid was found. Beside it was a large circular shield. It had a central boss decorated with garnets and animal patterns. The shield also had two large emblems: a predatory bird and a flying dragon. A small bell was nearby.

A long, square-shaped whetstone was also found. It had human faces carved on each side but showed no signs of being used as a tool. A bronze stag figurine was attached to its top. This might have been a symbol of power, like a Roman scepter.

In the southwest corner, a group of items was found. These included a bronze bowl from the eastern Mediterranean. Below it was a damaged six-stringed Anglo-Saxon lyre in a beaver-skin bag. On top was a large and fancy three-hooked hanging bowl. It had colorful enamel and glass designs, including a metal fish that could swivel.

At the east end, a wooden tub held a smaller bucket. Two small bronze cauldrons were also found. A large bronze cauldron with iron handles was hanging. Nearby was a long iron chain, almost 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) long. This chain was used to hang a cauldron from a hall's beams. These items were for everyday use.

Textiles

The burial chamber had many textiles. Fragments of twill were found, possibly from cloaks or blankets. There were also remains of cloaks with long-pile weaving. Some exotic colored hangings, possibly imported, were also present. These had stepped diamond patterns. Two other patterned textiles, near the head and foot of the body, looked like Scandinavian work.

Connections to Other Cultures

Similarities with Swedish Burials

The armor and burial style at Sutton Hoo are very similar to finds from the Vendel Period in Sweden. This suggests a Swedish cultural influence.

Excavations in Sweden in the late 1800s and early 1900s found 14 graves in Vendel and other princely burials at Valsgärde. Many of these were boat burials with swords, shields, and helmets. Ship burials from this period are mostly found in eastern Sweden and East Anglia. The famous Gokstad and Oseberg ship burials in Norway are from a later time.

The items found at Sutton Hoo, like drinking horns, a lyre, sword, and shield, are typical of important graves in England. The similar selection of goods shows that people of high status had similar possessions and funeral customs. Sutton Hoo is unique because of its exceptional quality and direct Scandinavian links.

One idea for these connections is that children of important leaders were often raised by friends or relatives in other lands. A future East Anglian king might have grown up in Sweden. There, he could have gotten high-quality objects and met skilled armor makers. Then he would return to East Anglia to rule.

Some historians believe the Wuffingas royal family might have come from Scandinavia. However, there are also big differences in the craftsmanship at Sutton Hoo. So, this connection is not fully proven.

Links to the Beowulf Poem

The Old English epic poem Beowulf is set in Denmark and Sweden in the early 6th century. It begins with the funeral of a great Danish king, Skjöldr, in a ship filled with treasure. The poem also describes other treasures and Beowulf's own mound burial.

Beowulf describes warrior life in a hall, with formal drinking, music from a lyre, and gifts for brave warriors. It also describes a helmet. All these things can be seen in the Sutton Hoo finds. The connections to eastern Sweden, seen in some Sutton Hoo artifacts, strengthen the link to the world of Beowulf.

Many scholars have explored how Sutton Hoo and Beowulf help us understand each other. The discovery of Sutton Hoo even led to more mentions of "silver" in Beowulf translations.

Some believe the Wuffing royal family was related to the Geatish house of Wulfing, mentioned in Beowulf. It's possible that the stories that became Beowulf were part of East Anglian royal traditions.

Digging Up the Past

Early Discoveries (Before 1938)

In medieval times, part of Mound 1 was dug away. In the 16th century, looters dug into what they thought was the center of Mound 1. But they missed the real burial, which was deep inside the ship. In 1860, people reported finding many iron ship rivets when a mound was opened.

Basil Brown and Charles Phillips: 1938–1939

In 1937, landowner Edith Pretty decided to have the mounds excavated. She hired Basil Brown, a self-taught archaeologist. In June 1938, Pretty suggested he start digging at Mound 1.

Brown decided to open three smaller mounds (2, 3, and 4) first. These had been robbed, so they only contained broken artifacts. In Mound 2, he found iron ship-rivets. This suggested a boat burial.

In May 1939, Brown began work on Mound 1. He was helped by Pretty's estate workers. On the third day, they found an iron rivet. Brown recognized it as a ship's rivet. Soon, many more were found. The huge size of the discovery became clear. After weeks of careful digging, they reached the burial chamber.

Charles Phillips from Cambridge University heard about the discovery. He was amazed by what he saw. Soon, Phillips and the British Museum took over the excavation of the burial chamber.

Pretty paid for two policemen to guard the site 24 hours a day. This was to keep reporters and treasure hunters away. After the finds were packed and sent to London, an inquest was held. It was decided that the treasure belonged to Pretty as the landowner. Pretty then generously gave the treasure to the nation. This way, everyone could share in the excitement of her discovery.

When World War II started in September 1939, the treasures were stored safely. Sutton Hoo was used as a training ground for military vehicles.

Rupert Bruce-Mitford: 1965–1971

After the war, a team led by Rupert Bruce-Mitford from the British Museum studied the artifacts. They helped reconstruct the scepter and helmet. They also worked to preserve the items for public display.

Bruce-Mitford believed there were still unanswered questions. So, a second archaeological dig was organized from 1965 to 1971. The ship impression was uncovered again. It was still mostly intact, so a plaster cast was made. The mound was later rebuilt to look as it did before 1939. The team also explored other areas and found evidence of prehistoric activity.

Martin Carver: 1983–1992

In 1982, Martin Carver from the University of York was chosen to lead a third major excavation. His goal was to learn about the "politics, social organization, and ideas" of Sutton Hoo. The project began in 1983.

Carver's team surveyed the site using new techniques. They found that the mounds were placed in relation to older prehistoric and Roman field patterns. Anglo-Saxon graves of people who died in unusual ways were also found. Mound 2 was re-explored and rebuilt. Mound 17, an untouched burial, was found to contain a young man, his weapons, and a separate grave for a horse. A large part of the grave field was left untouched for future archaeologists.

Recent Discoveries

In August 2024, a new excavation by the National Trust and the online show Time Team found more pieces of a 6th-century Byzantine bucket. By May 2025, the bucket was put back together. It is believed to have been used for cremation. The copper alloy bucket was decorated with a hunting scene. It was likely made decades before the Sutton Hoo ship.

Seeing the Treasures

Edith Pretty's gift of the ship-burial treasure was the largest ever given to the British Museum by a living person. The main items are now on permanent display at the British Museum. The Ipswich Museum shows original finds from Mounds 2, 3, and 4, and copies of the most important items from Mound 1.

In the 1990s, the Sutton Hoo site, including Sutton Hoo House, was given to the National Trust. At Sutton Hoo's visitor center, you can see the newly found hanging bowl and the Bromeswell Bucket. You can also see finds from the horse burial and a recreation of the burial chamber.

The visitor center, designed by van Heyningen and Haward Architects, opened in March 2002. It was opened by Nobel Prize winner Seamus Heaney, who had translated Beowulf.

Sutton Hoo in Stories and Games

- The Wuffings, a 1997 play, tells the story leading up to the Mound 1 burial.

- The Dig is a 2007 novel by John Preston. It reimagines the events of the 1939 excavation.

- The landscape of Sutton Hoo is also featured in the video game Assassin's Creed Valhalla, released in 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Sutton Hoo para niños

In Spanish: Sutton Hoo para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |