Anglo-Saxon lyre facts for kids

The Anglo-Saxon lyre was a stringed instrument played in Anglo-Saxon England and other Germanic parts of northern Europe. It's also known as the Germanic lyre or Viking lyre. The oldest lyre found in England dates back before 450 AD. The newest one found is from the 10th century.

People largely forgot about this instrument until the 19th century. That's when two lyres were found in Germany. A big discovery happened in 1939 at Sutton Hoo in England. When the Sutton Hoo lyre was correctly rebuilt in 1970, people realized it was "the typical early Germanic stringed instrument."

The Museum of London Archaeology says the lyre was the most important stringed instrument in the ancient world. Unlike lyres from ancient Greece or Rome, Germanic lyres were long and somewhat rectangular. They had a hollow soundbox that curved at the bottom. Two hollow arms connected at the top by a crossbar. Many wooden lyres have been found in warrior graves from the first thousand years AD, especially in England and Germany.

Contents

Excavated Lyres

Oberflacht (Germany)

The first Germanic lyre (called Oberflacht 37) was found in 1846. It was in a wooden burial chamber from the early 7th century in Oberflacht, Germany. Less than half of the lyre survived. It was broken into four pieces. Its soundbox and arms were made from oak. The soundboard was made of maple. At first, people thought it was part of a lute.

The second lyre (Oberflacht 84) was found in 1892 in the same cemetery. This lyre was almost complete. The soundbox was oak, and the soundboard was maple. Its arms bent slightly outwards at the top. The crossbar was attached with wooden pegs. This lyre had no sound-holes. It was moved to Berlin and kept in alcohol. Sadly, this lyre was destroyed during World War II.

Köln (Germany)

The Köln (or Cologne) lyre was found in 1939 during digs at the Basilica of St. Severin, Cologne. It was in a grave from the late 7th or early 8th century. Only the left half of the lyre survived. The soundbox was oak, covered with a maple board. This board was held on with copper alloy nails. The crossbar had six tuning pegs, but they fell apart. There was also a tail-piece made of iron. This lyre was also destroyed during bombing in June 1943.

Sutton Hoo (England)

The Sutton Hoo ship burial was dug up in 1939. It dates from the early 7th century. The lyre had been hanging in a beaver-skin bag. It fell and broke into pieces. Parts of it landed inside a Coptic bowl. What's left includes the crossbar, six tuning pegs, and two metal decorations shaped like bird heads. These joined the crossbar to the hollow arms.

The lyre was made from maple wood. The arms were hollowed out and covered with a maple soundboard. This was held on with bronze pins. There were five willow pegs and one alder wood peg. Beaver hair found on the lyre shows it was carried in a fur-lined bag.

When the Sutton Hoo lyre was found, it wasn't identified correctly. Rupert Bruce-Mitford thought it was a harp. In 1948, a strange reconstruction of the lyre as a rectangular harp was made. This was based on unclear pictures of harps from old Irish and English books. This harp was shown at the British Museum in 1949.

This idea changed in 1970. Rupert Bruce-Mitford and his daughter, Myrtle, correctly identified the instrument. They compared it to other lyre remains. The first Oberflacht lyre was in a museum. A broken English lyre, found in 1883 at Taplow Barrow, was finally recognized as a lyre too. The other German lyres were destroyed in the war, but their studies helped.

With the new Sutton Hoo lyre reconstruction, people realized something important. The musical instrument called a "hearpe" in Beowulf and other old writings was actually a lyre, not a harp. Later lyre finds in Trossingen (2001) and Prittlewell (2003) proved the Sutton Hoo reconstruction was right.

Trossingen (Germany)

The Trossingen lyre was found in 2001/2002. It was during digs at a cemetery in Trossingen, Germany. The lyre was in a narrow burial chamber with weapons and wooden furniture. It was found in wet conditions, so it was very well preserved.

The main body of the lyre was made from one piece of maple. The soundboard was also maple. It had a bridge made from willow and six tuning pegs. Four pegs were ash, and two were hazel. This lyre has amazing decorations. One side shows two groups of warriors. The rest of the space has animal-style patterns.

Prittlewell (England)

The Prittlewell royal Anglo-Saxon burial was found in 2003. It was one of the richest Anglo-Saxon graves ever. The wooden lyre had almost completely rotted away. Only a dark soil stain showed its shape. Small pieces of wood and metal fittings (iron, silver, and gilded copper-alloy) were still in their original spots.

The entire block of soil was carefully moved to a lab. There, scientists used X-rays, CT scans, and laser scans to study it. Tiny excavations showed the instrument was made of maple. Its tuning pegs were ash. The lyre had been broken in two at some point. It was fixed using iron, gilded copper-alloy, and silver repair pieces.

Lyre Finds to Date

At least 30 lyres of this type have been found by archaeologists. This includes one in Denmark, eleven in England, eight in Germany, two in the Netherlands, three in Norway, and four in Sweden. Most finds are either bridges or parts of the upper crossbar and its fittings. One find, from Sigtuna, Sweden, is a tuning key for adjusting the pegs.

| Date | Name | Country | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5th century | Abingdon | England | Curved bone crossbar piece with five holes |

| 580 AD | Trossingen | Germany | Almost complete lyre with detailed carvings |

| 590 AD | Prittlewell | England | Rotted wooden remains with metal fittings and wood pieces |

| 6th century | Oberflacht (84) | Germany | Almost complete lyre, lost in World War II |

| Late 6th / early 7th century | Schlotheim | Germany | Antler bridge |

| 6–7th century | Bergh Apton | England | Metal fittings and wooden arm pieces |

| 6–7th century | Eriswell 221 | England | Rotted wooden remains with copper-alloy fittings |

| 6–7th century | Eriswell 255 | England | Scattered wood and metal pieces in the shape of a lyre |

| 6–7th century | Eriswell 313 | England | Joined top part of a lyre |

| 7th century | Oberflacht (37) | Germany | Large pieces of the left side of a lyre |

| Early Anglo-Saxon | Morning Thorpe | England | Two wooden pieces with metal pins and plates |

| 610–635 AD | Sutton Hoo | England | Upper parts of the arms with two bronze bird plaques; a crossbar with six holes; and five pegs |

| 620–640 AD | Taplow | England | Metal bird ornaments and wooden pieces of the crossbar and joints |

| Anglo-Saxon | Snape | England | Wooden pieces from the arms and upper joints; copper alloy strip and pins |

| Late 7th / early 8th century | Köln | Germany | Roughly half of a lyre. Destroyed in World War II |

| 8th century | Ribe | Denmark | Wooden crossbar with six holes and four tuning pins |

| 8th century | Dorestad (140) | Netherlands | Amber bridge |

| 8th century | Dorestad (141) | Netherlands | Amber bridge |

| 8th century | Elisenhof I | Germany | Amber bridge piece |

| 8th century | Elisenhof II | Germany | Amber bridge |

| Viking age | Birka | Sweden | Antler bridge |

| Frankish | Concevreux | France | Bronze bridge with animal head decoration |

| 9th century | Broa | Sweden | Amber bridge |

| 10th century | York | England | Wooden bridge |

| 10–11th century | Hedeby | Germany | Arched wooden crossbar with six holes |

| 11th century | Gerete | Sweden | Bronze bridge |

| 1100 AD | Sigtuna | Sweden | Tuning key made from elk horn, carved with runes |

| Early 13th century | Trondheim | Norway | Wooden bridge |

| Early 13th century | Oslo I | Norway | Wooden bridge |

| Mid-13th century | Oslo II | Norway | Wooden bridge |

Etymology

Today, a lyre is an instrument where the strings are parallel to the soundboard, like a violin. A harp has strings that are perpendicular to the soundboard. This way of classifying them is new. In the past, people didn't make much difference between lyres and harps. In Old English, the lyre was called a "hearpe." In Old Norse, it was a "harpa."

An instrument called a "rote" or "rotta" appears in old books from the 8th to the 16th century. This name was sometimes used for box-shaped lyres. But some writings show that people might have used the name for harps too. The rote is probably related to the Irish word cruit and the Welsh bowed lyre called a crwth. In these old texts, "rote" clearly means a stringed instrument, but it's often unclear which one.

There isn't one modern name for the Anglo-Saxon lyre. Terms like "Germanic lyre" or "Viking lyre" are sometimes used. But these names have a regional bias. So, "Northern lyre" is sometimes used as a more neutral name.

Construction

Most lyre bodies found are made of maple, oak, or both. The bridges on the lyres were made from many different materials. These include bronze, amber, antler, horn, willow, and pine. The best wood for the pegs was ash, hazel, or willow. The lyres found range in length from about 53 cm (Köln) to 81 cm (Oberflacht 84). Half of the lyres found had six strings. A quarter had seven strings. The rest had five or eight strings, with only two having eight.

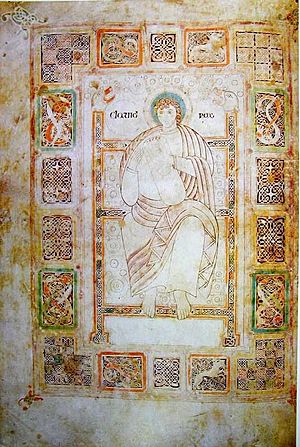

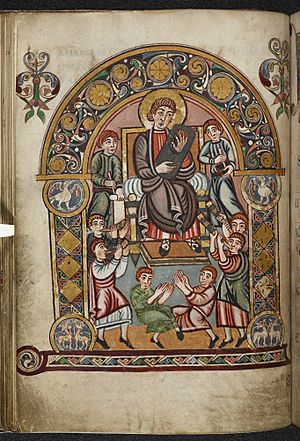

Anglo-Saxon Lyre in Ancient Images

Besides archaeological finds, researchers have found images of the lyre. The Vespasian Psalter, an early 8th-century Anglo-Saxon book, has the best image. It shows King David playing the lyre with his court musicians. This image was common in Christian art. Usually, David played a harp. But in some English versions, like the Vespasian Psalter, he has an Anglo-Saxon lyre. This image helps us understand how the lyre was played. It shows the left hand blocking strings, which is a "strum and block" technique. This method was also seen in ancient Greek lyre playing.

The Durham Cassiodorus is another book with an image of King David playing the Anglo-Saxon lyre. This book is from Northumbria, around the 8th century. The picture of David playing looks a bit awkward. It might have been drawn by an artist who had never actually seen the lyre being played.

The oldest image of a lyre comes from Gotland in Sweden. It's a rock carving from the 6th century.

Another image of the lyre being plucked is in the Utrecht Psalter. This is a 9th-century book of illustrations from the Netherlands.

Playing the Lyre

Many experts have studied how the lyre was played. Some are music historians who use their knowledge of old music. Others read old texts to find mentions of it.

The Vespasian Psalter and Durham Cassiodorus show how the lyre was held. They show it placed on one knee. One hand is held behind it to block or pluck strings. Playing this way for a long time would be hard. The left arm would get tired without a place to rest.

In five lyre finds, there's proof of a wrist strap. This strap would help hold the weight of the left arm. These finds include leather loops or plugs on the side of the lyre for a strap. Wear marks on the Trossingen lyre also show that the left hand gripped the arms when not playing.

Tuning

We don't know exactly how the lyre was tuned. The only old writing about lyres is from a monk named Hucbald. In his book, written around 880 AD, he describes how he thinks the Roman philosopher Boethius would have tuned his six-string lyre. Experts debate if Roman tuning methods apply to Anglo-Saxon lyres. Hucbald thought Boethius used the first six notes of the major scale.

Block and Strum Technique

The block and strum technique seems to have been very common for lyre playing. Pictures of it are found in ancient Egyptian art, on ancient Greek urns, and on the Anglo-Saxon lyre in the Vespasian Psalter. To use this technique, you strum the lyre. At the same time, your other hand mutes some strings. This way, only the strings that make a chord are heard. A lyre can make fewer chords than an instrument with frets. The number of strings also affects this. Another way to use strum and block is to tune one or more strings as drone strings. Then, you play the melody on the other strings, like a hurdy-gurdy.

Plucking

The Utrecht Psalter shows the Anglo-Saxon lyre being plucked. The musician is plucking two strings at once to make a chord. Plectrums were also used to play the lyre. The Anglo-Saxons had several words for plectrum, like "hearpenaegel." Some copper objects have been found that are the same size and shape as modern plastic plectrums. They might have been plectrums. However, no proven plectrums have survived. So, we can only guess what they were made of. Other possibilities include quills from bird feathers, which were used for medieval lutes. Medieval Ouds used plectrums made of animal horn and wood.

Anglo-Saxon Lyre in Literature

Among the Anglo-Saxons, music was seen as a gift from the Gods. It came from Woden, who was the God of knowledge, wisdom, and poetry. So, he gave the "magic" of music to people. Music was also seen as a power for good or evil. It could help heal minds, souls, or bodies. It could also harm enemies or summon spirits.

The lyre is mentioned 21 times in Anglo-Saxon poetry. Five of these mentions are in Beowulf. In literature, the lyre is often linked to storytelling. It was used during celebrations or in times of war.

|

þaér wæs gidd ond gléo: gomela Scilding |

there was song and glee: old Scylding |

| —Beowulf, lines 2105–10 |

Bede, who wrote about Cædmon (the "first" English poet), describes how the lyre was passed around at feasts. People could pick it up and sing songs as part of the fun. This was like other instruments, such as bagpipes, which were also passed around at feasts (mentioned in the Exeter Codex). The songs played on the lyre included Anglo-Saxon epic poems. It's likely that performances of Beowulf, the Wanderer, Deor, the Seafarer, and others, had the lyre playing in the background.

Origin and Relationship to Lyres Elsewhere

It's not completely clear how northern European lyres from the first thousand years are related to older lyres from the Mediterranean. Differences between Mediterranean and northern lyre cultures appeared much earlier than the Middle Ages. In the 4th century BC, a lyre was shown on a gold Scythian headband called the Sakhnivka Plate. This artwork, from a burial mound in modern Ukraine, shows a long, stretched-out lyre. It looks similar to later Germanic lyres.

Another similar find is a wooden instrument found in 1973. It was from a medieval settlement of the Dzhetyasar culture in southwest Kazahkstan. It dates to the 4th century AD. Recent studies show it is very similar to Germanic lyres. Another similar instrument is the traditional nares-jux, or Siberian lyre. It is played by the Khanty and Mansi people in Siberia.

In central Europe, lyres are shown on artifacts from the proto-Celtic Hallstatt culture around 700 BC. However, their shapes are very different from Germanic lyres. A later "lyre gauloise" is shown on a stone bust from the 2nd or 1st century BC. It was found in Brittany, France in 1988. It shows a figure wearing a torc playing a seven-string lyre. It was likely made of wood, but had a wider, rounder body, like the turtle-shell lyres of ancient Mediterranean cultures.

In 2010, a piece of wood was found in High Pasture Cave on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. It dates from the 4th century BC. Some non-experts think it's a lyre bridge, but this idea is highly debated. Even if it is a bridge, it only had two or three strings. So, it was likely a bowed lyre, similar to a Shetland Gue.

The six-string Germanic lyre tradition appears in archaeological records by the 2nd century AD. This was in a settlement at Habenhausen near Bremen, Germany. A wooden object found there in the 1980s turned out to be a lyre's crossbar. Its six holes show that the original instrument, only about 20 cm wide, had six strings.

See Also

- Kithara, a 7 string Greek lyre with a wooden soundbox

- Krar, a 5 or 6 string lyre from Ethiopia and Eritrea

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |