Taplow Barrow facts for kids

|

|

| Location | Taplow Court |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°31′52″N 0°41′42″W / 51.5311°N 0.6951°W |

| Type | Tumulus |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Medieval |

The Taplow Barrow is an ancient burial mound located in Taplow Court, a large estate in Buckinghamshire, England. It was built in the 600s, a time when this area was part of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom. The mound held the remains of an important person and their valuable belongings, known as grave goods. Most of these items are now kept at the British Museum.

Archaeologists often call this site the Taplow burial. It was created during a time when Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were starting to become Christian. This period saw the creation of very rich burials, like Taplow, which were much grander than earlier ones. Most of these special burials were not near churches. However, the Taplow Burial is one of the few exceptions, as it was likely placed next to an early church. The mound sits on a hill that was once an Iron Age hillfort, offering wide views of the surrounding area.

Inside the mound, archaeologists found the remains of one person. Experts believe this person was a local leader or chieftain. They were buried with many items, including military gear like a sword, three spears, and two shields. Other items found were drinking horns and glass cups. These expensive items show that the person was very important. Some items were made in Kent, suggesting the leader might have had connections with the Kingdom of Kent. Not much of the body survived, so scientists could not figure out the person's exact age or gender. However, the grave goods suggest the person was male.

The mound was first dug up in 1883 by three local history enthusiasts called antiquarians. At that time, it was the most impressive Anglo-Saxon burial ever found. It remained so until the discovery of the famous ship burial at Sutton Hoo in the 1930s. The items found at Taplow were given to the British Museum, where many are still on display today.

Contents

Understanding Anglo-Saxon Burials

In early medieval England, the 600s are sometimes called the "conversion period." This name helps tell it apart from the earlier "migration period" (the 400s and 500s).

People in early medieval England built many different types of burial monuments. One well-known type is the earthen mound, often called a "barrow." Many ancient barrows have been destroyed over time. However, a few still exist, even if they are smaller than they once were. Examples include barrows at Greenwich Park in London and the famous ones at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk.

Historians believe that the people who built these rich burial mounds in the late 500s and 600s were powerful leaders. They wanted to show off their status and importance. They also wanted to be remembered for a long time. These grand burials were a way to show their power and connect with an imagined past.

In early medieval England, it was very rare to find valuable items buried with people in churchyards. Usually, rich burials with many grave goods were separate from churchyard burials. Taplow is one of the few exceptions. It is a very rich burial found inside a churchyard. Other examples of grave goods found in churchyards from this time include sites in Eccles, Kent and St Paul-in-the-Bail, Lincoln.

The History of Taplow Mound

The name "Taplow" itself comes from the burial mound. It comes from an Old English phrase, Tæppas hláw, which means "Tæppa's mound." So, the unknown chief or nobleman buried there might have been named Tæppa.

When it was investigated in 1883, the mound was about 15 feet high in the middle. It was also about 240 feet around its base. It was described as being "somewhat bell-shaped." This shape might have been caused by later burials added around its eastern side.

The Taplow barrow is located inside an older Iron Age hillfort. It sits on the only hill in the area that offers long-distance views in many directions. This was probably a planned choice by its builders. Archaeologists think this important location was chosen to show power over the land. It also helped express a new identity for the buried person and their family. The mound was more than just a marker for the dead. It showed status and hinted at past and future importance. A similar high-up location was chosen for the ancient barrow at Asthall, Oxfordshire.

We do not know much about how the mound relates to other early medieval burials or the church itself. This is because the churchyard has not been fully excavated. The connection between the church and the mound raises important questions. It makes us wonder how Christianity spread and how leaders showed their power during that time.

Who Was Buried There?

Many archaeologists believe the person buried in the mound was male. After his excavation, Mr. Stevens thought the person was "a great chief." This chief would have ruled before Christianity came to Anglo-Saxon England. Since Buckinghamshire was part of Mercia during much of this period, Stevens thought the person might have been an important Mercian Angle.

Some experts have suggested the buried individual was a "Kentish prince." This idea comes from the high quality and origin of the items found with them. Many of the items were made in Kent. This suggests that the person might have had strong connections to the Kingdom of Kent. It also makes us think about Kent's influence over the Thames Valley during the 600s.

Amazing Grave Goods

The 1883 excavation found that the soil of the mound contained various old tools. These included flint tools, worked animal bones, and pieces of Roman pottery. This material was likely mixed into the soil when the mound was built. It was probably not placed there on purpose.

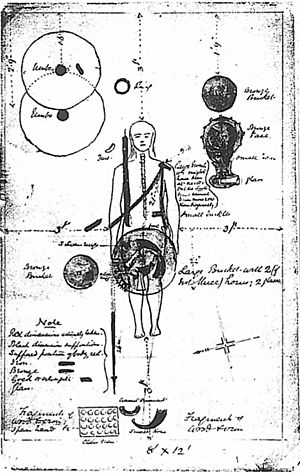

The actual burial was found beneath the base of the mound. The grave measured about twelve feet by eight feet and was aligned east to west. On its bottom was a layer of fine gravel. The only parts of the body that remained were a thigh bone and some small pieces of spine bones. There were no teeth, which usually survive well. Small pieces of fabric were also found. When examined under a microscope, they were thought to be wool.

The grave goods at Taplow were very impressive. However, they were not as rich or varied as those found in Sutton Hoo Mound 1. Still, historians compare Taplow with Sutton Hoo. They say both sites are "remarkable" for their many rich grave goods. They must have belonged to people who were more than just local leaders.

Items Found in the Grave

The items found in the grave are now at the British Museum. They include 19 vessels for feasting and drinking. There were also at least three sets of weapons, a lyre (a musical instrument), a gaming board, and rich textiles. This collection of items is similar to what a Germanic prince might have owned. Many of the objects seem to have come from the Kingdom of Kent. Several gold braids found might have been a symbol of royalty. The largest horns and the belt buckle seemed old when they were buried. This suggests they might have been family treasures from a "Kentish princely family."

The exact spot where each item was found in the grave was not precisely recorded. This was because the mound had collapsed into the burial chamber. However, the excavators made some guesses about where items were placed. They found evidence of rotten wood, suggesting a wooden plank might have been placed over the body.

Here are some of the items found:

- An iron sword, about 30 inches long and 2 1/2 inches wide. Traces of its scabbard (sheath) were seen. It was found on the left side of the body.

- Two iron shield bosses (the metal center part of a shield), each 5 inches wide. They were near the head of the grave, to the right of the body.

- An iron link and an iron ring.

- Three iron spearheads. One was a long type called an angon, 26 inches long. The other two were smaller. These were on the right side of the body.

- An iron knife or small seax (a type of sword).

- An iron cauldron or tub lined with bronze, two feet wide. It had been crushed. This was found crushed next to one of the buckets near the thighs.

- Two buckets made from wooden staves with bronze fittings. One was crushed with the cauldron. The other was on the left side of the body, near the head.

- A twelve-sided bronze bowl with two handles. This was also crushed. It was on the left side of the body.

- Four green glass drinking cups. These were broken. Three were found inside the tub, and the fourth was at the foot of the grave.

- Two large drinking horns with gilded silver mounts around their rims. The mounts were crushed. These were found inside the tub.

- Four smaller horns or cups with mounts. These were found in pieces. One was on the left side of the body, and the other at the foot of the burial.

- Small pieces of gold, spread over an area of about two yards. They were believed to be from some fabric.

- A gold buckle decorated with garnets, 4 inches long. Excavators thought it was placed about three feet east of the thigh bone.

- Two pairs of metal clasps, possibly gold. They might have been attached to a girdle (a belt). They were believed to be on the left side of the body.

- A crescent-shaped metal ornament, about 6 inches long. This was found at the foot of the grave.

- Several bone draughtsmen (pieces for a board game). These were found at the foot of the grave.

All these items are now at the British Museum, with several displayed in Room 41. The choice of grave goods shows an important lifestyle, both in this world and the next. The Taplow burial was considered the most impressive Anglo-Saxon burial until the discovery of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo Mound 1. Even in 2010, experts said Taplow was "second only to Sutton Hoo in wealth and display."

The Church and the Mound

The historian John Blair has suggested that there might not have been a church here before the Viking Age.

Taplow is not the only place where a church was built next to an important burial mound. Other examples are known from High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire and Ogbourne St Andrew in Wiltshire. Blair suggested that these churches might have been built in the 900s or early 1000s. This could have been done to make these old tombs Christian. People might have connected these tombs with local legends or important ancestors.

How the Mound Was Dug Up

In October 1883, an excavation of the barrow took place. It was led by Mr. Rutland, with help from Major Cooper King, Joseph Stevens, and Walter Money. The whole process took about three weeks.

Stevens noted that a large yew tree, likely hundreds of years old, was growing in the center of the barrow. To dig, a horizontal tunnel, six feet wide, was made from the south side of the mound. It was then expanded towards the center. The same was done from the north and then the west sides. During the digging, soil from under the yew tree collapsed into the trench, injuring Mr. Rutland. The work had to stop for several days. When they started again, the excavators found the body. But soon after, the yew tree fell into the trench, causing more delays. Only after the tree was removed could the grave goods be safely taken out. After the investigation, the mound was "restored to its former dimensions."

The grave goods were taken to Mr. Rutland's house for a short display. Then, the local clergyman, Reverend Charles Whately, offered them to the Trustees of the British Museum, who accepted. Stevens noted that the grave goods showed "a strongly marked Gothic element." He first thought the buried person might have been a Viking, but later concluded that an Anglo-Saxon origin was more likely.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |