Winchester Cathedral facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Winchester Cathedral |

|

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity and of Saint Peter and Saint Paul and of Saint Swithun in Winchester | |

View of the long nave, central tower and west end.

|

|

| 51°3′38″N 1°18′47″W / 51.06056°N 1.31306°W | |

| Location | Winchester, Hampshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk |

| History | |

| Dedication | |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 24 March 1950 |

| Style | Norman, Gothic |

| Years built | 1079–1532 |

| Groundbreaking | 1079 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 558 ft 1 in (170.1 m) |

| Nave width | 82 feet (25 m) (including aisles) |

| Nave height | 78 feet (24 m) |

| Floor area | 53,480 square feet (4,968 m2) |

| Tower height | 150 feet (46 m) |

| Bells | 14 + sharp 4th and flat 8th |

| Tenor bell weight | 35 long cwt 2 qr 6 lb (3,982 lb / 1,806 kg) |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Winchester (since c. 650) |

| Province | Canterbury |

Winchester Cathedral is a very old and important church in Winchester, England. Its full name is the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity and of Saint Peter and Saint Paul and of Saint Swithun. It is one of the largest cathedrals in Northern Europe. This huge building is the main church for the Diocese of Winchester and is led by a dean.

The cathedral you see today was built between 1079 and 1532. It is dedicated to several saints, especially Saint Swithun of Winchester. It has a very long and wide main hall, called a nave, built in the Perpendicular Gothic style. It also has older parts from the Norman period. At 558 feet (170 m) long, it is the longest medieval cathedral in the world. It is also the sixth-largest cathedral in the UK by area.

Many people visit the cathedral. In 2019, about 365,000 visitors came to see this amazing building.

Contents

A Look at Winchester Cathedral's Past

Early Churches in Winchester

Churches have been in Winchester since at least 164 AD. The first Christian church was built around 648 AD by King Cenwalh of Wessex. This small, cross-shaped building was just north of where the cathedral stands now. It was called the Old Minster. In 662, it became the main church for the new Diocese of Winchester. This area was very large, stretching from the English Channel to the River Thames.

Later, from 963 to 984, Bishop Æthethelwold made the Old Minster much bigger. It became the largest church in Europe for a short time. Another church, the New Minster, was also built nearby. It was started by Alfred the Great and finished by his son Edward the Elder in 901. These two churches stood side by side. The body of Saint Swithun, a famous Bishop of Winchester, was moved inside the Old Minster and placed in a special shrine.

The Norman Cathedral

After William the Conqueror took over England in 1066, he put his own bishops in charge. In 1070, William made his friend Walkelin the first Norman Bishop of Winchester. Nine years later, in 1079, Walkelin started building a huge new Norman cathedral. This new church was built on the site of the current cathedral, just south of the Old and New Minsters.

The new cathedral's east end was finished in 1093. Many tombs of Saxon kings were moved from the Old Minster into the new building. The very next day, the Old and New Minsters were torn down. You can still see the outline of the Old Minster today, north of the current main hall.

Work continued quickly on the side sections (transepts) and the central tower. These parts were finished by 1100, when King William Rufus was buried under the tower. Building the main hall (nave) was probably stopped in 1107 when the central tower fell down. But work restarted after the tower was rebuilt. It was finished before Bishop William Giffard died in 1129. Much of this early building work was very strong and still stands today, especially in the transepts. This Norman cathedral was enormous, over 500 feet (150 m) long, and it forms the core of the building you see now.

Gothic Style Changes

The first big change to Walkelin's cathedral happened in 1202. Bishop Godfrey de Luci began building a new section behind the altar, called a retrochoir, in the Early English Gothic style. This work continued after his death and led to the old Norman curved end (apse) being removed.

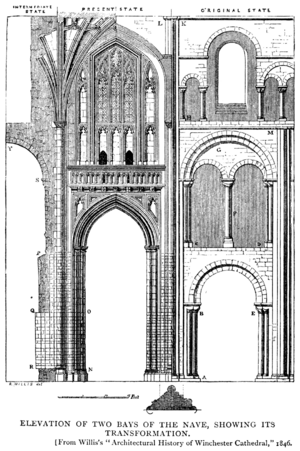

More changes and rebuilding took place in the mid-1300s. In 1346, Bishop Edington tore down the old Norman front and started building a new Perpendicular Gothic front. This new front had a huge west window, which is still there today. Edington also began to update the main hall (nave). However, most of this work was done by later bishops, especially William of Wykeham and his master builder, William Wynford. They changed the massive Norman nave into a tall, beautiful Perpendicular Gothic masterpiece. They did this by covering the old Norman stone with new stone and changing the arches. The wooden ceiling was replaced with a fancy stone ceiling. This work was finished around 1420.

From 1450 to 1528, under Bishops like William Waynflete and Richard Foxe, major rebuilding happened in the choir and retrochoir. They added more small chapels (chantry chapels) and replaced the Norman east end with a Perpendicular Gothic presbytery. The Lady Chapel was also made much longer. Unlike the nave, the presbytery ceiling was made of wood and painted to look like stone.

The Church of England Takes Over

In the 1500s, King Henry VIII took control of the Catholic Church in England and started the new Church of England. The monastery at Winchester, called the Priory of Saint Swithun, was closed down in 1539. The shrine of Saint Swithun was destroyed. The next year, a new group of church leaders was formed. Later, many of the old monastery buildings, like the cloister, were torn down.

Changes from the 1600s to 1800s

In the 1600s, important changes were made inside the cathedral. A new screen was put in front of the choir. A wooden fan-shaped ceiling was added under the central tower. In 1642, during the English Civil War, soldiers damaged much of the old stained glass and images. The huge Great West Window was almost completely destroyed. After the monarchy returned, the townspeople put the window back together like a mosaic, but it never looked the same.

In the 18th century, many people noticed that the cathedral and town were not well cared for. Major repairs began in the early 1800s. The famous writer Jane Austen was buried in the north nave aisle in 1817. Many visitors still come to see her grave today.

Saving the Cathedral in the 1900s

Around 1900, Winchester Cathedral was in serious danger of falling down. By 1905, huge cracks appeared in the walls, and stones were falling. The building was sinking into the soft ground because of problems with its foundations. An architect named Thomas G. Jackson and an engineer named Francis Fox discovered that the Normans had built the cathedral on a "floating raft" of beech trees. Some of these trees had rotted, causing the building to sink.

Fox and Jackson planned to dig trenches down to a solid layer of gravel and fill them with concrete and brick. But digging under the weak walls was risky. Water from the nearby River Itchen also flooded the trenches. Fox called in a brave diver named William Walker from London.

Walker had a very difficult job. He had to dive into the dark, cramped, flooded trenches in a heavy diving suit. The water was full of mud and old graves. For six years, from 1906 to 1911, Walker worked almost every day. He removed the soft ground and laid bags of cement to stop the water. He laid over 25,000 bags of concrete, 115,000 concrete blocks, and 900,000 bricks. His amazing work saved the cathedral from collapse.

In 1912, a special service was held to thank Jackson, Fox, and Walker. Walker was given a special award for his bravery. The total cost of the work was £113,000, which would be nearly £9 million today.

Winchester Cathedral in the 2000s

In February 2000, a three-year project to clean and repair the nave and west front was finished. In August 2006, a fire was almost started when a Chinese lantern landed on the roof. Luckily, it was put out quickly, preventing major damage.

In March 2011, a new small building was added to the cathedral. It was the first new extension since the 1500s. This building, called the Fleury building, provides toilets and storage.

Big Restoration Project (2012–2019)

In September 2012, a huge project began to raise £19 million for repairs and improvements. This project aimed to fix the old stained-glass windows, restore the wooden ceiling of the presbytery, replace the lead roof, update the sound system, and open a new exhibit about the Winchester Bible.

Workers found that the windows were badly corroded, and the lead roof above them was failing. This was damaging the 16th-century wooden ceiling. In July 2013, a grant of £10.5 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund allowed the work to start.

In 2014, a large scaffold was put up inside the presbytery so workers could reach the ceiling and windows. The south transept (one of the side sections) was emptied and prepared for a new exhibit called "Kings and Scribes." A massive scaffolding frame was built outside to cover the entire presbytery roof. In March 2015, a huge crane lifted this 27-tonne frame onto the roof. Over the next few weeks, 54 tonnes of old lead were removed from the roof and replaced. This part of the work was finished in May 2016.

In 2017, a very old statue was found on the south transept. It was replaced with a new one made of stronger stone. By February 2017, the fundraising goal had increased to £20.5 million. A pit was dug in the south transept floor for a new lift, making the exhibit accessible to everyone.

In June 2017, the lift shaft was installed. The 12th-century ceiling of the south transept aisle was carefully opened for this. By November, the last repaired stained-glass window was put back. The Great East Window was also restored. A new wooden floor was put in the triforium to protect the old uneven floor. The glass lift was installed, with its largest panels weighing 550 kilograms.

In January 2018, the internal scaffolding was slowly removed, allowing people to see the restored ceiling and windows. The Great Screen, a stone carving from the 1400s, was cleaned for the first time since 1890.

The entire project finished on May 21, 2019. The "Kings and Scribes" exhibit opened, all scaffolding was removed, and the south transept reopened after being closed for five years.

Cathedral Leadership Changes

In the summer of 2024, there were some changes in the cathedral's leadership. The director of music, Dr Andrew Lumsden, left his role. This led to concerns about how the cathedral's leaders were managing the music department. On June 18, 2024, Mark Byford, a senior non-executive member of the cathedral's Chapter, also resigned. The Bishop of Winchester, Philip Mounstephen, then asked for a review to understand what happened.

The review was completed in March 2025. It found that mistakes had been made by the leadership team. These included misunderstandings, poor judgment, and problems with how people were managed. The review also noted a "culture of secrecy." It recommended changes to the roles of Director of Music and Precentor.

The Dean, Catherine Ogle, stepped down immediately. She apologized on behalf of the Chapter to "everyone who has been hurt." On July 13, 2025, it was announced that Canon Andrew Trenier had also finished his time as Canon Precentor and Sacrist.

Cathedral Architecture

Winchester Cathedral is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals in Northern Europe. It is also the longest overall. The building shows how architectural styles changed over time, from the strong Norman work to the later Perpendicular Gothic style. The current building was started in 1079 and finished in 1532. It has a cross shape, with a long nave, transepts (side arms), a central tower, choir, presbytery, and Lady Chapel. Different types of stone were used, including local limestone, stone from Normandy, and Purbeck Marble. The cathedral is 558 feet (170 m) long, and its highest ceiling is 78 feet (24 m) high. The central tower is 150 feet (46 m) tall.

The north and south transepts are the oldest parts of the cathedral that haven't been changed much. They were built between 1079 and 1098. They are very large, about 209 feet (64 m) long across the middle. The walls are 75 feet (23 m) high. The transepts have three levels: an arcade (arches) at ground level, a triforium (middle gallery), and a clerestory (upper windows). Each transept has small chapels. Most of the windows in the transepts are Norman, but some Gothic windows were added later.

The central tower, which is 150 feet (46 m) high, was rebuilt in the Norman style after it fell in 1107. It was probably meant to be taller. A wooden fan-shaped ceiling was added in 1635 to allow bells to be installed above. Under the tower is the choir, separated from the nave by a large wooden screen from the 1870s. Behind the screen are the choir stalls, some of which date back to 1308.

The nave, the main hall, was built around 1100-1129. It was changed into the Perpendicular Gothic style between 1346 and 1420. Builders kept much of the original Norman structure but covered it with new stone. It is one of the widest Gothic naves in England and the longest of its kind in Europe. The nave has a beautiful stone ceiling with hundreds of decorative bosses (carved decorations). The nave, including its side aisles, is 82 feet (25 metres) wide.

The east end of the cathedral was built in two stages. The older part is the retrochoir, built between 1202 and 1220 in the Early English Gothic style. This section also has a stone ceiling and many decorative chapels for bishops. It was said to be a model for Salisbury Cathedral.

The newer part of the east end is the presbytery, built from 1458 to 1520 in the Perpendicular Gothic style. It has four sections with side aisles. Like the nave, it has two levels. However, the presbytery ceiling is made of wood and painted to look like stone. It has some of the most colorful roof bosses in the cathedral. The Lady Chapel was also made much longer during this time.

Underneath the cathedral is the crypt, a large Norman part of the building from the late 1000s. It has many sections and aisles and is vaulted in stone. The crypt often floods in winter because of the high water level. A famous statue by Antony Gormley of a life-sized man stands in the crypt.

-

William of Wykeham’s remodelled Gothic nave, the longest in Europe

-

Antony Gormley's Sound II in Winchester Cathedral's crypt whilst partially flooded.

-

Monument to Jane Austen

-

Rose cultivar 'Winchester Cathedral', Austin 1992

Stained Glass Windows

Much of Winchester's stained glass was lost during the time of Oliver Cromwell. The huge Great West Window was smashed. The glass from this window was put back together like a mosaic after the monarchy returned.

Most of the remaining stained glass is in the upper parts of the cathedral. The Great East Window, restored between 2012 and 2020, dates from the 1620s. It contains work by artists from Flanders. Much of the glass in the presbytery's upper windows dates from 1404 to 1426. The oldest stained-glass window in the cathedral is in the north transept, from 1330.

Cathedral Ceilings (Vaults)

Many parts of the cathedral have vaulted ceilings, some made of stone and others of wood. The oldest vaulted part is the 11th-century crypt, which has stone vaults. The nave and its aisles also have stone vaults. The aisles of the presbytery, the Lady Chapel, and the retrochoir are also vaulted in stone.

The ceiling under the central tower and in the presbytery is made of wood, painted to look like stone. Many of the small chapels (chantry chapels) have beautiful fan vaults. The highest ceiling in the cathedral is 78 feet (24 metres) above the ground. The transepts do not have vaults, but instead have wooden ceilings from the 1800s.

Special Items and Memorials

The cathedral holds many special items. These include a 12th-century font, the Morley Library, the Kings and Scribes exhibition, and the Winchester Bible. The font is a rare stone basin from around 1150, used for baptisms. It weighs 1.5 tonnes and has unique carvings showing stories of Saint Nicholas.

The Morley Library, located in the south transept, has a collection of rare books. These books were given to the cathedral by Bishop George Morley in the 1600s.

The Kings and Scribes exhibition is a new display that opened in 2019. It shows hundreds of old artifacts, like skulls, weapons, and building stones. It also uses modern technology. The famous Winchester Bible is part of this exhibit. It is considered the largest and best-preserved 12th-century Bible in England. The text was handwritten on 468 large sheets of calf-skin parchment. Some illustrations in the Bible used expensive lapis lazuli and gold leaf. The Bible is on display in a special climate-controlled room. Visitors can also read a digital version on large screens.

The cathedral also has many ancient chests containing the bones of kings and queens. These include Alfred the Great, King Canute, his wife Queen Emma, William Rufus, and King Egbert. Their remains were moved here after the Old Minster was torn down in 1093. During the English Civil War, these chests were disturbed, so the bones are now mixed up.

Chantry Chapels

Winchester Cathedral has many small, beautifully designed chapels called chantry chapels. These chapels are often dedicated to different Bishops of Winchester. Most of them are found in the retrochoir and also in the nave. Famous chantry chapels include those of William Wykeham, William Wayneflete, Richard Fox, and Henry Beaufort.

Music at the Cathedral

The Organ

The first organ at Winchester Cathedral was recorded in the 900s. It had 400 pipes and could be heard all over the city. This early organ needed two people to play it and 70 people to pump air into it! The current organ was first built in 1851 for the Great Exhibition in London. The cathedral's organist at the time, Samuel Wesley, was so impressed that he recommended buying it. It was installed in Winchester in 1854.

The organ has been changed and rebuilt several times since then. Today, it has more than 5,500 pipes and 79 stops. The main part of the organ is under the central tower.

Cathedral Choirs

Winchester Cathedral has several choirs. Its main choir is known around the world. It has 22 boy choristers, aged 8 to 13, and 12 adult singers called Lay Clerks. This choir sings six services a week during school terms. The boys go to The Pilgrim School, which is near the cathedral.

The Cathedral Girls' Choir was started in 1999. It has 20 girls, aged 12 to 17. They sing a weekly Sunday service with the Lay Clerks and join the boys for big festivals like Christmas and Easter.

The Cathedral Chamber Choir has 30 professional adult singers. They sing when the boy and girl choirs are on break. There is also a volunteer choir called the Cathedral Nave Choir, made up of 40 adults. They sing once a month.

Additionally, there are two youth choirs: the Junior Choir (ages 7-13, no audition needed) and the Youth Choir (over 14, requires an audition).

The Bells

Bells have been ringing from Winchester Cathedral since Saxon times. King Cnut gave two bells to the Old Minster in 1035, but those bells are no longer here. By the mid-1600s, seven bells were installed in the central tower.

Over the years, more bells were added and replaced. In 1891, the largest bell cracked and was recast. In 1921, two new bells were added, making it the first set of twelve bells in Hampshire. These new bells were dedicated to those who died in the First World War.

In 1936, all the bells were taken down and recast. They were meant for the coronation of King Edward VIII. However, by the time the bells were ready, Edward had given up his throne. So, the inscription on the largest bell had to be changed by hand to honor King George VI instead. The new bells were heavier and sounded much better.

In 1967, an extra bell from another church was added. This allowed for lighter ringing. By 1991, the tower itself needed repairs because the bell frame was moving too much. All 13 bells were lowered for the work. It was decided to add more bells, creating the world's first set of fourteen bells that can be rung in a special way called "diatonic change ringing." No major work has been done on the bells since 1992.

Cultural Connections

Winchester Cathedral attracts many tourists because of its link to Jane Austen. She died in Winchester in 1817 and is buried in the north aisle. Her tombstone doesn't mention her novels, but a later plaque describes her as "known to many by her writings."

The building was used as a film set for The Da Vinci Code in 2005, with the north transept used to represent the Vatican. After this, the cathedral held discussions to explain the differences between the book and reality.

Winchester Cathedral is one of the few cathedrals to have popular songs written about it. "Winchester Cathedral" was a hit song in 1966. The band Crosby, Stills & Nash also wrote a song called "Cathedral" in 1977. The band Clinic released an album titled Winchester Cathedral in 2004.

In 1992, a new type of white rose was named "Winchester Cathedral."

During the First World War, Bill Wilson, who helped start Alcoholics Anonymous, visited the cathedral and had an important spiritual experience there.

The cathedral is the starting point of the 34-mile-long St Swithun's Way, a walking path opened in 2002 to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II's Golden Jubilee.

The cathedral has been used as a filming location for The Crown, a popular TV series about the British monarchy. It has stood in for both Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral in the show.

Every November and December since 2006, the cathedral grounds host the Winchester Cathedral Christmas Market.

Visiting the Cathedral

Since March 2006, there has been an admission fee for visitors to enter the cathedral. However, visitors can ask for an annual pass for the same price as a single visit.

Cathedral Leadership

As of July 17, 2025, the leadership team includes:

- Dean: vacant (following the resignation of Catherine Ogle in March 2025)

- Interim Dean: Roland Riem (who was previously the Vice-Dean and Canon Chancellor)

- Canon Missioner: Dr Tess Kuin Lawton (since 2021)

- Canon Precentor and Sacrist: vacant (following the end of Andrew Trenier's time in July 2025)

- Non-executive members of Chapter: Professor Elizabeth Stuart, Alan Lovell, and Sarah Peppiatt

Burials and Memorials

Winchester Cathedral is the final resting place for many important people.

Burials Inside the Cathedral

- Saint Birinus – his remains were moved here.

- Walkelin, the first Norman Bishop of Winchester (1070–1098).

- Henry of Blois (or Henry of Winchester), Bishop of Winchester (1129–1171).

- Henry Beaufort (1375–1447), a Cardinal and Bishop of Winchester.

- Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler (died 1683).

- Jane Austen (died 1817).

Royal Bones in Mortuary Chests

Many early English kings and queens are buried here, but their bones are now mixed together in special chests. They were originally buried in the Old Minster and moved to the Norman cathedral in 1093.

- Cynegils, King of Wessex (611–643)

- Cenwalh, King of Wessex (643–672)

- Egbert of Wessex, King of Wessex (802–839)

- Ethelwulf, King of Wessex (839–856)

- Eadred, King of England (946–955)

- Eadwig, King of England (955–959)

- Cnut or Canute, King of England (1016–1035)

- Emma of Normandy, wife of King Cnut.

- William II 'Rufus', King of England (1087–1100).

Also, the chests contain bones believed to be from:

- Harthacnut, King of England (1040–1042)

- Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 1072)

One chest also mentions a king 'Edmund', though most records say King Edmund I and Edmund Ironside were buried elsewhere.

Kings Originally Buried at Winchester

- Edward the Elder, King of England (899–924) – later moved to Hyde Abbey.

- Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (875–899) – moved from Old Minster and later to Hyde Abbey.

See also

In Spanish: Catedral de Winchester para niños

In Spanish: Catedral de Winchester para niños

- Wedding of Mary I of England and Philip of Spain

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- English Gothic architecture

- Priory of Saint Swithun

- Romanesque architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |