Sutton Hoo helmet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sutton Hoo helmet |

|

|---|---|

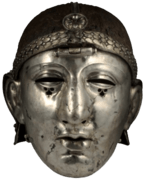

Latest reconstruction (built 1970–1971) of the Sutton Hoo helmet

|

|

| Material | Iron, bronze, tin, gold, silver, garnets |

| Weight | 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) estimated |

| Discovered | 1939 Sutton Hoo, Suffolk 52°05′21″N 01°20′17″E / 52.08917°N 1.33806°E |

| Discovered by | Charles Phillips |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Registration | 1939,1010.93 |

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a special Anglo-Saxon helmet. It was found in 1939 during an excavation of a ship burial site. This helmet was buried around 620–625 CE. Many people think it belonged to an Anglo-Saxon leader, possibly Rædwald of East Anglia, a king.

The helmet was not just for protection. Its fancy decorations might have made it like a crown. It was a strong piece of armor for fighting. It was also a beautiful and valuable metal artwork. This helmet is a famous object from a discovery called the "British Tutankhamen." It has become a symbol of the Early Middle Ages, of archaeology, and of England.

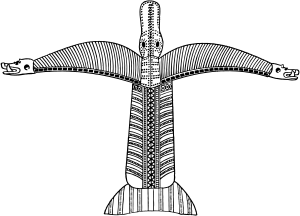

The front of the helmet looks like a face with eyebrows, a nose, and a mustache. This face joins with a dragon's head. It creates the image of a soaring dragon with its wings spread out. The helmet was found in hundreds of rusty pieces. It was first put back together in 1945–46. Its current look comes from a second reconstruction done in 1970–71.

The helmet and other items from the site belonged to Edith Pretty. She owned the land where they were found. She gave them to the British Museum. You can see the helmet there in Room 41.

What is the Sutton Hoo Helmet?

Discovering the Ancient Ship Burial

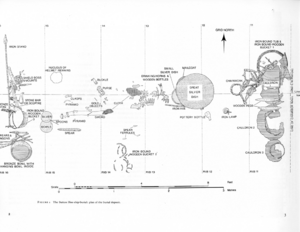

The helmet was buried with other royal items and symbols of power. This was part of a ship burial, probably from the early seventh century. The ship was pulled from a nearby river up a hill. Then it was lowered into a prepared trench.

Inside the ship, the helmet was wrapped in cloth. It was placed to the left of where the body's head would have been. A large oval mound was built over the ship. Much later, the roof of the burial chamber collapsed. This squashed the ship's contents into a layer of earth.

Experts believe the helmet broke when the burial chamber collapsed. Or it might have broken when another object fell on it. Because the helmet shattered, it was possible to rebuild it. If it had been crushed while the iron was still soft, it would have been squashed flat. This is what happened to helmets found in Vendel and Valsgärde.

Who Owned the Sutton Hoo Helmet?

People have tried to figure out who was buried in the ship since it was found. The most likely person is Rædwald of East Anglia. His kingdom, East Anglia, was probably based at Rendlesham. This town is about 4 miles upriver from Sutton Hoo.

The idea that Rædwald was the owner is not certain. But it is based on several clues. These include the burial date and the many rich, royal items found. Also, Rædwald was a king who had both Christian and pagan beliefs. The burial site shows signs of both.

King Rædwald's Life and Reign

We don't know much about King Rædwald of East Anglia. Most of what we know comes from a book written by the monk Bede in the eighth century. Rædwald was the son of Tytila and grandson of Wuffa. The Wuffingas royal family got its name from Wuffa.

Rædwald became king by at least 616. Bede writes that Rædwald helped Edwin of Northumbria by defeating Æthelfrith in a battle. Rædwald's wife convinced him to value friendship over money. After this battle, Rædwald's power was very strong. He was one of seven kings who ruled over all of England south of the River Humber.

Bede says Rædwald became a Christian during a trip to Kent. But his wife convinced him to change his mind when he returned. After that, he had a temple with two altars: one for pagan gods and one for Christian worship. Rædwald likely died sometime between 616 and 633.

Dating the Sutton Hoo Burial

To identify the person buried, we need to know the exact date of the burial. Thirty-seven gold coins from the Merovingian dynasty were found. These coins help us date the burial. Until 1960, people thought the coins were from 650–660 AD. This led them to believe other kings were buried there.

Later studies looked at the purity of the gold in the coins. Merovingian coins became less pure over time. This analysis suggests the latest coins were made between 613 and 635 AD. This means the burial likely happened closer to the beginning of that period. These dates fit with Rædwald's time, but they don't prove it was him.

Royal Symbols and Power

Many items found in the burial suggest a king was buried there. Some jewelry was more than just rich. The shoulder-clasps point to a special ceremonial outfit. The large gold buckle was very heavy. Its weight was equal to the price paid for a nobleman's death. This showed the wearer had great power.

The helmet itself shows both wealth and power. A small detail on the left eyebrow might connect the wearer to the one-eyed Germanic god Odin. Two other items, a "wand" and a whetstone, had no practical use. They were probably symbols of power. The whetstone, with its carved head, might have been a sceptre.

Mixing Christian and Pagan Beliefs

More evidence for Rædwald comes from items showing both Christian and pagan ideas. The burial is mostly pagan. It's a ship burial, an old pagan practice. This might have been a rejection of the new Christian faith from Francia.

However, three groups of items show Christian influences. These are two scabbard bosses, ten silver bowls, and two silver spoons. The bowls and scabbard bosses have crosses on them. The spoons are clearly Christian. They are engraved with a cross and the names ΠΑΥΛΟΣ (Paulos) and ΣΑΥΛΟΣ (Saulos). These names refer to Paul the Apostle. This might link to Rædwald's conversion to Christianity in Kent.

Other Possible Owners

Rædwald is the easiest name to connect to the Sutton Hoo burial. But the evidence isn't strong enough to be certain. People want to link the burial to a famous name more than the clues allow. The burial clearly shows wealth and power. But it doesn't have to be Rædwald, or even a king. It could have been a special offering.

The idea of Rædwald depends on how we understand wealth and power in the Middle Ages. The Sutton Hoo burial is amazing because no other similar burials from that time have been found. But this might just be because other graves were destroyed or looted. It's hard to tell the difference between the graves of chiefs, rulers, or kings. So, Rædwald remains a possible, but not certain, identification.

What Does the Sutton Hoo Helmet Look Like?

The Sutton Hoo helmet weighs about 2.5 kg. It was made of iron and covered with decorated sheets of bronze. Grooved strips divided the outside into panels. Each panel had one of five stamped designs. Two designs show people, and two show animal patterns. A fifth design is only known from seven small pieces. It might have been used to fix a damaged panel.

These five designs have been known since the first reconstruction in 1947. Over the next 30 years, people learned more about the designs. They found similar images from that time. This helped them figure out what the full panels looked like. It also helped them place the designs correctly on the helmet during the second reconstruction.

How the Helmet Was Built

The helmet's main part was an iron cap. From this cap hung a face mask, cheek guards, and a neck guard. The cap was shaped from a single piece of metal. Iron cheek guards hung on each side. They were deep enough to protect the whole side of the face. They curved inward to fit closely.

Two hinges on each side, possibly made of leather, held these pieces. This allowed them to close tightly with the face mask. A neck guard was attached to the back of the cap. It had two overlapping pieces. The inner piece allowed the neck guard to move more. Like the cheek guards, it was attached with leather hinges.

Finally, the face mask was attached to the cap with rivets. It had two eye openings. A third opening was for the hollow nose piece. This helped air get to the two small holes underneath, which were the only source of fresh air for the wearer.

Decorative sheets of bronze were placed over the iron. These sheets had five designs of figures or animals. They were made using a process called pressblech. This used pre-made dies, like stamps. Thin metal was pressed onto the dies to pick up the design. This allowed many identical designs to be made.

Grooved strips of a white metal alloy divided the designs into framed panels. These were held to the helmet with bronze rivets. The two strips along the crest were gilded (covered in gold). The helmet's edges were protected by U-shaped brass tubing. This also held the decorated panels in place.

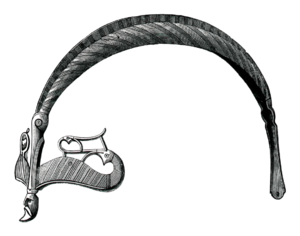

More decorations were added: a crest, eyebrows, a nose and mouth piece, and three dragon heads. A hollow iron crest ran across the top of the cap. It ended at the front and back. A gilded dragon head was riveted to each end of the crest.

A third bronze dragon head faced upwards on the front of the helmet. Its neck rested on the face mask. Its eyes were held to the cap by a large rivet. On each side of the neck were hollow bronze eyebrows. These had parallel silver wires inlaid in them. The ends of the eyebrows had gilded boar heads. Underneath the eyebrows, small bronze cells held square garnets.

The eyebrows were riveted to the cap. They were also attached to the nose and mouth piece. This piece was riveted to the cap in five places. Both sides of the nose had small round plates. These covered rivets. A silver wire strip ran along the nose ridge. The background was filled with niello or another metal inlay, leaving silver triangles.

Beneath these circles, the nose had chased patterns of plain and patterned strips. This pattern was repeated on the mustache. The curve of the lower lip repeated the circled pattern from the nose. Most of the nose and mouth piece was gilded. This was likely done using the fire-gilding method.

The helmet is not perfectly symmetrical. The two eyebrows are slightly different. The left eyebrow is about 5 millimeters shorter. It has fewer silver wires and garnets. The gilding on the right eyebrow is reddish, while the left is yellowish. Also, the individual bronze cells holding the garnets on the right eyebrow have small pieces of gold foil underneath. The left eyebrow and one dragon eye do not. This gold backing made the garnets shine more. The missing backing on the left side might suggest a link to the one-eyed god Odin.

Dragon Designs on the Helmet

The helmet has three dragon heads. Two gilded bronze dragon heads are on each end of the iron crest. The third dragon head is at the front, between the eyebrows. The eyebrows, nose, and mustache complete the image of a dragon in flight.

The dragon flies upwards. Its garnet-lined wings might look like fiery trails. This dramatic part of the helmet shows the dragon baring its teeth at another snake-like dragon flying down the crest. Most of the helmet's jewels are on these dragon parts.

Garnets set into the heads give the dragons red eyes. The eyebrows also have square garnets on their undersides. These continue outwards to gilded boar heads. So, the eyebrows might also look like boar bodies. The slight differences in the eyebrows might hint at the one-eyed god Odin. In dim light, only one eye might reflect light, making the helmet appear one-eyed.

More gold covers the eyebrows, nose and mouth piece, and dragon heads. It also covers the two grooved strips next to the crest. The crest and eyebrows also have silver wires. The helmet would have looked like a shiny silver object. It had a gold framework, a large silver crest, and gilded decorations, garnets, and niello. It was a magnificent piece of art.

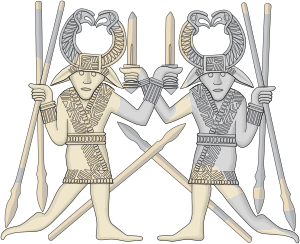

Design 1: Dancing Warriors

This design shows dancing warriors. It is found four times on the helmet. It appears on the two panels above the eyebrows. Another piece is on the right cheek guard. The helmet is symmetrical, so it was likely on the other side too.

Design 1 shows two men in ceremonial clothes. They might be doing a spear or sword dance. This dance was linked to the war-god Odin. Their outer hands hold two spears. Their crossed hands hold swords. The image suggests complex, rhythmic dance steps.

Similar dance scenes are common in old Scandinavian art. This shows that ritual dances were well-known. Sword dances were recorded among Germanic tribes as early as the first century AD. Whatever its meaning, this ritual dance was practiced for centuries.

Three other designs are very similar to the Sutton Hoo helmet's dance scene. The Valsgärde 7 helmet has an almost identical design. A small piece from Gamla Uppsala is so similar it looks like it came from the same mold.

One of the four Torslunda plates also shows a similar design. This plate is complete. It shows a figure with the same features as in design 1. This suggests the men in the Sutton Hoo design are linked to the cult of Odin. The Torslunda figure is missing an eye. Odin also lost an eye. This supports the idea that the Torslunda figure is Odin, and the Sutton Hoo figures are his followers.

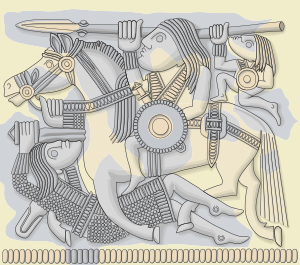

Design 2: Rider and Fallen Warrior

This design is found eight times on the helmet. It might have appeared twelve times originally. The pattern is on the lowest row of the skull cap and in the center of each side. The horse and rider move clockwise around the helmet.

Much of design 2 is missing. So, its reconstruction relies on similar scenes from other places. These are found on the Valsgärde 7 and 8 helmets, the Vendel 1 helmet, and the Pliezhausen bracteate. The Pliezhausen piece is complete and very similar to the Sutton Hoo design.

Design 2 shows a warrior on horseback. He holds a spear over his head. He is trampling an enemy on the ground. The enemy is reaching up. He holds the horse's reins in his left hand. With his right hand, he stabs a sword into the horse's chest. A small human-like figure kneels on the horse's back. This figure is similar to the horseman. It holds the spear with its right hand.

The meaning of design 2 is not fully known. It might come from Roman art, which often showed warriors trampling defeated enemies. This design has been found in England, Sweden, and Germany. This suggests it had a special meaning in Germanic mythology. Roman examples show clear victories. But Germanic versions are more unclear.

The symbolism is not clear. It combines victory and defeat. The rider aims his spear forward, not at the enemy on the ground. The enemy is trampled, but the horse is fatally wounded. A small, possibly divine, figure hovers behind the rider. It seems to guide the spear.

The design might be about fate. The divine figure, possibly Odin, guides the warrior. But it doesn't completely protect him from danger. Even the gods are subject to fate. They can only offer limited help.

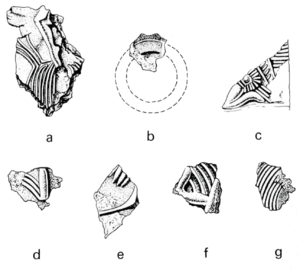

Design 3: Unidentified Scene

Seven small pieces suggest a third scene on the Sutton Hoo helmet. But they are too small and unclear to reconstruct the scene. It might have appeared one to four times. It was likely on the back of the right side of the helmet.

What remains of design 3 might show a "variant rider scene." This could have been used to fix damage to a design 2 panel. This is similar to how a unique design on the Valsgärde 6 helmet was used for repair. For example, one fragment shows parallel raised lines. These suggest the body of a horse. Another fragment seems to be part of a shield rim.

This theory suggests design 3 was a replacement panel. Damage to the back of the helmet supports this idea. The crest is missing a part above the rear dragon head. This head is also mostly missing. This could mean the helmet was damaged and needed repair.

However, this theory doesn't explain why the crest and dragon head weren't repaired. Also, one fragment (c) doesn't fit this idea. It's an edge piece placed on the back right of the helmet. But it doesn't seem to belong with any other fragments or the suggested scene. It might have been a scrap used to fill a gap.

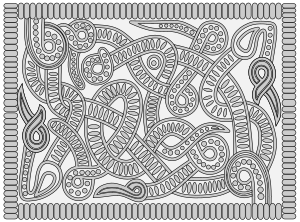

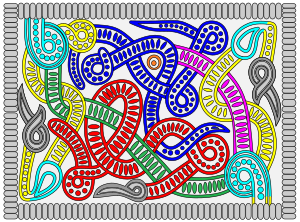

Design 4: Larger Interlace Pattern

|

|

This larger interlace pattern is found on the cheek guards, neck guard, and skull cap. It was possible to reconstruct it completely. Unlike the other designs, both full and partial impressions of design 4 were used. Empty spaces on the skull cap and neck guard allowed for full impressions. On the cheek guards, the designs are partial and sometimes sideways.

Design 4 shows a single animal, or quadruped, in a ribbon style. It has a patterned border on all sides. The animal's head is at the top center. Its eye is made of two circles. The rest of the head is two intertwined ribbons. A third ribbon forms the jaws and mouth.

Another ribbon forms the animal's neck. It starts from the head and goes downwards. It passes under and over a limb ribbon. It ends in a twisted shape, forming the front hip. Two limbs come from this hip. The animal's body is another ribbon connecting the front and rear hips. The rear hip also has two limbs.

This design is an example of what is called "Design II" Germanic animal ornament.

Design 5: Smaller Interlace Pattern

This smaller interlace pattern covered the face mask. It was also used a lot on the neck guard. It filled in empty spaces on the cheek guards. It is an animal design, like the larger interlace. It shows two animals, upside down and reversed. Their heads turn backward towards the center of the panel.

What Was the Helmet Used For?

The Sutton Hoo helmet was both a useful piece of battle gear and a symbol of its owner's power. It would have protected well in battle. As the richest known Anglo-Saxon helmet, it showed its owner's high status.

The helmet is older than the man it was buried with. So, it might have been a family heirloom. It could symbolize important events in its owner's life and death. It might also be an early form of crowns. Crowns appeared in Europe around the twelfth century. They showed a leader's right to rule and their connection to the gods.

We don't know if the helmet was ever worn in battle. But even with its delicate decorations, it would have worked well. It protected the wearer's head completely. Unlike other helmets of its type, it has a face mask, a one-piece cap, and a solid neck guard. The iron and silver crest would have helped deflect blows. Small holes under the nose allowed some air, though it would have been stuffy.

If the helmet was damaged before burial, and if Rædwald owned it, then it was used during his lifetime. This suggests he was a person who saw battle.

Beyond its use in battle, the helmet showed the owner's high status. A simple iron cap would be enough for head protection. But helmets were important symbols in Anglo-Saxon England. This is shown by archaeological finds, poems, and historical records. Helmets are often mentioned in Beowulf, a poem about kings. But only six Anglo-Saxon helmets are known today, despite thousands of graves being excavated.

This scarcity suggests helmets were not buried in large numbers. They showed the importance of those who wore them. The Sutton Hoo helmet was likely about 100 years old when buried. This means it could have been an heirloom, passed down through generations. The shield from the burial might also be an heirloom. Both show clear Swedish influence.

Old poems often mention important heirloom items. In Beowulf, every important sword has a long history. The hero Beowulf gives his follower a gold collar, armor, and a gilded helmet as he dies. Passing down the helmet symbolized passing on titles and power. It was also a final tribute to the buried man.

The Sutton Hoo helmet is much richer than any other known helmet. It comes from a likely royal burial. At that time, kingship was linked to the helmet and sword. Helmets might have become symbols of crowns because rulers wore them often. Early European crowns, like the Holy Crown of Hungary, have a similar basic structure to some helmets. This includes a brow band, a nose-to-nape band, and side bands.

The altered left eyebrow on the Sutton Hoo helmet might suggest a divine right to rule. Or it could show a connection between gods and the leader. The one-eyed look would only be visible in dim light, like in a king's hall.

How Does the Sutton Hoo Helmet Compare to Others?

The Sutton Hoo helmet is unique in many ways. But it is also connected to other Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets. It is one of only six known Anglo-Saxon helmets. The others are from Benty Grange, Coppergate, Wollaston, Shorwell, and Staffordshire. But the Sutton Hoo helmet is more similar to finds in Sweden at Vendel and Valsgärde.

The helmet also has many similarities to those described in the Anglo-Saxon epic poem Beowulf. The Sutton Hoo ship burial has greatly changed how we understand this poem.

Types of Helmets

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a "crested helmet." This is different from the continental spangenhelm and lamellenhelm types. About 50 crested helmets are known. But only about a dozen can be fully rebuilt. Some are so damaged that it's hard to tell if they were helmets. All crested helmets, except for one fragment in Kiev, come from England or Scandinavia.

The Sutton Hoo helmet belongs to the Vendel and Valsgärde group. These helmets came from Roman infantry and cavalry helmets of the fourth and fifth centuries. Helmets were found in graves at Vendel and Valsgärde. The Sutton Hoo helmet has similar designs. But it is "richer and of higher quality" than the Scandinavian ones. Its differences might mean it was made for someone of higher social status. Or it might be closer in time to the Roman helmets it was based on.

| Helmet | Location | Completeness | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sutton Hoo | England: Sutton Hoo, Suffolk | Helmet | ||

| Coppergate | England: York | Helmet | ||

| Benty Grange | England: Derbyshire | Helmet | ||

| Wollaston | England: Wollaston, Northamptonshire | Helmet | ||

| Staffordshire | England: Staffordshire | Helmet | ||

| Guilden Morden | England: Guilden Morden, Cambridgeshire | Fragment (boar) | ||

| Caenby | England: Caenby, Lincolnshire | ? | Fragment (foil) | |

| Rempstone | England: Rempstone, Nottinghamshire | Fragment (crest) | ||

| Asthall | England: Asthall, Oxfordshire | ? | Fragments (foil) | |

| Icklingham | England: Icklingham, Suffolk | Fragment (crest) | ||

| Horncastle | England: Horncastle, Lincolnshire | Fragment (crest) | ||

| Tjele | Denmark: Tjele, Jutland | Fragment (eyebrows/nose) | ||

| Gevninge | Denmark: Gevninge, Lejre, Sjælland | Fragment (eye) | ||

| Gjermundbu | Norway: Norderhov, Buskerud | Helmet | ||

| Øvre Stabu | Norway: Øvre Stabu, Toten, Oppland | ? | Fragment (crest) | |

| By | Norway: By, Løten, Hedmarken | Fragment | ||

| Vestre Englaug | Norway: Vestre Englaug, Løten, Hedmarken | Fragment | ||

| Nes | Norway: Nes, Kvelde, Vestfold | Fragment | ||

| Lackalänga | Sweden | Fragment | ||

| Sweden | Sweden: Unknown location (possibly central) | Fragment (crest) | ||

| Solberga | Sweden: Askeby, Östergötland | |||

| Gunnerstad | Sweden: Gamleby, Småland | Fragments | ||

| Prästgården | Sweden: Prästgården, Timrå, Medelpad | Fragments (crest) | ||

| Vendel I | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vendel X | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Fragments (crest/camail) | ||

| Vendel XI | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Fragments | ||

| Vendel XII | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vendel XIV | Sweden: Vendel, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 5 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 6 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 7 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Valsgärde 8 | Sweden: Valsgärde, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Gamla Uppsala | Sweden: Gamla Uppsala, Uppland | Fragments (foil) | ||

| Ultuna | Sweden: Ultuna, Uppland | Helmet | ||

| Vaksala | Sweden: Vaksala, Uppland | Fragments | ||

| Vallentuna | Sweden: Vallentuna, Uppland | Fragments | ||

| Landshammar | Sweden: Landshammar, Spelvik, Södermanland | Fragments | ||

| Lokrume | Sweden: Lokrume, Gotland | Fragment | ||

| Broe | Sweden: Högbro Broe, Halla, Gotland | Fragments | ||

| Gotland (3) | Sweden: Endrebacke, Endre, Gotland | Fragment | ||

| Gotland (4) | Sweden: Barshaldershed, Grötlingbo, Gotland | Fragment (crest?) | ||

| Hellvi | Sweden: Hellvi, Gotland | Fragments (eyebrow) | ||

| Gotland (6) | Sweden: Unknown, Gotland | Fragment | ||

| Gotland (7) | Sweden: Hallbjens, Lau, Gotland | Fragments | ||

| Gotland (8) | Sweden: Unknown, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | |

| Gotland (9) | Sweden: Grötlingbo(?), Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | |

| Gotland (10) | Sweden: Gudings, Vallstena, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | |

| Gotland (11) | Sweden: Kvie and Allekiva, Endre, Gotland | ? | Fragment (crest) | |

| Uppåkra | Sweden: Uppåkra, Scania | Fragment (eyebrow/boars) | ||

| Desjatinna | Ukraine: Kiev | Fragment (eyebrows/nose) |

Anglo-Saxon Helmets

The Sutton Hoo helmet has only small decorative details and few construction similarities with other known Anglo-Saxon helmets. The Staffordshire helmet might be more closely related. The Sutton Hoo helmet is the only one with a face mask, a fixed neck guard, or a cap made from a single piece of metal.

Its cheek guards and crest are similar to other Anglo-Saxon helmets. But its construction is mostly different. The other helmets' caps were made of at least eight pieces. The Sutton Hoo helmet is unique for its one-piece iron cap.

The Sutton Hoo helmet is the only Anglo-Saxon helmet with a face mask or a fixed neck guard. Other helmets, like Coppergate and Benty Grange, used chainmail or horn for neck protection. They protected the face with elongated nose guards.

The decorations on the Sutton Hoo helmet are very different from other Anglo-Saxon helmets. The Wollaston and Shorwell helmets were made for use, not show. The Shorwell helmet was mostly practical. The Wollaston helmet had only a boar crest and simple lines. Its boar crest is similar to the Benty Grange helmet.

The Coppergate helmet has more similarities. It has a crest and eyebrows. These might imitate the silver wire inlays on the Sutton Hoo helmet. Both helmets also have animal heads at the ends of their eyebrows and crests. These similarities show a set of traditional decorative ideas. They don't mean the helmets are closely related.

The Sutton Hoo helmet looks very rich. It has bronze designs, garnets, gold, and silver wires. This gives it a "rich polychromatic effect." The Staffordshire helmet looks much more similar. It has gilded interlace designs and a possible gold crest. It was also covered in pressblech foils, including a horseman and warrior design.

Scandinavian helmets are built differently from the Sutton Hoo helmet. But they have many similar designs. None of the Scandinavian helmets have a face mask, a solid neck guard, or a one-piece cap. Only two have distinct cheek guards. Their neck guards were usually iron strips or chainmail.

The helmets from Ultuna, Vendel 14, and Valsgärde 5 used iron strips for neck protection. Chainmail was used on helmets from Valsgärde 6, 7, 8, Vendel 1, and 12. Only two helmets had cheek protection other than chainmail or iron strips. The Vendel 14 helmet had cheek guards, but they were different from Sutton Hoo's. The caps on Scandinavian helmets also vary greatly. None are like the Sutton Hoo helmet's cap.

The basic form of helmets from Vendel, Valsgärde, Ultuna, and Broe started with a brow band and nose-to-nape band. The Ultuna helmet had latticed iron strips on its sides. The Valsgärde 8 helmet had six parallel strips on each side. The other four helmets used two side bands and sectional infills.

The decorations and images on the Sutton Hoo and Scandinavian helmets are very similar. This similarity helped rebuild the Sutton Hoo helmet's images. It also led to the idea that the helmet was made in Sweden, not England. Its fancy crest and eyebrows are similar to Scandinavian designs. Some even copy its silver wire inlays.

Garnets decorate the Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde 7 helmets. The pressblech designs on both are common and linked in their meaning. Most Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets have crests. The wire inlays in the Sutton Hoo crest are most similar to "Vendel-type helmet-crests." These imitate wire-inlay patterns in their casting.

The crests from the Vendel 1 and 12 helmets have chevron patterns that copy the Sutton Hoo inlays. The Ultuna helmet and all Valsgärde helmets also have this. The eyebrows of Scandinavian helmets are even more closely linked. Those on the Broe helmet have silver wire inlays. The Lokrume helmet fragment is also inlaid with silver.

Even eyebrows without silver are fancy. The Valsgärde 8, Vendel 1, and Vendel 10 eyebrows have chevron patterns like their crests. The Vendel 14 helmet has parallel lines engraved into its eyebrows. The single eyebrow found at Hellvi is also decorated.

Two Scandinavian helmets, from Valsgärde 7 and Gamla Uppsala, are especially similar to the Sutton Hoo helmet. The Valsgärde 7 crest has a "cast chevron ornament." It is "jeweled" like the Sutton Hoo helmet, but with more garnets. It also has figural and interlace pressblech patterns. These include versions of the two figure designs from the Sutton Hoo helmet.

The Valsgärde 7 version of the dancing warriors design is very similar. It only lacks two crossed spears behind the men. These scenes are so alike that the Sutton Hoo design could only be rebuilt with the Valsgärde 7 design as a guide. The Gamla Uppsala version of this scene is even more similar. It was first thought to be from the same die.

The Valsgärde 7 helmet helps explain the Sutton Hoo helmet's connection to East Scandinavia. Its differences might be because it was found in a "yeoman-farmer's" grave, not a royal one. Royal graves from that time in Sweden haven't been found yet. But their helmets and shields would likely be as high quality as the Sutton Hoo examples. This makes the Gamla Uppsala fragment very interesting. It came from a Swedish royal cremation. The dies seem to have been cut by the same person. So, that helmet might have been similar to the Sutton Hoo helmet.

Roman Helmets

The Sutton Hoo helmet is linked to Roman helmets from the fourth and fifth centuries. Its design, with a crest, solid cap, neck and cheek guards, face mask, and leather lining, is similar to these older helmets. Many Roman helmets have a crest like Sutton Hoo's.

The one-piece cap underneath is unique among Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets. It represents the end of a Greek and Roman technique. This method was used in early Roman Empire helmets. It was likely forgotten around 500 AD. The solid iron cheek guards of the Sutton Hoo helmet also come from the Roman style.

The current reconstruction partly assumes Roman influence for the cheek guards. Roman practices suggested leather hinges were used. The neck guard also likely used leather hinges. Its solid iron construction is very similar to Roman examples.

The Witcham Gravel helmet from the first century AD has a broad and deep neck guard. Solid projecting guards are found on the Deurne and Berkasovo 2 helmets. The Sutton Hoo helmet's face mask is also unique among its contemporaries. But it matches Roman examples. The Ribchester Helmet and the Emesa helmet both have face masks. The Emesa helmet is more similar to Sutton Hoo's. It is attached to the cap by a single hinge.

Finally, the idea of a leather lining in the Sutton Hoo helmet is supported by similar linings in late Roman helmets.

Some decorative parts of the Sutton Hoo helmet also come from Roman practices. These include its white appearance, inlaid garnets, and prominent rivets. Its tinned surface is similar to the Berkasovo 1 and 2 helmets. The Berkasovo 1 and Budapest helmets have precious stones. This might be where the garnets on the Sutton Hoo and Valsgärde 7 helmets came from. The prominent rivets on some crested helmets, like Valsgärde 8 and Sutton Hoo, might have been inspired by Roman helmets.

The Sutton Hoo Helmet and Beowulf

Our understanding of the Sutton Hoo ship burial and the poem Beowulf has been connected since 1939. By the late 1950s, they were almost inseparable. Beowulf helped explain what the seventh-century reality was like. Sutton Hoo gave physical proof to the poem's descriptions.

Helmets are described in great detail in Beowulf. Some specific connections can be made. The boar images, crest, and visor in the poem are similar to the helmet. So is its shiny white and jeweled look. The Sutton Hoo helmet doesn't exactly match any one helmet in Beowulf. But the many similarities show that the poem's descriptions are not just fantasy.

Helmets with boar designs are mentioned five times in Beowulf. They fall into two groups: those with freestanding boars and those without. When Beowulf and his men arrive, their helmets have "boar-shapes flashed above their cheek-guards." These might have been like the ones on the Sutton Hoo helmet. They were at the ends of the eyebrows, looking over the cheek guards.

Beowulf wears a helmet "set around with boar images" before fighting Grendel's mother. It is also called "the white helmet . . . enhanced by treasure." This description could fit the tinned Sutton Hoo helmet.

The other type of boar decoration refers to helmets with a freestanding boar on top of the crest. When King Hrothgar talks about his friend Æschere, he remembers how "our boar-crests had to take a battering." These crests were probably more like those on the Benty Grange and Wollaston helmets. They are also seen in art from that time.

The silver inlays on the Sutton Hoo helmet's crest are also described in Beowulf. The helmet given to Beowulf after he defeats Grendel has similar features. The poem says, "An embossed ridge, a band lapped with wire arched over the helmet." This describes the silver inlays along the Sutton Hoo helmet's crest. Such a crest would protect from a sword blow. Turning the head quickly would make the blow hit the crest, preventing the cap from splitting.

The discovery of the Sutton Hoo helmet helped define the Old English word wala. This word usually means a ridge of land. But in Beowulf, it refers to a helmet's crest. The crest is also described as wirum bewunden, meaning "wire bound." This matches the silver inlays on the Sutton Hoo helmet's crest. The helmet helps us understand the poem better. It shows the close link between the Sutton Hoo grave and Beowulf.

The Sutton Hoo helmet is unique among Anglo-Saxon and East Scandinavian helmets because it has a face mask. This might be because it was part of a royal burial. It is "richer and of higher quality than any other helmet yet found." In Beowulf, a poem about kings, words like "battle-mask" and "war-mask" describe helmets with visors. The term "war-head" fits the Sutton Hoo helmet well. It describes a helmet that covers the whole head, including forehead, eyebrows, eyes, cheeks, nose, mouth, and even a mustache.

How Was the Helmet Found?

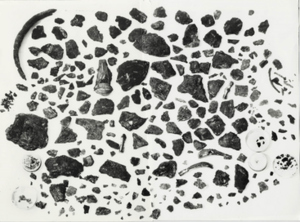

The Sutton Hoo helmet was found over three days in July and August 1939. This was just three weeks before the ship burial excavation ended. It was found in over 500 pieces. These pieces made up less than half of the original helmet's surface.

The archaeologist C. W. Phillips recorded the discovery in his diary. On July 28, 1939, he wrote about finding "the crushed remains of an iron helmet." It had embossed ornament, gold leaf, textiles, a bronze face-piece with a nose, mouth, and mustache, and bronze animal decorations. More fragments were found on July 29 and August 1.

Today, the helmet is one of the most important artifacts found in Britain. But at first, its shattered state made it go unnoticed. No photos were taken of the fragments where they were found. Their exact positions were not recorded. The importance of the discovery was not yet realized. The only record of its location was a circle on the excavation map marked "nucleus of helmet remains."

When reconstruction began years later, it was like a "jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box." And many pieces were missing.

Even before all fragments were dug up, the Daily Mail newspaper wrote about "a gold helmet encrusted with precious stones." A few days later, it described the helmet more accurately. It had "elaborate interlaced ornaments in silver and gold leaf." Even though there was little time to examine the pieces, they were called "elaborate" and "magnificent." It was "crushed and rotted" and "sadly broken." But it was still thought to be "one of the most exciting finds."

Donating the Discovery

At that time, old gold and silver found hidden in the earth belonged to the crown if the owner was unknown. This was called treasure trove. But items with only small amounts of gold or silver, like the Sutton Hoo helmet, were not treasure trove. They belonged to the landowner, Edith Pretty.

An inquest was held on August 14, 1939, for the other items. The jury decided the objects were not treasure trove. So, they belonged to Edith Pretty. The coroner said it was "impossible to be of the opinion that these articles were buried or concealed secretly." This was because of the effort and publicity involved in burying the ship.

Within days, Edith Pretty gave all the finds to the British Museum. Even if the gold and silver items had been declared treasure trove, the helmet would still have belonged to her. So, donating was the main way the museum could get the finds.

Excavations at Sutton Hoo ended on August 24, 1939. All items were shipped out the next day. Nine days later, Britain declared war on Germany. This time allowed fragile items to be cared for. The finds were secured for safekeeping. During World War II, the Sutton Hoo artifacts were stored in a tunnel connecting the Aldwych and Holborn tube stations. In late 1944, preparations began to unpack and restore the finds.

Rebuilding the Helmet: First Attempt

The helmet was first rebuilt by Herbert Maryon between 1945 and 1946. Maryon was a retired sculpture professor. He was an expert on early metalwork. The British Museum hired him in 1944 to restore the Sutton Hoo finds. This included the "real headaches – notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns."

Maryon worked on the Sutton Hoo objects until 1950. He spent six months just on the helmet. It arrived as a corroded mass of fragments. Some were crumbly and covered in sand. Others were hard and partly turned into iron ore. It was like a "jigsaw puzzle without any sort of picture on the lid of the box," and many pieces were missing.

Maryon started by studying each fragment. He traced and detailed them. He sorted them by decoration, markings, and thickness. After a long time, he began rebuilding. He glued pieces together with Durofix. He held them in a box of sand until the glue hardened. Then he placed them on a human-sized plaster head he sculpted. He added layers to account for the original lining.

The skull cap fragments were first stuck to the head with Plasticine. Then strong white plaster was used to permanently attach them. It was mixed with brown color to fill the gaps. The cheek guards, neck guard, and visor fragments were placed on shaped wire mesh covered in plaster. Then they were attached with more plaster and joined to the cap.

Even though it looks different from the current reconstruction, "Much of Maryon's work is valid." The general shape of the helmet became clear. The 1946 reconstruction identified the designs we know today. It also arranged them in panels. Both reconstructions used the same designs for the visor and neck guards. The layout of the cheek guards was also similar.

Re-excavations at Sutton Hoo, 1965–70

Many questions remained after the 1939 excavation. So, a second excavation began in 1965. One goal was to find the ship impression again. Another was to search the old dump sites from 1939 for any missed fragments. The first dig was a "rescue dig" because of the war. This meant fragments might have been accidentally thrown away.

More helmet fragments could help understand the unidentified third design. Or they could support Maryon's idea that 4 inches of the crest were missing. The excavation looked for both new pieces and proof of missing pieces.

Four new helmet fragments were found during this re-excavation. The three 1939 dump sites were found in 1967. They quickly yielded "fragments of helmet and of the large hanging bowl." The finds were so many that one small section of a dump had sixty cauldron fragments. The four helmet pieces came from the second dump. This dump only had items from the ship's burial chamber.

The most important helmet finds were a piece from the cheek guard and the lack of any large crest piece. The cheek guard fragment joined another from 1939. Together, they completed "a hinge plate for one of the moving parts of the helmet." The lack of major crest finds supported the idea that the crest on the first reconstruction was too long.

Rebuilding the Helmet: Current Version

The current reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet was finished in 1971. Nigel Williams worked on it for eighteen months. Williams joined the British Museum in his teens. He was in his mid-20s when he rebuilt the helmet. Maryon, who did the first restoration, was in his 70s and had only one eye.

In 1968, problems with the first reconstruction were still unsolved. So, the museum decided to reexamine the evidence. After months of discussion, they decided to take the helmet apart and rebuild it. The cheek guards, face mask, and neck guard were removed and X-rayed. This showed the wire mesh covered in plaster with fragments on top.

The wire was "rolled back like a carpet." A saw was used to separate each fragment. The remaining plaster was chipped away. The skull cap was cut in half. The central plaster core was removed. The remaining "thin skin of plaster and iron" was separated into individual fragments. This process took four months. It left the helmet in over 500 pieces. Williams found it "terrifying." "One of only two known Anglo-Saxon helmets . . . lay in pieces."

After four months of taking it apart, work began on the new construction. New joins were found by looking at the backs of the fragments. They had a "unique blackened, rippled and bubbly nature." This look is thought to come from a deteriorated leather lining mixed with iron oxide. The wrinkles on the fragments could be matched under a microscope.

The skull cap was built out from the crest. This was helped by finding that only the two grooved strips bordering the crest were gilded. The cheek guards were shaped and made longer. This was done by joining fragments from both sides of the first reconstruction. The exposed jaw areas from the first reconstruction were fixed. An expert suggested the cheek guards should simply switch sides.

After nine months, a "reasonable picture of the original helmet" appeared. The repositioned fragments were placed against a plaster dome. This dome was built up with plasticine to match the helmet's original size. The fragments were held with pins. Then a mixture of jute and adhesive was molded to fill the missing areas. The edges of the fragments were coated with resin. Plaster was spread over the jute to smooth the surface.

The plaster was painted light brown to look like the fragments. This made the fragments stand out. Lines were drawn to show the panel edges. The result was a hollow helmet where the backs of the fragments are still visible. On November 2, 1971, the second and current reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet was put on display.

Cultural Impact of the Helmet

The 1971 reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet was highly praised. In the five decades since, it has become a symbol of the Middle Ages, archaeology, and England. It appears on book covers and has influenced artists and filmmakers. The helmet has become the face of a time once called the "Dark Ages." Now, because of finds like Sutton Hoo, it is known for its sophistication and called the Middle Ages.

The helmet brings to life the descriptions of warriors and mead halls in Beowulf, which were once thought to be imaginary. It represents the Anglo-Saxons in post-Roman Britain. It is an iconic object from a discovery called the "British Tutankhamen." In 2006, it was voted one of the 100 cultural icons of England.

Small Errors in the Current Reconstruction

The current reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet is considered "masterful." But it has "a number of minor problems unsolved" and some small errors. These are mostly in the neck guard. "Very little indeed of the original substance . . . survives that can be positioned with any certainty." Some fragments are only guessed to be in their current spots.

The neck guard has three main problems. Some design 5 fragments are placed too high. This leaves more space below the strips than above them. This space is larger than the design die. The Royal Armouries replica corrected this. It should allow for two full, equal impressions of design 5.

Also, there are not enough fragments to know how many vertical strips of design 5 were used. Seven strips were suggested, but five is also possible. Even if seven is correct, the two strips next to the center one tilt inward. Straightening them would make them fan out naturally. Finally, the neck guard hangs lower than it should. It originally fit inside the cap. This makes the cheek and neck guards misaligned. The Royal Armouries replica corrected this.

Royal Armouries Replica Helmet

In 1973, the Royal Armouries worked with the British Museum to make a copy of the restored Sutton Hoo helmet. The museum provided a blueprint and copies of the decorative parts. The Royal Armouries team completed the task.

There were some differences in how it was built. For example, it had a solid crest and used lead solder. But it stayed very close to the original design. The replica weighed 3.74 kg, which is 1.24 kg heavier than the original.

The finished replica was shown in a dramatic way in September 1973. The lights were dimmed. Nigel Williams walked down the aisle holding a replica of the Sutton Hoo whetstone. Behind him, Rupert Bruce-Mitford wore the Royal Armouries helmet and recited lines from Beowulf.

The Royal Armouries replica helped clarify details of the original helmet. It showed what the helmet looked like when it was new. It could also be worn and tested. The reproduction showed that the neck guard originally fit inside the cap. This allowed it to move more freely. This showed an inaccuracy in the 1971 reconstruction.

The replica also fixed an error in the neck guard's reconstruction. It gave equal length to both the lower and upper parts of design 5. However, it might have added an error by putting a visible border on all four sides of each design 5 impression.

Being able to wear the replica showed several things about the original. It showed how much the wearer could move and see. With enough padding, people with different head sizes could wear it comfortably. The replica also showed that the helmet could be worn in battle. It would make the wearer's voice sound strong.

Most strikingly, the replica showed how the Sutton Hoo helmet originally looked. It appeared as a shining white object, not a rusty brown relic. This helped illustrate the lines in Beowulf that call it "the white helmet . . . enhanced by treasure."

The replica is displayed in the British Museum next to the original helmet in Room 41. It has also been shown around the world.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |