Herbert Maryon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Herbert Maryon

OBE FSA FIIC

|

|

|---|---|

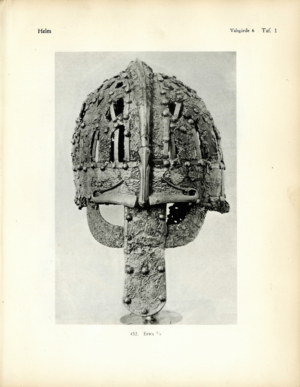

With his reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet, c. 1951. The image to Maryon's left depicts the helmet from Vendel 14; that on his right shows plate 1 from Greta Arwidsson's 1942 work on Valsgärde 6, and depicts the helmet from said grave.

|

|

| Born | 9 March 1874 London, England

|

| Died | 14 July 1965 (aged 91) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Central School of Arts and Crafts |

| Occupation | Sculptor, metalsmith, conservator-restorer |

| Relatives | John, Edith, George, Mildred, Violet (siblings) |

| Signature | |

Herbert James Maryon (9 March 1874 – 14 July 1965) was an English artist who was a sculptor, metalworker, and expert in ancient metal objects. He was also a conservator, which means he helped to repair and preserve old artifacts.

Maryon taught art and sculpture until 1939. Later, from 1944 to 1961, he worked as a conservator at the British Museum. He is most famous for his amazing work on the Sutton Hoo ship-burial treasures. This important work earned him an award called the Order of the British Empire.

Maryon went to several art schools and learned how to work with silver. He also worked in different art workshops. From 1900 to 1904, he was the director of the Keswick School of Industrial Art. There, he designed many beautiful items in the Arts and Crafts style.

Later, he taught at the University of Reading and Durham University. He taught sculpture, metalwork, and how to make models. He also designed memorials, like the University of Reading War Memorial. Maryon wrote two books, including Metalwork and Enamelling, which is still used today! He also went on many archaeological digs. In 1935, he found one of the oldest gold ornaments ever discovered in Britain.

In 1944, Maryon was asked to help restore the treasures from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. He worked on the shield, drinking horns, and the famous Sutton Hoo helmet. His work helped experts understand these ancient objects better. He even came up with the term pattern welding to describe how the Sutton Hoo sword was made stronger and decorated. He left the museum in 1961 and traveled the world, giving talks and studying ancient objects.

Contents

Early Life and Art Training

Herbert James Maryon was born in London on 9 March 1874. He was the third of six children. His father, John Simeon Maryon, was a tailor. His older sister, Louisa Edith, also became a sculptor.

Herbert went to The Lower School of John Lyon. Then, from 1896 to 1900, he studied at several art schools. These included the Polytechnic (now the University of Westminster), The Slade, and Saint Martin's School of Art. He also studied at the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

At these schools, he learned drawing, painting, and enamelling. In 1898, he trained as a silversmith with C. R. Ashbee. He also worked in the workshops of famous artists like Henry Wilson and George Frampton.

A Career in Sculpture and Metalwork

From 1900 to 1939, Maryon taught sculpture, design, and metalwork. During this time, he also created and showed many of his own artworks. In 1899, he displayed a silver cup and a shield at an art exhibition. His work was praised as "agreeable."

Leading the Keswick School of Industrial Art

In March 1900, Maryon became the first director of the Keswick School of Industrial Art. This school was part of the Arts and Crafts movement, which focused on handmade items. The school taught drawing, design, woodcarving, and metalwork. They sold items like trays, frames, and clock-cases.

Maryon's designs helped the school create even more beautiful and varied items. He often focused on the natural look of the metal itself. For example, he designed a bronze plaque for Bernard Gilpin in 1901. This plaque, in St Cuthbert's Church, showed trees with twisted roots. It was inspired by Norse and Celtic styles.

Maryon believed that the purpose of an object should guide its design. He designed many useful items like jugs and teapots. These were often made from a single sheet of metal, showing the hammer marks. The school won many awards for its work.

Maryon had some disagreements with the school's management. Because of this, he left the school at the end of 1904. He then taught metalwork at the Storey Institute in Lancaster for a year.

Teaching at the University of Reading

In 1908, Maryon became a teacher at the University of Reading. He taught sculpture, metalwork, and casting until 1927. In 1912, he published his first book, Metalwork and Enamelling. This book was a practical guide for people working with gold and silver. It was very popular and is still used today!

During World War I, Maryon helped train people to make ammunition. He set up a training center at Reading, especially for women. By 1918, over 400 workers had been trained. After the war, Maryon designed several war memorials. These included the University of Reading War Memorial, which is a clock tower.

Sculpture and Discoveries at Armstrong College

In 1927, Maryon moved to Armstrong College, part of Durham University. He taught sculpture and the history of sculpture until 1939. In 1933, he published his second book, Modern Sculpture. This book looked at modern sculpture from the artists' point of view.

At Durham, Maryon created new artworks. He designed plaques for famous people like George Stephenson. He also created the Statue of Industry for an exhibition in 1929. This statue showed a woman with cherubs. Students at the college famously covered the statue in tar and feathers as a prank!

Maryon also became very interested in archaeology. He led digs along Hadrian's Wall with his students. In 1935, he excavated the Kirkhaugh cairns, which are ancient burial mounds. There, he found one of the oldest gold ornaments ever found in the United Kingdom. It was from the Bronze Age, nearly 4,500 years old!

Maryon retired from Armstrong College in 1939. During World War II, he helped with ammunition work again.

Working at the British Museum

In 1944, the British Museum asked Maryon to come out of retirement. He was hired to help restore the amazing objects found at the Sutton Hoo ship-burial site. This Anglo-Saxon burial was very important. The objects, made of iron, wood, and horn, were very old and fragile.

Maryon's job was to clean, sort, and put together these broken pieces. He worked on the shield, drinking horns, and especially the famous helmet. His practical knowledge of how these objects were made was very helpful. He was made a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1949. In 1956, he received the Order of the British Empire for his work on Sutton Hoo.

Maryon continued to restore other ancient objects at the British Museum. This included Roman artifacts like the Emesa helmet. He finally retired from the museum in 1961, when he was 87 years old.

Reconstructing the Sutton Hoo Helmet

From 1945 to 1946, Maryon spent six months putting together the Sutton Hoo helmet. This helmet was only the second Anglo-Saxon helmet known at the time, and it was very fancy. But it was found in over 500 broken pieces! It was like a giant jigsaw puzzle with many missing parts and no picture to guide him.

Maryon started by carefully tracing each fragment. Then, he made a plaster model of a head. He used this model to help place the helmet pieces. He first used plasticine to hold the pieces, then used white plaster to fix them permanently. He filled the gaps with more plaster. He published his finished reconstruction in 1947.

Maryon's work on the helmet was very important. It was displayed for over twenty years and appeared in many books and TV shows. Later, new techniques and more helmet fragments were found. This showed that Maryon's reconstruction had some small differences from the original. For example, it was a bit smaller than it should have been.

In 1971, a second reconstruction of the helmet was made. But Maryon's first work was still very valuable. It helped experts understand the helmet's general shape and how it was built. His careful work allowed future researchers to learn even more.

After Sutton Hoo

Maryon finished the main Sutton Hoo reconstructions by 1946. He continued to work on other finds until 1950. After that, he focused on other projects at the British Museum. He also traveled, giving talks in places like Toronto and Philadelphia.

In 1955, Maryon restored the Roman Emesa helmet. This helmet had been found in Syria and was very damaged. Maryon also worked with another expert, Harold Plenderleith, on other projects. They wrote a chapter on metalwork for a book series called History of Technology.

Later Years and Travels

Maryon officially left the British Museum in 1961. He gave some of his own artworks to the museum. He then planned a trip around the world. In late 1961, he left for Fremantle, Australia. There, he visited his brother George, whom he hadn't seen in 60 years.

From Australia, Maryon traveled to San Francisco. He traveled by bus and stayed in cheap hotels. Even at 89 years old, he was full of energy! He visited many museums and studied Chinese magic mirrors. He gave guest lectures in places like the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His trip ended in Toronto, Canada, where his son John lived.

Personal Life

In July 1903, Maryon married Annie Elizabeth Stones. They had a daughter named Kathleen. Annie died in 1908. In September 1920, Maryon married Muriel Dore Wood. They had two children, John and Margaret.

Herbert Maryon lived most of his life in London. He passed away on 14 July 1965, in Edinburgh, Scotland. He was 91 years old.

Works by Maryon

Books

Articles

-

- Republication of passages from

-

- Republication of

Other

-

- Excerpt of a lecture.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |