George Stephenson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

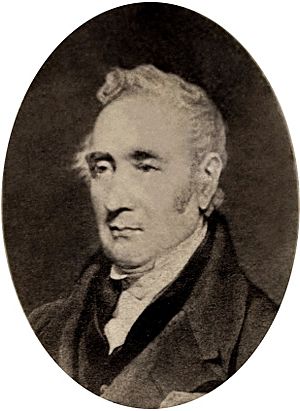

George Stephenson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 9 June 1781 Wylam, Northumberland, England

|

| Died | 12 August 1848 (aged 67) Tapton House, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, England

|

| Resting place | Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Frances Henderson (1802–1806) Elizabeth Hindmarsh (1820–1845) Ellen Gregory (1848) |

| Children | Robert Stephenson Frances Stephenson (died in infancy) |

George Stephenson (born June 9, 1781 – died August 12, 1848) was a brilliant British engineer. He is often called the "Father of Railways." People during the Victorian era saw him as a great example of hard work and a desire to make things better.

Stephenson's railway track width, known as "Stephenson gauge," became the basis for the standard track width used by most railways around the world. This width is about 4 feet 8½ inches (1.435 meters).

Rail transport, which Stephenson helped to create, was one of the most important inventions of the 1800s. It was a key part of the Industrial Revolution. George and his son Robert had a company called Robert Stephenson and Company. Their locomotive, the Locomotion No. 1, was the first steam engine to carry passengers on a public railway line. This happened on the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825. George also built the first public railway line between two cities in the world that used locomotives. This was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in 1830.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

George Stephenson was born on July 9, 1781, in Wylam, Northumberland, England. This village is about 9 miles (15 km) west of Newcastle upon Tyne. He was the second child of Robert and Mabel Stephenson. Neither of his parents could read or write. His father worked as a fireman for a coal mine's pumping engine. He earned very little money, so George could not go to school.

At 17, Stephenson became an engineman at a nearby mine. George understood how important education was. He paid to study at night school to learn reading, writing, and math. He could not read or write until he was 18 years old.

In 1801, he started working as a 'brakesman' at another coal mine. A brakesman controlled the winding gear that lifted things out of the pit. In 1802, he married Frances Henderson. They moved to Willington Quay and lived in one room of a small house. George made extra money by making shoes and fixing clocks.

Their first child, Robert, was born in 1803. In 1804, they moved to Dial Cottage near Killingworth. George worked there as a brakesman. Their second child, a daughter named Frances, was born in July 1805. Sadly, she died after only three weeks.

In 1806, George's wife Frances died from a serious illness. She was buried in the same churchyard as their daughter. George then went to work in Scotland for a few months. He left Robert with a local woman. He returned because his father was blinded in a mining accident. His unmarried sister, Eleanor, moved in to help care for Robert.

In 1811, a pumping engine at High Pit, Killingworth, was not working well. Stephenson offered to fix it. He did such a good job that he was promoted. He became the enginewright for the Killingworth collieries. This meant he was in charge of keeping all the mine engines working. He became an expert in steam-powered machines.

Important Inventions

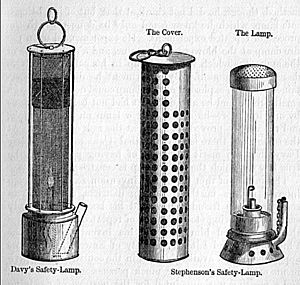

The Safety Lamp

In 1815, George Stephenson knew that open flames in mines often caused dangerous explosions. These explosions happened because of a flammable gas called firedamp. He began to experiment with a safety lamp that could burn in gassy air without causing an explosion. At the same time, a famous scientist named Humphry Davy was also working on this problem.

Even though Stephenson did not have much scientific training, he designed a lamp. Air entered his lamp through tiny holes. The flame could not pass through these holes. This made the lamp safe.

Stephenson showed his lamp to two witnesses. He took it into Killingworth Colliery and held it near a crack where firedamp was escaping. The lamp worked safely. Davy's lamp used a screen of gauze around the flame. Stephenson's lamp had a perforated plate inside a glass cylinder.

Davy was given money for his invention. Stephenson was accused of stealing Davy's idea. People thought Stephenson, an uneducated man, could not have invented such a device on his own. Stephenson spoke with a strong local accent, which made him seem less important to people in power. Because of this, he made sure his son Robert went to a private school. Robert learned to speak in a more formal way.

A local group supported Stephenson. They proved he had invented his "Geordie Lamp" on his own. They gave him £1,000. Davy and his supporters refused to believe Stephenson. Later, in 1833, a committee in the British Parliament agreed that Stephenson had an equal claim to inventing the safety lamp.

The Stephenson lamp was mostly used in North East England. The Davy lamp was used everywhere else. This experience made Stephenson distrust experts from London who relied only on theories. Some people believe that the name "Geordie" for people from North East England came from Stephenson's "Geordie Lamp."

Locomotives

Richard Trevithick is known for designing the first realistic steam locomotive in 1802. He later built an engine for a mine owner in Tyneside. This inspired several local men, including Stephenson, to design their own engines.

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814. It was called Blücher. It was made to pull coal on the Killingworth wagonway. It could pull 30 tons of coal up a hill at 4 miles per hour (6.4 km/h). This was the first successful locomotive that used its flanged wheels to grip the rails for traction.

Stephenson built about 16 locomotives at Killingworth. Most were for use at Killingworth or the Hetton colliery railway. He also improved the design of cast-iron rails to make them stronger. He later used wrought-iron rails for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. These rails were stronger and less likely to break.

Hetton Railway

In 1820, Stephenson was hired to build the 8-mile (13 km) Hetton colliery railway. He used a mix of gravity for downhill parts and locomotives for flat or uphill parts. This railway, which opened in 1822, was the first to use no animal power. It used a track width of 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 meters).

The First Railways

Stockton and Darlington Railway

In 1821, a law was passed to build the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR). This 25-mile (40 km) railway connected coal mines near Bishop Auckland to the River Tees at Stockton. It passed through Darlington. The first plan was to use horses to pull coal carts. But after a company director, Edward Pease, met Stephenson, they decided to use steam locomotives. Stephenson surveyed the route in 1821, and construction began that year with help from his 18-year-old son, Robert.

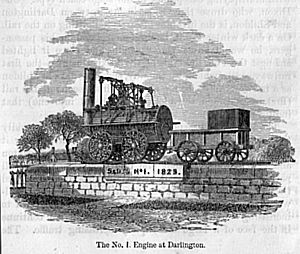

A company was needed to build the locomotives. Pease and Stephenson started a company in Newcastle called Robert Stephenson and Company. George's son Robert was the managing director. In September 1825, their factory finished the first locomotive for the railway. It was first called Active, but then renamed Locomotion. Three more engines followed.

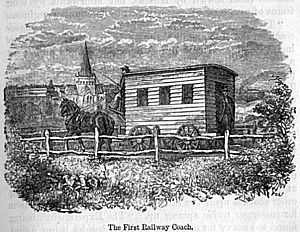

The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825. Stephenson drove Locomotion. It pulled an 80-ton load of coal and flour 9 miles (14 km) in two hours. It reached a speed of 24 miles per hour (39 km/h) on one part of the track. The first passenger car, Experiment, was attached. It carried important people on the opening journey. This was the first time passengers rode on a steam locomotive railway.

The track width Stephenson chose for this line was 4 feet 8½ inches (1.435 meters). This width later became the standard for railways around the world.

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Stephenson learned that even a small uphill slope could greatly reduce a locomotive's power. He believed railways should be as flat as possible. He used this idea when building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR). He made many difficult cuts through hills, built embankments, and stone bridges to keep the route level.

Building the L&MR was challenging. One big problem was crossing Chat Moss, a very deep peat bog. Stephenson solved this by floating the line across it. He laid a foundation of heather and branches. The weight of the trains then pressed these together, with stones on top. This method was similar to what John Metcalf used for roads across marshes.

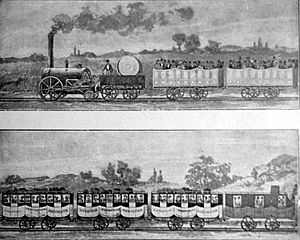

As the L&MR was almost finished in 1829, its directors held a competition. They wanted to decide who would build the locomotives. The Rainhill Trials took place in October 1829. Stephenson's entry was Rocket. Its amazing performance made it famous. George's son Robert designed many of the details for Rocket.

The opening ceremony of the L&MR was on September 15, 1830. Many important people attended, including the Prime Minister. Eight trains left Liverpool in a procession. George Stephenson drove the lead train, Northumbrian. Sadly, the day was marked by tragedy. William Huskisson, a Member of Parliament, was hit by Rocket and died from his injuries. Despite this, the railway was a huge success. Stephenson became very famous and was asked to be the chief engineer for many other railways.

Stephenson's Skew Arch Bridge

In 1830, a special bridge called a skew bridge opened in Rainhill. It crossed the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This was the first bridge to cross any railway at an angle. To build it, the bricks forming the arch had to be laid at an angle. This creates a spiral pattern in the masonry. This technique makes the arch stronger to handle the angled supports.

This bridge is still used today at Rainhill railway station. It carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). It is considered a historic building.

Later Life and Legacy

Life at Alton Grange

George Stephenson moved to Alton Grange in Leicestershire in 1830. He was there to advise on the Leicester and Swannington Railway. This line was mainly planned to carry coal to Leicester. Stephenson invested his own money in the project. His son Robert became the chief engineer. The first part of the line opened in 1832.

Stephenson also bought the Snibston estate. It was next to the proposed railway route and had valuable coal. He knew that Leicester needed coal, which was then brought by canal from far away. With the new railway, he could bring coal directly to Leicester. His coal mine was very successful. It delivered the first train cars of coal to Leicester, which greatly lowered the price of coal for the city.

Stephenson stayed at Alton Grange until 1838. He then moved to Tapton House in Derbyshire.

Later Career

The next ten years were very busy for Stephenson. Many people building railways asked for his help. Early American railway builders came to Newcastle to learn from him. Stephenson believed railways should be as flat as possible, even if it meant longer routes. This made his projects more expensive than some others.

Stephenson worked on many important railway lines. These included the North Midland Railway from Derby to Leeds, the York and North Midland Railway from Normanton to York, and the Manchester and Leeds Railway.

By 1847, Stephenson was semi-retired. He was the first president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers when it was formed. He spent his later years looking after his mining interests in Derbyshire.

Personal Life

George Stephenson married Frances Henderson in 1802. They had two children, Robert (born 1803) and Fanny (born 1805). Sadly, Fanny died when she was only a few months old. George's wife, Frances, died the next year. While George worked in Scotland, his son Robert was cared for by neighbors and then by George's sister, Eleanor.

In 1820, George married Elizabeth (Betty) Hindmarsh. This marriage seemed happy, but they had no children. Betty died in 1845.

In 1848, George married for a third time to Ellen Gregory. Seven months later, George became ill and died at the age of 67. He was buried at Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield, next to his second wife.

Stephenson was known as a generous man. He helped the families of workers who died while working for him. He also loved gardening. At Tapton House, he grew exotic fruits and vegetables in his greenhouses. He even had a friendly competition with Joseph Paxton, a famous gardener.

Descendants

George Stephenson had two children. His son Robert was born in 1803. Robert became a major railway engineer, just like his father. He worked on projects around the world, including the railway in Egypt that connected to the Suez Canal. Robert had no children. George's daughter died as a baby. Some of George Stephenson's relatives still live in Wylam, his birthplace.

Legacy

Influence

Britain led the world in developing railways. Railways helped the Industrial Revolution by making it easier to move raw materials and finished goods. George Stephenson's work on the Stockton and Darlington Railway and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway paved the way for other railway engineers. These included his son Robert, his assistant Joseph Locke, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Stephenson was smart enough to realize that all the individual railway lines would eventually connect. He knew they would need to use the same track width. The standard gauge used in much of the world today is thanks to him.

In 2002, Stephenson was named among the "100 Greatest Britons" in a BBC television show. He was ranked 65th. His story was very popular. From 1990 to 2003, Stephenson's picture was on the back of the British five-pound note. The Stephenson Railway Museum in North Shields is named after George and Robert Stephenson.

Memorials

George Stephenson's Birthplace is a historic house museum in Wylam. It is run by the National Trust. Dial Cottage at West Moor, where he lived from 1804, still stands.

The Chesterfield Museum has a collection of Stephenson's items. This includes special glass tubes he invented for growing straight cucumbers! The museum is in the Stephenson Memorial Hall, near his last home, Tapton House. In Liverpool, where he lived, there is a plaque on his former home.

George Stephenson College at Durham University is named after him. Also, George Stephenson High School in Killingworth and the Stephenson Railway Museum are named in his honor. His last home, Tapton House, is now part of Chesterfield College.

A bronze statue of Stephenson was put up at Chesterfield railway station in 2005. A working replica of the Rocket was also shown there. Another statue of him stands in Newcastle.

His profile is carved into the facade of Lisbon's Victorian railway station. There is also a street named Via Giorgio Stephenson in Milan, Italy.

See also

In Spanish: George Stephenson para niños

In Spanish: George Stephenson para niños

- History of Science and Technology

- Industrial Revolution

- Train

- Robert Stephenson

- Robert Stephenson and Company

Biographical works

- Smiles, Samuel (1857). The Life of George Stephenson. London. https://archive.org/details/pli.kerala.rare.4329.

"Stephenson, George". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh) 25. (1911). Cambridge University Press.

"Stephenson, George". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh) 25. (1911). Cambridge University Press. - Rolt, L.T.C. (1960). George and Robert Stephenson: The Railway Revolution. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-007646-2.

- Davies, Hunter (2004). George Stephenson: The Remarkable Life of the Founder of Railways. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3795-5.

- Ross, David (2010). George and Robert Stephenson: A Passion for Success. Stroud: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5277-7.

Ruth Maxwell M.A. George Stephenson George Harrap & Company LTD., London, 1920. Heroes of All Time series.[[Category:P

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |